Western world

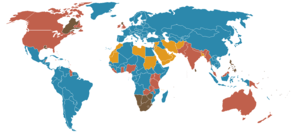

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident (from Latin: occidens "sunset, West"; as contrasted with the Orient), is a term referring to different nations depending on the context. There are many accepted definitions about what all they have in common.[1]

The concept of the Western part of the earth has its roots in Greco-Roman civilization in Europe, and the advent of Christianity. In the modern era, Western culture has been heavily influenced by the traditions of the Renaissance, Protestant Reformation, Age of Enlightenment—and shaped by the expansive colonialism of the 15th-20th centuries. Before the Cold War era, the traditional Western viewpoint identified Western Civilization with the Western Christian (Catholic-Protestant) countries and culture.[2] Its political usage was temporarily changed by the antagonism during the Cold War in the mid-to-late 20th Century (1947–1991).

The term originally had a literal geographic meaning. It contrasted Europe with the linked cultures and civilizations of the Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia and remote Far East, which early-modern Europeans saw as the East. Today, this has little geographic relevance, since the United States and Canada are in the Americas, Russia expands to Northern Asia and Australia and New Zealand are part of Oceania.

In the contemporary cultural meaning, the phrase "Western world" includes Europe, as well as many countries of European colonial origin with substantial European ancestral populations in the Americas and Oceania.[3][4][5]

Introduction

Western culture originated in the Mediterranean basin and its vicinity; Greece and Rome are often cited as its originators. Over time, their associated empires grew first to the east and west to include the rest of the Mediterraneanan and Black Sea coastal areas, conquering, absorbing, and being influenced by many older great civilizations of the ancient Near East (i.e., Phoenicia, Phoenician rooted Carthage, Mesopotamia and also Egypt). Later, they expanded to the north of the Mediterranean Sea to include Western, Central and Southeastern Europe. Christianization of Bulgaria (9th century), Christianization of Kievan Rus' (Russia, Ukraine, Belarus; 10th century), Christianisation of Scandinavia (12th century) and Christianization of Lithuania (14th century) brought the rest of European states to the Western civilisation.

Historians, such as Carroll Quigley in The Evolution of Civilizations,[6] contend that Western civilization was born around 500 AD, after the total collapse of the Western Roman Empire, leaving a vacuum for new ideas to flourish that were impossible in Classical societies. In either view, between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Renaissance, the West (or those regions that would later become the heartland of the culturally "western sphere") experienced a period of first, considerable decline,[7] and then readaptation, reorientation and considerable renewed material, technological and political development. This whole period of roughly a millennium is known as the Middle Ages, its early part forming the "Dark Ages", designations that were created during the Renaissance and reflect the perspective on history, and the self-image, of the latter period.

The knowledge of the ancient Western world was partly preserved during this period due to the survival of the Eastern Roman Empire and the institutions of the Catholic Church; it was also greatly expanded by the Arab importation[8][9] of both the Ancient Greco-Roman and new technology through Arabs from India and China to Europe.[10][11] Since the Renaissance, the West evolved beyond the influence of the ancient Greeks and Romans and the Islamic world due to the Commercial,[12] Scientific,[13] and Industrial Revolutions,[14] and the expansion of the peoples of Western and Central European empires, and particularly the globe-spanning empires of the 18th and 19th centuries. Numerous times, this expansion was accompanied by Christian missionaries, who attempted to proselytize Christianity.

Generally speaking, the current consensus would locate the West, at the very least, in the cultures and peoples of Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and parts of Latin America. There is debate among some as to whether Latin America is in a category of its own.[2][15][16] Also, there is debate among some as to whether Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) [17][18][19] is in a category of its own. An argument supporting Central and Eastern Europe being a part of the West is that Central European, Southeastern European and Baltic countries such as Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia are now part of the European Union and NATO, which mostly comprise Western countries. These countries were both heavily influenced by and influenced the Western World, and share sociological values and culture. The Russian culture (particularly literature, music, painting, philosophy and architecture) is classified as a part of the Western culture. Russia is often not counted politically as a part of the Western World due to contemporary political isolationism of the country.[20]

In addition, there is debate among some as to whether Israel is part of the West. Although geographically Israel is located in the Middle East south of Lebanon, it has democratic form of government, free market economic system, high standard of living and major contributions to science. According to Sammy Smooha, a professor emeritus of sociology at Haifa University, Israel is described as a “hybrid,” a modern and developed “semi-Western” state. With the passage of time, he acknowledged, Israel will become ”more and more Western.” But as a result of the ongoing Arab-Israeli dispute, full Westernization will be a slow process in Israel.[21][22] Similarly, there is debate among some as to whether Japan and South Korea are part of the West. Although geographically Japan and South Korea are located in East Asia, they have democratic form of government, free market economic system, high standard of living and major contributions to Western science and technology, and could be described as “hybrid,” modern and developed “semi-Western” states.

Western culture

| History of Western philosophy |

|---|

|

| Western philosophy |

|

|

| See also |

|

|

|

|

The term "Western culture" is used very broadly to refer to a heritage of social norms, ethical values, traditional customs, religious beliefs, political systems, and specific artifacts and technologies.

Specifically, Western culture may imply:

- a Biblical Christian cultural influence in spiritual thinking, customs and either ethic or moral traditions, around the Post-Classical Era and after.

- European cultural influences concerning artistic, musical, folkloric, ethic and oral traditions, whose themes have been further developed by Romanticism.

- a Graeco-Roman Classical and Renaissance cultural influence, concerning artistic, philosophic, literary, and legal themes and traditions, the cultural social effects of migration period and the heritages of Celtic, Germanic, Slavic and other ethnic groups, as well as a tradition of rationalism in various spheres of life, developed by Hellenistic philosophy, Scholasticism, Humanisms, the Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment.

The concept of Western culture is generally linked to the classical definition of the Western world. In this definition, Western culture is the set of literary, scientific, political, artistic and philosophical principles that set it apart from other civilizations. Much of this set of traditions and knowledge is collected in the Western canon.[23]

The term has come to apply to countries whose history is strongly marked by European immigration or settlement, such as the Americas, and Oceania, and is not restricted to Europe.

Some tendencies that define modern Western societies are the existence of political pluralism, laicism, generalization of middle class, prominent subcultures or countercultures (such as New Age movements), increasing cultural syncretism resulting from globalization and human migration. The modern shape of these societies is strongly based upon the Industrial Revolution and the societies' associated social and environmental problems, such as class struggle and pollution, as well as reactions to them, such as syndicalism and environmentalism.

Historical divisions

The geopolitical divisions in Europe that created a concept of East and West originated in the Roman Empire.[24] The Eastern Mediterranean was home to the highly urbanized cultures that had Greek as their common language (owing to the older empire of Alexander the Great and of the Hellenistic successors.), whereas the West was much more rural in its character and more readily adopted Latin as its common language. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Western and Central Europe was substantially cut off from the East where Byzantine Greek culture and Eastern Christianity became founding influences in the Arab/Muslim world and among the Eastern and Southern Slavic peoples. Roman Catholic Western and Central Europe, as such, maintained a distinct identity particularly as it began to redevelop during the Renaissance. Even following the Protestant Reformation, Protestant Europe continued to see itself as more tied to Roman Catholic Europe than other parts of the perceived civilized world.

Use of the term West as a specific cultural and geopolitical term developed over the course of the Age of Exploration as Europe spread its culture to other parts of the world. In the past two centuries the term Western world has sometimes been used synonymously with Christian world because of the numerical dominance of Roman Catholicism and Protestantism compared to other Christian traditions, ancient Roman ideas, and heresies. As secularism rose in Europe and elsewhere during the 19th and 20th centuries, the term West came to take on less religious connotations and more political connotations, especially during the Cold War. Additionally, closer contacts between the West and Asia and other parts of the world in recent times have continued to cloud the use and meaning of the term.

Hellenic

The Hellenic division between the barbarians and the Greeks contrasted in many societies the Greek-speaking culture of the Greek settlements around the Mediterranean to the surrounding non-Greek cultures. Herodotus considered the Persian Wars of the early 5th century BC a conflict of Europa versus Asia[citation needed] (which he considered all land north and east of the Sea of Marmara, respectively)[citation needed]. The terms "West" and "East" were not used by any Greek author to describe that conflict. The anachronistic application of those terms to that division entails a stark logical contradiction, given that, when the term "West" appeared, it was used in opposition to the Greeks and Greek-speaking culture.[citation needed]

Western society traces its cultural origins, at least partially, to Greek thought and Christian religion, thus following an evolution that began in ancient Greece and the Levant, continued through the Roman Empire, and spread throughout Europe. The inherently "Greek" classical ideas of history (which one might easily say they invented) and art may, however, be considered almost inviolate in the West, as their original spread of influence survived the Hellenic period of Roman classical antiquity, The Dark Ages, its resurgence during the Western Renaissance, and has managed somehow to keep and exert its pervasive influence down into the present age, with every expectation of it continuing to dominate any secular Western cultural developments.

However, the conquest of the Western parts of the Roman Empire by Germanic peoples and the subsequent dominance by the Western Christian Papacy (which held combined political and spiritual authority, a state of affairs absent from Greek civilization in all its stages), resulted in a rupture of the previously existing ties between the Latin West and Greek thought,[25] including Christian Greek thought. The Great Schism and the Fourth Crusade confirmed this deviation.

On the other hand, the Modern West, emerging after the Renaissance as a new civilization, has been greatly influenced by (its own interpretation of) Greek thought, which was preserved in the Roman Empire and the medieval Islamic world during the Medieval West's Dark Ages and transmitted from there by emigration of Greek scholars, courtly marriages, and Latin translations. The Renaissance in the West emerged partly from currents within the Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

Roman Empire

Ancient Rome (510 BC-AD 476) was a civilization that grew from a city-state founded on the Italian Peninsula about the 9th century BC to a massive empire straddling the Mediterranean Sea. In its 12-century existence, Roman civilization shifted from a monarchy, to a republic, to an autocratic empire. It came to dominate Western, Central and Southeastern Europe and the entire area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea through conquest using the Roman legions and then through cultural assimilation by giving Roman privileges and eventually citizenship to the whole empire. Nonetheless, despite its great legacy, a number of factors led to the eventual decline of the Roman Empire.

The Western Roman Empire eventually broke into several kingdoms in the 5th century due to civil wars, corruption, and devastating Germanic invasions from such tribes as the Goths, the Franks and the Vandals.

The Eastern Roman Empire, governed from Constantinople, is usually referred to as the Byzantine Empire after 476, the traditional date for the "fall of the Western Roman Empire" and for the subsequent onset of the Early Middle Ages. The Eastern Roman Empire survived the fall of the West, and protected Roman legal and cultural traditions, combining them with Greek and Christian elements, for another thousand years.

The Roman Empire succeeded the about 500 year-old Roman Republic (510 BC - 1st century BC), which had been weakened by the conflict between Gaius Marius and Sulla and the civil war of Julius Caesar against Pompey and Marcus Brutus. During these struggles hundreds of senators were killed, and the Roman Senate had been refilled with loyalists of the First Triumvirate and later those of the Second Triumvirate.

Several dates are commonly proposed to mark the transition from Republic to Empire, including the date of Julius Caesar's appointment as perpetual roman dictator (44 BC), the victory of Caesar's heir Octavian at the Battle of Actium (September 2, 31 BC), and the Roman Senate's granting to Octavian the honorific Augustus. (January 16, 27 BC). Octavian/Augustus officially proclaimed that he had saved the Roman Republic and carefully disguised his power under republican forms: Consuls continued to be elected, tribunes of the plebeians continued to offer legislation, and senators still debated in the Roman Curia. However, it was Octavian who influenced everything and controlled the final decisions, and in final analysis, had the legions to back him up, if it became necessary.

Roman expansion began long before the state was changed into an empire and reached its zenith under emperor Trajan with the conquest of Dacia in AD 106. During this territorial peak, the Roman Empire controlled about 5 900 000 km² (2,300,000 sq.mi.) of land surface and had a population of 100 million. From the time of Caesar to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, Rome dominated Western Eurasia (as well as the Mediterranean coast of northern Africa) comprising the majority of its population, and trading with population living outside it through trade (Amber Roads). Ancient Rome has contributed greatly to the development of law, war, art, literature, architecture, technology and language in the Western world, and its history continues to have a major influence on the world today. Latin has been the base from which Roman Languages evolved and it has been the official language of the Catholic Church and all religious ceremonies all over Europe until 1967, as well as an or the official language of countries such as Poland (9th–18th centuries).[26]

The Roman Empire is where the idea of the "West" began to emerge. Due to Rome's central location at the heart of the Empire, "West" and "East" were terms used to denote provinces West and east of the capital itself. Therefore, Iberia (Portugal and Spain), Gaul (France), Mediterranean coast of North Africa (Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco) and Britannia were all part of the "West", while Greece, Anatolia, Syria, and Egypt were part of the "East." Italy itself was considered central, until the reforms of Diocletian, when the idea of formally dividing the Empire into true two halves: Eastern and Western.

In 395, the Roman Empire formally split into a Western Roman Empire and an Eastern one, each with their own emperors, capitals, and governments, although ostensibly they still belonged to one formal Empire. The dissolution of the Western half (nominally in 476, but in truth a long process that ended by 500) left only the Eastern Roman Empire alive. For centuries, the East continued to call themselves Eastern Romans, while the West began to think in terms of Latins (those living in the old Western Empire) and Greeks (those inside the Roman remnant to the east).

Christian schism

In the early 4th century, the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great established the city of Constantinople as the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Eastern Roman Empire included lands east of the Adriatic Sea and bordering on the Eastern Mediterranean and parts of the Black Sea. This division into Eastern and Western Roman Empires was reflected in the administration of the Christian Church, with Rome and Constantinople debating over whether either city was the capital of Christianity.

As the Eastern (Orthodox) and Western (firstly Catholic, then Protestant as well) churches spread their influence, the line between Eastern and Western Christianity was moving. Its movement was affected by the influence of the Byzantine empire and the fluctuating power and influence of the church in Rome. Beginning in the Middle Ages religious cultural hegemony slowly waned in Europe generally. This process may have prompted the geographic line of religious division to approximately follow a line of cultural divide.[citation needed]

Huntington argued that this cultural division still existed during the Cold War as the approximate Western boundary of those countries that were allied with the Soviet Union. Others have fiercely criticized these views arguing they confuse the Eastern Roman Empire with Russia, especially considering the fact that the country that had the most historical roots in Byzantium, Greece, expelled communists and was allied with the West during the Cold War. Still, Russia accepted Eastern Christianity from the Byzantine Empire (by the Patriarch of Constantinople: Photios I) linking Russia very close to the Eastern Roman Empire world. Later on, in 16th century Russia created its own religious centre in Moscow. Religion survived in Russia beside severe persecution carrying values alternative to the communist ideology.

Under Charlemagne, the Franks established an empire that was recognized as the Holy Roman Empire by the Pope in Rome, offending the Roman Emperor in Constantinople. The crowning of the Emperor by the Pope led to the assumption that the highest power was the papal hierarchy, establishing, until the Protestant Reformation, the civilization of West Christendom. The Latin Rite Christian Church of western and central Europe headed by the Pope split with the eastern, Greek-speaking Patriarchates during the Great Schism. Meanwhile, the extent of each expanded, as British Isles, Germanic peoples, Bohemia, Poland, Hungary, Scandinavia, Baltic peoples and the other non-Christian lands of the northwest were converted by the West Church, while Bulgaria, Romania, Russia, Belarus, Serbia, Caucasus and most of Ukraine were converted by the Eastern Church.

In this context, the Protestant reformation may be viewed as a schism within the Latin Church. Martin Luther, in the wake of precursors, broke with the pope and with the emperor, backed by many of the German princes. These changes were adopted by the Scandinavian kings. Later, the commoner Jean Cauvin (John Calvin) assumed the religio-political leadership in Geneva, a former ecclesiastical city whose prior ruler had been the bishop. The English King later improvised on the Lutheran model, but subsequently many Calvinist doctrines were adopted by popular dissenters, leading to the English Civil War.

Both royalists and dissenters colonized North America, eventually resulting in an independent United States of America.

Colonial "West"

The Reformation, and consequent dissolution of West Christendom as even a theoretical unitary political body, resulted in the Thirty Years War. The war ended in the Peace of Westphalia, which enshrined the concept of the nation-state and the principle of absolute national sovereignty in international law.

These concepts of a world of nation-states, coupled with the ideologies of the Enlightenment, the coming of modernity, the Scientific Revolution,[27] and the Industrial Revolution,[28] produced powerful political and economic institutions that have come to influence (or been imposed upon) most nations of the world today. Historians agree that the Industrial Revolution was one of the most important events in history.[29]

This process of influence (and imposition) began with the voyages of discovery, colonization, conquest, and exploitation of Spain and Portugal; it continued with the rise of the Dutch East India Company, and the creation and expansion of the British and French colonial empires. Due to the reach of these empires, Western institutions expanded throughout the world. Even after demands for self-determination from subject peoples within Western empires were met with decolonization, these institutions persisted. One specific example was the requirement that post-colonial societies were made to form nation-states (in the Western tradition), which often created arbitrary boundaries and borders that did not necessarily represent a whole nation, people, or culture, and are often the cause of international conflicts and friction even to this day. Though the overt colonial era has passed, Western nations, as comparatively rich, well-armed, and culturally powerful states, still wield a large degree of influence throughout the world.

Although not part of Western colonization process proper, Western culture entered Japan primarily in the so-called Meiji period (1868–1912), though earlier contact with the Portuguese, the Spaniards and the Dutch were also present in the recognition of European nations as strategically important to the Japanese. The traditional Japanese society was virtually overturned into an industrial and militarist power like Western countries such as the United Kingdom.

Cold War context

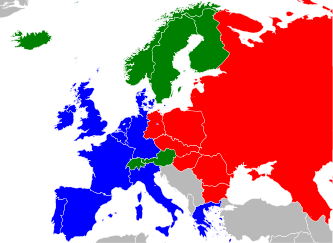

During the Cold War, a new definition emerged. Earth was divided into three "worlds". The First World, analogous in this context to what was called the West, was composed of NATO members and other countries aligned with the United States. The Second World was the Eastern bloc in the Soviet sphere of influence, including the Soviet Union (15 republics including presently independent Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) and Warsaw Pact countries like Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, East Germany (now united with Germany), Czechoslovakia (now split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia).

The Third World consisted of countries, many of which were unaligned with either, and important members included India, Yugoslavia, Finland (Finlandisation) and Switzerland (Swiss Neutrality); some include the People's Republic of China, though this is disputed,[citation needed] as the People's Republic of China is communist, had friendly relations—at certain times—with the Soviet bloc, and had a significant degree of importance in global geopolitics. Some Third World countries aligned themselves with either the US-led West or the Soviet-led Eastern bloc. [citation needed]

European trade blocs as of the late 1980s. EEC member states are marked in blue, EFTA – green, and Comecon – red. |

East and West in 1980, as defined by the Cold War. The Cold War had divided Europe politically into East and West, with the Iron Curtain splitting Central Europe. |

A number of countries did not fit comfortably into this neat definition of partition, including Switzerland, Sweden, Austria, and Ireland, which chose to be neutral. Finland was under the Soviet Union's military sphere of influence (see FCMA treaty) but remained neutral, was not communist, nor was it a member of the Warsaw Pact or Comecon but a member of the EFTA since 1986, and was West of the Iron Curtain. In 1955, when Austria again became a fully independent republic, it did so under the condition that it remain neutral, but as a country to the West of the Iron Curtain, it was in the United States' sphere of influence. Spain did not join the NATO until 1982, towards the end of the Cold War and after the death of the authoritarian Franco.

Modern definitions

The exact scope of the Western world is somewhat subjective in nature, depending on whether cultural, economic, spiritual or political criteria are employed.

Many anthropologists, sociologists and historians oppose "the West and the Rest" in a categorical manner.[30] The same has been done by Malthusian demographers with a sharp distinction between European and non-European family systems. Among anthropologists, this includes Durkheim, Dumont and Lévi-Strauss.[30]

As the term "Western world" does not have a strict international definition, governments do not use the term in legislation of international treaties and instead rely on other definitions.

Cultural

From a cultural and sociological approach the Western world is defined as including all cultures that are directly derived from and influenced by European cultures, i.e. western Europe (e.g. France, Ireland, United Kingdom), central Europe (e.g. Germany, Poland, Switzerland), northern Europe (e.g. Sweden, Denmark, Finland), eastern Europe (e.g. Russia, Ukraine, Belarus), southeastern Europe (e.g. Bulgaria, Greece, Romania) and southern (or southwestern) Europe (e.g. Spain, Italy, Portugal), in the Americas (e.g. Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Mexico, United States, Uruguay, Venezuela), and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand). Together these countries constitute Western society.[3][4][5]

In the 20th century, Christianity declined in influence in many Western countries, mostly in the northern, central and eastern parts of Europe (Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Estonia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria) and elsewhere. Secularism (separating religion from politics and science) increased. However, while church attendance is in decline, some western countries (i.e. Italy, Poland and Portugal) believe that religion is important, and most Westerners nominally identify themselves as Christians (e.g. 59% in the UK) and attend church on major occasions, such as Christmas and Easter. In the Americas Christianity continues to play an important societal role, though in areas such as Canada, low level of religiosity is common as a result of experiencing processes of secularization similar to European ones. The official religions of the United Kingdom and some Nordic countries are forms of Christianity, even though the majority of European countries have no official religion. Despite this, Christianity, in its different forms, remains the largest faith in most Western countries.[citation needed]

Modern political

Countries of the Western world are generally considered to share certain fundamental political ideologies, including those of liberal democracy, the rule of law, human rights and a high degree of gender equality (although there are notable exceptions, especially in foreign policy). All of these are prerequisites, for example, for a state to become a full member of the European Union and therefore from modern political point of view all European Union member states from the Western, Central and Eastern Europe are considered part of the Western world.

Economic

| Very High | Low |

| High | Data unavailable |

| Medium |

Though the Cold War has ended, and some members of the former Eastern Bloc make a general movement towards liberal democracy and other beliefs held in common by traditionally Western states, most of the former Soviet republics (except Baltic states) are not considered Western because of the small presence of social and political reform, as well as the significant cultural, economic and political differences to what is known today as described by the term "The West": North America (USA and Canada), Europe (EU and EFTA member states), Australia and New Zealand.

The term "Western world" is often interchangeably used with the term First World stressing the difference between First World and the Third World or developing countries. This usage occurs despite the fact that many countries that may be geographically or culturally "Western" are developing countries. In fact, most of the Americas are developing countries, which make up a significant percentage of the West. It is also used despite many developed countries not being Western (e.g., Japan, South Korea, Singapore).

The existence of "The North" implies the existence of "The South", and the socio-economic divide between North and South. The term "the North" has in some contexts replaced earlier usage of the term "the West", particularly in the critical sense, as a more robust demarcation than the terms "West" and "East". The North provides some absolute geographical indicators for the location of wealthy countries, most of which are physically situated in the Northern Hemisphere, although, as most countries are located in the northern hemisphere in general, some have considered this distinction equally unhelpful.

The thirty high-income countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which include: Australia, Canada, Iceland, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Korea, Switzerland, the United States and the countries of the EU (except for: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta and Romania), are generally included in what used to be called developed world, although the OECD includes three countries, namely Chile, Mexico and Turkey, that are not yet fully industrial countries, but newly industrialised countries. Although Andorra, Cyprus, Hong Kong, Malta, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino, Singapore, Taiwan and Vatican City, are not members of the OECD, they might also be regarded as developed countries, because their high living standards, high per capita incomes, and their social, economical and political structure are quite similar to those of the high income OECD countries.

Other views

A series of scholars of civilization, including Arnold J. Toynbee, Alfred Kroeber and Carroll Quigley have identified and analyzed "Western civilization" as one of the civilizations that have historically existed and still exist today. Toynbee entered into quite an expansive mode, including as candidates those countries or cultures who became so heavily influenced by the West as to adopt these borrowings into their very self-identity; carried to its limit, this would in practice include almost everyone within the West, in one way or another. In particular, Toynbee refers to the intelligentsia formed among the educated elite of countries impacted by the European expansion of centuries past. While often pointedly nationalist, these cultural and political leaders interacted within the West to such an extent as to change both themselves and the West.[15]

Yet more recently, Samuel P. Huntington has taken a far more controversial approach, forging a political science hypothesis he labeled the "The Clash of Civilizations?" in a Foreign Affairs article and a book.[31] According to Huntington's hypothesis, what he calls "conflicts between civilizations" will be the primary tensions of the 21st century world. In this hypothesis, the West is based on religion, as the countries of West and Central Europe were historically influenced by the two forms of Western Christianity, namely Protestantism and Catholicism. Also, some Anglophone countries share these traits, e.g. Bermuda, Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, Palau, Australia and New Zealand, as well as the more heterogeneous United States and Canada. The identification of Western Civilization with the Western Christianity (Catholic-Protestant) was not Huntington's original idea, it was rather the traditional Western viewpoint and subdivision before the Cold War era.[2]

Huntington's thesis, while influential, was by no means universally accepted; its supporters say that it explains modern conflicts, such as those in the former Yugoslavia. The thesis's detractors fear that by equating values like democracy with the concept of "Western civilization", it reinforces stereotypes that some perceive as being common within the West about non-traditionally Western societies that some may consider racist or xenophobic. Others believe that Huntington ignores the existence of non-Western democracies such as the East Asian and South-Central Asian democracies. As such, these detractors believe that it will provoke and amplify conflict rather than illuminate a way to find an accommodating world order—or, in particular cases, a commonly agreed solution.

In Huntington's narrow thesis, the historically Eastern Orthodox nations of Southeastern and Eastern Europe constitute a distinct "Euro-Asiatic civilization"; although European and mainly Christian (as well as notable Muslim influence and populations, particularly in the southeastern Europe and southern/central Russia), these nations were not, in Huntington's view, shaped by the cultural influences of the Renaissance. The Renaissance did not affect Orthodox Eastern Europe due in part to the proximity of Ottoman domination, despite the decisive influence of Greek émigré scholars on the Renaissance.[32]

Other views might be made regarding Hungary and Russia.[33]

The theologian and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin conceived of the West as the set of civilizations descended from the Nile Valley Civilization of Egypt.[34]

Palestinian-American literary critic Edward Said uses the term occident in his discussion of orientalism. According to his binary, the West, or Occident, created a romanticized vision of the East, or Orient to justify colonial and imperialist intentions. This Occident-Orient binary focuses on the Western vision of the East instead of any truths about the East. His theories are rooted in Hegel's Master-slave dialectic: The Occident would not exist without the Orient and vice versa. Further, Western writers created this irrational, feminine, weak "Other" to contrast with the rational, masculine, strong West because of a need to create a difference between the two that would justify imperialist ambitions, Said influenced Indian-American theorist Homi K. Bhabha.

The term the "West" may also be used pejoratively by certain tendencies and especially critical of the influence of the traditional West, due to the history of most of the members of the traditional West being previously involved, at one time or another, in outright imperialism and colonialism. Some of these critics also claim that the traditional West has continued to engage in what might be viewed as modern implementations of imperialism and colonialism, such as neoliberalism and globalization. (It should be noted that many Westerners who subscribe to a positive view of the traditional West are also very critical of neoliberalism and globalization, for their allegedly negative effects on both the developed and developing world.)

Allegedly, definitions of the term "Western world" that some may consider "ethnocentric" others consider "constructed" around one or another Western culture. The British writer Rudyard Kipling wrote about this contrast: East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet, expressing his belief that somebody from the West "can never understand the Asian cultures" as the latter "differ too much" from the Western cultures. Some may view this alleged incompatibility as a precursor to Huntington's "clash of civilizations" theory.

Paradoxically, today Asia and Africa to varying degrees may be considered quasi-Western. Many East Asians and South Asians and Africans and others associate or even identify with the cosmopolitan cultures and international societies referred to sometimes as Western. Likewise, many in the West identify with a transcultural humanity, a notion often found in visions of the sacred.

From a very different perspective, it has also been argued that the idea of the West is, in part, a non-Western invention, deployed in the non-West to shape and define non-Western pathways through or against modernity.[35]

Huntington on Latin America

A controversial theory of Huntington is that he considered the possibility of Latin America being a separate civilization from the West, but also mused that it might become a third part (the first two being North America and Europe, forgetting Oceania) of the West in the future. The term Latin America in itself is a French invention to denote American countries of Iberian heritage to remember them in a way of their closer linguistic and cultural relatives in Europe, and an approach to diminish the growing influence of the Anglosphere countries in the region, and some countries, such as Portuguese-speaking, largely either itself-identified or Lusophone-identified (rather than latino-identified, a – mostly Hispanic – strongly shared identity that generally emerges while in diaspora rather than natively), historically largely Francophile Brazil, and Marxist-Leninist, historically largely Hispanophile Cuba, do not necessarily fit more to the group in relation to other Western nations in various factors. Therefore, many believe this view would be another event of U.S. American generalizations and little knowledge on the region's cultures' and peoples' realities and their individualities.

Huntington did not present any evidence that Latin Americans see themselves as foreign in comparison to other Western cultures, or even a probably existing Western point-of-view of Latin Americans as foreigners in relation to Europeans and their direct descendants (though hardly for reasons other than the mixed-race descent pervasive among them, as, just like in its ruling colonial powers, both the Renaissance and the Enlightenment were strongly felt in the region). With the Latin American racial whitening policies, reflecting a still living regional tendency to the preference of imitating or prizing not only North American and European appearance, but also fashion, cultural taste and items, political values and even lexicon or given names (known as mentalidade de colonizado, "colonized mentality", in Portuguese), it seems more ludicrous that the reality is most often quite the reverse, i.e., that Latin Americans, especially those from Brazil and the Southern Cone, would be readily phobic about being otherized by Westerners and put in the same category as their often ridiculed or disparaged worker classes and rural people, or poorer neighboring and close cultural relative nations, and thus, as a consequence, also phobic to being seen as collectively very "different" or "especial" in general.

See also

- Americanization

- Anglicisation

- Atlanticism

- Eastern world

- Europeanisation

- Francophonie

- Golden billion

- Hispanophone

- Russification

- Russophone

- Western esotericism

- Western philosophy

- Westernization

- Organisations

- Council of Europe

- European Economic Area

- Group of Eight

- Representation in the UN

Maps

-

Latin alphabet world distribution. The dark green areas show the countries where this alphabet is the sole main script. The light green places show the countries where the alphabet co-exists with other scripts

-

Religions of the world, mapped by distribution.

-

Map showing relative degree of religiosity by country. Based on a 2006-2008 worldwide survey by Gallup.

-

.png)

Human language families

-

Western Palaearctic, a part of the Palaearctic ecozone, one of the eight ecozones dividing the Earth's surface

-

Geopoliticall Occident of Europe

References

- ↑ Western Civilization, Our Tradition; James Kurth; accessed 30 August 2011

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 |Google books results in English language between the 1800 - 1960 period

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Thompson, William; Hickey, Joseph (2005). Society in Focus. Boston, MA: Pearson. 0-205-41365-X.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Embassy of Brazil - Ottawa". Brasembottawa.org. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Falcoff, Mark. "Chile Moves On". AEI. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ "The Evolution of Civilizations - An Introduction to Historical Analysis (1979)". Archive.org. 2001-03-10. p. 84. Retrieved 2014-01-31.

- ↑ Middle Ages

Of the three great civilizations of Western Eurasia and North Africa, that of Christian Europe began as the least developed in virtually all aspects of material and intellectual culture, well behind the Islamic states and Byzantium.

- ↑ H. G. Wells, The Outline of History, Section 31.8, The Intellectual Life of Arab Islam

For some generations before Muhammad, the Arab mind had been, as it were, smouldering, it had been producing poetry and much religious discussion; under the stimulus of the national and racial successes it presently blazed out with a brilliance second only to that of the Greeks during their best period. From a new angle and with a fresh vigour it took up that systematic development of positive knowledge, which the Greeks had begun and relinquished. It revived the human pursuit of science. If the Greek was the father, then the Arab was the foster-father of the scientific method of dealing with reality, that is to say, by absolute frankness, the utmost simplicity of statement and explanation, exact record, and exhaustive criticism. Through the Arabs it was and not by the Latin route that the modern world received that gift of light and power.

- ↑ Lewis, Bernard (2002). What Went Wrong. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780060516055.

For many centuries the world of Islam was in the forefront of human civilization and achievement.... In the era between the decline of antiquity and the dawn of modernity, that is, in the centuries designated in European history as medieval, the Islamic claim was not without justification.

- ↑ "Science, civilization and society". Es.flinders.edu.au. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ Richard J. Mayne, Jr. "Middle Ages". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ InfoPlease.com, commercial revolution

- ↑ "The Scientific Revolution". Wsu.edu. 1999-06-06. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ Eric Bond, Sheena Gingerich, Oliver Archer-Antonsen, Liam Purcell, Elizabeth Macklem (2003-02-17). "Innovations". The Industrial Revolution. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cf., Arnold J. Toynbee, Change and Habit. The challenge of our time (Oxford 1966, 1969) at 153-156; also, Toynbee, A Study of History (10 volumes, 2 supplements).

- ↑ Auster, Lawrence (2006-04-03). "Are Hispanics Westerners? The Debate Continues". Amnation.com. Retrieved 2014-01-31.

- ↑ BUDAPEST - Ghost of second-class status haunts central and eastern Europe

- ↑ Z. Lerman, C. Csaki, and G. Feder, Agriculture in Transition: Land Policies and Evolving Farm Structures in Post-Soviet Countries, Lexington Books, Lanham, MD (2004), see, e.g., Table 1.1, p. 4.

- ↑ J. Swinnen, ed., Political Economy of Agrarian Reform in Central and Eastern Europe, Ashgate, Aldershot (1997).

- ↑ "Russia: Between interventionism and isolationism | Opinions | RIA Novosti". En.ria.ru. Retrieved 2014-01-31.

- ↑ Sheldon Kirshner (2013-10-16). "Is Israel Really a Western Nation?". Sheldon Kirshner Journal. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ↑ Gideon Levy (2009-12-10). "Gideon Levy / Let's face the facts, Israel is a semi-theocracy". Haaretz. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ↑ Duran 1995, p.81

- ↑ Bideleux,Robert; Jeffries, Ian. A history of eastern Europe: crisis and change. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-415-16112-1.

- ↑ Charles Freeman. The Closing of the Western Mind. Knopf, 2003. ISBN 1-4000-4085-X

- ↑ Karin Friedrich et al., The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569–1772, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-58335-7, Google Print, p.88

- ↑ "Modern West Civ. 7: The Scientific Revolution of the 17 Cent". Fordham.edu. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ "The Industrial Revolution". Mars.wnec.edu. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ Industrial Revolution and the Standard of Living: The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, Library of Economics and Liberty

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "New Left Review - Jack Goody: The Labyrinth of Kinship". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ↑ Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (1996).

- ↑ Scholars such as Georgios Gemistos Plethon, Manuel Chrysoloras, Theodorus of Gaza, Ioannis Argyropoulos, Markos Mousouros and Demetrius Chalcondyles.

- ↑ The Renaissance was said to be weak in the frontier region of Hungary because Ottoman military pressure long limited Hungarian access to their fellow Roman Catholics in Austria. Yet regarding Hungary, such views depart from the consensus. Some claim the reforms of Peter the Great (1682-1725) and Catherine II the Great (1762-96) were inspired by the Enlightenment. However, they departed considerably from the Enlightenment idea of respect for the individual: Peter's projects for St Petersburg cost the lives of 30,000 workers (though such loss of life was not unknown in the rest of Europe), and under both Peter and Catherine most Russians remained serfs. It is unclear whether these views are those of Huntington or not.

- ↑ Cf., Teilhard de Chardin, Le Phenomene Humain (1955), translated as The Phenomena of Man (New York 1959).

- ↑ Bonnett, A. 2004. The Idea of the West

Further reading

- Ankerl, Guy (2000). Coexisting contemporary civilizations : Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and West. INU societal research. Vol.1:. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

- Bavaj, Riccardo: "The West": A Conceptual Exploration , European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2011, retrieved: November 28, 2011.

- Duchesne, Ricardo (2011): The Uniqueness of Western Civilization, Studies in Critical Social Sciences, Vol. 28, Leiden and Boston: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-19248-5

- J. F. C. Fuller. A Military History of the Western World. Three Volumes. New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1987 and 1988.

- V. 1. From the earliest times to the Battle of Lepanto; ISBN 0-306-80304-6.

- V. 2. From the defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo; ISBN 0-306-80305-4.

- V. 3. From the American Civil War to the end of World War II; ISBN 0-306-80306-2.

| ||||||||||||||||

| |||||