Warsaw Pact

| Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation, and Mutual Assistance | |||||

| Military alliance | |||||

| |||||

|

| |||||

| Motto Союз мира и социализма (Russian) "Union of peace and socialism" | |||||

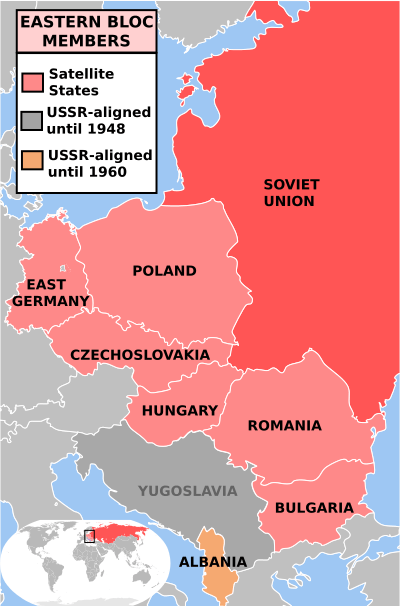

Member states of the Warsaw Pact:

| |||||

| Capital | Not specified | ||||

| Languages | Russian, Polish, German, Bulgarian, Czech, Slovak, Hungarian, Romanian, Albanian | ||||

| Political structure | Military alliance | ||||

| Supreme Commander | |||||

| - | 1955–60 (first) | Ivan Kornev | |||

| - | 1989–91 (last) | Petr Lushev | |||

| Head of Unified Staff | |||||

| - | 1955–62 (first) | Aleksei Antonov | |||

| - | 1989–90 (last) | Vladimir Lobov | |||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||

| - | Established | 14 May 1955 | |||

| - | Hungarian crisis | 4 November 1956 | |||

| - | Czechoslovakian crisis | 21 August 1968 | |||

| - | End of Communism in Poland (1989) | 13 September 1989/22 December 1990 | |||

| - | German reunification² | 3 October 1990 | |||

| - | Disestablished | 1 July 1991 | |||

| ¹ Command and Control HQ in Warsaw, Poland. Military HQ in Moscow, USSR. ² A 24 September 1990 treaty withdrew the German Democratic Republic from the Warsaw Treaty; at reunification, it became integral to the NATO Pact. | |||||

| Warsaw Pact |

|---|

|

|

Dissent and opposition 1953 uprisings

1956 protests

|

|

Cold War events

|

|

Decline |

The Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation, and Mutual Assistance,[1] more commonly referred to as the Warsaw Pact, was a mutual defense treaty between eight communist States of Central and Eastern Europe in existence during the Cold War. The founding treaty was established under the initiative of the Soviet Union and signed on 14 May 1955, in Warsaw. The Warsaw Pact was the military complement to the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CoMEcon), the regional economic organization for the communist States of Central and Eastern Europe. The Warsaw Pact was in part a Soviet military reaction to the integration of West Germany[2] into NATO in 1955, per the Paris Pacts of 1954 [3][4][5] but was primarily motivated by Soviet desires to maintain control over military forces in Central and Eastern Europe[6] which in turn (according to The Warsaw Pact's preamble) to maintain peace in Europe, guided by the objective points and principles of the Charter of the United Nations (1945).[7]

Nomenclature

In the Western Bloc, the Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance is often called the Warsaw Pact military alliance; abbreviated WAPA, Warpac, and WP. Elsewhere, in the former member states, the Warsaw Treaty is known as:

- Albanian: Pakti i miqësisë, bashkëpunimit dhe i ndihmës së përbashkët

- Bulgarian: Договор за дружба, сътрудничество и взаимопомощ

- Romanized Bulgarian: Dogovor za druzhba, satrudnichestvo i vzaimopomosht

- Czech: Smlouva o přátelství, spolupráci a vzájemné pomoci

- Slovak: Zmluva o priateľstve, spolupráci a vzájomnej pomoci

- German: Vertrag über Freundschaft, Zusammenarbeit und gegenseitigen Beistand

- Hungarian: Barátsági, együttműködési és kölcsönös segítségnyújtási szerződés

- Polish: Układ o Przyjaźni, Współpracy i Pomocy Wzajemnej

- Romanian: Tratatul de prietenie, cooperare şi asistenţă mutuală

- Russian: Договор о дружбе, сотрудничестве и взаимной помощи

- Romanized Russian: Dogovor o druzhbe, sotrudnichestve i vzaimnoy pomoshchi

Structure

The Warsaw Treaty’s organization was two-fold: the Political Consultative Committee handled political matters, and the Combined Command of Pact Armed Forces controlled the assigned multi-national forces, with headquarters in Warsaw, Poland. Furthermore, the Supreme Commander of the Unified Armed Forces of the Warsaw Treaty Organization was also a First Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR, and the head of the Warsaw Treaty Combined Staff also was a First Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Therefore, although ostensibly an international collective security alliance, the USSR dominated the Warsaw Treaty armed forces.[8]

Strategy

The strategy behind the formation of the Warsaw Pact was driven by the desire of the Soviet Union to dominate Central and Eastern Europe. This policy was driven by ideological and geostrategic reasons. Ideologically, the Soviet Union arrogated the right to define socialism and communism and act as the leader of the global socialist movement. A corollary to this idea was the necessity of intervention if a country appeared to be violating core socialist ideas and Communist Party functions, which was explicitly stated in the Brezhnev Doctrine.[9] Geostrategic principles also drove the Soviet Union to prevent invasion of its territory by Western European powers, which had occurred most recently by Nazi Germany in 1941. The invasion launched by Hitler had been exceptionally brutal and the USSR emerged from the Second World War in 1945 with the greatest total casualties of any participant in the war, suffering an estimated 27 million killed along with the destruction of much of the nation's industrial capacity.

History

Beginnings

In March 1954, the USSR, fearing "the restoration of German Militarism" in West Germany, requested to join NATO.[10][11][12] By then, laws had already passed in West Germany ending denazification [13][14] and the Gehlen Organization, predecessor of the West German Federal Intelligence Service, was fully operative and employing hundreds of ex-Nazis.[15]

The Soviet request to join NATO arose in the aftermath of the Berlin Conference of January–February 1954. Molotov made different proposals to have Germany reunified[16] and elections for a pan-German government,[17] under conditions of withdrawal of the four powers armies and German neutrality,[18] but all were refused by the other foreign ministers, Dulles (USA), Eden (UK) and Bidault (France).[19] Consequently, Molotov "seeking to prevent the formation of groups of European States directed against other European States"[20] made a proposal for a general European treaty on collective security in Europe "open to all European States without regard as to their social systems"[20] which would have included the unified Germany (thus making EDC—perceived by USSR as a threat to its own security—unusable). But again, Eden, Dulles, and Bidault opposed the proposal.[21]

One month later, the Soviets, seeing that the proposed European Treaty was perceived as "unacceptable in its present form because it excludes the USA from participation in the collective security system in Europe", decided to make a new proposal including the participation of the US in the agreement.[22] Furthermore, considering that another argument deployed against the Soviet proposal was that it was perceived as "directed against the North Atlantic Pact and its liquidation",[22][23] the Soviets decided to declare their "readiness to examine jointly with other interested parties the question of the participation of the USSR in the North Atlantic bloc", specifying that "the admittance of the USA into the General European Agreement should not be conditional on the three western powers agreeing to the USSR joining the North Atlantic Pact".[22]

Again all proposals, including the request to join NATO, were rejected by UK, US, and French governments shortly after.[12][24][25] German re-unification proposals were not new: Earlier in 1952, talks about a German reunification ended after the United Kingdom, France, and the United States insisted that a unified Germany should not be neutral and should be free to join the EDC and rearm.

On April 1954 Adenauer made his first travel to USA meeting Nixon, Eisenhower and Dulles. Ratification of EDC was delaying but the US representatives made it clear to Adenauer that EDC would have become a part of NATO.[26]

Memories of the Nazi occupation were still strong, and the rearmament of Germany was feared by France too.[27] On 30 August 1954 French Parliament rejected the EDC, thus decreeting its failure[28] and blocking a major objective of US policy towards Europe: to associate militarily Germany with the West.[29] The US Department of State started to elaborate alternatives: Germany would be invited to accede NATO or, in case of French obstructionism, strategies to circumvent a French veto would be implemented in order to obtain a German rearmament outside NATO.[30]

On 23 October 1954 – only nine years after Allies (UK, USA and USSR) defeated Nazi Germany ending World War II in Europe - the Federal Republic of Germany was finally admitted to the North Atlantic Pact. The incorporation of West Germany into the organization on 9 May 1955 was described as "a decisive turning point in the history of our continent" by Halvard Lange, Foreign Affairs Minister of Norway at the time.[31]

On 14 May 1955, the USSR and other seven European countries established the Warsaw Pact in response to the integration of the Federal Republic of Germany into NATO, declaring that: "a remilitarized Western Germany and the integration of the latter in the North-Atlantic bloc [...] increase the danger of another war and constitutes a threat to the national security of the peaceable states; [...] in these circumstances the peaceable European states must take the necessary measures to safeguard their security".[32]

During Cold War

The eight member countries of the Warsaw Pact pledged the mutual defense of any member who would be attacked. Relations among the treaty signatories were based upon mutual non-intervention in the internal affairs of the member countries, respect for national sovereignty, and political independence. However, almost all governments of those members states were directly controlled by the Soviet Union.

The founding signatories to the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance consisted of the following communist governments:

-

.svg.png) People's Republic of Albania (withheld support in 1961 because of the Sino–Soviet split, formally withdrew in 1968)

People's Republic of Albania (withheld support in 1961 because of the Sino–Soviet split, formally withdrew in 1968) -

.svg.png) People's Republic of Bulgaria

People's Republic of Bulgaria -

Czechoslovak Republic (Czechoslovak Socialist Republic since 1960)

Czechoslovak Republic (Czechoslovak Socialist Republic since 1960) -

German Democratic Republic (withdrew in September 1990, before German reunification)

German Democratic Republic (withdrew in September 1990, before German reunification) -

.svg.png) People's Republic of Hungary

People's Republic of Hungary -

People's Republic of Poland (withdrew on January 1, 1990)

People's Republic of Poland (withdrew on January 1, 1990) -

.svg.png) People's Republic of Romania

People's Republic of Romania -

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

For 36 years, NATO and the Warsaw Treaty never directly waged war against each other in Europe; the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies implemented strategic policies aimed at the containment of each other in Europe, while working and fighting for influence within the wider Cold War on the international stage.

In 1956, following the declaration of the Imre Nagy government of withdrawal of Hungary from the Warsaw Pact, Soviet troops entered the country and removed the government. Soviet forces crushed the nation-wide revolt, leading to death of an estimated 2,500 Hungarian citizens.

The multi-national Communist armed forces’ sole joint action was the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. All member countries, with the exception of the Socialist Republic of Romania and the People's Republic of Albania participated in the invasion.

End of the Cold War

Beginning at the Cold War’s conclusion, in late 1989, popular civil and political public discontent forced the Communist governments of the Warsaw Treaty countries from power – independent national politics made feasible with the perestroika- and glasnost-induced institutional collapse of Communist government in the USSR.[33] Eventually, the populaces of Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Albania, East Germany, Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria deposed their Communist governments in the period from 1989–91.

On 25 February 1991, the Warsaw Pact was declared disbanded at a meeting of defense and foreign ministers from Pact countries meeting in Hungary.[34] On 1 July 1991, in Prague, the Czechoslovak President Václav Havel formally ended the 1955 Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance and so disestablished the Warsaw Treaty after 36 years of military alliance with the USSR. The treaty was de facto disbanded in December 1989 during the violent revolution in Romania that toppled the communist government there. The USSR disestablished itself in December 1991.

Central and Eastern Europe after the Warsaw Treaty

On 12 March 1999, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland joined NATO; Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, and Slovakia joined in March 2004; Croatia and Albania joined on 1 April 2009.

Russia and some other post-USSR states joined in the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO).

In November 2005, the Polish government opened its Warsaw Treaty archives to the Institute of National Remembrance, who published some 1,300 declassified documents in January 2006. Yet the Polish government reserved publication of 100 documents, pending their military declassification. Eventually, 30 of the reserved 100 documents were published; 70 remained secret, and unpublished. Among the documents published is the Warsaw Treaty's nuclear war plan, Seven Days to the River Rhine – a short, swift attack capturing Austria, Denmark, Germany and Netherlands east of River Rhine, using nuclear weapons, in self-defense, after a NATO first strike. The plan originated as a 1979 field training exercise war game, and metamorphosed into official Warsaw Treaty battle doctrine, until the late 1980s – which is why the People’s Republic of Poland was a nuclear weapons base, first, to 178, then, to 250 tactical-range rockets. Doctrinally, as a Soviet-style (offensive) battle plan, Seven Days to the River Rhine gave commanders few defensive-war strategies for fighting NATO in Warsaw Treaty territory.[citation needed]

Gallery

<gallery style=widths="150px" heights="120px" perrow="4"> Image:Знак Варшавского договора.JPG|Badge Warsaw Pact. Union of peace and socialism Image:Знак Варшавского договра ЮГ.JPG|Badge Warsaw Pact. Brothers in arms (1970) Image:Знак Варшавского договора 1972.JPG|Badge A participant in joint exercises of Warsaw Pact "STIT" (1972) Image:Значок Варшавского договора, 25 лет.JPG|Badge 25 years Warsaw Pact (1980) Image:Значок ВВС Варшавского договора.JPG|AIR FORCE air forces Warsaw Pact Image:Значок Варшавского договора ЩИТ-82.JPG|Badge Warsaw Pact. The participants of the joint exercises in Bulgaria (1982) Image:Знак 30 лет Варшавского договора.JPG|Jubilee badge 30 years of the Warsaw Pact (1985) </gallery>

Notes

- ↑ "Text of Warsaw Pact". United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 2013-08-22.

- ↑ Yost, David S. (1998). NATO Transformed: The Alliance's New Roles in International Security. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press. p. 31. ISBN 1-878379-81-X.

- ↑ Broadhurst, Arlene Idol (1982). The Future of European Alliance Systems. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-86531-413-6.

- ↑ Christopher Cook, Dictionary of Historical Terms (1983)

- ↑ The Columbia Enclopedia, fifth edition (1993) p. 2926

- ↑ "Warsaw Pact: Wartime Status-Instruments of Soviet Control". Wilson Center. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Полный текст Варшавского Договора (1955)". The Warsaw Pact (1955) - Official version of the document. Дирекция портала "Юридическая Россия". Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ↑ Fes'kov, V. I.; Kalashnikov, K. A.; Golikov, V. I. (2004). Sovetskai͡a Armii͡a v gody "kholodnoĭ voĭny," 1945–1991 [The Soviet Army in the Cold War Years (1945–1991)]. Tomsk: Tomsk University Publisher. p. 6. ISBN 5-7511-1819-7.

- ↑ ' 'The Review of Politics Volume' ', 34, No. 2 (April 1972), pp. 190-209

- ↑ "Soviet Union request to join NATO". Nato.int. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- ↑ "Fast facts about NATO". CBC News. 6 April 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Proposal of Soviet adherence to NATO as reported in the Foreign Relations of the United States Collection". UWDC FRUS Library. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- ↑ Art, David, The politics of the Nazi past in Germany and Austria, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 53-55

- ↑ Wahl 2007, p. 92-108.

- ↑ Höhne, Heinz; Zolling, Hermann, The General Was a Spy: The Truth about General Gehlen and his spy ring, New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan 1972, p. 31

- ↑ Molotov 1954a, p. 197,201.

- ↑ Molotov 1954a, p. 202.

- ↑ Molotov 1954a, p. 197-198,203,212.

- ↑ Molotov 1954a, p. 211-212,216.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Draft general European Treaty on collective security in Europe — Molotov proposal (Berlin, 10 February 1954)". CVCE. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ Molotov 1954a, p. 214.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "MOLOTOV'S PROPOSAL THAT THE USSR JOIN NATO, MARCH 1954". Wilson Center. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ Molotov 1954a, p. 216,.

- ↑ "Final text of tripartite reply to Soviet note". Nato website. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- ↑ "Memo by Lord Ismay, Secretary General of NATO". Nato.int. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- ↑ Adenauer 1966a, p. 662.

- ↑ "The refusal to ratify the EDC Treaty". CVCE. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ "Debates in the French National Assembly on 30 August 1954". CVCE. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ "US positions on alternatives to EDC". United States Department of State / FRUS collection. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ "US positions on german rearmament outside NATO". United States Department of State / FRUS collection. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ "West Germany accepted into Nato". BBC News. 9 May 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Text of the Warsaw Security Pact (see preamble)". Avalon Project. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- ↑ The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought, third edition, 1999, pp. 637–8

- ↑ "Warsaw Pact and Comecon To Dissolve This Week". Csmonitor.com. 1991-02-26. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

Further reading

- Havel, Václav (2007). To the Castle and Back. Trans. Paul Wilson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26641-5.

- Heuser, Beatrice (1998). "Victory in a Nuclear War? A Comparison of NATO and WTO War Aims and Strategies". Contemporary European History 7 (3): 311–327. doi:10.1017/S0960777300004264.

- Mark N. Kramer, 'Civil-military relations in the Warsaw Pact,' The East European component,' International Affairs, Vol. 61, No. 1, Winter 1984-85.

- Lewis, William Julian (1982). The Warsaw Pact: Arms, Doctrine, and Strategy. Cambridge, Mass.: Institute for Foreign Policy Analysis. ISBN 978-0-07-031746-8.

- Mastny, Vojtech; Byrne, Malcolm (2005). A Cardboard Castle ?: An Inside History of the Warsaw Pact, 1955–1991. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-7326-07-3.

- Umbach, Frank (2005). Das rote Bündnis: Entwicklung und Zerfall des Warschauer Paktes 1955 bis 1991 (in German). Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86153-362-7.

- Wahl, Alfred (2007). La seconda vita del nazismo nella Germania del dopoguerra (in Italian). Torino: Lindau. ISBN 978-8-87180-662-4. - Original Ed.: Wahl, Alfred (2006). La seconde histoire du nazisme dans l'Allemagne fédérale depuis 1945. (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 2-200-26844-0.

- Adenauer, Konrad (1966a). Memorie 1945-1953 (in Italian). Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. - English Ed.: Adenauer, Konrad (1966b). Konrad Adenauer Memoirs 1945-53. Henry Regnery Company.

- Molotov, Vyacheslav (1954a). La conferenza di Berlino (in Italian). Ed. di cultura sociale. - English Ed.: Molotov, Vyacheslav (1954b). Statements at Berlin Conference of Foreign Ministers of U.S.S.R., France, Great Britain and U.S.A., January 25-February 18, 1954. Foreign Languages Publishing House.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Warsaw Pact. |

- The Woodrow Wilson Center Cold War International History Project's Warsaw Pact Document Collection

- Parallel History Project on Cooperative Security

- Library of Congress / Federal Research Division / Country Studies / Area Handbook Series / Soviet Union / Appendix C: The Warsaw Pact (1989)

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||