Wöhler synthesis

The Wöhler synthesis is the conversion of ammonium cyanate into urea. This chemical reaction was discovered in 1828 by Friedrich Wöhler in an attempt to synthesize ammonium cyanate. It is considered the starting point of modern organic chemistry. Although the Wöhler reaction concerns the conversion of ammonium cyanate, this salt appears only as an (unstable) intermediate. Wöhler demonstrated the reaction in his original publication with different sets of reactants: a combination of cyanic acid and ammonia, a combination of silver cyanate and ammonium chloride, a combination of lead cyanate and ammonia and finally from a combination of mercury cyanate and cyanatic ammonia (which is again cyanic acid with ammonia).

The reaction can be demonstrated by starting with solutions of potassium cyanate and ammonium chloride which are mixed, heated and cooled again. An additional proof of the chemical transformation is obtained by adding a solution of oxalic acid which forms urea oxalate as a white precipitate.

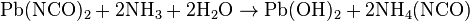

Alternatively the reaction can be carried out with lead cyanate and ammonia. The actual reaction taking place is a double displacement reaction to form ammonium cyanate:

Ammonium cyanate decomposes to ammonia and cyanic acid which in turn react to produce urea in a nucleophilic addition followed by tautomeric isomerization:

Complexation with oxalic acid helps drive this chemical equilibrium to completion.

The Wöhler synthesis is of great historical significance because for the first time an organic compound was produced from inorganic reactants. This finding went against the mainstream theory of that time called vitalism which stated that organic matter possessed a special force or vital force inherent to all things living. For this reason a sharp boundary existed between organic and inorganic compounds. Urea was discovered in 1799 and could until then only be obtained from biological sources such as urine. Wöhler reported to his mentor Berzelius

"I cannot, so to say, hold my chemical water and must tell you that I can make urea without thereby needing to have kidneys, or anyhow, an animal, be it human or dog".

It is argued that organic chemistry did not actually start with this discovery in 1828 but 4 years earlier with the synthesis of oxalic acid in 1824 also by Wöhler and also from the inorganic precursor cyanogen. It is also argued that vitalism was not put to bed either in 1828. His contemporaries Liebig and Pasteur never abandoned vitalism and it took until 1845 when Kolbe repeated an inorganic – organic conversion of carbon disulfide to acetic acid before vitalism started to lose supporters in serious numbers.

References

- ^ Friedrich Wöhler (1828). "Ueber künstliche Bildung des Harnstoffs". Annalen der Physik und Chemie 88 (2): 253–256. Bibcode:1828AnP....88..253W. doi:10.1002/andp.18280880206.

- ^ Wöhler's Synthesis of Urea: How Do the Textbooks Report It? Paul S. Cohen, Stephen M. Cohen J. Chem. Educ. 1996 73 883 Abstract

- ^ A Demonstration of Wöhler's Experiment: Preparation of Urea from Ammonium Chloride and Potassium Cyanate Zoltán Tóth. J. Chem. Educ. 1996 73 539. Abstract

- ^ Recreation of Wöhler's Synthesis of Urea: An Undergraduate Organic Laboratory Exercise James D. Batchelor, Everett E. Carpenter, Grant N. Holder, Cassandra T. Eagle, Jon Fielder, Jared Cummings The Chemical Educator 1/Vol .3,NO.6 1998 ISSN 1430-4171 Online article

- P. Walden (1928). "Die Bedeutung der Wöhlerschen Harnstoff-Synthese". Naturwissenschaften 16 (45–47): 835–849. Bibcode:1928NW.....16..835W. doi:10.1007/BF01451626.