Voalavo

- This article is about the genus Voalavo. See Nesomyinae for other Madagascar rodents (also known as "voalavo" in Malagasy).

| Voalavo | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Nesomyidae |

| Subfamily: | Nesomyinae |

| Genus: | Voalavo Carleton and Goodman, 1998 |

| Type species | |

| Voalavo gymnocaudus Carleton and Goodman, 1998 | |

| Species | |

| |

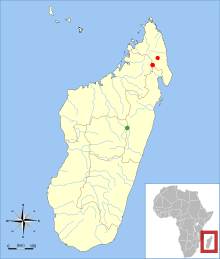

| Known localities of Voalavo gymnocaudus (red) and Voalavo antsahabensis (green) | |

Voalavo is a genus of rodent in the subfamily Nesomyinae, found only in Madagascar. Two species are known, both of which occur in mountain forest above 1250 m (4100 ft) altitude; Voalavo gymnocaudus lives in northern Madagascar and Voalavo antsahabensis is restricted to a small area in the central part of the island. The genus was discovered in 1994 and formally described in 1998. Within Nesomyinae, it is most closely related to the genus Eliurus, and DNA sequence data suggest that the current definitions of these two genera need to be changed.

Species of Voalavo are small, gray, mouse-like rodents, among the smallest nesomyines. They lack the distinctive tuft of long hairs on the tail that is characteristic of Eliurus. The tail is long and females have six mammae. In Voalavo, there are two glands on the chest (absent in Eliurus) that produce a sweet-smelling musk in breeding males. In the skull, the facial skeleton is long and the braincase is smooth. The incisive foramina (openings in the front part of the palate) are long and the bony palate itself is smooth. The molars are somewhat hypsodont (high-crowned), though less so than in Eliurus, and the third molars are reduced in size and complexity.

Taxonomy

A specimen of the genus was first collected in 1994 in Anjanaharibe-Sud, northern Madagascar. The genus was named Voalavo in 1998 by Michael Carleton and Steven Goodman, with a single species, the type Voalavo gymnocaudus, restricted to the Northern Highlands of Madagascar.[1] The generic name Voalavo is a Malagasy word for "rodent".[2] A second species, Voalavo antsahabensis, was named by Goodman and colleagues in 2005 from the region of Anjozorobe in the Central Highlands.[3] The two Voalavo species are closely related and quite similar, but differ in various subtle morphological characters (mainly measurements) and by 10% in the sequence of the mitochondrial gene cytochrome b.[4]

Voalavo is part of the subfamily Nesomyinae, which includes nine genera that are all restricted to Madagascar. Before the discoveries of Monticolomys (published in 1996) and Voalavo (1998), all of the known genera within Nesomyinae were quite distinct from each other, so much so that phylogenetic relationships among them long remained obscure. Like Monticolomys (closely related to Macrotarsomys), however, Voalavo shows clear similarities to another nesomyine genus, Eliurus.[5] In their description of Voalavo, Carleton and Goodman argued that, although closely related, Eliurus and Voalavo form separate monophyletic groups;[6] but a 1999 molecular phylogenetic study by Sharon Jansa and colleagues, who compared cytochrome b sequences among nesomyines and other rodents, found that Voalavo gymnocaudus was more closely related to Eliurus grandidieri than to other species of Eliurus. This finding called into question the separate generic status of Voalavo. However, tissue samples of Eliurus petteri, a species that is thought to be closely related to E. grandidieri, were not available, so this species could not be included in the study.[7] Data from nuclear genes also supports the relationship between V. gymnocaudus and E. grandidieri, but E. petteri remains genetically unstudied and the taxonomic issue has not been resolved.[8]

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of nuclear DNA supports a close relationship between Eliurus, Voalavo, and two other nesomyine genera, Gymnuromys and Brachytarsomys. These genera are more distantly related to the other nesomyine genera and even more distantly to the other subfamilies of the family Nesomyidae, which occur in mainland Africa.[9]

Description

| Locality | n | Head-body | Tail | Hindfoot | Ear | Mass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anjanaharibe-Sud (V. gymnocaudus) | 4 | 86–90 | 119–120 | 20–21 | – | 20.5–23.5 |

| Marojejy (V. gymnocaudus) | 5 | 80–90 | 113–126 | 17–20 | 15–15 | 17.0–25.5 |

| Anjozorobe (V. antsahabensis) | 4 | 86–91 | 106–119 | 19–21 | 15–16 | 20.7–22.6 |

| n: Number of specimens measured. All measurements are in millimeters, except body mass in grams. | ||||||

Voalavo is a small rodent resembling a mouse with gray fur.[11] Species of the genus are among the smallest known nesomyines, close in size only to Monticolomys koopmani.[12] In terms of external morphology, Voalavo is barely different from Eliurus; fur coloration patterns, general morphology of the feet, and number of mammae (six) are all the same in both genera. However, all species of Eliurus have a pronounced tuft of elongated hairs at the tip of the tail, a feature that is absent in Voalavo, although the latter does have slightly longer hairs near the tip. The tail is longer than the head and body. Relative tail length in V. gymnocaudus (136% of head and body length) is comparable to that of the longest-tailed species of Eliurus, E. grandidieri and E. petteri,[2] but V. antsahabensis has a somewhat shorter tail.[13] Furthermore, the pads of the feet are larger in Eliurus, and specifically, the thenar pad (located at the middle of the tarsus) is circular and fairly small in Voalavo, but longer and larger in Eliurus.[2] On the chest, Voalavo species have a gland that produces a sweet-swelling musk in breeding males; this gland is absent in Eliurus.[14] Unlike all other nesomyines but Brachyuromys, Voalavo lacks an entepicondylar foramen, an opening on the humerus (upper arm bone).[15]

The skull of Voalavo also resembles that of Eliurus, with a long facial skeleton, an hourglass-shaped interorbital region (between the eyes), and a smooth interorbital region and braincase, without ridges or shelves.[2] Other shared characteristics include an essentially featureless bony palate, without many pits and ridges, and a broad mesopterygoid fossa (the opening behind the palate). In other characteristics, Voalavo resembles some but not all species of Eliurus. For example, the length of the incisive foramina matches the maximum seen in Eliurus species (in this case, in Eliurus majori and Eliurus penicillatus).[16] The back margin of the incisive foramen is rounded in V. antsahabensis, but angular in V. gymnocaudus.[17] The two species also differ in the shape of the suture (dividing line) between the maxillary and palatine bones, which is straight in V. antsahabensis, but more curved in V. gymnocaudus.[18] The capsular process, a projection at the back of the mandible (lower jaw) that houses the root of the lower incisor, is indistinct in Voalavo, a feature it shares with E. grandidieri, E. majori, and E. petteri, but not the other species of Eliurus.[16]

Other features of the skull distinguish the two genera. The tegmen tympani, the roof of the tympanic cavity, is much reduced in Voalavo relative to Eliurus. The subsquamosal fenestrae, openings in the squamosal bone at the back of the skull, are larger in Voalavo than in Eliurus. The zygomatic plate, a plate at the sides of the skull that roots the front part of the zygomatic arches (cheekbones), is narrower in Voalavo, and lacks a clear zygomatic notch (a notch formed by a projection at the front of the zygomatic plate), which is present in Eliurus.[16] Among nesomyines, only Brachytarsomys has a more reduced zygomatic notch.[19]

Like Eliurus, Voalavo has moderately high-crowned (hypsodont) molars[20] with crowns that consist not of discrete cusps, but of transverse laminae (plates) that generally lack longitudinal connections.[21] However, Eliurus molars are slightly more hypsodont than those of Voalavo. The third upper and lower molars are smaller relative to the second molars in Voalavo than in Eliurus. Perhaps as a consequence, the upper third molar lacks discrete laminae in Voalavo, and the lower third molar has only two laminae (three in Eliurus).[22] There are three roots under each upper molar and two under each lower.[21]

Distribution and ecology

Both species of Voalavo occur in montane forest. V. gymnocaudus is restricted to the Northern Highlands, where it is found at 1,250–1,950 m (4,100–6,400 ft) altitude in Marojejy and Anjanaharibe-Sud.[23] The known range of V. antsahabensis is restricted to the vicinity of Anjozorobe at 1,250–1,425 m (4,101–4,675 ft) altitude.[24] Although most of the 450 km (280 mi) between the ranges of the two species consists of montane forest—suitable habitat for Voalavo—the area is bisected by the low-lying Mandritsara Window, which may serve as a barrier between the two species.[25] Subfossil remains of Voalavo have been found in the former Mahajanga Province (northwestern Madagascar).[26]

Very little is known of the ecology of Voalavo antsahabensis,[18] but V. gymnocaudus is thought to be largely terrestrial with some scansorial (tree-climbing) abilities.[27] It is active during the night, bears up to three young per litter, and probably eats fruits and seeds.[28] Various parasites have been recorded on V. gymnocaudus, including mites and Eimeria.[29]

Conservation status

Because Voalavo antsahabensis has a small range that is threatened by the practice of slash-and-burn agriculture (known in Madagascar as tavy), it is listed on the IUCN Red List as "Endangered".[24] Although V. gymnocaudus also has a small range, it is mostly within protected areas, and this species is therefore listed as "Least Concern".[30]

References

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 1998, pp. 164, 182.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Carleton & Goodman 1998, p. 189.

- ↑ Goodman et al. 2005, p. 168.

- ↑ Goodman et al. 2005, pp. 870–872.

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 1998, p. 193.

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 1998, pp. 193–195.

- ↑ Jansa, Goodman & Tucker 1999, p. 262.

- ↑ Jansa & Carleton 2003, pp. 1263–1264; Carleton & Goodman 2007, p. 17.

- ↑ Jansa & Weksler 2004, pp. 268–269, fig. 1; Musser & Carleton 2005, p. 930.

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 1998, table 11-7; Carleton & Goodman 2000, table 12-5; Goodman et al. 2005, table 1.

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 1998, p. 182.

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 1998, pp. 182, 189; Goodman et al. 2005, p. 865.

- ↑ Goodman et al. 2005, p. 868.

- ↑ Goodman et al. 2005, p. 866.

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 1998, p. 20.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Carleton & Goodman 1998, p. 190.

- ↑ Goodman et al. 2005, p. 869.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Goodman et al. 2005, p. 870.

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 1998, pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 1998, p. 191.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Carleton & Goodman 1998, p. 192.

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 1998, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Musser & Carleton 2005, p. 953.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Goodman 2009.

- ↑ Goodman et al. 2005, p. 872.

- ↑ Mein et al. 2010, p. 105.

- ↑ Carleton & Goodman 2000, p. 251.

- ↑ Goodman, Ganzhorn & Rakotondravony 2003, table 13.4.

- ↑ OConnor 1998, p. 76; OConnor 2000, p. 140; Laakkonen & Goodman 2003, p. 1196.

- ↑ Goodman 2008.

Literature cited

- Carleton, M.D.; Goodman, S.M. (1998). "New taxa of nesomyine rodents (Muroidea: Muridae) from Madagascar's northern highlands, with taxonomic comments on previously described forms". Fieldiana Zoology 90: 163–200.

- Carleton, M.D.; Goodman, S.M. (2000). "Rodents of the Parc national de Marojejy, Madagascar". Fieldiana Zoology 97: 231–263.

- Carleton, M.D.; Goodman, S.M. (2007). "A new species of the Eliurus majori complex (Rodentia: Muroidea: Nesomyidae) from south-central Madagascar, with remarks on emergent species groupings in the genus Eliurus". American Museum Novitates 3547: 1–21. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2007)3547[1:ANSOTE]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/5834.

- Goodman, S. (2008). "Voalavo gymnocaudus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- Goodman, S. (2009). "Voalavo antsahabensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- Goodman, S.M.; Ganzhorn, J.U.; Rakotondravony, D. (2003). "Introduction to the mammals". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. The Natural History of Madagascar. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 1159–1186. ISBN 978-0-226-30307-9.

- Goodman, S.M.; Rakotondravony, D.; Randriamanantsoa, H.N.; Rakotomalala-Razanahoera, M. (2005). "A new species of rodent from the montane forest of central eastern Madagascar (Muridae: Nesomyinae: Voalavo)". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 118 (4): 863–873. doi:10.2988/0006-324X(2005)118[863:ANSORF]2.0.CO;2.

- Jansa, S.A.; Carleton, M.D. (2003). "Systematics and phylogenetics of Madagascar's native rodents". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. The Natural History of Madagascar. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 1257–1265. ISBN 978-0-226-30307-9.

- Jansa, S.A.; Weksler, M. (2004). "Phylogeny of muroid rodents: relationships within and among major lineages as determined by IRBP gene sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 31 (1): 256–276. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.002. PMID 15019624.

- Jansa, S.A.; Goodman, S.M.; Tucker, P.K. (1999). "Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of the native rodents of Madagascar (Muridae: Nesomyinae): A test of the single-origin hypothesis". Cladistics 15 (3): 253–270. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1999.tb00267.x.

- Laakkonen, J.; Goodman, S.M. (2003). "Endoparasites of Malagasy mammals". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. The Natural History of Madagascar. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 1194–1198. ISBN 978-0-226-30307-9.

- Mein, P.; Sénégas, F.; Gommery, D.; Ramanivosoa, B.; Randrianantenaina, H.; Kerloc'h, P. (2010). "Nouvelles espèces subfossiles de rongeurs du Nord-Ouest de Madagascar". Comptes Rendus Palevol (in French) 9 (3): 101–112. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2010.03.002.

- Musser, G.G.; Carleton, M.D. (2005). "Superfamily Muroidea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 894–1531. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0.

- OConnor, B.M. (1998). "Parasitic and commensal arthropods of some birds and mammals of the Réserve Spéciale d'Anjanaharibe-Sud, Madagascar". Fieldiana Zoology 90: 73–78.

- OConnor, B.M. (2000). "Parasitic and commensal arthropods of some birds and mammals of Parc National de Marojejy, Madagascar". Fieldiana Zoology 97: 137–141.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||