Ventricular septal defect

| Ventricular septal defect | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

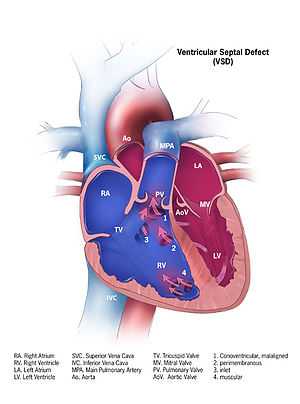

Illustration showing a ventricular septal defect | |

| ICD-10 | Q21.0 |

| ICD-9 | 745.4 |

| DiseasesDB | 13808 |

| MedlinePlus | 001099 |

| eMedicine | med/3517 |

| MeSH | C14.240.400.560.540 |

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a defect in the ventricular septum, the wall dividing the left and right ventricles of the heart.

The ventricular septum consists of an inferior muscular and superior membranous portion and is extensively innervated with conducting cardiomyocytes.

The membranous portion, which is close to the atrioventricular node, is most commonly affected in adults and older children in the United States.[1] It is also the type that will most commonly require surgical intervention, comprising over 80% of cases.[2]

Membranous ventricular septal defects are more common than muscular ventricular septal defects, and are the most common congenital cardiac anomaly. [3]

Diagnosis

A VSD can be detected by cardiac auscultation. Classically, a VSD causes a pathognomonic holo- or pansystolic murmur. Auscultation is generally considered sufficient for detecting a significant VSD. The murmur depends on the abnormal flow of blood from the left ventricle, through the VSD, to the right ventricle. If there is not much difference in pressure between the left and right ventricles, then the flow of blood through the VSD will not be very great and the VSD may be silent. This situation occurs a) in the fetus (when the right and left ventricular pressures are essentially equal), b) for a short time after birth (before the right ventricular pressure has decreased), and c) as a late complication of unrepaired VSD. Confirmation of cardiac auscultation can be obtained by non-invasive cardiac ultrasound (echocardiography). To more accurately measure ventricular pressures, cardiac catheterization, can be performed.

Pathophysiology

During ventricular contraction, or systole, some of the blood from the left ventricle leaks into the right ventricle, passes through the lungs and reenters the left ventricle via the pulmonary veins and left atrium. This has two net effects. First, the circuitous refluxing of blood causes volume overload on the left ventricle. Second, because the left ventricle normally has a much higher systolic pressure (~120 mmHg) than the right ventricle (~20 mmHg), the leakage of blood into the right ventricle therefore elevates right ventricular pressure and volume, causing pulmonary hypertension with its associated symptoms.

In serious cases, the pulmonary arterial pressure can reach levels that equal the systemic pressure. This reverses the left to right shunt, so that blood then flows from the right ventricle into the left ventricle, resulting in cyanosis, as blood is by-passing the lungs for oxygenation.[4]

This effect is more noticeable in patients with larger defects, who may present with breathlessness, poor feeding and failure to thrive in infancy. Patients with smaller defects may be asymptomatic. Four different septal defects exist, with perimembranous most common, outlet, atrioventricular, and muscular less commonly.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Ventricular septal defect is usually symptomless at birth. It usually manifests a few weeks after birth.

Symptoms

VSD is an acyanotic congenital heart defect, aka a Left-to-right shunt, so there are no signs of cyanosis in the early stage. However, uncorrected VSD can increase pulmonary resistance leading to the reversal of the shunt and corresponding cyanosis.

Signs

- Pansystolic (Holosystolic) murmur along lower left sternal border(depending upon the size of the defect) +/- palpable thrill (palpable turbulence of blood flow). Heart sounds are normal. Larger VSDs may cause a parasternal heave, a displaced apex beat (the palpable heartbeat moves laterally over time, as the heart enlarges). An infant with a large VSD will fail to thrive and become sweaty and tachypnoeic (breathe faster) with feeds.[6]

The restrictive VSDs (smaller defects) are associated with a louder murmur and more palpable thrill (grade IV murmur). Larger defects may eventually be associated with pulmonary hypertension due to the increased blood flow. Over time this may lead to an Eisenmenger phenomenon: the original VSD operating with a left-to-right shunt, now becomes a right-to-left shunt because of the increased pressures in the pulmonary vascular bed.

CAUSES: The cause of VSD (ventricular septal defect) includes the incomplete looping of the heart during days 24-28 of development. Faults with NKX2.5 gene can cause this.

Treatment

Most cases do not need treatment and heal at the first years of life. Treatment is either conservative or surgical. Smaller congenital VSDs often close on their own, as the heart grows, and in such cases may be treated conservatively. Some cases may necessitate surgical intervention, i.e. with the following indications:

1. Failure of congestive cardiac failure to respond to medications

2. VSD with pulmonic stenosis

3. Large VSD with pulmonary hypertension

4. VSD with aortic regurgitation

For the surgical procedure, a heart-lung machine is required and a median sternotomy is performed. Percutaneous endovascular procedures are less invasive and can be done on a beating heart, but are only suitable for certain patients. Repair of most VSDs is complicated by the fact that the conducting system of the heart is in the immediate vicinity.

Ventricular septum defect in infants is initially treated medically with cardiac glycosides (e.g., digoxin 10-20 µg/kg per day), loop diuretics (e.g., furosemide 1–3 mg/kg per day) and ACE inhibitors (e.g., captopril 0.5–2 mg/kg per day).

Surgical technique for Repair of Perimembranous VSD

a) Surgical closure of a Perimembranous VSD is performed on cardiopulmonary bypass with ischemic arrest. Patients are usually cooled to 28 degrees. Percutaneous Device closure of these defects is rarely performed in the United States because of the reported incidence of both early and late onset complete heart block after device closure, presumably secondary to device trauma to the AV node.

b) Surgical exposure is achieved through the right atrium. The tricuspid valve septal leaflet is retracted or incised to expose the defect margins.

c) Several patch materials are available, including native pericardium, bovine pericardium, PTFE (Gore-Tex or Impra), or Dacron.

d) Suture techniques include horizontal pledgeted mattress sutures, and running polypropylene suture.

e) Critical attention is necessary to avoid injury to the conduction system located on the left ventricular side of the interventricular septum near the papillary muscle of the conus.

f) Care is taken to avoid injury to the aortic valve with sutures.

g) Once the repair is complete, the heart is extensively deaired by venting blood through the aortic cardioplegia site, and by infusing Carbon Dioxide into the operative field to displace air.

h) Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography is used to confirm secure closure of the VSD, normal function of the aortic and tricuspid valves, good ventricular function, and the elimination of all air from the left side of the heart.

i) The sternum, fascia and skin are closed, with potential placement of a local anesthetic infusion catheter under the fascia, to enhance postoperative pain control.

j) A video of Perimembranous VSD repair, including the operative technique, and the daily postoperative recovery, can be seen here: VSD Repair, Perimembranous Ventricular Septal Defect

Epidemiology and Etiology

VSDs are the most common congenital cardiac anomalies. They are found in 30-60% of all newborns with a congenital heart defect, or about 2-6 per 1000 births. During heart formation, when the heart begins life as a hollow tube, it begins to partition, forming septa. If this does not occur properly it can lead to an opening being left within the ventricular septum. It is debatable whether all those defects are true heart defects, or if some of them are normal phenomena, since most of the trabecular VSDs close spontaneously.[7] Prospective studies give a prevalence of 2-5 per 100 births of trabecular VSDs that closes shortly after birth in 80-90% of the cases.[8][9]

Congenital VSDs are frequently associated with other congenital conditions, such as Down syndrome.[10]

A VSD can also form a few days after a myocardial infarction[11] (heart attack) due to mechanical tearing of the septal wall, before scar tissue forms, when macrophages start remodeling the dead heart tissue.

See also

- Atrial septal defect

- Atrioventricular septal defect

- Cardiac output

- Congenital heart disease

- Heart sounds

- Pulmonary hypertension

Additional images

-

Heart anatomic view of right ventricle and right atrium with example ventricular septal defects

-

Ventricular septal defect

-

Figure A shows the structure and blood flow in the interior of a normal heart. Figure B shows two common locations for a ventricular septal defect. The defect allows oxygen-rich blood from the left ventricle to mix with oxygen-poor blood in the right ventricle.

References

- ↑ Taylor, Michael D. "Muscular Ventricular Septal Defect". eMedicine. Medscape.

- ↑ Waight, David J.; Bacha, Emile A.; Kahana, Madelyn; Cao, Qi-Ling; Heitschmidt, Mary; Hijazi, Ziyad M. (March 2002). "Catheter therapy of Swiss cheese ventricular septal defects using the Amplatzer muscular VSD occluder". Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 55 (3): 355–361. doi:10.1002/ccd.10124. PMID 11870941.

- ↑ Hoffman, JI; Kaplan, S (2002). "The incidence of congenital heart disease". Journal of the American College of Cardiology 39 (12): 1890–900. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01886-7. PMID 12084585.

- ↑ Kumar & Clark 2009

- ↑ Mancini, Mary C. "Ventricular Septal Defect Surgery in the Pediatric Patient". eMedicine. Medscape.

- ↑ Cameron P. et al: Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. p116-117 [Elsevier, 2006]

- ↑ Meberg, A; Otterstad, JE; Frøland, G; Søarland, S; Nitter-Hauge, S (1994). "Increasing incidence of ventricular septal defects caused by improved detection rate". Acta Pædiatrica 83 (6): 653–657. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13102.x.

- ↑ Hiraishi, S; Agata, Y; Nowatari, M; Oguchi, K; Misawa, H; Hirota, H; Fujino, N; Horiguchi, Y; Yashiro, K; Nakae, S (March 1992). "Incidence and natural course of trabecular ventricular septal defect: two-dimensional echocardiography and color Doppler flow imaging study.". The Journal of pediatrics 120 (3): 409–15. PMID 1538287.

- ↑ Roguin, Nathan; Du, Zhong-Dong; Barak, Mila; Nasser, Nadim; Hershkowitz, Sylvia; Milgram, Elliot (15 November 1995). "High prevalence of muscular ventricular septal defect in neonates". Journal of the American College of Cardiology 26 (6): 1545–1548. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(95)00358-4. PMID 7594083.

- ↑ Wells, GL; Barker, SE; Finley, SC; Colvin, EV; Finley, WH (1994). "Congenital heart disease in infants with Down's syndrome". Southern Medical Journal 87 (7): 724–7. doi:10.1097/00007611-199407000-00010. PMID 8023205.

- ↑ Schumacher, Kurt R. "Ventricular septal defect". NIH and US National Library of Medicine. MedlinePlus.

External links

- Pediatric Heart Surgery

- The Congenital Heart Surgery Video Project

- VSD Repair, Perimembranous Ventricular Septal Defect

- VSD Repair Powerpoint™ Presentation

- Ventricular septal defect - Children's Hospital Boston

- Ventricular septal defect - American Heart Association

- Ventricular septal defect - medlineplus.org

- Ventricular Septal Defect information from Seattle Children's Hospital Heart Center

- Animation of ventricular septal defect from AboutKidsHealth.ca

- Perimembranous VSD - emedicine.com

- Supracristal VSD - emedicine.com

- Down's Heart Group Easy to understand diagram and explanation of VSD.

- C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, Congenital Heart Center: Ventricular Septal Defect at umich.edu

- Ventricular Septal Defect Cove Point Foundation

- VSD repair: Perimembranous The Congenital Heart Surgery Video Project

- Ventricular septal defect information for parents.