Virtual temperature

In atmospheric thermodynamics, the virtual temperature  of a moist air parcel is the temperature at which a theoretical dry air parcel would have a total pressure and density equal to the moist parcel of air.[1]

of a moist air parcel is the temperature at which a theoretical dry air parcel would have a total pressure and density equal to the moist parcel of air.[1]

Introduction

Description

In atmospheric thermodynamic processes, it is often useful to assume air parcels behave approximately adiabatic, and thus approximately ideally. The gas constant for the standardized mass of one kilogram of a particular gas is dynamic, and described mathematically as:

where  is the universal gas constant and

is the universal gas constant and  is the apparent molecular weight of gas

is the apparent molecular weight of gas  . The apparent molecular weight of a theoretical moist parcel in Earth's atmosphere can be defined in components of dry and moist air as:

. The apparent molecular weight of a theoretical moist parcel in Earth's atmosphere can be defined in components of dry and moist air as:

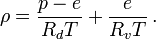

with  water vapor pressure,

water vapor pressure,  dry air pressure, and

dry air pressure, and  and

and  representing the molecular weight of water and dry air respectively. The total pressure

representing the molecular weight of water and dry air respectively. The total pressure  is described by Dalton's Law of Partial Pressures:

is described by Dalton's Law of Partial Pressures:

Purpose

Rather than carry out these calculations, it is convenient to scale another quantity within the ideal gas law to equate the pressure and density of a dry parcel to a moist parcel. The only variable quantity of the ideal gas law independent of density and pressure is temperature. This scaled quantity is known as virtual temperature, and it allows for the use of the dry-air equation of state for moist air.[2] Temperature has an inverse proportionality to density. Thus, analytically, a higher vapor pressure would yield a lower density, which should yield a higher virtual temperature in turn.

Derivation

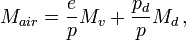

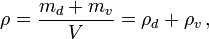

Consider an air parcel containing masses  and

and  of water vapor in a given volume

of water vapor in a given volume  . The density is given by:

. The density is given by:

where  and

and  are the densities of dry air and water vapor would respectively have when occupying the volume of the air parcel. Rearranging the standard ideal gas equation with these variables gives:

are the densities of dry air and water vapor would respectively have when occupying the volume of the air parcel. Rearranging the standard ideal gas equation with these variables gives:

and

and

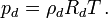

Solving for the densities in each equation and combining with the law of partial pressures yields:

Then, solving for  and using

and using  is approximately 0.622 in Earth's atmosphere:

is approximately 0.622 in Earth's atmosphere:

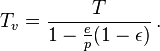

where the virtual temperature  is:

is:

We now have a non-linear scalar for temperature dependent purely on the unitless value  allowing for varying amounts of water vapor in an air parcel. This virtual temperature

allowing for varying amounts of water vapor in an air parcel. This virtual temperature  in units of Kelvin can be used seamlessly in any thermodynamic equation necessitating it.

in units of Kelvin can be used seamlessly in any thermodynamic equation necessitating it.

Variations

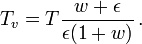

Often the more easily accessible atmospheric parameter is the mixing ratio  . Through expansion upon the definition of vapor pressure in the law of partial pressures as presented above and the definition of mixing ratio:

. Through expansion upon the definition of vapor pressure in the law of partial pressures as presented above and the definition of mixing ratio:

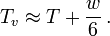

which allows:

Algebraic expansion of that equation, ignoring higher orders of  due to its typical order in Earth's atmosphere of

due to its typical order in Earth's atmosphere of  , and substituting

, and substituting  with its constant value yields the linear approximation:

with its constant value yields the linear approximation:

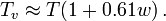

An approximate conversion using  in degrees Celsius and mixing ratio

in degrees Celsius and mixing ratio  in g/kg is:

in g/kg is:

Uses

Virtual temperature is used in adjusting CAPE soundings for assessing available convective potential energy from Skew-T log-P diagrams. The errors associated with ignoring virtual temperature correction for smaller CAPE values can be quite significant.[4] Thus, in the early stages of convective storm formation, a virtual temperature correction is significant in identifying the potential intensity in tropical cyclogenesis.[5]

Further reading

- Wallace, John M.; Hobbs, Peter V. (2006). Atmospheric Science. ISBN 0-12-732951-X.

References

- ↑ Bailey, Desmond T. (2 2000) [1987]. "Upper-air Monitoring". Meteorological Monitoring Guidance for Regulatory Modeling Applications. John Irwin. Research Triangle Park, NC: United States Environmental Protection Agency. pp. 9–14. EPA-454/R-99-005. Unknown parameter

|origmonth=ignored (help); - ↑ "AMS Glossary". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ↑ U.S. Air Force (1990) [1990]. The Use of the Skew-T Log p Diagram in Analysis and Forecasting. United States Air Force. pp. 4–9. AWS-TR79/006.

- ↑ "The Effect of Neglecting the Virtual Temperature Correction on CAPE calculations, Weather and Forecasting 1994; 9: 625-629". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ↑ "Tropical cyclone genesis potential index in climate models". International Research Institute for Climate and Society. Retrieved 2009-12-10.