Vector Laplacian

In mathematics and physics, the vector Laplace operator, denoted by  , named after Pierre-Simon Laplace, is a differential operator defined over a vector field. The vector Laplacian is similar to the scalar Laplacian. Whereas the scalar Laplacian applies to scalar field and returns a scalar quantity, the vector Laplacian applies to the vector fields and returns a vector quantity. When computed in rectangular cartesian coordinates, the returned vector field is equal to the vector field of the scalar Laplacian applied on the individual elements.

, named after Pierre-Simon Laplace, is a differential operator defined over a vector field. The vector Laplacian is similar to the scalar Laplacian. Whereas the scalar Laplacian applies to scalar field and returns a scalar quantity, the vector Laplacian applies to the vector fields and returns a vector quantity. When computed in rectangular cartesian coordinates, the returned vector field is equal to the vector field of the scalar Laplacian applied on the individual elements.

Definition

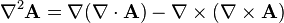

The vector Laplacian of a vector field  is defined as

is defined as

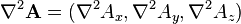

In Cartesian coordinates, this reduces to the much simpler form (This can be seen as a special case of Lagrange's formula, see Vector triple product.)

where  ,

,  , and

, and  are the components of

are the components of  .

.

For expressions of the vector Laplacian in other coordinate systems see Nabla in cylindrical and spherical coordinates.

Generalization

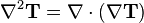

The Laplacian of any tensor field  ("tensor" includes scalar and vector) is defined as the divergence of the gradient of the tensor:

("tensor" includes scalar and vector) is defined as the divergence of the gradient of the tensor:

For the special case where  is a scalar (a tensor of rank zero), the Laplacian takes on the familiar form.

is a scalar (a tensor of rank zero), the Laplacian takes on the familiar form.

If  is a vector (a tensor of first rank), the gradient is a covariant derivative which results in a tensor of second rank, and the divergence of this is again a vector. The formula for the vector Laplacian above may be used to avoid tensor math and may be shown to be equivalent to the divergence of the expression shown below for the gradient of a vector:

is a vector (a tensor of first rank), the gradient is a covariant derivative which results in a tensor of second rank, and the divergence of this is again a vector. The formula for the vector Laplacian above may be used to avoid tensor math and may be shown to be equivalent to the divergence of the expression shown below for the gradient of a vector:

And, in the same manner, a dot product, which evaluates to a vector, of a vector by the gradient of another vector (a tensor of 2nd rank) can be seen as a product of matrices:

This identity is a coordinate dependent result, and is not general.

Use in physics

An example of the usage of the vector Laplacian is the Navier-Stokes equations for a Newtonian incompressible flow:

where the term with the vector Laplacian of the velocity field  represents the viscous stresses in the fluid.

represents the viscous stresses in the fluid.

Another example is the wave equation for the electric field that can be derived from the Maxwell equations in the absence of charges and currents:

The previous equation can also be written as:

where

is the D'Alembertian, used in the Klein–Gordon equation.

References