Videodrome

| Videodrome | |

|---|---|

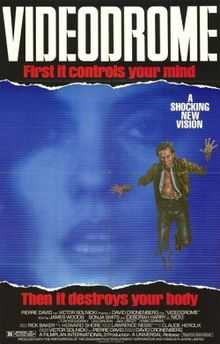

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Cronenberg |

| Produced by | Claude Héroux |

| Written by | David Cronenberg |

| Starring |

James Woods Sonja Smits Deborah Harry |

| Music by | Howard Shore |

| Cinematography | Mark Irwin |

| Editing by | Ronald Sanders |

| Studio | Canadian Film Development Corporation |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

| Release dates |

|

| Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.952 million |

| Box office | $2,120,439 |

Videodrome is a 1983 Canadian science fiction body horror film written and directed by David Cronenberg, starring James Woods, Sonja Smits, and Deborah Harry.

Set in Toronto in the early 1980s, it follows the CEO of a small television station who discovers a broadcast signal featuring extreme violence and torture. Layers of deception unfold as he uncovers the signal's source and loses touch with reality in a series of increasingly bizarre and violent hallucinations.

Plot

Max Renn (Woods) is the president of CIVIC-TV, a UHF television station in Toronto that specializes in sensationalistic programming. Displeased with his station's current lineup, Max is looking for something that will break through to a new audience. One morning, he is summoned to the clandestine office of Harlan (Peter Dvorsky), who operates CIVIC-TV's pirate satellite dish which can intercept international broadcasts. Harlan shows him Videodrome, a plotless show apparently being broadcast out of Malaysia which depicts the brutal torture and murder of anonymous victims in a reddish-orange chamber. Believing this to be the future of television—seemingly staged snuff TV—Max orders Harlan to begin pirating the program.

Appearing on a talk show, Max defends his station's programming choices to Nicki Brand (Harry), a sadomasochistic psychiatrist and radio host, and Professor Brian O'Blivion (Jack Creley), a pop culture analyst and philosopher who will only appear on television if his image is broadcast into the studio, onto a television, from a remote location. O'Blivion delivers a speech prophesying a future in which television supplants real life. Max dates Nicki, who is sexually aroused when he shows her an episode of Videodrome and coaxes him into having sex with her while they watch it.

Harlan tells Max that a signal delay which caused it to appear to be coming from Malaysia was a ploy by the broadcaster, and that Videodrome is being broadcast out of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Max informs Nicki, who excitedly goes to Pittsburgh to try and audition for the show under the guise of a business trip. When Nicki fails to return to Toronto, Max contacts Masha (Lynne Gorman), a softcore feminist pornographer with ties to the porn community, and asks her to help him find out the truth about Videodrome. Through Masha, Max learns that not only is the footage in Videodrome not faked, but it is the public "face" of a political movement. Masha further informs him that O'Blivion knows about Videodrome.

Max tracks down O'Blivion's office to a mission where homeless people are encouraged to engage in marathon sessions of television viewing. He discovers the mission is run by O'Blivion's daughter, Bianca (Sonja Smits), with the goal of helping to bring about her father's vision of a world in which television replaces every aspect of everyday life. Later, Max views a videotape in which O'Blivion informs him that the Videodrome "is a socio-political battleground in which a war is being fought for control of the minds of the people of North America".

Shortly thereafter, Max begins experiencing disturbing hallucinations in which his torso transforms into a gaping hole that functions as a VCR. Bianca tells him these are side-effects from having viewed Videodrome, which carries a malicious broadcast signal that causes the viewer to develop a malignant brain tumour. O'Blivion helped to create it as part of his vision for the future, but when he found out it was to be used for malevolent purposes, he attempted to stop his partners; they used his own invention to kill him. In the year before his death, O'Blivion recorded tens of thousands of videos, which now form the basis of his television appearances.

Max is contacted by Videodrome's producer, the Spectacular Optical Corporation, an eyeglasses company that acts as a front for a NATO weapons manufacturer. The head of Spectacular Optical, Barry Convex (Leslie Carlson), has been secretly working with Harlan to get Max exposed to Videodrome and to have him broadcast it, as part of a crypto-government conspiracy to morally and ideologically "purge" North America and fatal brain tumours to "lowlifes" fixated on extreme sex and violence. Convex then inserts a brainwashing video tape into the "VCR" in Max's torso. Under Convex's influence, Max murders his colleagues at CIVIC-TV, and later attempts to kill Bianca, as Videodrome considered these victims threats to its mission.

Bianca successfully "reprograms" him to turn against Videodrome, in the hope of destroying the project that led to her father's death. On her orders, Max kills Harlan, then tracks Convex to a trade show, where he shoots him to death in front of a horrified crowd. Afterwards, Max takes refuge on a derelict boat in an abandoned harbour, where Nicki appears to him on a TV set. She tells him he has weakened Videodrome, but in order to completely defeat it, he has to ascend to the next level and "leave the old flesh". The television then shows an image of Max shooting himself in the head, which causes the set to explode, splattering the deck of the ship with bloody human intestines. Imitating what he has just seen on TV, Max says "Long live the new flesh" and then shoots himself.

Cast

- James Woods as Max Renn. Woods' character was named after the Renn Max racing motorcycle. Renn means "race" in German. Director David Cronenberg was obsessed with motorcycles at the time. Cronenberg has described Max as "flippant" (especially in his responses on The Rena King Show).[1]

- Deborah Harry as Nikki Brand. Cronenberg said that the "Nikki" refers to the razor cuts, or nicks, on her back and the "Brand" refers to the moment when she brands herself with a cigarette burn to her breast.[1]

- Sonja Smits as Bianca O'Blivion

- Peter Dvorsky as Harlan

- Leslie Carlson as Barry Convex

- Jack Creley as Professor Brian O'Blivion. Professor O'Blivion was based on Marshall McLuhan. As a young man, Cronenberg attended the University of Toronto; first studying science, but eventually gaining his degree in Literature. McLuhan was a lecturer in media studies at the University during the same time (the early 1970s), and is often credited as an influence on Cronenberg's ideas for Videodrome. Cronenberg has described O'Blivion as "complex."[1]

- Reiner Schwarz as Moses. Before acting, Schwartz was a notable CHUM-FM DJ in the Toronto area.[1]

- David Tsubouchi as a Japanese porn dealer. Tsubouchi later became the Minister of Culture in the Ontario provincial government. His appearance in this controversial film as a pornographer was exploited by the opposition.[1]

David Cronenberg briefly stood in as Max Renn in one scene; according to Cronenberg, Woods was so scared to put on the pulsating device that Cronenberg took his place to get the shots where Max Renn is sitting down wearing the Image Accumulator.[1]

Production

Development

Writer/director David Cronenberg recalled how, when he was a child, he used to pick up television signals from Buffalo, New York, late at night after Canadian stations had gone off the air, and how he used to worry he might see something disturbing not meant for public consumption. This formed the basis for the plot of Videodrome.[1] Alternate titles for Videodrome were "Network of Blood" and "Zonekiller".[2][3][4]

Many of the story elements in Videodrome, in addition to the basic conceit, have some basis in writer/director Cronenberg's life. For example, "Civic TV" was based in part on CityTV, a Toronto television station which in the 1970s and early 1980s was notorious for broadcasting soft-core pornography, or "baby-blue films" as it was known, among its programming. One of Max's business partners is named Moses likely in reference to CityTV co-founder Moses Znaimer. Znaimer claimed that the character of Max Renn was based on him, but Cronenberg has denied this claim in his director's commentary of the film. The interview on The Rena King Show between Max Renn, Nikki Brand and Brian O'Blivion near the beginning of the film was based on a similar experience in Cronenberg's life. "The interview with Nikki Brand was also provoked in me by an interview I did with a woman who was very much like Nikki Brand, even though I never got to know her personally. On the show, she was very seductive and wore a red dress. She was very sexually provocative and I said some of the things to her that I have Max say to Nikki…" The Rena King Show itself was based on the Dini Petty interview show on CityTV.[1]

Origin of Videodrome

A deleted scene from the film provides background on the origin of Videodrome. In that scene Convex tells Max about the "Image Accumulator," (which is the device placed on Max's head during his meeting with Convex) an experimental new form of night vision that can work in zero-light conditions. When the developers played the recorded footage from the Accumulator, they saw things that could not have been there. They conclude these phantom figures were hallucinations of the test volunteers, inexplicably recorded by the Accumulator. Further research of the test volunteers revealed they had developed a brain tumour, which externalized their hallucinations, but more specifically, granted them reality warping abilities, which Max refers to as "brain damage". The same signal used in the Image Accumulator was then used to create Videodrome.[5]

Script

Cronenberg did not want to make any fragments of his first draft—titled "Network of Blood"—public. While writing his rough drafts, Cronenberg accepts as a given that they will resemble the final product in only the most basic way. In the first draft of Videodrome, Max Renn combats his hallucination by chopping his flesh gun off at the wrist, and from the stump there grows a fleshy, “potato masher”–style hand grenade, which explodes. There is a kissing scene in which Max and Nicki’s faces melt together into a single object that dribbles down, crawls across the floor and up the leg of an onlooker, and melts him. And the most horrible murder featured in the finished film—the erupting cancer death of Barry Convex—originally was to happen to five other characters as well. “My early drafts tend to get extreme in all kinds of ways: sexually, violently, and just in terms of weirdness,” Cronenberg explains. “But I have to balance this weirdness against what an audience will accept as reality. Even in the sound mix, when we’re talking about what sort of sound effects we want for the hand moving around inside the stomach slit, for example; we could get really weird and use really loud, slurpy, gurgly effects, but I’m playing it realistically. That is to say, I’m giving it the sound it would really have, which is not much. I’m presenting something that is outrageous and impossible, but I’m trying to convey it realistically.”[2]

Cronenberg’s producers—Pierre David, Victor Solnicki, and Claude Héroux—embraced the film's first draft. “The way Videodrome really started,” Cronenberg remembers, “was Pierre saying that he wanted to do another picture with me, and me reciprocating. I met with him in Montreal and told him, in just a few words, the basic plot; it was only the first part of the movie I described to him, and it sounded more like a thriller than anything, in that limited description, and he liked what I said. But when I started writing it and all of these other things started to leap out at me, I really thought they would reject it. What I was writing was so much more extreme than my premise had suggested. To my surprise, all three of them loved it! I can’t tell you how surprised I was, because I thought I’d been going nuts all alone in my little room. Claude, in fact, said that he liked it best of anything I’d written but that if we shot it as it was written, it’d get a triple X for sure. I told him I had written it in a more extreme fashion than I would want to see it on the screen myself.”[2]

Casting

The “wild” first draft of Videodrome was the script that got the production its major talent, including actors James Woods and Deborah Harry, special makeup effects artist Rick Baker and his EFX Inc. crew, and many other essential players.[2]

David Cronenberg approached Woods' agent for the film with the uncompleted script. "I think it was only 70 pages long," recalls Woods, "I remember meeting David first at the Beverly Hills Hotel in Beverly Hills, California, and I had read the 70 pages with no ending and thought it was pretty terrific."[6] "I was very excited to be working w/Jimmy [Woods]," noted Cronenberg, "who really embodied that kind of intensity and articulate inventive character that I had written in the script." Cronenberg added that Woods has a "lovely comic flair." Director of Photography Mark Irwin added, "When Jimmy got ahold of the character, and really motivated to do certain things, he really ran with it and David just stepped back."[1]

"It's always been my pleasure to find Canadian actors who have not done a lot of movie work," reflected Cronenberg, "but who are terrific actors and therefore are a kind of revelation on screen because people haven't seen them before. Peter Dvorsky was one of those. He done quite a bit of Canadian stuff that I'd seen, but I don't think he hadn't done much that had gone international. He was a real revelation as Harlan. He just had a wonderful texture, such sly way of underplaying, just a lovely voice. I didn't cast because he was a techno-nerd or anything like that."[1]

Cronenberg cast Deborah Harry as Nikki Brand. "Debbie, of course," adds Cronenberg, "was famous as a singer/performer. Her band was Blondie. And they were huge, they were really huge in their time. Not just as a band, but as a kind of essential part of the cultural zeitgeist of New York City. And she knew William Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg and was connected with everything that was going, especially in New York. A kind of above-ground/underground movement. But she was not an experienced actress at the time. We spent a lot of time discussing the difference between performing on stage which she was terrific at and performing for the camera which she was a neophyte at. But she was very responsive and very willing to learn and to understand that the kind of self-parody and satirical stuff that she did onstage simply did not work when she was trying to play a real character, a human being on screen."[1]

Principal photography

Filmplan International financed the film. "Filmplan. Film plan to take over the world," recalls Cronenberg, "Kind of ominous I always thought. Maybe more ominous than Videodrome."[1] Shooting for the film began on October 19, 1981.[2] "The fact that so many of us had worked with David," notes director of photography Mark Irwin, "and had also worked on documentaries and much lower-budget movies, it was easy to change and run fast. There was sort of an enthusiasm that had legs."[1] Production began with a toned down (and unfinished) second draft. Throughout the production schedule, Cronenberg wrote new scenes and rewrote old ones, and new sheets were distributed to crew members regularly. The writing of Videodrome continued up until the very last day of shooting, December 19. Additional makeup effects photography was done in March 1982; the need to shoot a revised climax brought the crew back to Toronto for two days in May; and further changes were effected in the editing room.[2]

Mark Irwin recalls modifying many locations to suit the purposes of the film. In the scene where Max meets the two Japanese salesmen in a hotel, a mirror was added to the white wall behind Max Renn. "I wish we could have rented more than just a hotel room," recalls Irwin, "Would have been nice to paint the wall, but, what can I say?"[1]

Irwin has said the big difficulty in shooting the film was shooting scenes with video screens in them. "The biggest stumbling block from my perspective shooting Videodrome was how to get these video images on the screen, because we were going to run real-time NTSC images and how do we get that without- because this was before we had any sync boxes, anything like that. We ended up shooting with a separate camera that had a fixed TV shutter in it and that seemed to be the best for eliminating any roll bars, any big roll bars, we had a pencil thin one that would move very slowly. All in all it was a challenge to balance things to the TV sets. And then the pumps and motors and all kinds of stuff causing interference."[1]

Irwin also had trouble finding the right way to light Deborah Harry's face: "She had a very- has a very interesting face. And the classic wraparound soft light was not going to work- or did not work with her, and by default I found out how to bring out the beauty in her […] She had two kind of furrows diagonally from either side of her nose. I couldn't get rid of the furrows." With a straight hard light, Irwin was able to get the look he wanted.[1]

Shooting monitor inserts

The first week was completely devoted to the videotaping of a variety of monitor inserts, including the monologues of Professor O’Blivion, a number of brutal torture sequences for the “Videodrome” program, as well as Samurai Dreams and Apollo & Dionysus, two soft-porn programs that are pitched by salespersons to Max Renn’s Civic TV and that were scripted to be shown in excerpt.[2] Cronenberg personally directed the two soft-porn programs because, "I wanted to have done it all. I didn't want someone else to..."[1] Cronenberg had worked with video before, making two episodes of the television program Peep Show, “The Victim” and “The Lie Chair,” in 1977 for the Canadian Broadcasting Company, but he felt some trepidation about working with it again. “I wasn’t looking forward to those sessions, I must say,” Cronenberg admits. “I’d done it before, but on two-inch tape and with multiple cameras, so we could edit as we were shooting by going from camera to camera. There wasn’t any of that on Videodrome. It’s very strange; I never really felt I got those scenes, this time, until we reshot them off monitors. Both [director of photography] Mark [Irwin] and I are very fascinated by videotape; it has a whole other feel. But I was much happier when we were back to shooting film.”[2]

Samurai Dreams was photographed in a rented corner of Toronto’s Global TV studios, on C-format one-inch tape, silent. “We shot it in half a day,” Irwin remembers, “and that’s where I came into the business—shooting porn [Ed Hunt’s Diary of a Sinner, 1974]—so I felt right at home. I told David that I hadn’t realized the Japanese were so raunchy, but he confessed that he’d made up all that Oriental ritualism surrounding the dildo. He’d had it carved the night before. The atmosphere on the set was very loose, very funny. The girl, who was French and spoke very little English, was very open to the whole thing, and there wasn’t any tension around to scare her away.” Asked about his striking ambiance, Irwin says, “Well, to see it on the set, it looked a lot flatter than it does on a monitor. Had I shot Samurai Dreams on film, I would have had about six lights turned off to create that scene.” Watching the short unreel on a handy VCR, Irwin refers to the misty exterior tracking camera move as “my Kurosawa shot.”[2]

Cronenberg recalls working with extras for the Videodrome torture shoots: "Most of the people we worked with enjoyed the experience, because it was cathartic. Of course, they weren't really being hurt and they were getting a lot more attention than an extra usually gets. We found - in one case - there was a woman who kept coming back. She kept visiting the set. She would dress up and put on a lot of makeup and dress herself really well and just kind of hang around. She couldn't let go of being tortured on the Videodrome set. It was quite strange, but very much in keeping with the strangeness of the film as a whole."[1]

Prosthetic effects

Videodrome used Betamax videotape cassettes because VHS videotape cassettes were too large to fit the faux abdominal wound.[1] The cancer that attacks Barry Convex was made out of Polyvinylchloride.[7]

Music

An original score was composed for Videodrome by Cronenberg's close friend, Howard Shore.[8] The score was composed to follow Max Renn's descent into video hallucinations, starting out with dramatic orchestral music that increasingly incorporates, and eventually emphasizes, electronic instrumentation. To achieve this, Shore composed the entire score for an orchestra before programming it into a Synclavier II digital synthesizer. The rendered score, taken from the Synclavier II, was then recorded being played in tandem with a small string section. The resulting sound was a subtle blend that often made it difficult to tell which sounds were real and which were synthesized.[9]

The music for the film plays over the Universal logo. "So right from the Universal Logo, you are already kind of unsettled," Cronenberg said, "That's because of Howard Shore's wonderful score for the movie, which was subversive and perverse and unsettling without being obvious."[1]

The soundtrack was also released on vinyl by Varèse Sarabande and was re-released on compact disc in 1998. The album itself is not just a straight copy of Howard Shore's score, but rather a remixing. Howard Shore has commented that while there were small issues with some of the acoustic numbers, that "on the whole I think they did very well."[9] The album is currently out of print.

Videodrome's cult film status has made it a popular source for sampling and homage in Electro-industrial, EBM, and heavy metal music. It ranked tenth on the Top 1,319 Sample Sources list of 2004.[10]

Censorship

Many shots of the film were cut from the film's theatrical release. For example, the shot of the dildo in Samurai Dreams was originally cut. "Censorship is always very personal," replied Cronenberg, "and has very much to do with the sensibility of the one who is being censorious."[1]

"It's interesting to see what people read into images when they are being censorious," added Cronenberg, "I was accused of having a scene where a man was being castrated. What was being done to him was bad enough, electrodes applied to the testicles. But it wasn't a scene of castration, despite what the MPAA thought it was. They made me cut it, or most of it."[1]

Reception

The film received generally positive reviews. Rotten Tomatoes gave the film a rating of 80% fresh based on 40 reviews, with the consensus "Visually audacious, disorienting, and just plain weird, Videodrome's musings on technology, entertainment, and politics still feel fresh today."[11] Metacritic gave the film a metascore of 60.[12] It has been described as a "disturbing techno-surrealist film"[13] and "burningly intense, chaotic, indelibly surreal, absolutely like nothing else".[14] Leonard Maltin gave the film two stars out of four, writing, "Genuinely intriguing story premise… Unfortunately, story gets slower—and sillier— as it goes along, with icky special effects by Rick Baker."[15] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film one and a half stars out of four, remarking, "The characters are bitter and hateful, the images are nauseating, and the ending is bleak enough that when the screen fades to black it's a relief… Videodrome, whatever its qualities, has got to be one of the least entertaining films of all time." In fairness, Ebert noted that the film could have worked because it had "basically a good idea for a screenplay" but failed due to being "relentlessly grim". [16][17]

Videodrome opened on February 4, 1983. It debuted at number 8 on the box office charts, grossing $1,194,175 on 600 theaters with an average theater gross of $1,990. The film's widest release was 600 theaters and was in release for 10 days. It was a box office bomb, grossing $2,120,439 on a budget of $5.952 million.[18]

Awards

Despite its poor commercial performance, Videodrome won a number of awards upon its release. At the 1984 Brussels International Festival of Fantasy Film, it tied with Bloodbath at the House of Death for Best Science-Fiction Film[19] and Mark Irwin received a CSC Award for Best Cinematography in a Theatrical Feature. Videodrome was also nominated for eight Genie Awards with David Cronenberg tying Bob Clark's A Christmas Story for Best Achievement in Direction.[19][20]

Legacy

Andy Warhol once described Videodrome as "A Clockwork Orange of the '80s".[21] In 2007, Videodrome scored fourth on Bravo TV's "30 Even Scarier Movie Moments". It was also selected as one of the 23 Weirdest Films of All Time by Total Film.[22] It was named the 89th most essential film in history by the Toronto International Film Festival.[23]

Videodrome is listed in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, one of three films by Cronenberg to be included in the book.[24][25][26] R. Barton Palmer writes, "A groundbreaking film of the commercial/independent movement of the 1980s Hollywood, David Cronenberg's story about the horrible transformations wrought by exposure to televised violence wittily thematizes the very problems that the director's exploration of violent sexual imagery in his previous productions had caused with censors, Hollywood distributors and feminist groups… Videodrome remains one of Hollywood's most unusual films, too shocking and idiosyncratic to be anything but a commercial failure."[24]

Writer/director Cronenberg would revisit similar subject matter in his 1999 sci-fi thriller eXistenZ.

Home video releases

Videodrome has been released twice on DVD, once in September 8, 1998 by Universal Pictures and again in August 31, 2004 by the Criterion Collection.

1998 Universal DVD release

Videodrome was released on September 8, 1998 by Universal Pictures. The running time is 89 minutes. The film is presented in letterbox 1.85:1 aspect ratio with audio in Dolby Digital Mono 2.0 in English and French. Special features included cast and filmmakers' biographies, theatrical trailers, theatrical text/photo galleries and production notes.[27] Bryant Frazer of Deep Focus gave the DVD release an "A+", one of eleven films to receive the website's highest rating.[28][29]

2004 Criterion Collection release

Videodrome was re-released in August 31, 2004 by the Criterion Collection.[30][31]

Novelization

A novelization of Videodrome was released by Zebra Books alongside the movie in 1983. Though credited to "Jack Martin," the novel was in fact the work of acclaimed horror novelist Dennis Etchison.[32][33] Cronenberg reportedly invited Etchison up to Toronto where they discussed and clarified the story, allowing the novel to remain as close as possible to the actions in the film. There are some notable differences however, such as the inclusion of the infamous "bathtub sequence", a scene never filmed in which a television rises from Max Renn's bathtub like a Venus in a conch shell.[34] This was the result of the lead time required to write the book, which left Etchison working with an earlier draft of the script than was used in the film. The book is currently out of print.

Remake

In 2009, Universal Studios announced that it had obtained the rights to produce a remake of Videodrome. Ehren Kruger was named to write the script and produce the film with partner Daniel Bobker. They had hoped for a release date in 2011. Kruger and Bobker planned to modernize the concept, infusing it with the possibilities of nano-technology and blow it up into a large-scale sci-fi action thriller.[35] On August 22, 2012, Universal Pictures announced that Adam Berg would make his directorial debut with the remake of Videodrome.[36]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 Cronenberg, David; Irwin, Mark (Spring/Winter 2004). David Cronenberg/Mark Irwin Commentary [Videdrome DVD; Audio Track 2]. Criterion Collection. Los Angeles, California; Toronto, Canada.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Lucas, Tim (August 30, 2004). "Medium Cruel: Reflections on Videodrome". Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2012-10-02. (Reprinted on pages 15-31 of the Videodrome Criterion Collection DVD booklet).

- ↑ "Videodrome". Understanding Media. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ "Videodrome: Visions of Excess". Archived from the original on 2006-04-26. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ "Unseen Videodrome". Cronendrome. Archived from the original on 2006-05-01. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ Harry, Deborah; Woods, James. Spring 2004. James Woods/Deborah Harry Commentary, Videodrome DVD; Audio Track 3. Criterion Collection. Los Angeles, California.

- ↑ Lucas, Tim (August 2, 2007). "Your Faithful Blogger on the VIDEODROME set". Tim Lucas Video Watchblog (Blogger). Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ Lucas 2008, p. 130.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lucas 2008, p. 133.

- ↑ "The Top 1319 Sample Sources". Archived from the original on 2004-09-01. Retrieved 2012-01-22. "10 (8) Videodrome".

- ↑ "Videodrome". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ↑ "Videodrome". Metacritic (CBS Interactive Inc.). Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ↑ Dinello, Daniel (2005). Technophobia!: science fiction visions of posthuman technology. University of Texas Press. p. 153. ISBN 0-292-70986-2.

- ↑ Beard, William; White, Jerry (2002). North of everything: English-Canadian cinema since 1980. University of Alberta. p. 153. ISBN 0-88864-390-X.

- ↑ Maltin, Leonard. (August 2008). "Videodrome"

. Leonard Maltin's 2009 Movie Guide (Paperback ed.). New York, NY: Penguin Group. p. 1493. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

. Leonard Maltin's 2009 Movie Guide (Paperback ed.). New York, NY: Penguin Group. p. 1493. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9. - ↑ Ebert 1987, p. 636.

- ↑ Ebert 1987, p. 637.

- ↑ "Videodrome". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 The David Cronenberg Picture Pages. SuperiorPics.com. Retrieved 2012-10-05.

- ↑ David Cronenberg: Selected Awards and Nominations. Foi Lorber. 1999. "1984- Genie Awards, Won Best Achievement in Direction, Videodrome"

- ↑ Ring, Robert C. (November 22, 2011). "Best of the Best". Sci-Fi Movie Freak (Paperback ed.). Krause Publications. p. 47. ISBN 978-1440228629.

- ↑ "Total Film's 23 Weirdest Films of All Time on Lists of Bests". Listsofbests.com. 2007-04-06. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ↑ "The Essential 100". Toronto International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 2010-08-08. Retrieved 2012-10-03. "89 VIDEODROME (David Cronenberg)".

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Klein & Palmer 2011, p. 690.

- ↑ Klein & Palmer 2011, p. 730.

- ↑ Klein & Palmer 2011, p. 798.

- ↑ "Videodrome DVD". CD Universe. Retrieved 2012-10-05. (This page is for the 1998 Universal DVD release).

- ↑ Frazer, Bryant (September 29, 1998). "Videodrome". Deep Focus. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ↑ "All A Grade". Deep Focus. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ↑ "Videodrome". Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

- ↑ "Videodrome DVD". CD Universe. Retrieved 2012-10-05. (This page is for the 2004 Criterion Collection DVD release).

- ↑ Etchison, Dennis (January 1983). Videodrome (Novelization of the screenplay by David Cronenberg). New York, New York: Zebra Books, Kensington Publishing Corp. ISBN 0821711660.

- ↑ "Bibliography: Videodrome". ISFDB. Retrieved 2012-10-05.

- ↑ Lucas 2008, p. 119.

- ↑ Fleming, Mike (April 26, 2009). "Universal to remake Videodrome". Variety. Retrieved 2012-10-05.

- ↑ Fleming, Mike (August 22, 2012). "Universal Sets Adam Berg To Helm ‘Videodrome’ Remake". Deadline New York. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

Bibliography

- Ebert, Roger (1987) [1983]. V. "Roger Ebert's Movie Companion - 1988 Edition". Chicago Sun-Times (Paperback, 3rd ed.) (Kansas City, Missouri: Andrews, McKeel & Parker). pp. 636–637. ASIN 0836262123. ISBN 978-0836262124.

- Lucas, Tim (2008). Studies in the Horror Film - Videodrome. China: Centipede Press. ISBN 1-933618-28-0.

- Klein, Joshua; Palmer, R. Barton (2011) [2003]. Schneider, Steven Jay, ed. 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die (Updated ed.). London, England: Quintessence Editions Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7641-6422-4. LCCN 2008926687. OCLC 223768961.

Further reading

- Bukatman, Scott (1993). "Terminal Identity: The Virtual Subject". Postmodern Science Fiction. Duke University Press.

- Grace, D. M. (2003). From Videodrome to Virtual Light: David Cronenberg and William Gibson. Extrapolation (44) 3. pp. 344–55.

- Hotchkiss, L. M. (Fall 2003). 'Still in the Game': Cybertransformations of the 'New Flesh' in David Cronenberg's eXistenZ. The Velvet Light Trap (52). pp. 15-32.

- Molitor, Stella (May 1984). Première (France). p. 15.

- Young, S. S.-F. (2002). 'Forget Baudrillard': The Horrors of 'Pleasure' and the Pleasures of 'Horror' in David Cronenberg's Videodrome. Cross Cultures (56). pp. 147-74.

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Videodrome |

- Videodrome at the Internet Movie Database

- Videodrome at allmovie

- Videodrome at Box Office Mojo

- Videodrome at Rotten Tomatoes

- Videodrome at the Criterion Collection

- Videodrome review at InternalBleeding

- understanding media - Videodrome, a list of academic texts about the film

| |||||