Walkie-talkie

A walkie-talkie (more formally known as a handheld transceiver, or HT) is a hand-held, portable, two-way radio transceiver. Its development during the Second World War has been variously credited to Donald L. Hings ('packset' of 1937), radio engineer Alfred J. Gross, and engineering teams at Motorola. Similar designs were created for other armed forces, and after the war, walkie-talkies spread to public safety and eventually commercial and jobsite work.

Major characteristics include a half-duplex channel (only one radio transmits at a time, though any number can listen) and a "push-to-talk" (PTT) switch that starts transmission. Typical walkie-talkies resemble a telephone handset, possibly slightly larger but still a single unit, with an antenna mounted on the top of the unit. Where a phone's earpiece is only loud enough to be heard by the user, a walkie-talkie's built-in speaker can be heard by the user and those in the user's immediate vicinity. Hand-held transceivers may be used to communicate between each other, or to vehicle-mounted or base stations.

History

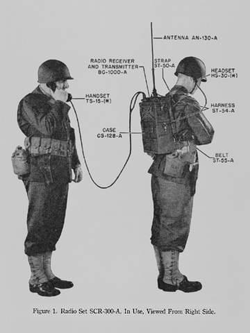

The first radio receiver/transmitter to be widely nicknamed "Walkie-Talkie" was the backpacked Motorola SCR-300, created by an engineering team in 1940 at the Galvin Manufacturing Company (fore-runner of Motorola). The team consisted of Dan Noble, who conceived of the design using frequency modulation, Henryk Magnuski who was the principal RF engineer, Marion Bond, Lloyd Morris, and Bill Vogel.

Motorola also produced the hand-held AM SCR-536 radio during World War II, and it was called the "Handie-Talkie" (HT).[1] The terms are often confused today, but the original walkie talkie referred to the back mounted model, while the handie talkie was the device which could be held entirely in the hand (but had vastly reduced performance). Both devices ran on vacuum tubes and used high voltage dry cell batteries. (Handie-Talkie became a trademark of Motorola, Inc. on May 22, 1951. The application was filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and the trademark registration number is 71560123.)

Radio engineer and developer of the Joan-Eleanor system Alfred J. Gross also worked on the early technology behind the walkie-talkie between 1934 and 1941, and is sometimes credited with inventing it.[2]

Also credited with the invention of the walkie talkie is Canadian inventor Donald Hings who created a portable radio signaling system for his employer CM&S in 1937 which he called a "packset", but which later became known as the "walkie talkie". In 2001, Hings was formally decorated for its significance to the war effort.[3][4] Hing's model C-58 "Handy-Talkie" was in military service by 1942, the result of a secret R&D effort that began in 1940.

Following World War II, Raytheon developed the SCR-536's military replacement, the AN/PRC-6. The AN/PRC-6 circuit uses 13 vacuum tubes (receiver and transmitter); a second set of 13 tubes is supplied with the unit as running spares. The unit is factory set with one crystal and may be changed to a different frequency in the field by replacing the crystal and re-tuning the unit. It uses a 24 inch whip antenna. There is an optional handset H-33C/PT that can be connected to the AN/PRC-6 by a 5 foot cable. A web sling is provided.

In the mid-1970s the Marine Corps initiated an effort to develop a squad radio to replace the unsatisfactory helmet-mounted AN/PRR-9 receiver and receiver/transmitter hand-held AN/PRT-4 (both developed by the Army). The AN/PRC-68 was first produced in 1976 by Magnavox, was issued to the Marines in the 1980s, and was adopted by the US Army as well.

The abbreviation HT, derived from Motorola's "Handie Talkie" trademark, is commonly used to refer to portable handheld ham radios, with "walkie-talkie" often used as a layman's term or specifically to refer to a toy. Public safety or commercial users generally refer to their handhelds simply as "radios". Surplus Motorola Handie Talkies found their way into the hands of ham radio operators immediately following World War II. Motorola's public safety radios of the 1950s and 1960s, were loaned or donated to ham groups as part of the Civil Defense program. To avoid trademark infringement, other manufacturers use designations such as "Handheld Transceiver" or "Handie Transceiver" for their products.

Developments

Some cellular telephone networks offer a push-to-talk handset that allows walkie-talkie-like operation over the cellular network, without dialling a call each time. However, the cellphone provider must be accessible.

Motorola has IDEN cellphones (e.g., i867) that can have 15 conversations over each of 10 900Mhz channels (see Moto Talk) between compatible cellphones without using the cellphone network or a base station. This is very useful outside the range of a cellphone provider as well as reducing network charges.

Walkie-talkies for public safety, commercial and industrial uses may be part of trunked radio systems, which dynamically allocate radio channels for more efficient use of limited radio spectrum. Such systems always work with a base station that acts as a repeater and controller, although individual handsets and mobiles may have a mode that bypasses the base station.

Contemporary use

Walkie-talkies are widely used in any setting where portable radio communications are necessary, including business, public safety, military, outdoor recreation, and the like, and devices are available at numerous price points from inexpensive analog units sold as toys up to ruggedized (i.e. waterproof or intrinsically safe) analog and digital units for use on boats or in heavy industry. Most countries allow the sale of walkie-talkies for, at least, business, marine communications, and some limited personal uses such as CB radio, as well as for amateur radio designs. Walkie-talkies, thanks to increasing use of miniaturized electronics, can be made very small, with some personal two-way UHF radio models being smaller than a deck of cards (though VHF and HF units can be substantially larger due to the need for larger antennas and battery packs). In addition, as costs come down, it is possible to add advanced squelch capabilities such as CTCSS (analog squelch) and DCS (digital squelch) (often marketed as "privacy codes") to inexpensive radios, as well as voice scrambling and trunking capabilities. Some units (especially amateur HTs) also include DTMF keypads for remote operation of various devices such as repeaters. Some models include VOX capability for hands-free operation, as well as the ability to attach external microphones and speakers.

Consumer and commercial equipment differ in a number of ways; commercial gear is generally ruggedized, with metal cases, and often has only a few specific frequencies programmed into it (often, though not always, with a computer or other outside programming device; older units can simply swap crystals), since a given business or public safety agent must often abide by a specific frequency allocation. Consumer gear, on the other hand, is generally made to be small, lightweight, and capable of accessing any channel within the specified band, not just a subset of assigned channels.

Military

Military organizations use handheld radios for a variety of purposes. Modern units such as the AN/PRC-148 Multiband Inter/Intra Team Radio (MBITR) can communicate on a variety of bands and modulation schemes and include encryption capabilities.

Amateur radio

Walkie-talkies (also known as HTs or "handheld transceivers") are widely used among amateur radio operators. While converted commercial gear by companies such as Motorola are not uncommon, many companies such as Yaesu, Icom, and Kenwood design models specifically for amateur use. While superficially similar to commercial and personal units (including such things as CTCSS and DCS squelch functions, used primarily to activate amateur radio repeaters), amateur gear usually has a number of features that are not common to other gear, including:

- Wide-band receivers, often including radio scanner functionality, for listening to non-amateur radio bands.

- Multiple bands; while some operate only on specific bands such as 2 meters or 70 cm, others support several UHF and VHF amateur allocations available to the user.

- Since amateur allocations usually are not channelized, the user can dial in any frequency desired in the authorized band.

- Multiple modulation schemes: a few amateur HTs may allow modulation modes other than FM, including AM, SSB, and CW,[5][6] and digital modes such as radioteletype or PSK31. Some may have TNCs built in to support packet radio data transmission without additional hardware.

A newer addition to the Amateur Radio service is Digital Smart Technology for Amateur Radio or D-STAR. Handheld radios with this technology have several advanced features, including narrower bandwidth, simultaneous voice and messaging, GPS position reporting, and callsign routed radio calls over a wide ranging international network.

As mentioned, commercial walkie-talkies can sometimes be reprogrammed to operate on amateur frequencies. Amateur radio operators may do this for cost reasons or due to a perception that commercial gear is more solidly constructed or better designed than purpose-built amateur gear.

Personal use

The personal walkie-talkie has become popular also because of the U.S. Family Radio Service (FRS) and similar unlicensed services (such as Europe's PMR446 and Australia's UHF CB) in other countries. While FRS walkie-talkies are also sometimes used as toys because mass-production makes them low cost, they have proper superheterodyne receivers and are a useful communication tool for both business and personal use. The boom in unlicensed transceivers has, however, been a source of frustration to users of licensed services that are sometimes interfered with. For example, FRS and GMRS overlap in the United States, resulting in substantial pirate use of the GMRS frequencies. Use of the GMRS frequencies (USA) requires a license; however most users either disregard this requirement or are unaware. Canada reallocated frequencies for unlicensed use due to heavy interference from US GMRS users. The European PMR446 channels fall in the middle of a United States UHF amateur allocation, and the US FRS channels interfere with public safety communications in the United Kingdom. Designs for personal walkie-talkies are in any case tightly regulated, generally requiring non-removable antennas (with a few exceptions such as CB radio and the United States MURS allocation) and forbidding modified radios.

Most personal walkie-talkies sold are designed to operate in UHF allocations, and are designed to be very compact, with buttons for changing channels and other settings on the face of the radio and a short, fixed antenna. Most such units are made of heavy, often brightly colored plastic, though some more expensive units have ruggedized metal or plastic cases. Commercial-grade radios are often designed to be used on allocations such as GMRS or MURS (the latter of which has had very little readily available purpose-built equipment). In addition, CB walkie-talkies are available, but less popular due to the propagation characteristics of the 27 MHz band and the general bulkiness of the gear involved.

Personal walkie-talkies are generally designed to give easy access to all available channels (and, if supplied, squelch codes) within the device's specified allocation.

Personal two-way radios are also sometimes combined with other electronic devices; Garmin's Rino series combine a GPS receiver in the same package as an FRS/GMRS walkie-talkie (allowing Rino users to transmit digital location data to each other) Some personal radios also include receivers for AM and FM broadcast radio and, where applicable, NOAA Weather Radio and similar systems broadcasting on the same frequencies. Some designs also allow the sending of text messages and pictures between similarly equipped units.

While jobsite and government radios are often rated in power output, consumer radios are frequently and controversially rated in mile or kilometer ratings. Because of the line of sight propagation of UHF signals, experienced users consider such ratings to be wildly exaggerated, and some manufacturers have begun printing range ratings on the package based on terrain as opposed to simple power output.

While the bulk of personal walkie-talkie traffic is in the 27 MHz and 400-500 MHz area of the UHF spectrum, there are some units that use the "Part 15" 49 MHz band (shared with cordless phones, baby monitors, and similar devices) as well as the "Part 15" 900 MHz band; in the US at least, units in these bands do not require licenses as long as they adhere to FCC Part 15 power output rules. A company called TriSquare is, as of July 2007, marketing a series of walkie-talkies in the United States based on frequency-hopping spread spectrum technology operating in this frequency range under the name eXRS (eXtreme Radio Service—despite the name, a proprietary design, not an official allocation of the US FCC). The spread-spectrum scheme used in eXRS radios allows up to 10 billion virtual "channels" and ensures private communications between two or more units.

Recreation

Low-power versions, exempt from licence requirements, are also popular children's toys such as the Fisher Price Walkie-Talkie for children illustrated in the top image on the right. Prior to the change of CB radio from licensed to "permitted by part" (FCC rules Part 95) status, the typical toy walkie-talkie available in North America was limited to 100 milliwatts of power on transmit and using one or two crystal-controlled channels in the 27 MHz citizens' band using amplitude modulation (AM) only. Later toy walkie-talkies operated in the 49 MHz band, some with frequency modulation (FM), shared with cordless phones and baby monitors. The lowest cost devices are very simple electronically (single-frequency, crystal-controlled, generally based on a simple discrete transistor circuit where "grownup" walkie-talkies use chips), may employ superregenerative receivers, and may lack even a volume control, but they may nevertheless be elaborately decorated, often superficially resembling more "grown-up" radios such as FRS or public safety gear. Unlike more costly units, low-cost toy walkie-talkies may not have separate microphones and speakers; the receiver's speaker sometimes doubles as a microphone while in transmit mode.

An unusual feature, common on children's walkie-talkies but seldom available otherwise even on amateur models, is a "code key", that is, a button allowing the operator to transmit Morse code or similar tones to another walkie-talkie operating on the same frequency. Generally the operator depresses the PTT button and taps out a message using a Morse Code crib sheet attached as a sticker to the radio; however, as Morse Code has fallen out of wide use outside amateur radio circles, some such units either have a grossly simplified code label or no longer provide a sticker at all.

In addition, personal UHF radios will sometimes be bought and used as toys, though they are not generally explicitly marketed as such (but see Hasbro's ChatNow line, which transmits both voice and digital data on the FRS band).

Smartphone Apps

A variety of mobile apps exist that mimic a walkie-talkie style interaction. They are marketed as low-latency, asynchronous communication. The advantages touted over two-way voice calls include: the asynchronous nature not requiring full user interaction (like SMS) and it is voice over IP (VOIP) so it does not use minutes on a cellular plan. Applications on the market that offer this walkie-talkie style interaction for audio include Voxer, Zello, and HeyTell, among others.[7] An application that offers this style of interaction for video is Glide.[8]

Specialized uses

In addition to land mobile use, walkie-talkie designs are also used for marine VHF and aviation communications, especially on smaller boats and ultralight aircraft where mounting a fixed radio might be impractical or expensive. Often such units will have switches to provide quick access to emergency and information channels.

Intrinsically safe walkie-talkies are often required in heavy industrial settings where the radio may be used around flammable vapors. This designation means that the knobs and switches in the radio are engineered to avoid producing sparks as they are operated.

Accessories

There are various accessories available for walkie talkies such as rechargeable batteries, drop in rechargers, multi-unit rechargers for charging as many as six units at a time, and an audio accessory jack that can be used for headsets or speaker microphones.[9]

When headsets are used with voice activation (VOX) capability the user can talk with hands free operation. Several types of audio accessories are available such as speaker microphones that clip near the ear, security type earpieces with a pendant push-to-talk switch and a built-in microphone, a headset or earbuds with a push-to-talk switch, or a single-ear lightweight behind-the-head headset with boom microphone and pendant push-to-talk switch similar to that worn by a telephone operator.[citation needed]

See also

- AN/PRC-6

- MOTO Talk

- Push to talk

- Signal Corps Radio

- Survival radio

- Two-way radio

- Vehicular communication systems

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Wolinsky, Howard (2003-09-25). "Riding Radio Waves For 75 Years, Motorola Milestones". Chicago Sun Times. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ "Al Gross". Lemelson-MIT Program. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ http://www.telecomhall.ca/tour/inventors/2006/donald_l_hings/WalkieTalkie.pdf?sourceid=navclient&ie=UTF-8&rls=GGLJ,GGLJ:2006-10,GGLJ:en&q=Donald+L.+Hings+. THE VANCOUVER SUN, Friday August 17, 2001 Walkie-Talkie Inventor Receives Order of Canada

- ↑ "CBC.ca - The Greatest Canadian Invention". CBC News.

- ↑ http://www.rigpix.com/tokyohypower/ht750.htm Tokyo HyPower HT750

- ↑ http://www.rigpix.com/mizuho/mizuho_mx2.htm Mizuho MX2

- ↑ Pogue, David (5 September 2012). "Smartphone? Presto! 2-Way Radio". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ Velazco, Chris. "Glide Rolls Out The Beta Version Of Its Video Messaging Android App At Disrupt NY". TechCrunch. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ↑ "Two Way Radios" page of IntercomsOnline.com.

Notations

- Onslow, David. "Two-Way Radio Success: How to Choose Two-Way Radios, Commercial Intercoms, and Other Wireless Communication Devices for Your Business". IntercomsOnline.com. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

Further reading

- Dunlap, Orrin E., Jr. Marconi: The man and his wireless. (Arno Press., New York: 1971)

- Harlow, Alvin F., Old Waves and New Wires: The History of the Telegraph, Telephone, and Wireless. (Appleton-Century Co., New York: 1936)

- Herrick, Clyde N., Radio: Theory and Servicing. (Reston Publishing Company, Inc., Virginia 1975)

- Martin, James. Future Developments in Telecommunications 2nd Ed., (Prentice Hall Inc., New Jersey: 1977)

- Martin, James. The Wired Society. (Prentice Hall Inc., New Jersey: 1978)

- Silver, H. Ward. Two-Way Radios and Scanners for Dummies. (Wiley Publishing, Hoboken, NH, 2005, ISBN 978-0-7645-9582-0)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Walkie-talkie. |

| Look up walkie-talkie in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- SCR-300-A Technical Manual

- U.S. Army Signal Corp Museum - exhibits and collections

- Al Gross, 2000 Lemelson-MIT Lifetime Achievement Award Winner, developed the "walkie-talkie".

- RetroCom, a collection of vintage radio gear images and articles.

- Simple VHF walkie-talkie circuit (note: requires an experienced builder, and may be illegal to operate without a proper license from your local communications agency)

| ||||||||||||||||||||