Venture capital

and venture capital | |

| |

|

Early history | |

| | |

Venture capital (VC) is financial capital provided to early-stage, high-potential, high risk, growth startup companies. The venture capital fund makes money by owning equity in the companies it invests in, which usually have a novel technology or business model in high technology industries, such as biotechnology, IT and software. The typical venture capital investment occurs after the seed funding round as the first round of institutional capital to fund growth (also referred to as Series A round) in the interest of generating a return through an eventual realization event, such as an IPO or trade sale of the company. Venture capital is a subset of private equity. Therefore, all venture capital is private equity, but not all private equity is venture capital.[1]

In addition to angel investing and other seed funding options, venture capital is attractive for new companies with limited operating history that are too small to raise capital in the public markets and have not reached the point where they are able to secure a bank loan or complete a debt offering. In exchange for the high risk that venture capitalists assume by investing in smaller and less mature companies, venture capitalists usually get significant control over company decisions, in addition to a significant portion of the company's ownership (and consequently value).

Venture capital is also associated with job creation (accounting for 2% of US GDP),[2] the knowledge economy, and used as a proxy measure of innovation within an economic sector or geography. Every year, there are nearly 2 million businesses created in the USA, and 600–800 get venture capital funding. According to the National Venture Capital Association, 11% of private sector jobs come from venture backed companies and venture backed revenue accounts for 21% of US GDP.[3]

It is also a way in which public and private sectors can construct an institution that systematically creates networks for the new firms and industries, so that they can progress. This institution helps in identifying and combining pieces of companies, like finance, technical expertise, know-hows of marketing and business models. Once integrated, these enterprises succeed by becoming nodes in the search networks for designing and building products in their domain.[4]

History

A venture may be defined as a project prospective converted into a process with an adequate assumed risk and investment. With few exceptions, private equity in the first half of the 20th century was the domain of wealthy individuals and families. The Wallenbergs, Vanderbilts, Whitneys, Rockefellers, and Warburgs were notable investors in private companies in the first half of the century. In 1938, Laurance S. Rockefeller helped finance the creation of both Eastern Air Lines and Douglas Aircraft, and the Rockefeller family had vast holdings in a variety of companies. Eric M. Warburg founded E.M. Warburg & Co. in 1938, which would ultimately become Warburg Pincus, with investments in both leveraged buyouts and venture capital. The Wallenberg family started Investor AB in 1916 in Sweden and were early investors in several Swedish companies such as ABB, Atlas Copco, Ericsson, etc. in the first half of the 20th century.

Origins of modern private equity

Before World War II, money orders (originally known as "development capital") were primarily the domain of wealthy individuals and families. It was not until after World War II that what is considered today to be true private equity investments began to emerge marked by the founding of the first two venture capital firms in 1946: American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC) and J.H. Whitney & Company.[5][6]

ARDC was founded by Georges Doriot, the "father of venture capitalism"[7] (former dean of Harvard Business School and founder of INSEAD), with Ralph Flanders and Karl Compton (former president of MIT), to encourage private sector investments in businesses run by soldiers who were returning from World War II. ARDC's significance was primarily that it was the first institutional private equity investment firm that raised capital from sources other than wealthy families although it had several notable investment successes as well.[8] ARDC is credited with the first trick when its 1957 investment of $70,000 in Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) would be valued at over $355 million after the company's initial public offering in 1968 (representing a return of over 1200 times on its investment and an annualized rate of return of 101%).[9]

Former employees of ARDC went on and established several prominent venture capital firms including Greylock Partners (founded in 1965 by Charlie Waite and Bill Elfers) and Morgan, Holland Ventures, the predecessor of Flagship Ventures (founded in 1982 by James Morgan).[10] ARDC continued investing until 1971 with the retirement of Doriot. In 1972, Doriot merged ARDC with Textron after having invested in over 150 companies.

J.H. Whitney & Company was founded by John Hay Whitney and his partner Benno Schmidt. Whitney had been investing since the 1930s, founding Pioneer Pictures in 1933 and acquiring a 15% interest in Technicolor Corporation with his cousin Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney. By far Whitney's most famous investment was in Florida Foods Corporation. The company developed an innovative method for delivering nutrition to American soldiers, which later came to be known as Minute Maid orange juice and was sold to The Coca-Cola Company in 1960. J.H. Whitney & Company continues to make investments in leveraged buyout transactions and raised $750 million for its sixth institutional private equity fund in 2005.

Early venture capital and the growth of Silicon Valley

One of the first steps toward a professionally-managed venture capital industry was the passage of the Small Business Investment Act of 1958. The 1958 Act officially allowed the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) to license private "Small Business Investment Companies" (SBICs) to help the financing and management of the small entrepreneurial businesses in the United States.[11]

During the 1960s and 1970s, venture capital firms focused their investment activity primarily on starting and expanding companies. More often than not, these companies were exploiting breakthroughs in electronic, medical, or data-processing technology. As a result, venture capital came to be almost synonymous with technology finance. An early West Coast venture capital company was Draper and Johnson Investment Company, formed in 1962[12] by William Henry Draper III and Franklin P. Johnson, Jr. In 1965, Sutter Hill Ventures acquired the portfolio of Draper and Johnson as a founding action. Bill Draper and Paul Wythes were the founders, and Pitch Johnson formed Asset Management Company at that time.

It is commonly noted that the first venture-backed startup is Fairchild Semiconductor (which produced the first commercially practical integrated circuit), funded in 1959 by what would later become Venrock Associates.[13] Venrock was founded in 1969 by Laurance S. Rockefeller, the fourth of John D. Rockefeller's six children as a way to allow other Rockefeller children to develop exposure to venture capital investments.

It was also in the 1960s that the common form of private equity fund, still in use today, emerged. Private equity firms organized limited partnerships to hold investments in which the investment professionals served as general partner and the investors, who were passive limited partners, put up the capital. The compensation structure, still in use today, also emerged with limited partners paying an annual management fee of 1.0–2.5% and a carried interest typically representing up to 20% of the profits of the partnership.

The growth of the venture capital industry was fueled by the emergence of the independent investment firms on Sand Hill Road, beginning with Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield & Byers and Sequoia Capital in 1972. Located in Menlo Park, CA, Kleiner Perkins, Sequoia and later venture capital firms would have access to the many semiconductor companies based in the Santa Clara Valley as well as early computer firms using their devices and programming and service companies.[14]

Throughout the 1970s, a group of private equity firms, focused primarily on venture capital investments, would be founded that would become the model for later leveraged buyout and venture capital investment firms. In 1973, with the number of new venture capital firms increasing, leading venture capitalists formed the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA). The NVCA was to serve as the industry trade group for the venture capital industry.[15] Venture capital firms suffered a temporary downturn in 1974, when the stock market crashed and investors were naturally wary of this new kind of investment fund.

It was not until 1978 that venture capital experienced its first major fundraising year, as the industry raised approximately $750 million. With the passage of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) in 1974, corporate pension funds were prohibited from holding certain risky investments including many investments in privately held companies. In 1978, the US Labor Department relaxed certain of the ERISA restrictions, under the "prudent man rule,"[16] thus allowing corporate pension funds to invest in the asset class and providing a major source of capital available to venture capitalists.

1980s

The public successes of the venture capital industry in the 1970s and early 1980s (e.g., Digital Equipment Corporation, Apple Inc., Genentech) gave rise to a major proliferation of venture capital investment firms. From just a few dozen firms at the start of the decade, there were over 650 firms by the end of the 1980s, each searching for the next major "home run". The number of firms multiplied, and the capital managed by these firms increased from $3 billion to $31 billion over the course of the decade.[17]

The growth of the industry was hampered by sharply declining returns, and certain venture firms began posting losses for the first time. In addition to the increased competition among firms, several other factors impacted returns. The market for initial public offerings cooled in the mid-1980s before collapsing after the stock market crash in 1987 and foreign corporations, particularly from Japan and Korea, flooded early stage companies with capital.[17]

In response to the changing conditions, corporations that had sponsored in-house venture investment arms, including General Electric and Paine Webber either sold off or closed these venture capital units. Additionally, venture capital units within Chemical Bank and Continental Illinois National Bank, among others, began shifting their focus from funding early stage companies toward investments in more mature companies. Even industry founders J.H. Whitney & Company and Warburg Pincus began to transition toward leveraged buyouts and growth capital investments.[17][18][19]

Venture capital boom and the Internet Bubble

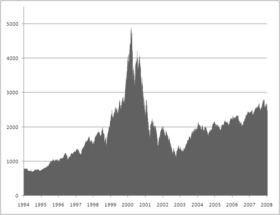

By the end of the 1980s, venture capital returns were relatively low, particularly in comparison with their emerging leveraged buyout cousins, due in part to the competition for hot startups, excess supply of IPOs and the inexperience of many venture capital fund managers. Growth in the venture capital industry remained limited throughout the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s, increasing from $3 billion in 1983 to just over $4 billion more than a decade later in 1994.

After a shakeout of venture capital managers, the more successful firms retrenched, focusing increasingly on improving operations at their portfolio companies rather than continuously making new investments. Results would begin to turn very attractive, successful and would ultimately generate the venture capital boom of the 1990s. Yale School of Management Professor Andrew Metrick refers to these first 15 years of the modern venture capital industry beginning in 1980 as the "pre-boom period" in anticipation of the boom that would begin in 1995 and last through the bursting of the Internet bubble in 2000.[20]

The late 1990s were a boom time for venture capital, as firms on Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park and Silicon Valley benefited from a huge surge of interest in the nascent Internet and other computer technologies. Initial public offerings of stock for technology and other growth companies were in abundance, and venture firms were reaping large returns.

Private equity crash

The Nasdaq crash and technology slump that started in March 2000 shook virtually the entire venture capital industry as valuations for startup technology companies collapsed. Over the next two years, many venture firms had been forced to write-off large proportions of their investments, and many funds were significantly "under water" (the values of the fund's investments were below the amount of capital invested). Venture capital investors sought to reduce size of commitments they had made to venture capital funds, and, in numerous instances, investors sought to unload existing commitments for cents on the dollar in the secondary market. By mid-2003, the venture capital industry had shriveled to about half its 2001 capacity. Nevertheless, PricewaterhouseCoopers's MoneyTree Survey[21] shows that total venture capital investments held steady at 2003 levels through the second quarter of 2005.

Although the post-boom years represent just a small fraction of the peak levels of venture investment reached in 2000, they still represent an increase over the levels of investment from 1980 through 1995. As a percentage of GDP, venture investment was 0.058% in 1994, peaked at 1.087% (nearly 19 times the 1994 level) in 2000 and ranged from 0.164% to 0.182% in 2003 and 2004. The revival of an Internet-driven environment in 2004 through 2007 helped to revive the venture capital environment. However, as a percentage of the overall private equity market, venture capital has still not reached its mid-1990s level, let alone its peak in 2000.

Venture capital funds, which were responsible for much of the fundraising volume in 2000 (the height of the dot-com bubble), raised only $25.1 billion in 2006, a 2%-decline from 2005 and a significant decline from its peak.[22]

Funding

Obtaining venture capital is substantially different from raising debt or a loan from a lender. Lenders have a legal right to interest on a loan and repayment of the capital, irrespective of the success or failure of a business. Venture capital is invested in exchange for an equity stake in the business. As a shareholder, the venture capitalist's return is dependent on the growth and profitability of the business. This return is generally earned when the venture capitalist "exits" by selling its shareholdings when the business is sold to another owner.

Venture capitalists are typically very selective in deciding what to invest in; as a rule of thumb, a fund may invest in one in four hundred opportunities presented to it,[citation needed] looking for the extremely rare, yet sought after, qualities, such as innovative technology, potential for rapid growth, a well-developed business model, and an impressive management team. Of these qualities, funds are most interested in ventures with exceptionally high growth potential, as only such opportunities are likely capable of providing the financial returns and successful exit event within the required timeframe (typically 3–7 years) that venture capitalists expect.

Because investments are illiquid and require the extended timeframe to harvest, venture capitalists are expected to carry out detailed due diligence prior to investment. Venture capitalists also are expected to nurture the companies in which they invest, in order to increase the likelihood of reaching an IPO stage when valuations are favourable. Venture capitalists typically assist at four stages in the company's development:[23]

- Idea generation;

- Start-up;

- Ramp up; and

- Exit

Because there are no public exchanges listing their securities, private companies meet venture capital firms and other private equity investors in several ways, including warm referrals from the investors' trusted sources and other business contacts; investor conferences and symposia; and summits where companies pitch directly to investor groups in face-to-face meetings, including a variant known as "Speed Venturing", which is akin to speed-dating for capital, where the investor decides within 10 minutes whether he wants a follow-up meeting. In addition, there are some new private online networks that are emerging to provide additional opportunities to meet investors.[24]

This need for high returns makes venture funding an expensive capital source for companies, and most suitable for businesses having large up-front capital requirements, which cannot be financed by cheaper alternatives such as debt. That is most commonly the case for intangible assets such as software, and other intellectual property, whose value is unproven. In turn, this explains why venture capital is most prevalent in the fast-growing technology and life sciences or biotechnology fields.

If a company does have the qualities venture capitalists seek including a solid business plan, a good management team, investment and passion from the founders, a good potential to exit the investment before the end of their funding cycle, and target minimum returns in excess of 40% per year, it will find it easier to raise venture capital.

Financing stages

There are typically six stages of venture round financing offered in Venture Capital, that roughly correspond to these stages of a company's development.[25]

- Seed funding: Low level financing needed to prove a new idea, often provided by angel investors. Crowd funding is also emerging as an option for seed funding.

- Start-up: Early stage firms that need funding for expenses associated with marketing and product development

- Growth (Series A round): Early sales and manufacturing funds

- Second-Round: Working capital for early stage companies that are selling product, but not yet turning a profit

- Expansion : Also called Mezzanine financing, this is expansion money for a newly profitable company

- Exit of venture capitalist : Also called bridge financing, 4th round is intended to finance the "going public" process

Between the first round and the fourth round, venture-backed companies may also seek to take venture debt.[26]

Firms and funds

Venture capitalists

A venture capitalist is a person who makes venture investments, and these venture capitalists are expected to bring managerial and technical expertise as well as capital to their investments. A venture capital fund refers to a pooled investment vehicle (in the United States, often an LP or LLC) that primarily invests the financial capital of third-party investors in enterprises that are too risky for the standard capital markets or bank loans. These funds are typically managed by a venture capital firm, which often employs individuals with technology backgrounds (scientists, researchers), business training and/or deep industry experience.

A core skill within VC is the ability to identify novel technologies that have the potential to generate high commercial returns at an early stage. By definition, VCs also take a role in managing entrepreneurial companies at an early stage, thus adding skills as well as capital, thereby differentiating VC from buy-out private equity, which typically invest in companies with proven revenue, and thereby potentially realizing much higher rates of returns. Inherent in realizing abnormally high rates of returns is the risk of losing all of one's investment in a given startup company. As a consequence, most venture capital investments are done in a pool format, where several investors combine their investments into one large fund that invests in many different startup companies. By investing in the pool format, the investors are spreading out their risk to many different investments versus taking the chance of putting all of their money in one start up firm.

Structure

Venture capital firms are typically structured as partnerships, the general partners of which serve as the managers of the firm and will serve as investment advisors to the venture capital funds raised. Venture capital firms in the United States may also be structured as limited liability companies, in which case the firm's managers are known as managing members. Investors in venture capital funds are known as limited partners. This constituency comprises both high net worth individuals and institutions with large amounts of available capital, such as state and private pension funds, university financial endowments, foundations, insurance companies, and pooled investment vehicles, called funds of funds.

Types

Venture Capitalist firms differ in their approaches. There are multiple factors, and each firm is different.

Some of the factors that influence VC decisions include:

- Business situation: Some VCs tend to invest in new ideas, or fledgling companies. Others prefer investing in established companies that need support to go public or grow.

- Some invest solely in certain industries.

- Some prefer operating locally while others will operate nationwide or even globally.

- VC expectations often vary. Some may want a quicker public sale of the company or expect fast growth. The amount of help a VC provides can vary from one firm to the next.

Roles

Within the venture capital industry, the general partners and other investment professionals of the venture capital firm are often referred to as "venture capitalists" or "VCs". Typical career backgrounds vary, but, broadly speaking, venture capitalists come from either an operational or a finance background. Venture capitalists with an operational background (operating partner) tend to be former founders or executives of companies similar to those which the partnership finances or will have served as management consultants. Venture capitalists with finance backgrounds tend to have investment banking or other corporate finance experience.

Although the titles are not entirely uniform from firm to firm, other positions at venture capital firms include:

| Position | Role |

|---|---|

| Venture partners | Venture partners are expected to source potential investment opportunities ("bring in deals") and typically are compensated only for those deals with which they are involved. |

| Principal | This is a mid-level investment professional position, and often considered a "partner-track" position. Principals will have been promoted from a senior associate position or who have commensurate experience in another field, such as investment banking, management consulting, or a market of particular interest to the strategy of the venture capital firm. |

| Associate | This is typically the most junior apprentice position within a venture capital firm. After a few successful years, an associate may move up to the "senior associate" position and potentially principal and beyond. Associates will often have worked for 1–2 years in another field, such as investment banking or management consulting. |

| Entrepreneur-in-residence | Entrepreneurs-in-residence (EIRs) are experts in a particular domain and perform due diligence on potential deals. EIRs are engaged by venture capital firms temporarily (six to 18 months) and are expected to develop and pitch startup ideas to their host firm although neither party is bound to work with each other. Some EIRs move on to executive positions within a portfolio company. |

Structure of the funds

Most venture capital funds have a fixed life of 10 years, with the possibility of a few years of extensions to allow for private companies still seeking liquidity. The investing cycle for most funds is generally three to five years, after which the focus is managing and making follow-on investments in an existing portfolio. This model was pioneered by successful funds in Silicon Valley through the 1980s to invest in technological trends broadly but only during their period of ascendance, and to cut exposure to management and marketing risks of any individual firm or its product.

In such a fund, the investors have a fixed commitment to the fund that is initially unfunded and subsequently "called down" by the venture capital fund over time as the fund makes its investments. There are substantial penalties for a limited partner (or investor) that fails to participate in a capital call.

It can take anywhere from a month or so to several years for venture capitalists to raise money from limited partners for their fund. At the time when all of the money has been raised, the fund is said to be closed, and the 10-year lifetime begins. Some funds have partial closes when one half (or some other amount) of the fund has been raised. The vintage year generally refers to the year in which the fund was closed and may serve as a means to stratify VC funds for comparison. This[27] shows the difference between a venture capital fund management company and the venture capital funds managed by them.

From investors' point of view, funds can be: (1) traditional—where all the investors invest with equal terms; or (2) asymmetric—where different investors have different terms. Typically the asymmetry is seen in cases where there's an investor that has other interests such as tax income in case of public investors.[28]

Compensation

Venture capitalists are compensated through a combination of management fees and carried interest (often referred to as a "two and 20" arrangement):

| Payment | Implementation |

|---|---|

| Management fees | an annual payment made by the investors in the fund to the fund's manager to pay for the private equity firm's investment operations.[29] In a typical venture capital fund, the general partners receive an annual management fee equal to up to 2% of the committed capital. |

| Carried interest | a share of the profits of the fund (typically 20%), paid to the private equity fund’s management company as a performance incentive. The remaining 80% of the profits are paid to the fund's investors[29] Strong limited partner interest in top-tier venture firms has led to a general trend toward terms more favorable to the venture partnership, and certain groups are able to command carried interest of 25–30% on their funds. |

Because a fund may run out of capital prior to the end of its life, larger venture capital firms usually have several overlapping funds at the same time; doing so lets the larger firm keep specialists in all stages of the development of firms almost constantly engaged. Smaller firms tend to thrive or fail with their initial industry contacts; by the time the fund cashes out, an entirely-new generation of technologies and people is ascending, whom the general partners may not know well, and so it is prudent to reassess and shift industries or personnel rather than attempt to simply invest more in the industry or people the partners already know.

Alternatives

Because of the strict requirements venture capitalists have for potential investments, many entrepreneurs seek seed funding from angel investors, who may be more willing to invest in highly speculative opportunities, or may have a prior relationship with the entrepreneur.

Furthermore, many venture capital firms will only seriously evaluate an investment in a start-up company otherwise unknown to them if the company can prove at least some of its claims about the technology and/or market potential for its product or services. To achieve this, or even just to avoid the dilutive effects of receiving funding before such claims are proven, many start-ups seek to self-finance sweat equity until they reach a point where they can credibly approach outside capital providers such as venture capitalists or angel investors. This practice is called "bootstrapping".

There has been some debate since the dot com boom that a "funding gap" has developed between the friends and family investments typically in the $0 to $250,000 range and the amounts that most VC funds prefer to invest between $1 million to $2 million.[citation needed] This funding gap may be accentuated by the fact that some successful VC funds have been drawn to raise ever-larger funds, requiring them to search for correspondingly larger investment opportunities. This gap is often filled by sweat equity and seed funding via angel investors as well as equity investment companies who specialize in investments in startup companies from the range of $250,000 to $1 million. The National Venture Capital Association estimates that the latter now invest more than $30 billion a year in the USA in contrast to the $20 billion a year invested by organized venture capital funds.[citation needed]

Crowd funding is emerging as an alternative to traditional venture capital. Crowd funding is an approach to raising the capital required for a new project or enterprise by appealing to large numbers of ordinary people for small donations. While such an approach has long precedents in the sphere of charity, it is receiving renewed attention from entrepreneurs such as independent film makers, now that social media and online communities make it possible to reach out to a group of potentially interested supporters at very low cost. Some crowd funding models are also being applied for startup funding such as those listed at Comparison of crowd funding services. One of the reasons to look for alternatives to venture capital is the problem of the traditional VC model. The traditional VCs are shifting their focus to later-stage investments, and return on investment of many VC funds have been low or negative.[24][30]

In Europe and India, Media for equity is a partial alternative to venture capital funding. Media for equity investors are able to supply start-ups with often significant advertising campaigns in return for equity.

In industries where assets can be securitized effectively because they reliably generate future revenue streams or have a good potential for resale in case of foreclosure, businesses may more cheaply be able to raise debt to finance their growth. Good examples would include asset-intensive extractive industries such as mining, or manufacturing industries. Offshore funding is provided via specialist venture capital trusts, which seek to utilise securitization in structuring hybrid multi-market transactions via an SPV (special purpose vehicle): a corporate entity that is designed solely for the purpose of the financing.

In addition to traditional venture capital and angel networks, groups have emerged, which allow groups of small investors or entrepreneurs themselves to compete in a privatized business plan competition where the group itself serves as the investor through a democratic process.[31]

Law firms are also increasingly acting as an intermediary between clients seeking venture capital and the firms providing it.[32]

Other forms include Venture Resources, that seek to provide non-monitary support to launch a new venture.

Geographical differences

Venture capital, as an industry, originated in the United States, and American firms have traditionally been the largest participants in venture deals with the bulk of venture capital being deployed in American companies. However, increasingly, non-US venture investment is growing, and the number and size of non-US venture capitalists have been expanding.

Venture capital has been used as a tool for economic development in a variety of developing regions. In many of these regions, with less developed financial sectors, venture capital plays a role in facilitating access to finance for small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which in most cases would not qualify for receiving bank loans.

In the year of 2008, while VC funding were still majorly dominated by U.S. money ($28.8 billion invested in over 2550 deals in 2008), compared to international fund investments ($13.4 billion invested elsewhere), there has been an average 5% growth in the venture capital deals outside the USA, mainly in China and Europe.[33] Geographical differences can be significant. For instance, in the UK, 4% of British investment goes to venture capital, compared to about 33% in the U.S.[34]

United States

Venture capitalists invested some $29.1 billion in 3,752 deals in the U.S. through the fourth quarter of 2011, according to a report by the National Venture Capital Association. The same numbers for all of 2010 were $23.4 billion in 3,496 deals.[35] A National Venture Capital Association survey found that a majority (69%) of venture capitalists predicted that venture investments in the U.S. would have leveled between $20–29 billion in 2007.[citation needed]

According to a report by Dow Jones VentureSource, venture capital funding fell to $6.4 billion in the USA in the first quarter of 2013, an 11.8% drop from the first quarter of 2012, and a 20.8% decline from 2011. Venture firms have added $4.2 billion into their funds this year, down from $6.3 billion in the first quarter of 2013, but up from $2.6 billion in the fourth quarter of 2012.[36]

Mexico

The Venture Capital industry in Mexico, is a fast growing sector in the country that, with the support of institutions and private funds, is estimated to reach 100 USD billion dollars invested by 2018.[37]

Israel

In Israel, high-tech entrepreneurship and venture capital have flourished well beyond the country's relative size. As it has very little natural resources and, historically has been forced to build its economy on knowledge-based industries, its VC industry has rapidly developed, and nowadays has about 70 active venture capital funds, of which 14 international VCs with Israeli offices, and additional 220 international funds which actively invest in Israel. In addition, as of 2010, Israel led the world in venture capital invested per capita. Israel attracted $170 per person compared to $75 in the USA.[38] About two thirds of the funds invested were from foreign sources, and the rest domestic. In 2013, Wix.com joined 62 other Israeli firms on the Nasdaq.[39] Read more about Venture capital in Israel.

Canada

Canadian technology companies have attracted interest from the global venture capital community partially as a result of generous tax incentive through the Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) investment tax credit program.[citation needed] The basic incentive available to any Canadian corporation performing R&D is a refundable tax credit that is equal to 20% of "qualifying" R&D expenditures (labour, material, R&D contracts, and R&D equipment). An enhanced 35% refundable tax credit of available to certain (i.e. small) Canadian-controlled private corporations (CCPCs). Because the CCPC rules require a minimum of 50% Canadian ownership in the company performing R&D, foreign investors who would like to benefit from the larger 35% tax credit must accept minority position in the company, which might not be desirable. The SR&ED program does not restrict the export of any technology or intellectual property that may have been developed with the benefit of SR&ED tax incentives.

Canada also has a fairly unique form of venture capital generation in its Labour Sponsored Venture Capital Corporations (LSVCC). These funds, also known as Retail Venture Capital or Labour Sponsored Investment Funds (LSIF), are generally sponsored by labor unions and offer tax breaks from government to encourage retail investors to purchase the funds. Generally, these Retail Venture Capital funds only invest in companies where the majority of employees are in Canada. However, innovative structures have been developed to permit LSVCCs to direct in Canadian subsidiaries of corporations incorporated in jurisdictions outside of Canada.

Switzerland

Many Swiss start-ups are university spin-offs, in particular from its federal institutes of technology in Lausanne and Zurich.[40] According to a study by the London School of Economics analysing 130 ETH Zurich spin-offs over 10 years, about 90% of these start-ups survived the first five critical years, resulting in an average annual IRR of more than 43%.[41]

Europe

Europe has a large and growing number of active venture firms. Capital raised in the region in 2005, including buy-out funds, exceeded €60 billion, of which €12.6 billion was specifically allocated to venture investment. The European Venture Capital Association[42] includes a list of active firms and other statistics. In 2006, the top three countries receiving the most venture capital investments were the United Kingdom (515 minority stakes sold for €1.78 billion), France (195 deals worth €875 million), and Germany (207 deals worth €428 million) according to data gathered by Library House.[43]

European venture capital investment in the second quarter of 2007 rose 5% to €1.14 billion from the first quarter. However, due to bigger sized deals in early stage investments, the number of deals was down 20% to 213. The second quarter venture capital investment results were significant in terms of early-round investment, where as much as €600 million (about 42.8% of the total capital) were invested in 126 early round deals (which comprised more than half of the total number of deals).[44]

In 2007, private equity in Italy was €4.2B.

In 2012, in France, according to a study [45] by AFIC (the French Association of VC firms), €6.1B have been invested through 1,548 deals (39% in new companies, 61% in new rounds).

A study published in early 2013 showed that contrary to popular belief, European startups backed by venture capital do not perform worse than US counterparts.[46] European venture backed firms have an equal chance of listing on the stock exchange, and a slightly lower chance of a "trade sale" (acquisition by other company).

In contrast to the US, European media companies and also funds have been pursuing a media for equity business model as a form of venture capital investment.

Leading early-stage venture capital investors in Europe include Mark Tluszcz of Mangrove Capital Partners and Danny Rimer of Index Ventures, both of which were named on Forbes Magazine's Midas List of the world's top dealmakers in technology venture capital in 2007.[47]

Asia

India is fast catching up with the West in the field of venture capital and a number of venture capital funds have a presence in the country (IVCA). In 2006, the total amount of private equity and venture capital in India reached $7.5 billion across 299 deals.[48] In the Indian context, venture capital consists of investing in equity, quasi-equity, or conditional loans in order to promote unlisted, high-risk, or high-tech firms driven by technically or professionally qualified entrepreneurs. It is also defined as "providing seed", "start-up and first-stage financing".[49] It is also seen as financing companies that have demonstrated extraordinary business potential. Venture capital refers to capital investment; equity and debt ;both of which carry indubitable risk. The risk anticipated is very high. The venture capital industry follows the concept of “high risk, high return”, innovative entrepreneurship, knowledge-based ideas and human capital intensive enterprises have taken the front seat as venture capitalists invest in risky finance to encourage innovation.[50]

China is also starting to develop a venture capital industry (CVCA).

Vietnam is experiencing its first foreign venture capitals, including IDG Venture Vietnam ($100 million) and DFJ Vinacapital ($35 million)[51]

Middle East and North Africa

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) venture capital industry is an early stage of development but growing. The MENA Private Equity Association Guide to Venture Capital for entrepreneurs lists VC firms in the region, and other resources available in the MENA VC ecosystem. Diaspora organization TechWadi aims to give MENA companies access to VC investors based in the US.

Southern Africa

The Southern African venture capital industry is developing.

South Africa, with the help of the South African Government and Revenue Service, has realised the necessity to follow the international trend of using tax efficient vehicles to propel economic growth and job creation through venture capital. Section 12 J of the Income Tax Act was updated to include Venture Capital Companies allowing a tax efficient structure similar to VCT's in the UK. Section 12 J provides investors the opportunity to invest in Venture Capital through a tax efficient structure.

Despite the above structure Government needs to adjust regulation around intellectual property, exchange control and other leglislation to ensure that Venture Capital succeeds in South Africa.

Currently, there are not many Venture Capital Funds in operation and it is a small community however funds are available. Funds are difficult to come by and very few firms have managed to get funding despite demonstrating tremendous growth potential.

The majority of the venture capital in Southern Africa is centred around South Africa and Kenya.

Confidential information

Unlike public companies, information regarding an entrepreneur's business is typically confidential and proprietary. As part of the due diligence process, most venture capitalists will require significant detail with respect to a company's business plan. Entrepreneurs must remain vigilant about sharing information with venture capitalists that are investors in their competitors. Most venture capitalists treat information confidentially, but as a matter of business practice, they do not typically enter into Non Disclosure Agreements because of the potential liability issues those agreements entail. Entrepreneurs are typically well-advised to protect truly proprietary intellectual property.

Limited partners of venture capital firms typically have access only to limited amounts of information with respect to the individual portfolio companies in which they are invested and are typically bound by confidentiality provisions in the fund's limited partnership agreement.

In popular culture

In books

- Mark Coggins' novel Vulture Capital (2002) features a venture capitalist protagonist who investigates the disappearance of the chief scientist in a biotech firm in which he has invested. Coggins also worked in the industry and was co-founder of a dot-com startup.[52]

- Drawing on his experience as reporter covering technology for the New York Times, Matt Richtel produced the novel Hooked (2007), in which the actions of the main character's deceased girlfriend, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist, play a key role in the plot.[53]

In comics

- In the Dilbert comic strip, a character named "Vijay, the World's Most Desperate Venture Capitalist" frequently makes appearances, offering bags of cash to anyone with even a hint of potential. In one strip, he offers two small children with good math grades money based on the fact that if they marry and produce an engineer baby he can invest in the infant's first idea. The children respond that they are already looking for mezzanine funding.

- Robert von Goeben and Kathryn Siegler produced a comic strip called The VC between the years 1997-2000 that parodied the industry, often by showing humorous exchanges between venture capitalists and entrepreneurs.[54] Von Goeben was a partner in Redleaf Venture Management when he began writing the strip.[55]

In film

- In Wedding Crashers (2005), Jeremy Grey (Vince Vaughn) and John Beckwith (Owen Wilson) are bachelors who create appearances to play at different weddings of complete strangers, and a large part of the movie follows them posing as venture capitalists from New Hampshire.

- The documentary, Something Ventured (2011), chronicled the recent history of American technology venture capitalists.

In television

- In the TV series Dragons' Den, various startup companies pitch their business plans to a panel of venture capitalists.

- In the ABC reality television show Shark Tank, venture capitalists ("Sharks") invest in entrepreneurs.

See also

- Venture capital financing

- Corporate Venture Capital

- History of private equity and venture capital

- List of venture capital firms

- Adventure capital

- Angel investor

- Crowd funding

- Enterprise Capital Fund a type of Venture Capital fund in the UK

- IPO

- M&A

- National Venture Capital Association

- Private equity

- Private equity secondary market

- Seed funding

- Sweat equity

- Social Venture Capital

- Vulture capitalist

References

- ↑ "Private Company Knowledge Bank".

- ↑ "Venture Impact: The Economic Importance of Venture Backed Companies to the U.S. Economy". Nvca.org. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ Venture Impact (5 ed.). IHS Global Insight. 2009. p. 2. ISBN 0-9785015-7-8.

- ↑ Article: The New Argonauts, Global Search And Local Institution Building. Author : Saxeninan and Sabel

- ↑ Wilson, John. The New Ventures, Inside the High Stakes World of Venture Capital.

- ↑

- Ante, Spencer E. (2008). Creative Capital: Georges Doriot and the Birth of Venture Capital. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 1-4221-0122-3.

- ↑ WGBH Public Broadcasting Service, “Who made America?"-Georges Doriot”

- ↑ The New Kings of Capitalism, Survey on the Private Equity industry The Economist, November 25, 2004

- ↑ "Joseph W. Bartlett, "What Is Venture Capital?"". Vcexperts.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ Kirsner, Scott. "Venture capital's grandfather." The Boston Globe, April 6, 2008.

- ↑ Small Business Administration Investment Division (SBIC)

- ↑ Web site history

- ↑ The Future of Securities Regulation speech by Brian G. Cartwright, General Counsel U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. University of Pennsylvania Law School Institute for Law and Economics Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 24, 2007.

- ↑ In 1971, a series of articles entitled "Silicon Valley USA" were published in the Electronic News, a weekly trade publication, giving rise to the use of the term Silicon Valley.

- ↑ Official website of the National Venture Capital Association, the largest trade association for the venture capital industry.

- ↑ The “prudent man rule” is a fiduciary responsibility of investment managers under ERISA. Under the original application, each investment was expected to adhere to risk standards on its own merits, limiting the ability of investment managers to make any investments deemed potentially risky. Under the revised 1978 interpretation, the concept of portfolio diversification of risk, measuring risk at the aggregate portfolio level rather than the investment level to satisfy fiduciary standards would also be accepted.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 POLLACK, ANDREW. "Venture Capital Loses Its Vigor." New York Times, October 8, 1989.

- ↑ Kurtzman, Joel. " PROSPECTS; Venture Capital." New York Times, March 27, 1988.

- ↑ LUECK, THOMAS J. " High Tech's Glamour fades for some venture capitalists." New York Times, February 6, 1987.

- ↑ Metrick, Andrew. Venture Capital and the Finance of Innovation. John Wiley & Sons, 2007. p.12

- ↑ "MoneyTree Survey". Pwcmoneytree.com. 2006-02-21. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ Dow Jones Private Equity Analyst as referenced in Taub, Stephen. Record Year for Private Equity Fundraising. CFO.com, January 11, 2007.

- ↑ Investment philosophy of VCs.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Cash-strapped entrepreneurs get creative, BBC News.

- ↑ Corporate Finance, 8th Edition. Ross, Westerfield, Jaffe. McGraw-Hill publishing, 2008.]

- ↑ "Bootlaw – Essential law for startups and emerging tech businesses – Up, Up and Away. Should You be Thinking About Venture Debt?". Bootlaw.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "Free database of venture capital funds". Creator.zoho.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "Fund - Butterfly Ventures". Butterfly Ventures. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Private equity industry dictionary. CalPERS Alternative Investment Program

- ↑ Monday, February 15th, 2010 (2010-02-15). "Grow VC launches, aiming to become the Kiva for tech startups". Eu.techcrunch.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "Grow Venture Community". Growvc.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ Austin, Scott (2010-09-09). ""Law Firms Offer Discounts, Play Matchmaker," The Wall Street Journal, Sept. 9, 2010". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "International venture funding rose 5 percent in 2008". VentureBeat. 2009-02-18. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "Mandelson, Peter. "There is no Google, or Amazon, or Microsoft or Apple in the UK, Mandelson tells BVCA." BriskFox Financial News, March 11, 2009". Briskfox.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "Recent Stats & Studies". Nvca.org. 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ Hamilton, Walter (2013-04-18). "Venture-capital funding drops sharply in Southern California". latimes.com. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ↑ "Se afianza en México industria de "venture capital" | EL EMPRESARIO" (in (Spanish)). Elempresario.mx. 2012-08-16. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ↑ What next for the start-up nation?, The Economist, Jan 21st 2012

- ↑ Israel's Wix Reveals IPO Plans, Forbes, Oct 23rd 2013

- ↑ Wagner, Steffen (20 June 2011). "Bright sparks! A portrait of entrepreneurial Switzerland" (PDF). Swiss Business. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ Oskarsson, Ingvi; Schläpfer, Alexander (September 2008). "The performance of Spin-off companies at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich" (PDF). ETH transfer. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ "European Venture Capital Association". Evca.com. 2012-03-01. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ Financial Times Article based on data published by Library House.

- ↑ European Venture Capital, by Sethi, Arjun Sep 2007, accessed December 30, 2007.

- ↑ French Study on 2012 Private Equity Investment in French

- ↑ ^Startup Success in Europe vs. US, Whiteboard, Feb. 2013

- ↑ Technology's Top Dealmakers, Feb. 2007

- ↑ "Venture Capital & Private Equity in India (October 2007)" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "Venture Capital And Private Equity in India".

- ↑ "Venture Capital:An Impetus to Indian Economy".

- ↑ "Let’s Open the 100 Million Dollar Door | IDG Ventures Vietnam – Official Website". IDG Venture Vietnam. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ Liedtke, Michael. "Salon.com, "How Greedy Was My Valley?"". Dir.salon.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ Richtel, Matt. "National Public Radio, "Love, Loss and Digital-Age Deception in Hooke"". Npr.org. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "The VC Comic Strip". Thevc.com. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "San Francisco Chronicle, "Comic Book Pokes Fun at Venture Capitalists"". Sfgate.com. 1999-12-20. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||