Palace of Whitehall

Coordinates: 51°30′16″N 0°7′32″W / 51.50444°N 0.12556°W

The Palace of Whitehall (or Palace of White Hall) was the main residence of the English monarchs in London from 1530 until 1698 when all except Inigo Jones's 1622 Banqueting House was destroyed by fire. Before the fire it had grown to be the largest palace in Europe, with over 1,500 rooms, overtaking the Vatican and Versailles.[3] The palace gives its name, Whitehall, to the road on which many of the current administrative buildings of the UK government are situated, and hence metonymically to the central government itself.

Location

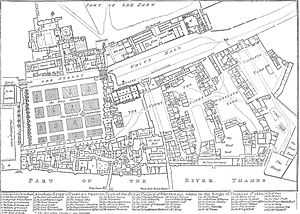

At its most expansive, the palace extended over much of the area currently bordered by Northumberland Avenue in the north; to Downing Street and nearly to Derby Gate in the south; and from roughly the elevations of the current buildings facing Horse Guards Road in the west, to the then banks of the river Thames in the east (the construction of Victoria Embankment has since reclaimed more land from the Thames)—a total of about 23 acres (93,000 m2).

History

By the 13th century, the Palace of Westminster had become the centre of government in England, and had been the main London residence of the king since 1049. The surrounding area became a very popular, and expensive, location. The archbishop of York Walter de Grey bought a property in the area as his London residence soon after 1240, calling it York Place.

Edward I of England stayed at the property on several occasions while work was carried out at Westminster, and enlarged the building to accommodate his entourage. York Place was rebuilt during the 15th century and expanded so much by Cardinal Wolsey that it was rivalled by only Lambeth Palace as the greatest house in London, the king's London palaces included. Consequently, when King Henry VIII removed the cardinal from power in 1530, he acquired York Place to replace Westminster as his main London residence. He inspected its treasures in the company of Anne Boleyn. The phrase Whitehall or White Hall is first recorded in 1532; it had its origins in the white stone used for the buildings.

Henry VIII subsequently redesigned York Place, and further extended and rebuilt the palace during his lifetime. Inspired by Richmond Palace, he also included a recreation centre with a bowling green, indoor tennis court, a pit for cock fighting (now the site of the Cabinet Office, 70 Whitehall) and a tiltyard for jousting (now the site of Horse Guards Parade). It is estimated that over £30,000 (approaching £11m in 2007 values)[4] were spent during the 1540s, 50% more than the construction of the entire Bridewell Palace. Henry VIII married two of his wives at the palace—Anne Boleyn in 1533 and Jane Seymour in 1536. It was also at the palace that the King died in January 1547. In 1611 the palace hosted the first known performance of William Shakespeare's play The Tempest.

James I made a few significant changes to the buildings, notably the construction in 1622 of a new Banqueting House built to a design by Inigo Jones to replace a series of previous banqueting houses dating from the time of Elizabeth I. Its decoration was finished in 1634 with the completion of a ceiling by Sir Peter Paul Rubens, commissioned by Charles I (who was to be executed in front of the building in 1649). By 1650, the Palace was the largest complex of secular buildings in England, with over 1,500 rooms. The layout was extremely irregular, and the constituent parts were of many different sizes and in several different architectural styles. The palace looked more like a small town than a single building.[5]

Charles II commissioned minor works. Like his father, he died at the Palace—though from a stroke, not execution. James II ordered various changes by Sir Christopher Wren, including a new chapel finished in 1687, rebuilding of the queen's apartments (c. 1688[citation needed]), and the queen's private lodgings (1689).

Demise

By 1691, the palace had become the largest and most complex in Europe. On 10 April, a fire broke out in the much-renovated apartment of the Duchess of Portsmouth that damaged the older palace structures, though apparently not the state apartments.[6] This actually gave a greater cohesiveness to the remaining complex. At the end of 1694 Mary II died in Kensington Palace of smallpox, and on the 24th of the following January lay in state at Whitehall; William and Mary had avoided Whitehall in favour of their palace at Kensington. However a second fire on 4 January 1698 destroyed most of the remaining residential and government buildings;[7] the diarist John Evelyn noted succinctly the next day: "Whitehall burnt! nothing but walls and ruins left."[8] Beside the Banqueting House, some buildings survived in Scotland Yard and some facing the Park, along with the so-called Holbein Gate, eventually demolished in 1769. Despite some rebuilding, financial constraints prevented large scale reconstruction. In the second half of the 18th century, much of the site was leased for the construction of town houses.

During the fire many works of art were destroyed, probably including Michelangelo's Cupid, a famous sculpture bought as part of the Gonzaga collections in the seventeenth century. Also lost were Hans Holbein the Younger's iconic Portrait of Henry VIII and Gian Lorenzo Bernini's marble portrait bust of king Charles I.

Present day

The Banqueting House is the only integral building of the complex now standing, although it has been somewhat modified. Various other parts of the old palace still exist, often incorporated into new buildings in the Whitehall government complex. These include a tower and other parts of the former covered tennis courts from the time of Henry VIII, built into the Old Treasury and Cabinet Office at 70 Whitehall.[9]

Beginning in 1938, the east side of the site was redeveloped with the building now housing the Ministry of Defence. An undercroft from Wolsey's Great Chamber, now known as Henry VIII's Wine Cellar, a fine example of a Tudor brick-vaulted roof some 70 feet (21.3 m) long and 30 feet (9.1 m) wide, was found to interfere not just with the plan for the new building but also with the proposed route for Horse Guards Avenue. Following a request from Queen Mary in 1938 and a promise in Parliament, provision was made for the preservation of the cellar. Accordingly it was encased in steel and concrete and relocated nine feet to the west and nearly 19 feet (5.8 m) deeper in 1949, when building was resumed at the site after World War II. This was carried out without any significant damage to the structure and it now rests within the basement of the building.[10]

A number of marble carvings from the former chapel at Whitehall (which was built for James II) can now be seen in St Andrew's Church, Burnham-on-Sea, in Somerset, to where they were moved in 1820 after having originally been removed to Westminster Abbey in 1706.

See also

- List of demolished buildings and structures in London

- List of English/UK palaces

- Palace of Westminster – Main London royal residence from 1049 until 1530

- Kensington Palace – The main London royal residence used by some monarchs between 1689 and 1760

- St. James's Palace – Main London royal residence from 1702 until 1837, continues today as the official palace of the monarchy (Court of St. James)

- Buckingham Palace – Main London royal residence since 1837

References

- ↑ Approximate date provided by the Government Art Collection

- ↑ The buildings are identified in a pictorial map of 1682 by William Morgan. Reproduced in Barker, Felix; Jackson, Peter (1990). The History of London in Maps. London: Barrie and Jenkins. pp. 42–43. ISBN 0-7126-3650-1. ; the so-called "Holbein Gate" as it was known in the 18th century, though any connection with Hans Holbein was fanciful (John Summerson, Architecture in Britain 1530–1830, 9th ed. 1993: 32) survived the fire and was demolished in 1769.

- ↑ "Whitehall". BBC. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ Measuring Worth calculator

- ↑ "Nothing but a heap of Houses, erected at divers times, and of different Models, which they made Contiguous in the best Manner they could for the Residence of the Court", noted the French visitor Samuel de Sorbière about 1665.

- ↑ "Fire in Whitehall ends an age of palaces". London Online. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ↑ Thurley, Simon (1999). Whitehall Palace: an architectural history of the royal apartments, 1240–1698. Yale University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-300-07639-4. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Evelyn, John (1906). The diary of John Evelyn. Macmillan and co., limited. p. 334. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Duncan, Andrew (2006). "Cabinet Office". Secret London (5 ed.). London: New Holland. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-84537-305-4.

- ↑ The Old War Office Building; a History

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palace of Whitehall. |

- Information about the Palace of Whitehall from the Survey of London: History; Buildings; Banqueting House

- Palace of Whitehall timeline

- Enlarged 1680 plan of Whitehall, showing the location of the tennis courts, cockpit, tiltyard on the St. James's Park side, and the configuration of buildings on the river side

- View of Whitehall in 1669, showing the Banqueting House and Holbein Gateway

- A historical record of Whitehall Palace

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||