Velocity of money

The velocity of money (also called velocity of circulation of money and, much earlier, currency) is the frequency at which one unit of currency is used to purchase domestically-produced goods and services within a given time period.[3] In other words, it is the number of times one dollar is spent to buy goods and services per unit of time.[3] If the velocity of money is increasing, then more transactions are occurring between individuals in an economy.[3] Although once thought to be constant,[citation needed] it is now understood that the velocity of money changes over time and is influenced by a variety of factors.[4]

When the period is understood, the velocity may be presented as a pure number; otherwise it should be given as a pure number divided by time.[citation needed]

Illustration

If, for example, in a very small economy, a farmer and a mechanic, with just $50 between them, buy new goods and services from each other in just three transactions over the course of a year

- Farmer spends $50 on tractor repair from mechanic.

- Mechanic buys $40 of corn from farmer.

- Mechanic spends $10 on barn cats from farmer.

then $100 changed hands in the course of a year, even though there is only $50 in this little economy. That $100 level is possible because each dollar was spent on new goods and services an average of twice a year, which is to say that the velocity was  . Note that if the farmer bought a used tractor from the mechanic or made a gift to the mechanic, it would not go into the numerator of velocity because that transaction would not be part of this tiny economy's gross domestic product.

. Note that if the farmer bought a used tractor from the mechanic or made a gift to the mechanic, it would not go into the numerator of velocity because that transaction would not be part of this tiny economy's gross domestic product.

Indirect measurement

In practice, attempts to measure the velocity of money are usually indirect:

where

is the velocity of money for all transactions in a given time frame.

is the velocity of money for all transactions in a given time frame. is the nominal value of aggregate transactions in a given time frame.

is the nominal value of aggregate transactions in a given time frame. is the total amount of money in circulation on average in the economy (see “Money supply” for details).

is the total amount of money in circulation on average in the economy (see “Money supply” for details).

(Given the classical dichotomy,  may be factored into a product

may be factored into a product  of a price level

of a price level  and a 'real' aggregate value of transactions

and a 'real' aggregate value of transactions  .)

.)

Values of  and

and  permit calculation of

permit calculation of  .

.

As applied to an economy, expenditures on final output are of interest; the relation may be written:

where

is the velocity for transactions counting towards national or domestic product.

is the velocity for transactions counting towards national or domestic product. is nominal national or domestic product.

is nominal national or domestic product.

(Analogously with  , given the classical dichotomy,

, given the classical dichotomy,  may be factored into a product

may be factored into a product  .)

.)

-

Velocity of M1 Money Stock in the US 1959–2012

-

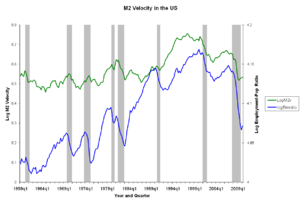

Velocity of M2 Money Stock in the US 1959–2012

-

Velocity of MZM Money Stock in the US 1959–2012

Determination

The determinants and consequent stability of the velocity of money are a subject of controversy across and within schools of economic thought. Those favoring a quantity theory of money have tended to believe that, in the absence of inflationary or deflationary expectations, velocity will be technologically determined and stable, and that such expectations will not generally arise without a signal that overall prices have changed or will change. This view has been discredited by the precipitous fall in velocity in the Japanese "Lost Decade" and the worldwide "Great Recession" and its aftermath of 2008–10. Monetary authorities undertook massive expansion of the money supplies, but instead of lifting nominal GDP as predicted by this theory, velocity fell as nominal GDP was relatively unchanged.[citation needed]

Some people have incorrectly interpreted velocity to mean the time between receipt of income and when it is spent. Note that how much income is spent helps determine GDP, but the time during a pay period at which it is spent is immaterial. There could be a large volume of spending by people who waited a long time between receiving income and spending it. They could store their income in non-money forms, such as stocks and bonds, between receiving income and spending it. So the notion that velocity of money equates to "how fast income is spent" is a fallacy.[citation needed]

The view that velocity of money is constant is criticized by Samuelson thus:

In terms of the quantity theory of money, we may say that the velocity of circulation of money does not remain constant. “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink.” You can force money on the system in exchange for government bonds, its close money substitute; but you can’t make the money circulate against new goods and new jobs.[5]

Criticism

Austrian school of economics

Henry Hazlitt criticized the concept of the velocity of money, citing that the equation used to calculate it ignored the psychological effects that also have a significant role in determining the value of a currency. As an example, he shows that in a period of inflation, that when the money is newly introduced, the price level increases by a smaller proportion than the increase in the supply of money, but that when the money has been in circulation for a while, that the price level has increased by a greater proportion than the supply of money. He states that this is not due to a change in the velocity of money, but rather the discrepancy is due to "fears . . . that the inflation will continue into the future, and that the value of the monetary unit will fall further." Hazlitt offers an alternative to the quantity theory of money and the velocity of money concept that is a necessary consequence. He explains that what changes the value of money is the value that people place on the currency, and that it is not the velocity of money that determines the value of a currency, but rather the sum of individuals' value of the currency that determines the velocity of money.[6]

Ludwig von Mises offered a more philosophical criticism, "The main deficiency of the velocity of circulation concept is that it does not start from the actions of individuals but looks at the problem from the angle of the whole economic system. This concept in itself is a vicious mode of approaching the problem of prices and purchasing power. It is assumed that, other things being equal, prices must change in proportion to the changes occurring in the total supply of money available. This is not true." [7]

References

Notes

- ↑ M2 Definition – Investopedia

- ↑ M2 Money Stock – Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Money Velocity". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ Mishkin, Frederic S. The Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets. Seventh Edition. Addison–Wesley. 2004. p.520.

- ↑ Samuelson, Paul Anthony; Economics (1948), p 354.

- ↑ http://mises.org/daily/2916

- ↑ Ludwig von Mises, Human Action (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1949), and The Theory of Money and Credit (London: Jonathan Cape, Limited, 1934, and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953).

Sources

- Cramer, J.S. “velocity of circulation”, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics(1987), v. 4, pp. 601–02.

- Friedman, Milton; “quantity theory of money”, in The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics (1987), v. 4, pp. 3–20.

External links

- Velocity of money data – from the St. Louis Fed's FRED database