Wien's displacement law

Wien's displacement law states that the wavelength distribution of thermal radiation from a black body at any temperature has essentially the same shape as the distribution at any other temperature, except that each wavelength is displaced on the graph. Apart from an overall T3 multiplicative factor, the average thermal energy in each mode with frequency ν only depends on the ratio ν/T. Restated in terms of the wavelength λ = c/ν, the distributions at corresponding wavelengths are related, where corresponding wavelengths are at locations proportional to 1/T. Blackbody radiation approximates to Wien's law at high frequency.

From this general law, it follows that there is an inverse relationship between the wavelength of the peak of the emission of a black body and its temperature when expressed as a function of wavelength, and this less powerful consequence is often also called Wien's displacement law in many textbooks.

where λmax is the peak wavelength, T is the absolute temperature of the black body, and b is a constant of proportionality called Wien's displacement constant, equal to 2.8977721(26)×10−3 m K.[1]

For wavelengths near the visible spectrum, it is often more convenient to use the nanometer in place of the meter as the unit of measure.

In the field of plasma physics temperatures are often measured in units of electron volts and the proportionality constant becomes b = 249.71066 nm·eV.

Explanation and familiar approximate applications

The law is named for Wilhelm Wien, who derived it in 1893 based on a thermodynamic argument. Wien considered adiabatic, or slow, expansion of a cavity containing waves of light in thermal equilibrium. He showed that under slow expansion or contraction, the energy of light reflecting off the walls changes in exactly the same way as the frequency. A general principle of thermodynamics is that a thermal equilibrium state, when expanded very slowly stays in thermal equilibrium. The adiabatic principle allowed Wien to conclude that for each mode, the adiabatic invariant energy/frequency is only a function of the other adiabatic invariant, the frequency/temperature.

Max Planck reinterpreted a constant closely related to Wien's constant b as a new constant of nature, now called Planck's constant, which relates the frequency of light to the energy of a light quantum.

Wien's displacement law implies that the hotter an object is, the shorter the wavelength at which it will emit most of its radiation, and also that the wavelength for maximal or peak radiation power is found by dividing Wien's constant by the temperature in kelvins.

Examples

- Light from the Sun: The effective temperature of the Sun is 5778 K. Using Wien's law, it is often concluded that this corresponds to a peak emission at a wavelength of 2.90 million nm K/ 5778 K = 502 nm. This is the wavelength of green light, and it is near the peak sensitivity of the human eye. [2] [3] The claim is then made that the human eye evolved to be most sensitive to the peak emission from the Sun. In fact, Wien's law says that the Sun's peak emission per unit wavelength is at 502 nm. When the spectrum is reckoned per frequency interval, the Sun's peak emission appears at a frequency of 3.43 x 1014 Hz; this means that the peak emission per unit frequency is at 3.43 x 1014 Hz, which corresponds to a wavelength of 883 nm and is well into the infrared. That is, the apparent "peak" of the spectrum is significantly affected by the bookkeeping convention by which one describes the spectrum. (Evolution of the eye was more likely influenced by the spectral absorption properties of water than by the Sun's spectrum.) [4] [5]

There are many familiar situations to which Wien's Law may be applied:

- Light from incandescent bulbs and fires: A lightbulb has a glowing wire with a somewhat lower temperature, resulting in yellow light, and something that is "red hot" is again a little less hot. It is easy to calculate that a wood fire at 1500 K puts out peak radiation at 3 million nm K /1500 K = 2000 nm = 20,000 Å. This is far more energy in the infrared than in the visible band, which ends about 7500 Å.

- Radiation from mammals and the living human body: Mammals at roughly 300 K emit peak radiation at 3 thousand μm K / 300 K = 10 μm, in the far infrared. This is therefore the range of infrared wavelengths that pit viper snakes and passive IR cameras must sense.

Frequency-dependent formulation

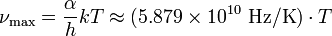

In terms of frequency  (in hertz), Wien's displacement law becomes

(in hertz), Wien's displacement law becomes

where α ≈ 2.821439... is a constant resulting from the numerical solution of the maximization equation, k is the Boltzmann constant, h is the Planck constant, and T is the temperature (in kelvins).

Because the spectrum from Planck's law of black body radiation takes a different shape in the frequency domain from that of the wavelength domain, the frequency location of the peak emission does not correspond to the peak wavelength using the simple relationship between frequency, wavelength, and the speed of light. In other words, the peak wavelength and the peak frequency do not correspond.

Derivation from Planck's Law

Wilhelm Wien first derived this law in 1893 by applying the laws of thermodynamics to electromagnetic radiation.[6] A modern variant of Wien's derivation can be found in the textbook by Wannier.[7]

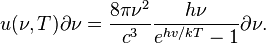

Planck's law for the spectrum of black body radiation may be used to find the actual constant in the peak displacement law. Specifically, the spectral energy density (that is, the energy density per unit frequency) is

However the frequency is a non-linear function of wavelength

⇒

⇒

This allows to present the energy density depending on the wavelength

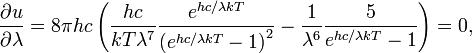

Differentiating u(λ,T) with respect to λ and setting the derivative equal to zero gives

which can be simplified to give

By defining the dimensionless quantity

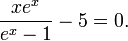

then the equation becomes

The numerical solution to this equation is[note 1]

Solving for the wavelength λ in units of nanometers, and using kelvins for the temperature yields:

The frequency form of Wien's displacement law is derived using similar methods, but starting with Planck's law in terms of frequency instead of wavelength. The effective result is to substitute 3 for 5 in the equation for the peak wavelength. This is solved giving x = 2.82143937212...

Using the value 4 in this equation (midway between 3 and 5) yields a "compromise" wavelength-frequency-neutral peak, which is given for x = 3.92069039487....

See also

Notes

- ↑ The equation

cannot be solved in terms of elementary functions. It can be solved in terms of Lambert's product log function but an exact solution is not important in this derivation.

cannot be solved in terms of elementary functions. It can be solved in terms of Lambert's product log function but an exact solution is not important in this derivation.

References

- ↑ "CODATA Value: Wien wavelength displacement law constant". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. US National Institute of Standards and Technology. June 2011. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ↑ Walker, J. Fundamentals of Physics, 8th ed., John Wiley and Sons, 2008, p. 891. ISBN 9780471758013.

- ↑ Feynman, R; Leighton, R; Sands,M. The Feynman Lectures on Physics, vol. 1, pp. 35-2 – 35-3. ISBN 0201510030.

- ↑ Soffer, B. H.; Lynch, D. K. (1999). "Some paradoxes, errors, and resolutions concerning the spectral optimization of human vision". American Journal of Physics 67 (11): 946–953.

- ↑ Heald, M. A. (2003). "Where is the 'Wien peak'?". American Journal of Physics 71 (12): 1322–1323.

- ↑ Mehra, J.; Rechenberg, H. (1982). The Historical Development of Quantum Theory. New York: Springer-Verlag. Chapter 1. ISBN 978-0-387-90642-3.

- ↑ Wannier, G. H. (1987) [1966]. Statistical Physics. Dover Publications. Chapter 10.2. ISBN 978-0-486-65401-0. OCLC 15520414.

Further reading

- Soffer, B. H.; Lynch, D. K. (1999). "Some paradoxes, errors, and resolutions concerning the spectral optimization of human vision". American Journal of Physics 67 (11): 946–953. Bibcode:1999AmJPh..67..946S. doi:10.1119/1.19170.

- Heald, M. A. (2003). "Where is the 'Wien peak'?". American Journal of Physics 71 (12): 1322–1323. Bibcode:2003AmJPh..71.1322H. doi:10.1119/1.1604387.