Vichy France

| French State l'État français | ||||||

| Client state of Nazi Germany (1940–42) Puppet state of Nazi Germany (1942–44) | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| Motto "Travail, Famille, Patrie" "Work, Family, Fatherland" | ||||||

| Anthem La Marseillaise The Song of Marseille (official) Maréchal, nous voilà! [2] Marshal, here we are! (unofficial) | ||||||

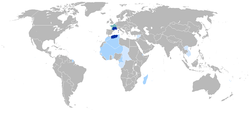

Dark blue: De jure part of French State. Teal: De jure part of French State occupied by the Axis. Sky blue: Vichy possessions under Vichy control. Lightest blue: Vichy possessions lost relatively early. Red: French possessions never held by Vichy. | ||||||

| Capital | Vichy (de facto) Parisa (de jure) | |||||

| Capital-in-exile | Sigmaringen (1944–1945) | |||||

| Languages | French | |||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | |||||

| Government | Authoritarian stateb | |||||

| Chief of the French State | ||||||

| - | 1940–1944 | Philippe Pétain | ||||

| President of the Council of Ministers | ||||||

| - | 1940–1942 | Philippe Pétain | ||||

| - | 1942–1944 | Pierre Laval | ||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||

| Historical era | World War II | |||||

| - | End of the Battle of France | 22 June 1940 | ||||

| - | Pétain given full powers | 10 July 1940 | ||||

| - | Southern France occupied | 11 November 1942 | ||||

| - | Liberation of Paris | 25 August 1944 | ||||

| - | Liberation of France | June – November 1944 | ||||

| - | Capture of Sigmaringen | 22 April 1945 | ||||

| Currency | Franc | |||||

| a. | Paris remained the formal capital of the French State, though the Vichy regime never operated from it. | |||||

| b. | Although the French Republic's institutions were officially maintained, the word "Republic" never occurred in any official document of the Vichy government. | |||||

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of France | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governments of France |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vichy France, officially the French State (l'État français), was France during the regime of Marshal Philippe Pétain, during World War II, from the German victory in the Battle of France (July 1940) to the Allied liberation in August 1944.[3] Following the defeat in June 1940, President Albert Lebrun appointed Marshal Pétain as premier. After making peace with Germany, Pétain and his government voted to reorganize the discredited Third Republic into an authoritarian regime.

The newly formed French State maintained nominal sovereignty over the whole of French territory as defined by the Second Armistice at Compiègne. However, Vichy maintained full sovereignty only in the unoccupied southern Zone libre ("free zone"), while retaining limited authority in the Wehrmacht-occupied northern zone, the Zone occupée ("occupied zone"). The occupation was to be a provisional state of affairs pending the conclusion of the war in the west, which at the time appeared imminent. In November 1942, however, the Zone libre was also occupied, with Germany closely supervising all French officials.

Marshal Pétain collaborated with the German occupying forces in exchange for an agreement not to divide France between the Axis powers. Germany kept two million French soldiers in Germany as forced laborers to enforce its terms. Vichy authorities aided in the rounding-up of Jews and other "undesirables". At times in the colonies Vichy French military forces actively opposed the Allies. Much of the French public initially supported the new government despite its pro-Nazi policies, often seeing it as necessary to maintain a degree of French autonomy and territorial integrity.[4]

The legitimacy of Vichy France and Pétain's leadership was constantly challenged by the exiled General Charles de Gaulle, based in London, who claimed to represent the legitimacy and continuity of the French nation. The overseas French colonies were originally under Vichy control, but it lost one after another to de Gaulle's Free French movement. Public opinion turned against the Vichy regime and the occupying German forces over time and resistance to them increased. Following the Allied invasion of France in June 1944, de Gaulle proclaimed the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF).

Following France's liberation in summer 1944, most of the Vichy regime's leaders fled or were put on trial by the GPRF and a number were executed for treason. Thousands of collaborators were killed without trial by local Resistance forces. Pétain was sentenced to death for treason, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Only four senior Vichy officials were tried for crimes against humanity, although many more had participated in the deportation of Jews for extermination in concentration camps, abuses of prisoners and severe acts against members of the Resistance.

Overview

Vichy France was established after France surrendered to Germany on 22 June 1940, and took its name from the government's administrative centre of Vichy, in central France. Paris remained the official capital, to which Pétain always intended to return the government when this became possible.

In 1940, Marshal Pétain was known mainly as a World War One hero, the victor of Verdun. As last Prime Minister of the Third Republic, Pétain, a reactionary by inclination, blamed the Third Republic's democracy for France's quick defeat. He set up a paternalistic, semi-fascist regime that actively collaborated with Germany, its official neutrality notwithstanding. The Vichy government cooperated with the Nazis' racial policies.

It is a common misconception that the Vichy Regime administered only the unoccupied zone of southern France (named "free zone" [zone libre] by Vichy), while the Germans directly administered the occupied zone.[citation needed] In theory, the civil jurisdiction of the Vichy government extended over most of metropolitan France; only the disputed border territory of Alsace-Lorraine was placed under direct German administration.[5] Similarly, a sliver of French territory in the Alps was under direct Italian administration from June 1940 to September 1943. Throughout the rest of the country, civil servants were under the authority of French ministers in Vichy.[citation needed] René Bousquet, the head of French police nominated by Vichy, exercised his power directly in Paris through his second-in-command, Jean Leguay, who coordinated raids with the Nazis. German laws, however, took precedence over French ones in the occupied territories, and the Germans often rode roughshod over the sensibilities of Vichy administrators.

On 11 November 1942, the Germans launched Operation Case Anton, occupying southern France, following the landing of the Allies in North Africa (Operation Torch). Although Vichy's "Armistice Army" was disbanded, thus diminishing Vichy's independence, the abolition of the line of demarcation in March 1943 made civil administration easier. Vichy continued to exercise jurisdiction over almost all of France until the collapse of the regime following the Allied invasion in June 1944.

Until 23 October 1944,[6] the Vichy Regime was acknowledged as the official government of France by the United States and other countries, including Canada, which were at the same time at war with Germany. The United Kingdom maintained unofficial contacts with Vichy, at least until it became apparent that the Vichy Prime Minister, Pierre Laval, intended full collaboration with the Germans. Even after that it maintained an ambivalent attitude towards the alternative Free French movement and future government.

The Vichy government's claim that it was the de jure French government was challenged by the Free French Forces of Charles de Gaulle (based first in London and later in Algiers) and subsequent French governments. They continuously held that the Vichy Regime was an illegal government run by traitors. Historians have particularly debated the circumstances of the vote granting full powers to Pétain on 10 July 1940. The main arguments advanced against Vichy's right to incarnate the continuity of the French State were based on the pressure exerted by Laval on deputies in Vichy, and on the absence of 27 deputies and senators who had fled on the ship Massilia, and could thus not take part in the vote.

Ideology

Vichy sought an anti-modern counter-revolution. The Right in France, with strength in the aristocracy and among Catholics, had never accepted the republican traditions of the French Revolution. It demanded a return to traditional lines culture and religion and embraced authoritarianism while dismissing democracy.[7] The Communist element, strongest in labour unions, turned against the regime in June 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Vichy was intensely anti-Communist and generally pro-Nazi; Payne finds that it, "was distinctly rightist and authoritarian but never fascist."[8] Paxton analyzes the entire range of Vichy supporters, from reactionaries to moderate liberal modernizers, and concludes that genuine fascist elements had but minor roles in most sectors.[9]

The regime tried to assert its legitimacy by symbolically connecting itself to the Gallo-Roman period of France's history, and celebrated the Gaul chieftain Vercingetorix as the "founder" of the nation.[10] it was maintained that as the defeat of the Gauls in the Battle of Alesia had been the moment in French history when a sense of common nationhood was born, the defeat of 1940 would again unify the nation.[10] The regime's "Francisque" insignia featured two symbols from the Gallic period: the baton and the double-headed hatchet (labrys) arranged so as to resemble the fasces, symbol of the Italian Fascists.[10]

Fall of France and establishment of the Vichy Regime

France declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939 following the German invasion of Poland, which took place two days prior. After the eight-month Phoney War, the Germans launched their offensive in the west on 10 May 1940. Within days, it became clear that French forces were overwhelmed and that military collapse was imminent.[11] Government and military leaders, deeply shocked by the débâcle, debated how to proceed. Many officials, including Prime Minister Paul Reynaud, wanted to move the government to French territories in North Africa, and continue the war with the French Navy and colonial resources. Others, particularly the Vice-Premier Philippe Pétain and the Commander-in-Chief, General Maxime Weygand, insisted that the responsibility of the government was to remain in France and share the misfortune of its people. The latter view called for an immediate cessation of hostilities.[ 1]:121–126

While this debate continued, the government was forced to relocate several times, finally reaching Bordeaux, to avoid capture by advancing German forces. Communications were poor and thousands of civilian refugees clogged the roads. In these chaotic conditions, advocates of an armistice gained the upper hand. The Cabinet agreed on a proposal to seek armistice terms from Germany, with the understanding that, should Germany set forth dishonourable or excessively harsh terms, France would retain the option to continue to fight. General Charles Huntziger, who headed the French armistice delegation, was told to break off negotiations if the Germans demanded the occupation of all metropolitan France, the French fleet or any of the French overseas territories. They did not.[12]

Prime Minister Paul Reynaud was in favor of continuing the war, from North Africa if necessary; however, he was soon outvoted by those who advocated surrender. Facing an untenable situation, Reynaud resigned and, on his recommendation, President Albert Lebrun appointed the 84-year-old Pétain as his replacement on 16 June. The Armistice with France (Second Compiègne) agreement was signed on 22 June. A separate agreement was reached with Italy, which had entered the war against France on 10 June, well after the outcome of the battle was decided.

Adolf Hitler had a number of reasons for agreeing to an armistice. He wanted to ensure that France did not continue to fight from North Africa, and he wanted to ensure that the French Navy was taken out of the war. In addition, leaving a French government in place would relieve Germany of the considerable burden of administering French territory, particularly as he turned his attentions toward Britain. Finally, as Germany lacked a navy sufficient to occupy France's overseas territories, Hitler's only practical recourse to deny the British use of them was to maintain France's status as a supposedly independent and neutral nation.

Conditions of armistice and 10 July 1940 vote of full powers

The armistice divided France into occupied and unoccupied zones: northern and western France including the entire Atlantic coast were occupied by Germany, and the remaining two-fifths of the country were under the control of the French government with the capital at Vichy under Pétain. Ostensibly, the French government administered the entire territory.

Prisoners

Germany took two million French soldiers as prisoners of war and sent them to camps in Germany. About one third were released on various terms by 1944. Of the remainder, the officers and NCOs (corporals and sergeants) were kept in camps and did not work. The privates were sent first to "Stalag" camps for processing and then were put out to work. About half of them worked in German agriculture, where food supplies were adequate and controls were lenient. The others worked in factories or mines, where conditions were much harsher.[13]

Army of the Armistice

The Germans preferred to occupy northern France themselves. The French had to pay costs for the 300,000-strong German occupation army, amounting to 20 million Reichmarks per day, paid at the artificial rate of twenty francs to the Mark. This was 50 times the actual costs of the occupation garrison. The French government also had responsibility for preventing citizens from escaping into exile.

Article IV of the Armistice allowed for a small French army—the Army of the Armistice (Armée de l'Armistice)—stationed in the unoccupied zone, and for the military provision of the French colonial empire overseas. The function of these forces was to keep internal order and to defend French territories from Allied assault. The French forces were to remain under the overall direction of the German armed forces.

The exact strength of the Vichy French Metropolitan Army was set at 3,768 officers, 15,072 non-commissioned officers, and 75,360 men. All members had to be volunteers. In addition to the army, the size of the Gendarmerie was fixed at 60,000 men plus an anti-aircraft force of 10,000 men. Despite the influx of trained soldiers from the colonial forces (reduced in size in accordance with the Armistice), there was a shortage of volunteers. As a result, 30,000 men of the "class of 1939" were retained to fill the quota. At the beginning of 1942 these conscripts were released, but there was still an insufficient number of men. This shortage would remain until the dissolution, despite Vichy appeals to the Germans for a regular form of conscription.

The Vichy French Metropolitan Army was deprived of tanks and other armored vehicles, and was desperately short of motorized transport, a particular problem for cavalry units. Surviving recruiting posters stress the opportunities for athletic activities, including horsemanship – which reflects both the general emphasis placed by the Vichy regime on rural virtues and outdoor activities, and the realities of service in a small and technologically backward military force. Traditional features characteristic of the pre-1940 French Army, such as kepis and heavy capotes (buttoned-back greatcoats), were replaced by berets and simplified uniforms.

The Vichy authorities did not deploy the Army of the Armistice against resistance groups active in the south of France, reserving this role to the Vichy Milice (militia).[14] Members of the regular army were therefore able to defect in significant numbers to the Maquis, following the German occupation of southern France and the disbandment of the Army of the Armistice in November 1942. By contrast, the Milice continued to collaborate and its members became subject to reprisals after the Liberation.

Vichy French colonial forces were reduced in accordance with the terms of the Armistice; still, in the Mediterranean area alone, the Vichy French had nearly 150,000 men in arms. There were approximately 55,000 in French Morocco, 50,000 in Algeria, and almost 40,000 in the "Army of the Levant" (Armée du Levant), in Lebanon and Syria. Colonial forces were allowed to keep some armored vehicles, though these were mostly "vintage" tanks as old as the World War I-era Renault FT.

German custody

France was required to turn over any German citizens within the country whom the Germans demanded custody of. The French thought this to be a "dishonourable" term, since it would require France to hand over persons who had entered France seeking refuge from Germany. Attempts to negotiate the point with Germany were unsuccessful, and the French decided not to press the issue to the point of refusing the Armistice, though they may have hoped to ameliorate the requirement in future negotiations with Germany after the signing.

Vichy government

On 1 July 1940, the Parliament and the government gathered in the quiet spa town of Vichy, their provisional capital in central France. (Lyon, France's second-largest city, would have been a more logical choice but mayor Édouard Herriot was too associated with the Third Republic. Marseilles had a reputation as the dangerous "Chicago" of France. Toulouse was too remote and had a left-wing reputation. Vichy was centrally located and had many hotels for ministers to stay at.)[ 1]:142 Laval and Raphaël Alibert began their campaign to convince the assembled Senators and Deputies to vote full powers to Pétain. They used every means available, promising ministerial posts to some while threatening and intimidating others. They were aided by the absence of popular, charismatic figures who might have opposed them, such as Georges Mandel and Édouard Daladier, then aboard the ship Massilia on their way to North Africa and exile. On 10 July the National Assembly, comprising both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, voted by 569 votes to 80, with 20 voluntary abstentions, to grant full and extraordinary powers to Marshal Pétain. By the same vote, they also granted him the power to write a new constitution.[15]

Most legislators believed that democracy would continue, albeit with a new constitution. Although Laval said on 6 July that "parliamentary democracy has lost the war; it must disappear, ceding its place to an authoritarian, hierarchical, national and social regime", the majority trusted in Pétain. Léon Blum, who voted no, wrote three months later that Laval's "obvious objective was to cut all the roots that bound France to its republican and revolutionary past. His 'national revolution' was to be a counterrevolution eliminating all the progress and human rights won in the last one hundred and fifty years".[16] The minority of mostly Radicals and Socialists who opposed Laval became known as the Vichy 80. Deputies and senators who voted to grant full powers to Pétain were condemned on an individual basis after the liberation.

The majority of French historians and all post-war French governments contend this vote was illegal. Three main arguments are put forward:

- Abrogation of legal procedure

- The impossibility for parliament to delegate its constitutional powers without controlling its use a posteriori

- The 1884 constitutional amendment making it impossible to put into question the "republican form" of the regime

Julian T. Jackson wrote, however, that "There seems little doubt, therefore, that at the beginning Vichy was both legal and legitimate." He stated that if legitimacy comes from popular support, Pétain's massive popularity in France until 1942 made his government legitimate; if legitimacy comes from diplomatic recognition, over 40 countries including the United States, Canada, and China recognized the Vichy government. According to Jackson, de Gaulle's Free French acknowledged the weakness of its case against Vichy's illegality by citing multiple dates (16 June 23 June, and 10 July) for the start of its illegitimate rule.[17]:134 Nations recognized the Vichy government despite de Gaulle's attempts in London to dissuade them; only the German occupation of all of France in November 1942 ended diplomatic recognition. Partisans of the Vichy point out that the revision was voted by the two chambers (the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies), in conformity with the law.

The argument concerning the abrogation of procedure is based on the absence and non-voluntary abstention of 176 representatives of the people – the 27 on board the Massilia, and an additional 92 deputies and 57 senators, some of whom were in Vichy, but not present for the vote. In total, the parliament was composed of 846 members, 544 Deputies and 302 Senators. One Senator and 26 Deputies were on the Massilia. One Senator did not vote. 8 Senators and 12 Deputies voluntarily abstained. 57 Senators and 92 Deputies involuntarily abstained. Thus, out of a total of 544 Deputies, only 414 voted; and out of a total of 302 Senators, only 235 voted. Of these, 357 Deputies voted in favor of Pétain and 57 against, while 212 Senators voted for Pétain, and 23 against. Although Pétain could claim for himself legality – particularly in comparison with the essentially self-appointed leadership of Charles de Gaulle – the dubious circumstances of the vote explain why a majority of French historians do not consider Vichy a complete continuity of the French state.[18]

The text voted by the Congress stated:

The National Assembly gives full powers to the government of the Republic, under the authority and the signature of Marshall Pétain, to the effect of promulgating by one or several acts a new constitution of the French state. This constitution must guarantee the rights of labor, of family and of the fatherland. It will be ratified by the nation and applied by the assemblies which it has created.[19]

The Constitutional Acts of 11 and 12 July 1940[20] granted to Pétain all powers (legislative, judicial, administrative, executive – and diplomatic) and the title of "head of the French state" (chef de l'État français), as well as the right to nominate his successor. On 12 July Pétain designated Laval as Vice-President and his designated successor, and appointed Fernand de Brinon as representative to the German High Command in Paris. Pétain remained the head of the Vichy regime until 20 August 1944. The French national motto, Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité (Freedom, Equality, Brotherhood), was replaced by Travail, Famille, Patrie (Work, Family, Fatherland); it was noted at the time that TFP also stood for the criminal punishment of "travaux forcés à perpetuité" ("forced labor in perpetuity").[21] Reynaud was arrested in September 1940 by the Vichy government and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1941 before the opening of the Riom Trial.

Pétain was reactionary by nature, his status as a hero of the Third Republic notwithstanding. Almost as soon as he was granted full powers, Pétain began blaming the Third Republic's democracy and endemic corruption for France's humiliating defeat. Accordingly, his regime soon began taking on authoritarian—and in some cases, overtly fascist—characteristics. Democratic liberties and guarantees were immediately suspended.[ 1] The crime of "felony of opinion" (délit d'opinion) was re-established, effectively repealing freedom of thought and of expression; critics were frequently arrested. Elective bodies were replaced by nominated ones. The "municipalities" and the departmental commissions were thus placed under the authority of the administration and of the prefects (nominated by and dependent on the executive power). In January 1941 the National Council (Conseil National), composed of notables from the countryside and the provinces, was instituted under the same conditions. Despite the clear authoritarian cast of Pétain's regime, he did not formally institute a one-party state, maintained the Tricolor and other symbols of republican France, and unlike many far rightists was not an anti-Dreyfusard.

State collaboration with Germany

Historians distinguish between a state collaboration followed by the regime of Vichy, and "collaborationists", which usually refer to the French citizens eager to collaborate with Germany and who pushed towards a radicalization of the regime. "Pétainistes", on the other hand, refers to French people who supported Marshal Pétain, without being too keen on collaboration with Germany (although accepting Pétain's state collaboration). State collaboration was illustrated by the Montoire (Loir-et-Cher) interview in Hitler's train on 24 October 1940, during which Pétain and Hitler shook hands and agreed on this cooperation between the two states. Organized by Laval, a strong proponent of collaboration, the interview and the handshake were photographed, and Nazi propaganda made strong use of this photo to gain support from the civilian population. On 30 October 1940, Pétain officialized state collaboration, declaring on the radio: "I enter today on the path of collaboration...."[22] On 22 June 1942 Laval declared that he was "hoping for the victory of Germany." The sincere desire to collaborate did not stop the Vichy government from organising the arrest and even sometimes the execution of German spies entering the Vichy zone, as Simon Kitson's recent research has demonstrated.[23]

The composition of the Vichy cabinet, and its policies, were mixed. Many Vichy officials such as Pétain, though not all, were reactionaries who felt that France's unfortunate fate was a result of its republican character and the actions of its left-wing governments of the 1930s, in particular of the Popular Front (1936–1938) led by Léon Blum. Charles Maurras, a monarchist writer and founder of the Action Française movement, judged that Pétain's accession to power was, in that respect, a "divine surprise", and many people of the same political persuasion believed it preferable to have an authoritarian government similar to that of Francisco Franco's Spain, even if under Germany's yoke, than to have a republican government. Others, like Joseph Darnand, were strong anti-Semites and overt Nazi sympathizers. A number of these joined the Légion des Volontaires Français contre le Bolchévisme (Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism) units fighting on the Eastern Front, which later became the SS Charlemagne Division.[24]

On the other hand, technocrats such as Jean Bichelonne or engineers from the Groupe X-Crise used their position to push various state, administrative and economic reforms. These reforms would be one of the strongest elements arguing in favor of the thesis of a continuity of the French administration before and after the war. Many of these civil servants and the reforms they advocated were retained after the war. Just as the necessities of a war economy during the First World War had pushed forward state measures which reorganized the economy of France against the prevailing classical liberal theories – structures retained after the 1919 Treaty of Versailles – reforms adopted during World War II were kept and extended. Along with 15 March 1944 Charter of the Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR), which gathered all Resistance movements under one unified political body, these reforms were a primary instrument in the establishment of post-war dirigisme, a kind of semi-planned economy which led to France becoming the modern social democracy it is now. Examples of such continuities include the creation of the "French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems" by Alexis Carrel, a renowned physician who also supported eugenics. This institution would be renamed National Institute of Demographic Studies (INED) after the war, and exists to this day. Another example is the creation of the national statistics institute, renamed INSEE after the Liberation. The reorganization and unification of the French police by René Bousquet, who created the groupes mobiles de réserve (GMR, Reserve Mobile Groups), is another example of Vichy policy reform and restructuring maintained by subsequent governments. A national paramilitary police force, the GMR was occasionally used in actions against the French Resistance, but its main purpose was to enforce Vichy authority through intimidation and repression of the civilian population. After Liberation, some of its units would be merged with the Free French Army to form the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité (CRS, Republican Security Companies), France's main anti-riot force.

Vichy's racial policies and collaboration

Germany interfered little in internal French affairs for the first two years after the armistice, as long as public order was maintained.[ 1]:139 As soon as it was established, Pétain's government voluntarily took measures against the undesirables: Jews, métèques (immigrants from Mediterranean countries), Freemasons, Communists, Gypsies, homosexuals,[citation needed] and left-wing activists. Inspired by Charles Maurras' conception of the "Anti-France" (which he defined as the "four confederate states of Protestants, Jews, Freemasons and foreigners"), Vichy persecuted these supposed enemies.

In July 1940, Vichy set up a special Commission charged with reviewing naturalizations granted since the 1927 reform of the nationality law. Between June 1940 and August 1944, 15,000 persons, mostly Jews, were denaturalized.[25] This bureaucratic decision was instrumental in their subsequent internment.

The internment camps already opened by the Third Republic were immediately put to new use, ultimately becoming transit camps for the implementation of the Holocaust and the extermination of all "undesirables", including the Romani people (who refer to the extermination of Gypsies as Porrajmos). A law of 4 October 1940 authorized internments of foreign Jews on the sole basis of a prefectoral order,[26] and the first raids took place in May 1941. Vichy imposed no restrictions on black people in the Unoccupied Zone; the regime even had a mulatto cabinet minister, the Martinique-born lawyer Henry Lemery.[27]

The Third Republic had first opened concentration camps during World War I for the internment of enemy aliens, and later used them for other purposes. Camp Gurs, for example, had been set up in southwestern France after the fall of Spanish Catalonia, in the first months of 1939, during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), to receive the Republican refugees, including Brigadists from all nations, fleeing the Francists. After Édouard Daladier's government (April 1938 – March 1940) took the decision to outlaw the French Communist Party (PCF) following the German-Soviet non-aggression pact (aka Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) signed in August 1939, these camps were also used to intern French communists. Drancy internment camp was founded in 1939 for this use; it later became the central transit camp through which all deportees passed on their way to concentration and extermination camps in the Third Reich and in Eastern Europe. When the Phoney War started with France's declaration of war against Germany on 3 September 1939, these camps were used to intern enemy aliens. These included German Jews and anti-fascists, but any German citizen (or Italian, Austrian, Polish, etc.) could also be interned in Camp Gurs and others. As the Wehrmacht advanced into Northern France, common prisoners evacuated from prisons were also interned in these camps. Camp Gurs received its first contingent of political prisoners in June 1940. It included left-wing activists (communists, anarchists, trade-unionists, anti-militarists, etc.) and pacifists, but also French fascists who supported the victory of Italy and Germany. Finally, after Pétain's proclamation of the "French state" and the beginning of the implementation of the "Révolution nationale" ("National Revolution"), the French administration opened up many concentration camps, to the point that, as historian Maurice Rajsfus wrote: "The quick opening of new camps created employment, and the Gendarmerie never ceased to hire during this period."[28]

Besides the political prisoners already detained there, Gurs was then used to intern foreign Jews, stateless persons, Gypsies, homosexuals, and prostitutes. Vichy opened its first internment camp in the northern zone on 5 October 1940, in Aincourt, in the Seine-et-Oise department, which it quickly filled with PCF members.[29] The Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans, in the Doubs, was used to intern Gypsies.[30] The Camp des Milles, near Aix-en-Provence, was the largest internment camp in the Southeast of France; 2,500 Jews were deported from there following the August 1942 raids.[31] Exiled Republican, antifascist Spaniards who had sought refuge in France after the recent victory in Spain of Franco's nationalist side, were then deported, and 5,000 of them died in Mauthausen concentration camp.[32] In contrast, the French colonial soldiers were interned by the Germans on French territory instead of being deported.[32]

Besides the concentration camps opened by Vichy, the Germans also opened some Ilags (Internierungslager), for the detainment enemy aliens, on French territory; in Alsace, which was under the direct administration of the Reich, they opened the Natzweiler camp, which was the only concentration camp created by the Nazis on French territory. Natzweiler included a gas chamber which was used to exterminate at least 86 detainees (mostly Jewish) with the aim obtaining a collection of undamaged skeletons (as this mode of execution did no damage to the skeletons themselves) for the use of Nazi professor August Hirt.

The Vichy government enacted a number of racial laws. In August 1940, laws against antisemitism in the media (the Marchandeau Act) were repealed, while the decree n°1775 September 5, 1943, denaturalized a number of French citizen], in particular Jews from Eastern Europe.[32] Foreigners were rounded-up in "Foreign Workers Groups" (groupements de travailleurs étrangers) and, as with the colonial troops, used by the Germans as manpower.[32] The Statute on Jews excluded them from the civil administration.

Vichy also enacted racial laws in its French territories in North Africa (Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia). "The history of the Holocaust in France's three North African colonies (Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia) is intrinsically tied to France's fate during this period."[33][34][35][36][37][38]

With regard to economic contribution to the German economy it is estimated that France provided 42% of the total foreign aid.[39]

Eugenics policies

In 1941, Nobel Prize winner Alexis Carrel, an early proponent of eugenics and euthanasia, and a member of Jacques Doriot's French Popular Party (PPF),[citation needed] advocated for the creation of the Fondation Française pour l'Étude des Problèmes Humains (French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems), using connections to the Pétain cabinet. Charged with the "study, in all of its aspects, of measures aimed at safeguarding, improving and developing the French population in all of its activities", the Foundation was created by decree of the collaborationist Vichy regime in 1941, and Carrel appointed as 'regent'.[40] The Foundation also had for some time as general secretary François Perroux.[citation needed]

The Foundation was behind 16 December 1942 Act mandating the "prenuptial certificate", which required all couples seeking marriage to submit to a biological examination, to insure the "good health" of the spouses, in particular with regard to sexually transmitted diseases (STD) and "life hygiene".[citation needed] Carrel's institute also conceived the "scholar booklet" ("livret scolaire"), which could be used to record students' grades in French secondary schools, and thus classify and select them according to scholastic performance.[citation needed] Besides these eugenic activities aimed at classifying the population and improving its health, the Foundation also supported 11 October 1946 law instituting occupational medicine, enacted by the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF) after the Liberation.[citation needed]

The Foundation initiated studies on demographics (Robert Gessain, Paul Vincent, Jean Bourgeois), nutrition (Jean Sutter), and housing (Jean Merlet), as well as the first polls (Jean Stoetzel). The foundation, which after the war became the INED demographics institute, employed 300 researchers from the summer of 1942 to the end of the autumn of 1944.[41] "The foundation was chartered as a public institution under the joint supervision of the ministries of finance and public health. It was given financial autonomy and a budget of forty million francs, roughly one franc per inhabitant: a true luxury considering the burdens imposed by the German Occupation on the nation's resources. By way of comparison, the whole Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) was given a budget of fifty million francs."[40]

Alexis Carrel had previously published in 1935 the best-selling book L'Homme, cet inconnu ("Man, This Unknown"). Since the early 1930s, Carrel had advocated the use of gas chambers to rid humanity of its "inferior stock"[citation needed], endorsing the scientific racism discourse[citation needed]. One of the founders of these pseudoscientifical theories had been Arthur de Gobineau in his 1853–1855 essay titled An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races.[citation needed] In the 1936 preface to the German edition of his book, Alexis Carrel had added a praise to the eugenics policies of the Third Reich, writing that:

(t)he German government has taken energetic measures against the propagation of the defective, the mentally diseased, and the criminal. The ideal solution would be the suppression of each of these individuals as soon as he has proven himself to be dangerous.[42]

Carrel also wrote in his book that:

(t)he conditioning of petty criminals with the whip, or some more scientific procedure, followed by a short stay in hospital, would probably suffice to insure order. Those who have murdered, robbed while armed with automatic pistol or machine gun, kidnapped children, despoiled the poor of their savings, misled the public in important matters, should be humanely and economically disposed of in small euthanasic institutions supplied with proper gasses. A similar treatment could be advantageously applied to the insane, guilty of criminal acts.[43]

Alexis Carrel had also taken an active part to a symposium in Pontigny organized by Jean Coutrot, the "Entretiens de Pontigny".[citation needed] Scholars such as Lucien Bonnafé, Patrick Tort and Max Lafont have accused Carrel of responsibility for the execution of thousands of mentally ill or impaired patients under Vichy.[citation needed]

Statute on Jews

A Nazi ordinance dated 21 September 1940, forced Jews of the "occupied zone" to declare themselves as such at a police station or sub-prefectures (sous-préfectures). Under the responsibility of André Tulard, head of the Service on Foreign Persons and Jewish Questions at the Prefecture of Police of Paris, a filing system registering Jewish people was created. Tulard had previously created such a filing system under the Third Republic, registering members of the Communist Party (PCF). In the department of the Seine, encompassing Paris and its immediate suburbs, nearly 150,000 persons, unaware of the upcoming danger and assisted by the police, presented themselves at police stations in accordance with the military order. The registered information was then centralized by the French police, who constructed, under the direction of inspector Tulard, a central filing system. According to the Dannecker report, "this filing system is subdivided into files alphabetically classed, Jewish with French nationality and foreign Jewish having files of different colours, and the files were also classed, according to profession, nationality and street [of residency]"[44]). These files were then handed over to Theodor Dannecker, head of the Gestapo in France, under the orders of Adolf Eichmann, head of the RSHA IV-D. They were used by the Gestapo on various raids, among them the August 1941 raid in the 11th arrondissement of Paris, which resulted in 3,200 foreign and 1,000 French Jews being interned in various camps, including Drancy.

On 3 October 1940, the Vichy government voluntarily promulgated the first Statute on Jews, which created a special underclass of French Jewish citizens, and enforced, for the first time in France, racial segregation.[45] The October 1940 Statute excluded Jews from the administration, the armed forces, entertainment, arts, media, and certain professions, such as teaching, law, and medicine. A Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs (CGQJ, Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives) was created on 29 March 1941. It was directed by Xavier Vallat until May 1942, and then by Darquier de Pellepoix until February 1944. Mirroring the Reich Association of Jews, the Union Générale des Israélites de France was founded.

The police oversaw the confiscation of telephones and radios from Jewish homes and enforced a curfew on Jews starting in February 1942. They also enforced requirements that Jews not appear in public places, and ride only on the last car of the Parisian metro.

Along with many French police officials, André Tulard was present on the day of the inauguration of Drancy internment camp in 1941, which was used largely by French police as the central transit camp for detainees captured in France. All Jews and others "undesirables" passed through Drancy before heading to Auschwitz and other camps.

July 1942 Vel' d'Hiv Roundup

In July 1942, under German orders, the French police organized the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup (Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv) under orders by René Bousquet and his second in Paris, Jean Leguay with cooperation from authorities of the SNCF, the state railway company. The police arrested 13,152 Jews, including 4,051 children—which the Gestapo had not asked for—and 5,082 women on 16 and 17 July, and imprisoned them in the Winter Velodrome in unhygienic conditions. They were led to Drancy internment camp (run by Nazi Alois Brunner, who is still wanted for crimes against humanity, and French constabulary police), then crammed into box cars and shipped by rail to Auschwitz. Most of the victims died en route due to lack of food or water. The remaining survivors were sent to the gas chambers. This action alone represented more than a quarter of the 42,000 French Jews sent to concentration camps in 1942, of which only 811 would return after the end of the war. Although the Nazi VT (Verfügungstruppe) had initially directed the action, French police authorities vigorously participated. On 16 July 1995, President Jacques Chirac officially apologized for the participation of French police forces in the July 1942 raid. "There was no effective police resistance until the end of Spring of 1944", wrote historians Jean-Luc Einaudi and Maurice Rajsfus.[46]

August 1942 and January 1943 raids

The French police, headed by Bousquet, arrested 7,000 Jews in the southern zone in August 1942. 2,500 of them transited through the Camp des Milles near Aix-en-Provence before joining Drancy. Then, on 22, 23 and 24 January 1943, assisted by Bousquet's police force, the Germans organized a raid in Marseilles. During the Battle of Marseilles, the French police checked the identity documents of 40,000 people, and the operation succeeded in sending 2,000 Marseillese people in the death trains, leading to the extermination camps. The operation also encompassed the expulsion of an entire neighborhood (30,000 persons) in the Old Port before its destruction. For this occasion, SS-Gruppenführer Karl Oberg, in charge of the German Police in France, made the trip from Paris, and transmitted to Bousquet orders directly received from Heinrich Himmler. It is another notable case of the French police's willful collaboration with the Nazis.[47]

French collaborationnistes and collaborators

Stanley Hoffmann in 1974,[48] and after him, other historians such as Robert Paxton and Jean-Pierre Azéma have used the term collaborationnistes to refer to fascists and Nazi sympathisers who, for ideological reasons, wished a reinforced collaboration with Hitler's Germany. Examples of these are Parti Populaire Français (PPF) leader Jacques Doriot, writer Robert Brasillach or Marcel Déat. A principal motivation and ideological foundation among collaborationnistes was anticommunism.[48]

Organizations such as La Cagoule opposed the Third Republic, particularly when the left-wing Popular Front was in power.

Collaborationists may have influenced the Vichy government's policies, but ultra-collaborationists never comprised the majority of the government before 1944.[49]

In order to enforce the régime's will, some paramilitary organizations were created. A notable example was the "Légion Française des Combattants" (LFC) (French Legion of Fighters), including at first only former combatants, but quickly adding "Amis de la Légion" and cadets of the Légion, who had never seen battle, but who supported Pétain's régime. The name was then quickly changed to "Légion Française des Combattants et des volontaires de la Révolution Nationale" (French Legion of Fighters and Volunteers of the National Revolution). Joseph Darnand created a "Service d'Ordre Légionnaire" (SOL), which consisted mostly of French supporters of the Nazis, of which Pétain fully approved.

Relationships with the Allied powers

- The United Kingdom, shortly after the Armistice (22 June 1940), attacked a large French naval contingent in Mers-el-Kebir, killing 1,297 French military personnel. Vichy severed diplomatic relations. Britain feared that the French naval fleet could wind up in German hands and be used against its own naval forces, which were so vital to maintaining north Atlantic shipping and communications. Under the armistice, France had been allowed to retain the French Navy, the Marine Nationale, under strict conditions. Vichy pledged that the fleet would never fall into the hands of Germany, but refused to send the fleet beyond Germany's reach by sending it to Britain or to far away territories of the French empire such as the West Indies. This did not satisfy Winston Churchill, who ordered French ships in British ports to be seized by the Royal Navy. The French squadron at Alexandria, under Admiral René-Emile Godfroy, was effectively interned until 1943 after an agreement was reached with Admiral Andrew Browne Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet.

- Due to British requests and the sensitivities of its French Canadian population, Canada maintained full diplomatic relations with the Vichy Regime until the beginning of November 1942 and Case Anton – the complete occupation of Vichy France by the Nazis.[50]

- Australia maintained full diplomatic relations with the Vichy Regime until the end of the war, and also entered into full diplomatic relations with the Free French.[51]

- The Soviet Union maintained full diplomatic relations with the Vichy Regime until 30 June 1941. These were broken after Vichy supported Operation Barbarossa.

- The United States granted Vichy full diplomatic recognition, sending Admiral William D. Leahy to France as American ambassador. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull hoped to use American influence to encourage those elements in the Vichy government opposed to military collaboration with Germany. The Americans also hoped to encourage Vichy to resist German war demands, such as for air bases in French-mandated Syria or to move war supplies through French territories in North Africa. The essential American position was that France should take no action not explicitly required by the armistice terms that could adversely affect Allied efforts in the war.

The US position towards Vichy France and De Gaulle was especially hesitant and inconsistent. President Roosevelt disliked Charles de Gaulle, whom he regarded as an "apprentice dictator."[52] Robert Murphy, Roosevelt's representative in North Africa, started preparing the landing in North Africa from December 1940 (i.e. a year before the US entered the war). The US first tried to support General Maxime Weygand, general delegate of Vichy for Africa until December 1941. This first choice having failed, they turned to Henri Giraud shortly before the landing in North Africa on 8 November 1942. Finally, after François Darlan's turn towards the Free Forces – Darlan had been president of Council of Vichy from February 1941 to April 1942 – they played him against de Gaulle. US General Mark W. Clark of the combined Allied command made Admiral Darlan sign on 22 November 1942 a treaty putting "North Africa at the disposition of the Americans" and making France "a vassal country."[52] Washington then imagined, between 1941 and 1942, a protectorate status for France, which would be submitted after the Liberation to an Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories (AMGOT) like Germany. After the assassination of Darlan on 24 December 1942, Washington turned again towards Henri Giraud, to whom had rallied Maurice Couve de Murville, who had financial responsibilities in Vichy, and Lemaigre-Dubreuil, a former member of La Cagoule and entrepreneur, as well as Alfred Pose, general director of the Banque nationale pour le commerce et l'industrie (National Bank for Trade and Industry).[52]

Creation of the Free French Forces

To counter the Vichy regime, General Charles de Gaulle created the Free French Forces (FFL) after his Appeal of 18 June 1940 radio speech. Initially, Winston Churchill was ambivalent about de Gaulle and he dropped ties with Vichy only when it became clear they would not fight. Even so, the Free France headquarters in London was riven with internal divisions and jealousies.

The additional participation of Free French forces in the Syrian operation was controversial within Allied circles. It raised the prospect of Frenchmen shooting at Frenchmen, raising fears of a civil war. Additionally, it was believed that the Free French were widely reviled within Vichy military circles, and that Vichy forces in Syria were less likely to resist the British if they were not accompanied by elements of the Free French. Nevertheless, de Gaulle convinced Churchill to allow his forces to participate, although de Gaulle was forced to agree to a joint British and Free French proclamation promising that Syria and Lebanon would become fully independent at the end of the war.

However, there were still French naval ships under Vichy French control. A large squadron was in port at Mers El Kébir harbour near Oran. Vice Admiral Somerville, with Force H under his command, was instructed to deal with the situation in July 1940. Various terms were offered to the French squadron, but all were rejected. Consequently, Force H opened fire on the French ships. Nearly 1,000 French sailors died when the Bretagne blew up in the attack. Less than two weeks after the armistice, Britain had fired upon forces of its former ally. The result was shock and resentment towards the UK within the French Navy, and to a lesser extent in the general French public.

Social and economic history

Vichy authorities were strongly opposed to "modern" social trends and tried through "national regeneration" to restore behavior more in line with traditional Catholicism.

Economy

Vichy rhetoric exalted the skilled laborer and small businessman. In practice, however, the needs of artisans for raw materials was neglected in favor of large businesses.[53] The General Committee for the Organization of Commerce (CGOC) was a national program to modernize and professionalize small business.[54]

In 1940 the government took direct control of all production, which was synchronized with the demands of the Germans. It replaced free trade unions with compulsory state unions that dictated labor policy without regard to the voice or needs of the workers. The centralized, bureaucratic control of the French economy was not a success, as German demands grew heavier and more unrealistic, passive resistance and inefficiencies multiplied, and Allied bombers hit the rail yards; however, Vichy made the first comprehensive long-range plans for the French economy. The government had never before attempted a comprehensive overview. De Gaulle's Provisional Government in 1944–45, quietly used the Vichy plans as a base for its own reconstruction program. The Monnet Plan of 1946 was closely based on Vichy plans.[55] Thus both teams of wartime and early postwar planners repudiated prewar laissez-faire practices and embraced the cause of drastic economic overhaul and a planned economy.[56]

Forced labor

Nazi Germany kept the French POWs as forced laborers throughout the war. They added compulsory (and volunteer) workers from occupied nations, especially in metal factories. The shortage of volunteers led the Vichy government to pass a law in September 1942 that effectively deported workers to Germany, where, they constituted 15% of the labor force by August 1944. The largest number worked in the giant Krupp steel works in Essen. Low pay, long hours, frequent bombings, and crowded air raid shelters added to the unpleasantness of poor housing, inadequate heating, limited food, and poor medical care, all compounded by harsh Nazi discipline. They finally returned home in the summer of 1945.[57] The forced labor draft encouraged the French Resistance and undermined the Vichy government.[58]

Food shortages

Civilians suffered shortages of all varieties of consumer goods.[59] The rationing system was stringent but badly mismanaged, leading to produced malnourishment, black markets, and hostility to state management of the food supply. The Germans seized about 20% of the French food production, which caused severe disruption to the household economy of the French people.[60] French farm production fell in half because of lack of fuel, fertilizer and workers; even so the Germans seized half the meat, 20 percent of the produce, and 2 percent of the champagne.[61] Supply problems quickly affected French stores which lacked most items. The government answered by rationing, but German officials set the policies and hunger prevailed, especially affecting youth in urban areas. The queues lengthened in front of shops. Some people—including German soldiers—benefited from the black market, where food was sold without tickets at very high prices. Farmers especially diverted meat to the black market, which meant that much less for the open market. Counterfeit food tickets were also in circulation. Direct buying from farmers in the countryside and barter against cigarettes became common. These activities were strictly forbidden, however, and thus carried out at the risk of confiscation and fines. Food shortages were most acute in the large cities. In the more remote country villages, however, clandestine slaughtering, vegetable gardens and the availability of milk products permitted better survival. The official ration provided starvation level diets of 1300 or fewer calories a day, supplemented by home gardens and, especially, black market purchases.[62]

Women

The 2 million French soldiers held as POWs and forced laborers in Germany throughout the war were not at risk of death in combat but the anxieties of separation for their 800,000 wives were high. The government provided a modest allowance, but one in ten became prostitutes to support their families.[63]

Meanwhile the Vichy regime promoted a highly traditional model of female roles.[64] The Révolution Nationale official ideology fostered the patriarchal family, headed by a man with a subservient wife who was devoted to her many children. It gave women a key symbolic role to carry out the national regeneration. It used propaganda, women's organizations, and legislation to promote maternity, patriotic duty, and female submission to marriage, home, and children's education.[59] The falling birthrate appeared to be a grave problem to Vichy. It introduced family allowances and opposed birth control and abortion. Conditions were very difficult for housewives, as food was short as well as most necessities.[65] Mother's Day became a major date in the Vichy calendar, with festivities in the towns and schools featuring the award of medals to mothers of numerous children. Divorce laws were made much more stringent, and restrictions were placed on the employment of married women. Family allowances that had begun in the 1930s were continued, and became a vital lifeline for many families; it was a monthly cash bonus for having more children. In 1942 the birth rate started to rise, and by 1945 it was higher than it had been for a century.[ 1]:331–332

On the other side women of the Resistance, many of whom were associated with combat groups linked to the French Communist Party (PCF), broke the gender barrier by fighting side by side with men. After the war, their services were ignored, but France did give women the vote in 1944.[66]

French colonies and Vichy

In Central Africa, three of the four colonies in French Equatorial Africa went over to the Free French almost immediately, Chad on 26 August 1940, French Congo on 29 August 1940, and Ubangi-Shari on 30 August 1940. They were joined by the separate colony of Cameroon on 27 August 1940. The final colony in French Equatorial Africa, Gabon, had to be occupied by military force between 27 October and 12 November 1940.[67] In time, the majority of the colonies tended to switch to the Allied side peacefully in response to persuasion and to changing events. This did not, however, happen overnight: Guadeloupe and Martinique in the West Indies, as well as French Guiana on the northern coast of South America, did not join the Free French until 1943. Meanwhile, France's Arab colonies (Syria, Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco) generally remained under Vichy control until captured by Allied forces. This was chiefly because their proximity to Europe made them easier to maintain without Allied interference; this same proximity also gave them strategic importance for the European theater of the war. Conversely, more remote French possessions sided with the Free French Forces early, whether upon Free French action such as in Saint Pierre and Miquelon (despite U.S. wishes to the contrary) or spontaneously such as in French Polynesia.

Conflicts with Britain in Mers-el-Kebir, Dakar, Gibraltar, Libreville, Syria, and Madagascar

Relations between the United Kingdom and the Vichy government were difficult. The Vichy government broke off diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom on 5 July 1940, after the Royal Navy attacked the French fleet in port at Mers-el-Kebir, Algeria in order to deny the possibility their use by Germany. The destruction of the fleet followed a standoff during which the British insisted that the French either scuttle their vessels, sail to a neutral port or join them in the war against Germany. These options were refused and the fleet was destroyed. This move by Britain hardened relations between the two former allies and caused more of the French population to side with Vichy against the British-supported Free French.[68]

On 23 September 1940, the British Royal Navy and Free French forces under General De Gaulle launched Operation Menace, an attempt to seize the strategic, Vichy-held port of Dakar in French West Africa (modern Senegal). After attempts to encourage them to join the allies were rebuffed by the defenders, a sharp fight erupted between Vichy and Allied forces. HMS Resolution was heavily damaged by torpedoes, and Free French troops landing at a beach south of the port were driven off by heavy fire. Even worse from a strategic point of view, bombers of the Vichy French Air Force (Armée de l'Air de Vichy) based in North Africa began bombing the British base at Gibraltar in response to the attack on Dakar. Shaken by the resolute Vichy defense, and not wanting to further escalate the conflict, British and Free French forces withdrew on 25 September, bringing the battle to an end.

On 8 November 1940, Free French forces under the command of Charles de Gaulle and Pierre Koenig, along with the assistance of the British Royal Navy, invaded Vichy held Gabon. Gabon, which was the only territory of French Equatorial Africa that was unwilling to join the Free French Forces, fell into allied hands on 12 November 1940, after the capital Libreville was bombed and captured. The final Vichy troops in Gabon surrendered without any military confrontation with the allies at Port-Gentil. The capture of Gabon by the Allies was crucial for ensuring that the entire French Equatorial Africa was out of Axis reach.

The next flashpoint between Britain and Vichy France came when a revolt in Iraq was put down by British forces in June 1941. German Air Force (Luftwaffe) and Italian Air Force (Regia Aeronautica) aircraft, staging through the French possession of Syria, intervened in the fighting in small numbers. That highlighted Syria as a threat to British interests in the Middle East. Consequently, on 8 June, British and Commonwealth forces invaded Syria and Lebanon. This was known as the Syria-Lebanon campaign or Operation Exporter. The Syrian capital, Damascus, was captured on 17 June and the five-week campaign ended with the fall of Beirut and the Convention of Acre (Armistice of Saint Jean d'Acre) on 14 July 1941.

From 5 May to 6 November 1942 British and Commonwealth forces conducted Operation Ironclad, the seizure of the large, Vichy French-controlled island of Madagascar, which the British feared Japanese forces might use as a base to disrupt trade and communications in the Indian Ocean. The initial landing at Diégo-Suarez was relatively quick, though it took British forces a further six months to gain control of the entire island.

Indochina

In June 1940 the Fall of France made the French hold on Indochina tenuous. The isolated colonial administration, led by Patrick He, was cut off from outside help and outside supplies. After negotiations with Japan the French allowed the Japanese to set up military bases in Indochina.[69]

This seemingly subservient behavior convinced the regime of Major-General Plaek Pibulsonggram, the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand, that Vichy France would not seriously resist a confrontation with Thailand. In October 1940, the military forces of Thailand attacked across the border with Indochina and launched the Franco-Thai War. Though the French won an important naval victory over the Thais, the Japanese forced the French to accept their mediation of a peace treaty that returned parts of Cambodia and Laos that had been taken from Thailand around the start of the 20th century to Thai control. This territorial loss was a major blow to French pride, especially since the ruins of Angkor Wat, of which the French were especially proud, were located in the region of Cambodia returned to Thailand.

The French were left in place to administer the rump colony until 9 March 1945, when the Japanese staged a coup d'état in French Indochina and took control of Indochina establishing their own colony, the Empire of Vietnam, as a double puppet state.

India

Until 1962, France possessed four small non-contiguous but politically united colonies across India, the largest being located in Southeast India, Pondicherry. Immediately after the fall of France, the Governor General of French India, Louis Alexis Étienne Bonvin, declared the French colonies in India would continue to fight with its British allies. Free French forces participated in the Western Desert campaign, although news of the death of French-Indian soldiers caused some disturbances in Pondicherry.

French Somaliland

During the Italian invasion and occupation of Ethiopia in the mid-1930s and during the early stages of World War II, constant border skirmishes occurred between the forces in French Somaliland and the forces in Italian East Africa. After the Fall of France in 1940, French Somaliland declared loyalty to Vichy France. The colony remained loyal to Vichy France during the East African Campaign but stayed out of that conflict. This lasted until December 1942. By that time, the Italians had been defeated and the French colony was isolated by a British blockade. Free French and Allied forces recaptured the colony's capital of Djibouti at the end of 1942. A local battalion from Djibouti participated in the liberation of France in 1944.

French North Africa

Operation Torch was the American and British invasion of French North Africa, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, started on 8 November 1942, with landings in Morocco and Algeria. The long-term goal was to clear Germany and Italy from North Africa, enhance naval control of the Mediterranean, and prepare an invasion of Italy in 1943. The Vichy forces resisted briefly, then under the leadership of Vichy Admiral Darlan (who happened to be on the scene), cooperated with the Allies. The Allies recognized Darlan's self-nomination as High Commissioner of France (head of civil government) for North and West Africa. He ordered Vichy forces there to cease resisting and cooperate with the Allies, and they did so. By the time the Tunisia Campaign was fought, the French forces in North Africa had gone over to the Allied side, joining the Free French Forces.[70][71]

Oceania

The French possessions in Oceania joined the Free French side in 1940, or in one case in 1942. They then served as bases for the Allied effort in the Pacific and contributed troops to the Free French Forces.[72]

New Hebrides

In the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), then a French-British condominium, Resident Commissioner Henri Sautot quickly led the French community to join the Free French side. The outcome was decided by a combination of patriotism and economic opportunism in the expectation independence would result.[73][74]

French Polynesia

Following the Appeal of 18 June, debate arose among the population of French Polynesia. A referendum was organized on 2 September 1940 in Tahiti and Moorea, with outlying islands reporting agreement in following days. The vote was 5564 to 18 in favor of joining the Free French side.[75] Following the Attack on Pearl Harbor, American forces identified French Polynesia as an ideal refuelling point between Hawaii and Australia and, with de Gaulle's agreement, organized "Operation Bobcat" sending nine ships with 5,000 GIs who built a naval refuelling base and airstrip and set up coastal defense guns on Bora Bora.[76] This first experience was valuable in later Seabee efforts in the Pacific, and the Bora Bora base supplied the Allied ships and planes that fought the Battle of the Coral Sea. Troops from French Polynesia and New Caledonia formed a Bataillon du Pacifique in 1940; became part of the 1st Free French Division in 1942, distinguishing themselves during the Battle of Bir Hakeim and subsequently combining with another unit to form the Bataillon d'infanterie de marine et du Pacifique; fought in the Italian Campaign, distinguishing itself at the Garigliano during the Battle of Monte Cassino and on to Tuscany; and participated in the Provence landings and onwards to the liberation of France.[77][78]

Wallis and Futuna

In Wallis and Futuna the local administrator and bishop sided with Vichy, but faced opposition from some of the population and clergy; their attempts at naming a local king in 1941 (to buffer the territory from their opponents) backfired as the newly elected king refused to declare allegiance to Pétain. The situation stagnated for a long while, due to the great remoteness of the islands and the fact that no overseas ship visited the islands for 17 months after January 1941. An aviso sent from Nouméa took over Wallis on behalf of the Free French on 27 May 1942, and Futuna on 29 May 1942. This allowed American forces to build an airbase and seaplane base on Wallis (Navy 207) that served the Allied Pacific operations.[79]

New Caledonia

In New Caledonia Henri Sautot again led prompt allegiance to the Free French side, effective 19 September 1940.[80] Due to its location on the edge of the Coral Sea and on the flank of Australia, New Caledonia became strategically critical in the effort to combat the Japanese advance in the Pacific in 1941–1942 and to protect the sea lanes between North America and Australia. Nouméa served as a headquarters of the United States Navy and Army in the South Pacific,[81] and as a repair base for Allied vessels. New Caledonia contributed personnel both to the Bataillon du Pacifique and to the Free French Naval Forces that saw action in the Pacific and Indian Ocean.

German invasion, November 1942 and decline of the Vichy regime

Hitler ordered Case Anton to occupy Corsica and then the rest of unoccupied southern zone in immediate reaction to the landing of the Allies in North Africa (Operation Torch) on 8 November 1942. Following the conclusion of the operation on 12 November, Vichy's remaining military forces were disbanded. Vichy continued to exercise its remaining jurisdiction over almost all of metropolitan France, with the residual power devolved into the hands of Laval, until the gradual collapse of the regime following the Allied invasion in June 1944. On 7 September 1944, following the Allied invasion of France, the remainders of the Vichy government cabinet fled to Germany and established a puppet government in exile at Sigmaringen. That rump government finally fell when the city was taken by the Allied French army in April 1945.

Part of the residual legitimacy of the Vichy regime resulted from the continued ambivalence of U.S. and British leaders. President Roosevelt continued to cultivate Vichy, and promoted General Henri Giraud as a preferable alternative to de Gaulle, despite the poor performance of Vichy forces in North Africa—Admiral François Darlan had landed in Algiers the day before Operation Torch. Algiers was headquarters of the Vichy French XIX Army Corps, which controlled Vichy military units in North Africa. Darlan was neutralized within 15 hours by a 400-strong French resistance force. Roosevelt and Churchill accepted Darlan, rather than de Gaulle, as the French leader in North Africa. De Gaulle had not even been informed of the landing in North Africa.[82] The United States also resented the Free French taking control of St Pierre and Miquelon on 24 December 1941, because, Secretary of State Hull believed, it interfered with a U.S.-Vichy agreement to maintain the status quo with respect to French territorial possessions in the western hemisphere.

Following the invasion of France via Normandy and Provence (Operation Overlord and Operation Dragoon) and the departure of the Vichy leaders, the U.S., Britain and the Soviet Union finally recognized the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF), headed by de Gaulle, as the legitimate government of France on 23 October 1944. Before that, the first return of democracy to mainland France since 1940 had occurred with the declaration of the Free Republic of Vercors on 3 July 1944, at the behest of the Free French government—but that act of resistance was quashed by an overwhelming German attack by the end of July.

North Africa

In North Africa, after 8 November 1942 putsch by the French resistance, most Vichy figures were arrested (including General Alphonse Juin, chief commander in North Africa, and Admiral François Darlan). However, Darlan was released and U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower finally accepted his self-nomination as high commissioner of North Africa and French West Africa (Afrique occidentale française, AOF), a move that enraged de Gaulle, who refused to recognize Darlan's status. After Darlan signed an armistice with the Allies and took power in North Africa, Germany violated the 1940 armistice and invaded Vichy France on 10 November 1942 (operation code-named Case Anton), triggering the scuttling of the French fleet in Toulon.

Giraud arrived in Algiers on 10 November, and agreed to subordinate himself to Admiral Darlan as the French African army commander. Even though he was now in the Allied camp, Darlan maintained the repressive Vichy system in North Africa, including concentration camps in southern Algeria and racist laws. Detainees were also forced to work on the Transsaharien railroad. Jewish goods were "aryanized" (i.e., stolen), and a special Jewish Affair service was created, directed by Pierre Gazagne. Numerous Jewish children were prohibited from going to school, something which not even Vichy had implemented in metropolitan France.[82] The admiral was killed on 24 December 1942, in Algiers by the young monarchist Bonnier de La Chapelle. Although de la Chapelle had been a member of the resistance group led by Henri d'Astier de La Vigerie, it is believed he was acting as an individual.

After Admiral Darlan's assassination, Giraud became his de facto successor in French Africa with Allied support. This occurred through a series of consultations between Giraud and de Gaulle. The latter wanted to pursue a political position in France and agreed to have Giraud as commander in chief, as the more qualified military person of the two. It is questionable that he ordered that many French resistance leaders who had helped Eisenhower's troops be arrested, without any protest by Roosevelt's representative, Robert Murphy. Later, the Americans sent Jean Monnet to counsel Giraud and to press him into repeal the Vichy laws. After difficult negotiations, Giraud agreed to suppress the racist laws, and to liberate Vichy prisoners of the South Algerian concentration camps. The Cremieux decree, which granted French citizenship to Jews in Algeria and which had been repealed by Vichy, was immediately restored by General de Gaulle.

Giraud took part in the Casablanca conference, with Roosevelt, Churchill and de Gaulle, in January 1943. The Allies discussed their general strategy for the war, and recognized joint leadership of North Africa by Giraud and de Gaulle. Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle then became co-presidents of the Comité français de la Libération Nationale, which unified the Free French Forces and territories controlled by them and had been founded at the end of 1943. Democratic rule was restored in French Algeria, and the Communists and Jews liberated from the concentration camps.[82]

At the end of April 1945 Pierre Gazagne, secretary of the general government headed by Yves Chataigneau, took advantage of his absence to exile anti-imperialist leader Messali Hadj and arrest the leaders of his party, the Algerian People's Party (PPA).[82] On the day of the Liberation of France, the GPRF would harshly repress a rebellion in Algeria during the Sétif massacre of 8 May 1945, which has been qualified by some historians as the "real beginning of the Algerian War".[82]

Independence of the SOL

In 1943 the Service d'ordre légionnaire (SOL) collaborationist militia, headed by Joseph Darnand, became independent and was transformed into the "Milice française" (French Militia). Officially directed by Pierre Laval himself, the SOL was led by Darnand, who held an SS rank and pledged an oath of loyalty to Adolf Hitler. Under Darnand and his sub-commanders, such as Paul Touvier and Jacques de Bernonville, the Milice was responsible for helping the German forces and police in the repression of the French Resistance and Maquis.

In addition, the Milice participated with area Gestapo head Klaus Barbie in seizing members of the resistance and minorities including Jews for shipment to detention centres, such as the Drancy deportation camp, en route to Auschwitz, and other German concentration camps, including Dachau and Buchenwald.

Jewish death toll

In 1940 approximately 350,000 Jews lived in metropolitan France, less than half of them with French citizenship (and the others foreigners, mostly exiles from Germany during the 1930s).[83] About 200,000 of them, and the large majority of foreign Jews, resided in Paris and its outskirts. Among the 150,000 French Jews, about 30,000, generally native from Central Europe, had been naturalized French during the 1930s. Of the total, approximately 25,000 French Jews and 50,000 foreign Jews were deported.[84] According to historian Robert Paxton, 76,000 Jews were deported and died in concentration and extermination camps. Including the Jews who died in concentration camps in France, this would have made for a total figure of 90,000 Jewish deaths (a quarter of the total Jewish population before the war, by his estimate).[85] Paxton's numbers imply that 14,000 Jews died in French concentration camps. However, the systematic census of Jewish deportees from France (citizens or not) drawn under Serge Klarsfeld concluded that 3,000 had died in French concentration camps and 1,000 more had been shot. Of the approximately 76,000 deported, 2,566 survived. The total thus reported is slightly below 77,500 dead (somewhat less than a quarter of the Jewish population in France in 1940).[86]