West Point Foundry

|

West Point Foundry | |

| |

|

The house of William Kemble, one of the company's founders, seen from the parking lot of the Cold Spring Metro-North station | |

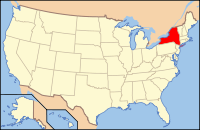

| Location | Cold Spring, NY |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Beacon |

| Coordinates | 41°24′51″N 73°57′22″W / 41.41417°N 73.95611°WCoordinates: 41°24′51″N 73°57′22″W / 41.41417°N 73.95611°W |

| Area | 87 acres (35 ha) |

| Built | 1817 |

| Governing body | Scenic Hudson |

| NRHP Reference # | 73001250 |

| Added to NRHP | 1973 |

The West Point Foundry was an early ironworks in Cold Spring, New York that operated from 1817 to 1911. Set up to remedy deficiencies in national armaments production after the War of 1812, it became most famous for its production of Parrott rifles and other munitions during the Civil War, although it also manufactured a variety of iron products for civilian use. The rise of steel making and declining demand for cast iron after the Civil War caused it to gradually sink into bankruptcy and cease operations in the early 20th Century.

Founding and early products

The impetus for its creation came from James Madison, who, after the War of 1812, wanted to establish domestic foundries to produce artillery.[1] Cold Spring was an ideal site: timber for charcoal was abundant, there were many local iron mines, and the nearby Margaret's Brook provided water power to drive machinery. The site was guarded by West Point, across the Hudson River, and the river provided shipping for finished products.[2]

The West Point Foundry Association was incorporated by Gouverneur Kemble, who came from a merchant family in New York City (although his mother's family had connections in Putnam Co.), and the foundry began operation in 1817.[2] Artillery was tested by firing across the Hudson at the desolate slopes of Storm King Mountain, which would have to be swept for unexploded ordnance as a result after some of it exploded in a 1999 fire.[3] The platform used for mounting artillery for proofing was uncovered during Superfund work in the early 1990s.[4] Besides artillery, the foundry also produced iron fittings for civilian uses, such as pipe for the New York City water system and sugar mills for shipment to the West Indies. A number of early locomotives were built at the foundry, including the Best Friend of Charleston, the West Point, the DeWitt Clinton, Phoenix, and Experiment.[2]

Parrott years and the Civil War

In 1835, Captain Robert Parker Parrott, a West Point graduate, was appointed inspector of ordnance from the foundry. The next year, he resigned his commission and on October 31, 1836 was appointed superintendent of the foundry. It prospered under his tenure, and was the site of numerous experiments with artillery and projectiles, culminating in his invention of the Parrott rifle in 1860.[5] During Parott's tenure, in 1843, the foundry also manufactured USS Spencer, a revenue cutter which was the first iron ship built in the U.S.[2]

The foundry's operations peaked during the Civil War due to military orders: it had a workforce of 1,400 people and produced 2,000 cannon and three million shells.[2] Parrott also invented an incendiary shell which was used in an 8-inch Parrott rifle (the "Swamp Angel") to bombard Charleston. The importance of the foundry to the war effort can be measured by the fact that President Abraham Lincoln visited and inspected it in June 1862.[6]

The fame of the foundry was such that Jules Verne, in his novel From the Earth to the Moon, chose it as the contractor for the Columbiad spaceship-launching cannon.[7]

Decline and archaeology

In 1867, Parrott resigned as superintendent, although he continued to experiment with artillery designs until his death in 1877.[8] Business at the foundry declined as it faced competition from more modern techniques of iron and steel production. It had discontinued the use of charcoal and begun to import coal from Pennsylvania around 1870. However, it was unable to stave off receivership in 1884 and bankruptcy in 1889.[9] It was sold in 1897 to the Cornell brothers, makers of sugar mills, and closed in 1911.[2]

Of the buildings on the site, only the central office building remains intact; the rest are in ruins. 87 acres (35 ha) around the site form a preserve owned by Scenic Hudson.[10] It can be visited by a short trail from the nearby Cold Spring Metro-North station. A major archaeological study of the site, funded by Scenic Hudson and undertaken by Michigan Tech, has taken place from 2002-2008.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ ref. needed

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "History of West Point Foundry (archived)". Archived from the original on 2007-06-29. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ↑ "Corps of Engineers Cleanup Projects". Archived from the original on 2006-12-10. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ↑ "Foundry Cove Archaeology". Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ↑ "Robert Parker Parrott". Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ↑ "Visit to West Point". Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "West Point Foundry Archaeology Project". Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ↑ "A Village Born of Iron: Trouble in the Ravine". Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ↑ "A Village Born of Iron: A Long Road Ended". Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ↑ "West Point Foundry Preserve". Retrieved 2012-08-29.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||