Vidal Santiago Díaz

| Vidal Santiago Díaz | |

|---|---|

| Born |

February 1, 1910 Aguas Buenas, Puerto Rico |

| Died |

March 1982 Bayamon, Puerto Rico |

Political party | Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

Political movement | Puerto Rican Independence movement |

|

Notes Santiago Díaz was Pedro Albizu Campo's barber | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

|---|

Flag of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

|

Events and Revolts |

|

Nationalist Leaders

|

Vidal Santiago Díaz [note 1] (February 1, 1910 – March 1982) was a member of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and served as president of the Santurce Municipal Board of officers of the party. He was also the personal barber of Nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos. Though not involved in the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party Revolts of the 1950s, Santiago Díaz was attacked at his barbershop by forty armed police officers and U.S. National Guardsmen because of his Puerto Rican independence ideals. The attack was historic in Puerto Rico – the first time an event of that magnitude had ever been transmitted live via radio, and heard all over the island.[1]

Early years

Santiago Díaz was born and raised in Aguas Buenas, Puerto Rico, where he received his formal education. He later moved to Santurce, a mostly working-class section of San Juan, where he became a professional barber. Santiago Díaz was greatly troubled by the inhumanity and violence of the Ponce Massacre.[2] After reflecting on this U.S.-sponsored police slaughter, and its moral implications, Santiago Díaz joined the Nationalist Party and became a follower of its president, Pedro Albizu Campos.

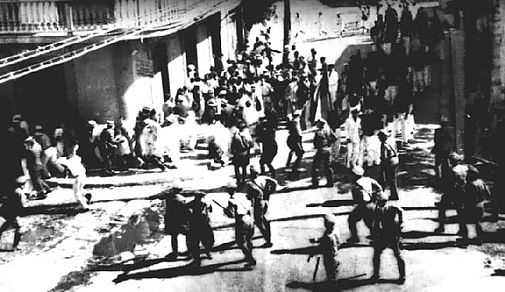

The Ponce Massacre

On Palm Sunday in March 21, 1937, the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party held a peaceful march in the city of Ponce, Puerto Rico. This march was meant to commemorate the ending of slavery in Puerto Rico by the governing Spanish National Assembly in 1873. It also protested the imprisonment by the U.S. government of Nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos, on charges of sedition.[3][4]

The innocent Palm Sunday March turned into a police slaughter. Both march participants and innocent bystanders were fired upon by the Insular Police, resulting in the death of 18 unarmed civilians and one policeman - every one from police fire as none of the civilians carried any firearms.[5] In addition, some 235 civilians were wounded, including women and children. Journalists and photojournalists were present, and the news was reported throughout the island the following day. In addition, a photo appeared in the newspaper El Imparcial, which was circulated to members of the U.S. Congress.[6]

The Insular Police, a force resembling the National Guard, had been trained by U.S. military personnel. They were under the command of General Blanton Winship, the U.S.-appointed governor of Puerto Rico, who gave the order to attack the Ponce march on Palm Sunday.[7]

Salón Boricua

Santiago Díaz worked as a barber at 351 Calle Colton (Colton Street), Esquina Barbosa (at the corner of Barbosa Street) of Barrio Obrero, in a shop called Salón Boricua.[3] The word Boricua is synonymous with "Puerto Rican," and is a self-referential term which Puerto Ricans commonly employ. The word is derived from the words Borinquen and Boriken, the name which the native Taínos gave to the island before the arrival of the Spanish Conquistadors.[8]

When he purchased the business in 1932 from José Maldonado Román, who was ailing from throat cancer, Santiago Díaz became the sole owner of the business.[9][10]

Salón Boricua was often frequented by Jose Grajales and Ramon Medina Ramirez, both leaders of the Nationalist Party of San Juan, and often served as a Nationalist meeting place. Santiago Díaz also befriended party leader and president Pedro Albizu Campos, who himself became a regular customer.[11] Over time, Santiago Díaz became Albizu Campos' personal barber and one of his most trusted advisors.[12][13][14]

Events leading to the revolt

On May 21, 1948, a bill was introduced before the Puerto Rican Senate which would restrain the rights of the Independence and Nationalist movements in the island. The Senate, which was controlled by the PPD and presided by Luis Muñoz Marín, rapidly approved the bill,[15] and it was signed and made into law on June 10, 1948, by the U.S.-appointed governor of Puerto Rico, Jesús T. Piñero. Law 53, which resembled the anti-communist Smith Law passed in the United States,[16] became known as the Ley de la Mordaza (Gag Law).

The law made it illegal to display a Puerto Rican flag, to sing a patriotic tune, to talk of independence, or fight for liberation of the island. It also made it a crime to print, publish, exhibit or sell Puerto Rican patriotic literature; or to organize or help anyone organize any society, group or assembly of people who intended to challenge the U.S. insular government. Anyone accused and found guilty of disobeying Law 53 could be imprisoned for ten years, fined $10,000 dollars (US), or both. According to Dr. Leopoldo Figueroa, a member of the Puerto Rico House of Representatives, the law was repressive and was in violation of the First Amendment of the US Constitution which guarantees Freedom of Speech. He pointed out that the law as such was a violation of the civil rights of the people of Puerto Rico.[17]

On June 21, 1948, Albizu Campos gave a speech in the town of Manati where Nationalists from all over the island had gathered, in case the police attempted to arrest him. Later that month Campos visited Blanca Canales and her cousins Elio and Griselio Torresola, the nationalist leaders of the town of Jayuya. Griselio soon moved to New York where he met and befriended Oscar Collazo.[3]

Uprisings

From 1949 to 1950, the Nationalists in the island began to plan and prepare an armed revolution, hoping that the United Nations would take notice and intervene on their behalf. The revolution was to occur in 1952, on the date the United States Congress was to approve the creation of the political status Free Associated State ("Estado Libre Associado") for Puerto Rico. The reason behind Albizu Campos' call for an armed revolution was that he considered the "new" status a colonial farce.

The police disrupted this timetable and the Nationalist revolution was accelerated by two years. On October 26, 1950, Albizu Campos was holding a meeting in Fajardo when he received word that his house in San Juan was surrounded by police waiting to arrest him. He was also told that the police had already arrested other Nationalist leaders. He escaped from Fajardo and ordered the revolution to start.

The next day, on October 27, the police fired upon a caravan of Nationalists in the town of Peñuelas, and killed four of them. This police massacre inflamed the entire population of Puerto Rico, and the outcry was immediate.[18]

The first armed battle of the Nationalist uprisings occurred in the early morning of October 29, in the barrio Macaná of town of Peñuelas. The Insular Police surrounded the house of the mother of Melitón Muñiz Santos, the president of the Peñuelas Nationalist Party in the barrio Macaná, under the pretext that he was storing weapons for the Nationalist Revolt. Without warning, the police fired upon the Nationalists in the house and a firefight between both factions ensued, resulting on the death of two Nationalists and wounding of six police officers.[19] Nationalists Meliton Muñoz Santos, Roberto Jaume Rodriguez, Estanislao Lugo Santiago, Marcelino Turell, William Gutirrez and Marcelino Berrios were arrested and accused of participating in an ambush against the local Insular Police.[20][21]

The very next day, October 30, saw Nationalist uprisings throughout Puerto Rico, including seven towns: Ponce, Mayagüez, Naranjito, Arecibo, Utuado (Utuado Uprising), Jayuya (Jayuya Uprising) and San Juan (San Juan Nationalist revolt).

Despite all this turmoil, and an island-wide revolt, all accurate news were prevented from spreading outside of Puerto Rico. Instead, the entire revolt was called "an incident between Puerto Ricans."[22]

Gunfight at the Salón Boricua

Upon learning that the police wanted to arrest Albizu Campos, Santiago Díaz, who then was the president of the Santurce Municipal Board of officers of the PRNP,[23] sent a telegram to the Attorney General of Puerto Rico in the early hours of October 31, 1950, offering his services as an intermediary. He then opened his barbershop, to await an answer which never arrived. Instead, unbeknownst to Santiago Díaz, 15 police officers and 25 National Guardsmen were sent that very afternoon, to lay siege to his barbershop .[1]

As they surrounded the barbershop, these 40 armed men believed that a large group of Nationalists were inside, and sent an police officer to investigate. Santiago Díaz believed that he was going to be shot by this officer, and armed himself with a pistol. The situation escalated quickly, Santiago Díaz shot first, and the police all fired back - with machine guns, rifles, carbines, revolvers, and even grenades.[1]

|

|

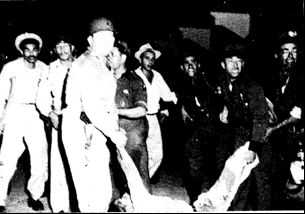

The firefight lasted three hours. It finally ended when Santiago Díaz received five bullet wounds, one of them to the head. A staircase also collapsed on him. Outside in the street, two bystanders and a child were wounded. This gun battle between 40 heavily armed policemen and one courageous barber, made Puerto Rican radio history. It was the first time an event of this magnitude was transmitted "live" via the radio airwaves, and the entire island was left in shock.[1] The reporters who covered the event for Radio WKAQ and WIAC were Luis Enrique "Bibí" Marrero, Víctor Arrillaga, Luis Romanacce and 18 year-old Miguel Angel Alvarez.[24][25]

Thinking he was dead, the attacking policemen dragged Santiago Díaz out of his barbershop.[1] When they realized he was still alive, Santiago Díaz was sent to San Juan Municipal Hospital. He was hospitalized with fellow Nationalists Gregorio Hernández (who attacked La Fortaleza, the governor's mansion) and Jesús Pomales González (one of five Nationalists assigned to attack the Federal Court House).[26]

Aftermath

After the police assault at the Salón Boricua, Santiago Díaz recovered from most of his wounds, but not from the gunshot to his head. Upon release from the hospital he was arrested and taken before a federal judge, where he faced charges for "intent to commit murder" and other events related to the Nationalist Uprisings of October 1950. Although he did not participate in the uprisings, he was convicted and sentenced to serve 17 years and 6 months in prison at the Insular Penitentiary in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico.

On October 14, 1952, Santiago Díaz was granted a pardon in all the cases concluded or pending against him by Puerto Rican Governor Luis Muñoz Marín. The governor specified that Santiago Diaz's activities on behalf of Puerto Rico independence were not to be curtailed, unless they advocated the use of anti-democratic methods, force, or violence. The pardon was conditional, under the supervision and control of the Insular Parole Board. Upon receiving this pardon, Santiago Díaz was immediately freed.[11]

Later years

Santiago Díaz never fully recovered from his head wound and moved with his wife to Santa Juanita, Bayamon. He ceased his political activities in the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and became a member, and eventually a deacon, of the Disciples of Christ Church. Santiago Díaz died on March 1982 at his home in Bayamon.[11]

Notes

- ↑ This name uses Spanish naming customs; the first or paternal family name is Santiago and the second or maternal family name is Díaz.

See also

- Puerto Rican Nationalist Party Revolts of the 1950s

- Puerto Rican Nationalist Party

- Ponce Massacre

- Río Piedras massacre

- Puerto Rican Independence Party

- List of famous Puerto Ricans

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 The Nationalist Insurrection of 1950

- ↑ 19 Were killed including 1 policemen caught in the cross-fire, The Washington Post Tuesday, December 28, 1999; Page A03. "Apology Isn't Enough for Puerto Rico Spy Victims."

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Latino Americans and political participation. ABC-CLIO. 2004. ISBN 1-85109-523-3. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ "Latino Americans and Political Participation: A Reference Handbook". By Sharon Ann Navarro and Armando Xavier Mejia. 2004. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc. ISBN=1-85109-123-3.

- ↑ Ponce Massacre, Com. of Inquiry, 1937. Ponce Massacre, Commission of Inquiry, 1937. LLMC Central. The Law Library Microform Consortium. Kaneohe, HI. 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ 19 Were killed including 2 policemen caught in the cross-fire, The Washington Post Tuesday, December 28, 1999; Page A03. "Apology Isn't Enough for Puerto Rico Spy Victims."

- ↑ Insular Police.

- ↑ Uiban Dictionary

- ↑ Starr, Douglas.Science 25 April 2003: Vol. 300. no. 5619, pp. 573 - 574

- ↑ Puerto Ricans Outraged Over Secret Medical Experiments

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 FBI-Puerto Rico Secret Files; Page 24

- ↑ Stephen Hunter & John Bainbridge, Jr., American Gunfight, p. 271; Simon & Schuster pub., 2005; ISBN 978-0-7432-6068-8

- ↑ Federico Ribes Tovar, Albizu Campos: Puerto Rican Revolutionary, pp.107-110; Plus Ultra Educational pub., 1971

- ↑ Marisa Rosado, Pedro Albizu Campos: Las Llamas de la Aurora, pp.357-358; Ediciones Puerto pub., 2008; ISBN 1-933352-62-0

- ↑ "La obra jurídica del Profesor David M. Helfeld (1948-2008)'; by: Dr. Carmelo Delgado Cintrón

- ↑ "Puerto Rican History". Topuertorico.org. January 13, 1941. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ↑ La Gobernación de Jesús T. Piñero y la Guerra Fría

- ↑ Puerto Rico history

- ↑ El ataque Nacionalista a La Fortaleza. by Pedro Aponte Vázquez. Page 7. Publicaciones RENÉ. ISBN 978-1-931702-01-0

- ↑ Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico-FBI files

- ↑ El ataque Nacionalista a La Fortaleza; by Pedro Aponte Vázquez; Page 7; Publisher: Publicaciones RENÉ; ISBN 978-1-931702-01-0

- ↑ NY Latino

- ↑ "FBI Files"; "Puerto Rico Nationalist Party"; SJ 100-3; Vol. 23; pages 104-134.

- ↑ Premio a Jesús Vera Irizarry

- ↑ WAPA

- ↑ "El ataque Nacionalista a La Fortaleza"; by Pedro Aponte Vázquez; Page 7; Publisher: Publicaciones RENÉ; ISBN 978-1-931702-01-0