Vampire squid

| Vampire squid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult vampire squid | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Subclass: | Coleoidea |

| Superorder: | Octopodiformes |

| Order: | Vampyromorphida |

| Suborder: | Vampyromorphina |

| Family: | Vampyroteuthidae |

| Genus: | Vampyroteuthis Chun, 1903 |

| Species: | V. infernalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Vampyroteuthis infernalis Chun, 1903 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

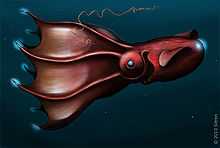

The vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis, lit. "vampire squid of Hell") is a small, deep-sea cephalopod found throughout the temperate and tropical oceans of the world. Unique retractile sensory filaments justify the vampire squid's placement in its own order: Vampyromorphida (formerly Vampyromorpha), which shares similarities with both squid and octopuses. As a phylogenetic relict it is the only known surviving member of its order, first described and originally classified as an octopus in 1903 by German teuthologist Carl Chun, but later assigned to a new order together with several extinct taxa.

Physical description

The vampire squid reaches a maximum total length of around 30 cm (1 ft). Its 15-cm (6-in) gelatinous body varies in colour between velvety jet-black and pale reddish, depending on location and lighting conditions. A webbing of skin connects its eight arms, each lined with rows of fleshy spines or cirri; the inside of this "cloak" is black. Only the distal half (farthest from the body) of the arms have suckers. Its limpid, globular eyes, which appear red or blue, depending on lighting, are proportionately the largest in the animal kingdom at 2.5 cm (1 in) in diameter.[1] The animal's dark colour, cloak-like webbing, and red eyes are what gave the vampire squid its name.[2]

Mature adults have a pair of small fins projecting from the lateral sides of the mantle. These fins serve as the adult's primary means of propulsion: vampire squid "fly" through the water by flapping their fins. Their beak-like jaws are white. Within the webbing are two pouches wherein the tactile velar filaments are concealed. The filaments are analogous to a true squid's tentacles, extending well past the arms; however, they are a different arm pair than the squid's tentacles. Instead, the filaments are the same pair that were lost by the ancestral octopuses.

The vampire squid is almost entirely covered in light-producing organs called photophores. The animal has great control over the organs, capable of producing disorienting flashes of light for fractions of a second to several minutes in duration. The intensity and size of the photophores can also be modulated. Appearing as small, white discs, the photophores are larger and more complex at the tips of the arms and at the base of the two fins, but are absent from the undersides of the caped arms. Two larger, white areas on top of the head were initially believed to also be photophores, but have turned out to be photoreceptors.

The chromatophores (pigment organs) common to most cephalopods are poorly developed in the vampire squid. While this means the animal is not capable of changing its skin colour in the dramatic fashion of shallow-dwelling cephalopods, such ability would not be useful at the lightless depths where it lives.

Habitat and adaptations

The vampire squid is an extreme example of a deep-sea cephalopod, thought to reside at aphotic (lightless) depths from 600 to 900 metres (2,000 to 3,000 ft) or more. Within this region of the world's oceans is a discrete habitat known as the oxygen minimum zone (OMZ). Within the OMZ, oxygen saturation is too low to support aerobic metabolism in most higher organisms. Nonetheless, the vampire squid is able to live and breathe normally in the OMZ at oxygen saturations as low as 3%; an ability that no other cephalopod, and few other animals, possess.

To cope with life in the suffocating depths, vampire squid have developed several radical adaptations. Of all deep-sea cephalopods, their mass-specific metabolic rate is the lowest. Their blue blood's hemocyanin binds and transports oxygen more efficiently than in other cephalopods,[3] aided by gills with especially large surface area. The animals have weak musculature, but maintain agility and buoyancy with little effort because of sophisticated statocysts (balancing organs akin to a human's inner ear)[4] and ammonium-rich gelatinous tissues closely matching the density of the surrounding seawater.

Like many deep-sea cephalopods, vampire squid lack ink sacs. If threatened, instead of ink, a sticky cloud of bioluminescent mucus containing innumerable orbs of blue light is ejected from the arm tips. This luminous barrage, which may last nearly 10 minutes, is presumably meant to daze would-be predators and allow the vampire squid to disappear into the blackness without the need to swim far. The display is made only if the animal is very agitated; regenerating the mucus is metabolically costly.

Development

Few specifics are known regarding the ontogeny of the vampire squid. Their development progresses through three morphologic forms: the very young animals have a single pair of fins, an intermediate form has two pairs, and the mature form again has one. At their earliest and intermediate phases of development, a pair of fins is located near the eyes; as the animal develops, this pair gradually disappears as the other pair develops.[5] As the animals grow and their surface area to volume ratio drops, the fins are resized and repositioned to maximize gait efficiency. Whereas the young propel themselves primarily by jet propulsion, mature adults find flapping their fins to be the most efficient means.[6] This unique ontogeny caused confusion in the past, with the varying forms identified as several species in distinct families.[7]

If hypotheses may be drawn from knowledge of other deep-sea cephalopods, the vampire squid likely reproduces slowly by way of a small number of large eggs. Growth is slow, as nutrients are not abundant at depths frequented by the animals. The vastness of their habitat and its sparse population make procreative encounters a fortuitous event. The female may store a male's hydraulically implanted spermatophore (a tapered, cylindrical satchel of sperm) for long periods before she is ready to fertilize her eggs. Once she does, she may need to brood over them for up to 400 days before they hatch. The female will not eat towards this culmination and dies shortly thereafter.

Hatchlings are about 8 mm in length and are well-developed miniatures of the adults, with some differences. Their arms lack webbing, their eyes are smaller, and their velar filaments are not fully formed. The hatchlings are transparent and survive on a generous internal yolk for an unknown period before they begin to actively feed. The smaller animals frequent much deeper waters, perhaps feeding on marine snow (falling organic detritus).

Behaviour

What behavioural data are known have been gleaned from ephemeral encounters with ROVs; animals are often damaged during capture, and survive for no more than about two months in aquaria. An artificial environment makes reliable observation of non-defensive behaviour difficult.

With their long velar filaments deployed, vampire squid have been observed drifting along in the deep, black ocean currents. If the filaments contact an entity, or if vibrations impinge upon them, the animals investigate with rapid acrobatic movements. They are capable of swimming at speeds equivalent to two body lengths per second, with an acceleration time of five seconds. However, their weak muscles limit stamina considerably.

Unlike their relatives living in more hospitable climes, deep-sea cephalopods cannot afford to expend energy in protracted flight. Given their low metabolic rate and the low density of prey at such depths, vampire squid must use innovative predator avoidance tactics to conserve energy. Their aforementioned bioluminescent "fireworks" are combined with the writhing of glowing arms, erratic movements and escape trajectories, making it difficult for a predator to home in.

In a threat response called "pumpkin" or "pineapple" posture, the vampire squid inverts its caped arms back over the body, presenting an ostensibly larger form covered in fearsome-looking though harmless spines (called cirri).[8] The underside of the cape is heavily pigmented, masking most of the body's photophores. The glowing arm tips are clustered together far above the animal's head, diverting attack away from critical areas. If a predator were to bite off an arm tip, the vampire squid can regenerate it.

Copepods, prawns and cnidarians have all been reported as prey of vampire squid. Recent research has shown they are the only cephalopod not to hunt living prey. They lack feeding tentacles, but in addition to their eight arms, they have two retractile filaments (hypothesized to be homologous to cephalopod tentacles), which they use for the capture of food. They combine the waste with mucus secreted from suckers to form balls of food. They feed on detritus, including remains of gelatinous zooplankton such as salps, larvaceans and medusae, moults of crustaceans, and complete copepods, ostracods, amphipods and isopods.[9][10]

Vampire squid have been found among the stomach contents of large, deepwater fish, such as giant grenadiers,[11] and deep-diving mammals, such as whales and sea lions.

Relationships

The Vampyromorphida are characterized by such apomorphies as the possession of photophores, a peculiar type of uncalcified endoskeleton (the gladius), eight webbed arms, and the two velar filaments. Until fairly recently known only from the modern species and some fossil remains tentatively allocated to this group, a batch of Middle Jurassic (Lower Callovian, c. 165–164 mya) specimens found at La Voulte-sur-Rhône demonstrated vampyromorphid cephalopods clearly were in existence for far longer than had been believed.

These were described as Vampyronassa rhodanica. The supposed vampyromorphids from the Kimmeridgian-Tithonian (156–146 mya) of Solnhofen, Plesioteuthis prisca, Leptoteuthis gigas, and Trachyteuthis hastiformis, cannot be positively assigned to this group; they are large species (from 35 cm in P. prisca to > 1 m in L. gigas) and show features not found in vampyromorphids, being somewhat similar to the true squids, Teuthida.[12]

In popular culture

- A 2009 Rolling Stone article[13] by Matt Taibbi likened investment bank Goldman Sachs to "a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money."[13] Although the metaphor was faulty, since vampire squids do not suck blood or have a "blood funnel", it was later used by other critics of Goldman Sachs, such as the Occupy Wall Street movement.[14]

- Episode 28 of the marine adventure animation The Octonauts was devoted to an encounter with an injured vampire squid.[15]

- In Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Urbervilles, Kim Newman has Professor Moriarty use vampire squid to bring down a scientific rival in disgrace. The rival is induced to believe that they are Martians of the sort described in H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds, leading to his confinement in a madhouse after a disastrous lecture to the Royal Society.

Notes

- ↑ Ellis, Richard. "Introducing Vampyroteuthis infernalis, the vampire squid from Hell". The Cephalopod Page. Dr. James B. Wood. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ↑ Seibel, Brad. "Vampyroteuthis infernalis, Deep-sea Vampire squid". The Cephalopod Page. Dr. James B. Wood. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ↑ Seibel et al. 1999

- ↑ Stephens, P. R.; Young, J. Z. (2009). "The statocyst of Vampyroteuthis infernalis (Mollusca: Cephalopoda)". Journal of Zoology 180 (4): 565–588. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1976.tb04704.x.

- ↑ Pickford 1949

- ↑ (Seibel et al. 1998).

- ↑ (Young 2002).

- ↑ "Vampire Squid Turns "Inside Out"". National Geographic. February 2010. Retrieved June 2011.

- ↑ Hoving, H. J. T.; Robison, B. H. (2012). "Vampire squid: Detritivores in the oxygen minimum zone". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.1357.

- ↑ Vampire squid from hell eats faeces to survive depths

- ↑ Drazen, Jeffrey C; Buckley, Troy W; Hoff, Gerald R (2001). "The feeding habits of slope dwelling macrourid fishes in the eastern North Pacific". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 48 (3): 909–935. doi:10.1016/S0967-0637(00)00058-3.

- ↑ Fischer & Riou 2002

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 By Matt Taibbi (2009-07-09). "The Great American Bubble Machine | Politics News". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2013-05-19.

- ↑ Roose, Kevin (2011-12-13). "The Long Life of the Vampire Squid - NYTimes.com". Dealbook.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- ↑ The Octonauts And The Vampire Squid

References

- Bolstad, Kat (2003). "Deep-Sea Cephalopods: An Introduction and Overview". (Version of 5/6/03, retrieved 2006-DEC-06.)

- Ellis, Richard (1996). "Introducing Vampyroteuthis infernalis, the vampire squid from Hell". In Knopf, Alfred A. The Deep Atlantic: Life, Death, and Exploration in the Abyss. New York. ISBN 0-679-43324-4. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- Fischer, Jean-Claude; Riou, Bernard (2002). "Vampyronassa rhodanica nov. gen. nov sp., vampyromorphe (Cephalopoda, Coleoidea) du Callovien inférieur de la Voulte-sur-Rhône (Ardèche, France)". Annales de Paléontologie 88 (1): 1−17. doi:10.1016/S0753-3969(02)01037-6. (French with English abstract)

- Pickford, Grace E. (1949). "Vampyroteuthis infernalis Chun an archaic dibranchiate cephalopod. II.". External anatomy (Dana Report) (32): 1–132.

- Robison, Bruce H.; Reisenbichler, Kim R.; Hunt, James C.; Haddock, Steven H. D. (2003). "Light Production by the Arm Tips of the Deep-Sea Cephalopod Vampyroteuthis infernalis". Biological Bulletin 205 (2): 102–109.

- Seibel, Brad A. (2001). "Vampyroteuthis infernalis". Archived from the original on 2005-12-24. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- Seibel, Brad A.; Thuesen, Erik V.; Childress, James J. (1998). "Flight of the vampire: ontogenetic gait-transition in Vampyroteuthis infernalis (Cephalopoda: Vampyromorpha)". Journal of Experimental Biology 201 (16): 2413–2424.

- Seibel, Brad A.; Chausson, Fabienne; Lallier, Francois H.; Zal, Franck; Childress, James J. (1999). "Vampire blood: respiratory physiology of the vampire squid (Cephalopoda: Vampyromorpha) in relation to the oxygen minimum layer". Experimental Biology Online 4 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1007/s00898-999-0001-2. (HTML abstract)

- Young, Richard E. (June 2002). "Taxa Associated with the Family Vampyroteuthidae". Retrieved 2006-12-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to vampire squid. |

- "CephBase: Vampire squid". Archived from the original on 2005.

- Tree of Life: Vampyroteuthis infernalis.

- National Geographic video of a vampire squid

- Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI): What the vampire squid really eats.

- Vampire squid

Images

- The vampire squid's photophores and photoreceptors

- Diagram and images of a Vampyroteuthis hatchling

- Photomicrograph of arm tip fluorescence