Valvata piscinalis

| Valvata piscinalis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo of a shell of Valvata piscinalis | |

| |

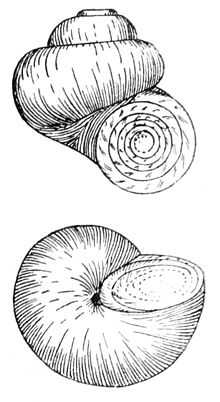

| Drawing: two views of a shell of Valvata piscinalis | |

| Conservation status | |

| NE[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| (unranked): | clade Heterobranchia informal group Lower Heterobranchia |

| Superfamily: | Valvatoidea |

| Family: | Valvatidae |

| Genus: | Valvata |

| Subgenus: | Cincinna Hübner, 1810 |

| Species: | V. piscinalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Valvata piscinalis (O. F. Müller, 1774)[2] | |

Valvata piscinalis, common name the European stream valvata, is a species of minute freshwater snail with gills and an operculum, an aquatic gastropod mollusk in the family Valvatidae, the valve snails. It is also known as Cincinna piscinalis (Müller, 1774).[3]

Subspecies

Subspecies of Valvata piscinalis include:[4]

- Valvata piscinalis piscinalis (O. F. Müller, 1774)

- Valvata piscinalis antiqua (Morris, 1838)

- Valvata piscinalis geyeri (Menzel, 1904) - The name geyeri is in honor of German zoologist David Geyer (1855–1932).

- Valvata piscinalis discors (Westerlund, 1886)

- Valvata piscinalis alpestris (Küster, 1853)

Shell description

Valvata piscinalis has a somewhat pinched aperture and an attenuate spire.[5] The spire height tends to increases in more eutrophic conditions.[5][6] Shells of this species often exhibit 4–5 whorls[5] and are white to beige with more orange to red pigmentation apically.[6] The operculum shows spiral markings of around 10 turns, originating almost centrally.[6]

The European valve snail can be confused with Valvata sincera, a native species in the Great Lakes; however, the United States species has a more spherical aperture, a wider umbilicus, a conical spire and more widely spaced and rough growth lines on the shell in comparison with the introduced species.[5] In the Great Lakes, mature adult European valve snails are 5 mm high and 3–5 mm wide.[5] In Europe, this snail has been found up to 7 mm high and 6.5 mm wide, but is usually smaller.[6]

Dimensions of the shell are:[4]

- Valvata piscinalis piscinalis - The width of the shell is 4–5 mm. The height of the shell is 3-4.5 mm.

- Valvata piscinalis antiqua - width: 4.5 mm. height: 6 mm.

- Valvata piscinalis geyeri - width: 2.5 mm. height: 3 mm.

- Valvata piscinalis discors - width: 3 mm. height: 3 mm.

- Valvata piscinalis alpestris - width: 6.3 mm. height: 5.5 mm.

Anatomy

The animals are yellow colored, spotted grey and white, with darker pigmentation on the snout, mantle and base of the penis.[6] Blue eyes are at the base of long tentacles. Valvatids all exhibit an external bipectinate ctenidium (respiratory organ) which is visible as the animal moves around.[6]

Distribution

The distribution of Valvata piscinalis is Palearctic.[4][7]

Although this species is widely distributed in some areas in North America as an introduced species, Valvata piscinalis has declined in some parts of its native distribution, and in some areas it is endangered.

Indigenous distribution

This species occurs in the British Isles and throughout Europe, to Asia Minor and all the way to Tibet.[8]

The European valve snail is native to Europe, the Caucasus, western Siberia and Central Asia and is common in many freshwater environments therein.[5] It is entirely absent from Iceland.[6]

Europe:

- Austria - endangered (3, gefährdet)[4]

- Croatia[9]

- Czech Republic - near threatened (NT)[7]

- Slovakia

- Poland

- Germany - (Arten der Vorwarnliste): critically endangered (2, stark gefährdet) in Saxony and in Thuringia, endangered (3, gefährdet) in Berlin, (4R, rückläufig) in Bavaria, species with limited distribution in Brandenburg, (Arten der Vorwarnliste) in Hesse and in North Rhine-Westphalia. In other federal states of Germany the species is common.[10]

- Netherlands[11]

- the British Isles: Great Britain and Ireland

- Sweden - not in red list[12]

Asia:

Nonindigenous distribution

Valvata piscinalis is an introduced species in the United States. The European valve snail was originally introduced to Lake Ontario at the mouth of the Genesee River in 1897. In forty years it dispersed to Lake Erie and subsequently it expanded its range to the Saint Lawrence River, the Hudson River, Champlain Lake and Cayuga Lake. Valvata piscinalis was recorded in the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century in Superior Bay in Lake Superior (Minnesota), Lake Michigan (Wisconsin) and Oneida Lake in the Lake Ontario watershed (New York State).[5]

Ecology

Habitat

This small snail is found in freshwater streams, rivers, and lakes, preferring running water and tolerating water with low calcium levels.[8]

In its native range, this species’ presence has been associated with oligotrophic nearshore zones,[5] clear-water habitats more than turbid water, sparsely vegetated lakes or sites dominated by Chara spp. and Potamogeton spp.,[14][15] littoral habitats with high siltation rates,[16] lentic and stagnant waters or slow streams,[17] fine substrates (mud, silt and sand) – especially during hibernation, and aquatic macrophytes – for laying its egg masses.[5]

The snail appears to be somewhat resistant to declines in macrophyte cover, because populations have been recorded to survive in ponds after vegetation cover almost completely disappeared.[18] This species is found at depths anywhere from 0.5 m to 23 m in the Great Lakes.[5] In Europe, it usually is found in depths of up to 10 m.[6]

Valvata piscinalis tolerates varying calcium concentrations, and generally does not require very high temperatures to survive.[5][6] Individuals can overwinter in mud, often experiencing growth during this cold period,[6][19] although some populations may experience mortality in frozen littoral zones.[20] This species can tolerate salinities up to 0.2%[6] and is distributed in northern parts of the Curonian Lagoon, where it experiences periodic intrusions of saline water for a few hours or days at a time.[21][22]

Feeding habits

The species is an efficient feeder, grazing on epiphytic algae and detritus, and in more eutrophic environments is capable of filter feeding on suspended organic matter and algae.[5] Valvata piscinalis can also rasp off pieces of aquatic vegetation.[6]

Life cycle

Valvata piscinalis is known for its rapid growth and high fecundity. It reproduces as a hermaphrodite, one individual acting as the male and the other as the female, and has no free larval stage.[5][6] It may spawn 2 or 3 times in a year, laying up to 150 eggs at a time[5] which are deposited on vegetation. Hatching normally occurs in 15–30 days.[6] Individuals breed around the age of 1 and usually die at 13–21 months.[5] In Europe, breeding occurs from April to September, occurring later at more northerly latitudes.[6]

Parasites

Valvata piscinalis is a common first intermediate host for the parasitic trematode Echinoparyphium recurvatum[23] and has also been shown to act as the first and second intermediate hosts to Echinoparyphium mordwilokoi in native environments in Europe.[24][25][26]

- As second intermediate host for Cyanthocotyle bushiensis[27]

- As intermediate host for Syngamus trachea[28]

Other interspecific relationships

This snail has chemosensory perception, which allows it to detect nearby leeches, and distinguish molluscivores from non-molluscivores, and thus it can close its operculum to avoid predation.[29]

References

- ↑ 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Cited 10 November 2007.

- ↑ Müller, O. F. 1774. Vermivm terrestrium et fluviatilium, seu animalium infusoriorum, helminthicorum, et testaceorum, non marinorum, succincta historia. Volumen alterum. - pp. I-XXVI [= 1-36], 1-214, [1-10]. Havniæ & Lipsiæ. (Heineck & Faber).

- ↑ (Russian) Anistratenko O., Degtyarenko E., Anistratenko V. (2010). "Сравнительная морфология раковины и радулы брюхоногих моллюсков семейства Valvatidae из Северного Причерноморья. [Shell and radula comparative morphology of the Gastropod Molluscs family Valvatidae from the North Black Sea coast]". Ruthenica 20(2): 91-101. PDF

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Glöer, P. 2002 Die Süßwassergastropoden Nord- und Mitteleuropas. Die Tierwelt Deutschlands, ConchBooks, Hackenheim, 326 pp., ISBN 3-925919-60-0, page 190-194.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 Grigorovich, I. A., E. L. Mills, C. B. Richards, D. Breneman and J. J. H. Ciborowski. 2005. European valve snail Valvata piscinalis (Muller) in the Laurentian Great Lakes basin. Journal of Great Lakes Research 31(2):135-143.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 Fretter, V. and A. Graham. 1978. The prosobranch mollusks of Britain and Denmark; Part 3: Neritacea, Viviparacea, Valvatacea, terrestrial and fresh water Littorinacea and Rissoacea. Journal of Molluscan Studies Supplement 5:101-150.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Beran L. 2002: Vodní měkkýši České republiky - rozšíření a jeho změny, stanoviště, šíření, ohrožení a ochrana, červený seznam. [Aquatic molluscs of the Czech Republic -- distribution and its changes, habitats, dispersal, threat and protection, Red List]. Sborník přírodovědného klubu v Uherském Hradišti, Supplementum 10, 258 pp., page 50-51 and 229.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Janus, Horst, 1965. ‘’The young specialist looks at land and freshwater molluscs’’, Burke, London.

- ↑ Beran L. (2009). "The first record of Anisus vorticulus (Troschel, 1834) (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) in Croatia?". Malacologica Bohemoslovaca 8: 70. PDF.

- ↑ Glöer P. & Meier-Brook C. (2003) Süsswassermollusken. DJN, pp. 134, page 108, ISBN 3-923376-02-2. (in German)

- ↑ Valvata piscinalis — Anemoon, accessed 20 October 2008

- ↑ von Proschwitz, T. 2001. Svenska sötvattensmollusker (snäckor och musslor) - en uppdaterad checklista med vetenskapliga och svenska namn. (on-line) Naturhistoriska riksmuseet. http://www.nrm.se/ev/dok/sotvmollhtml.se, February 23, 2001 http://www.nrm.se/download/18.4e32c81078a8d9249800016704/sotvmoll.pdf (in Swedish)

- ↑ (file created 29 July 2010) FRESH WATER MOLLUSCAN SPECIES IN INDIA. 11 pp. accessed 31 July 2010.

- ↑ Van den Berg, M. S., H. Coops, R. Noordhuis, J. Van Schie and J. Simons. 1995. Macroinvertebrate communities in relation to submerged vegetations in two Chara-dominated lakes. Hydrobiologia 342-343:143-150.

- ↑ Van den Berg, M. S., R. Doef, F. Zant and H. Coops. 1997. Charophytes: clear water and macroinvertebrates in the lakes Veluwemeer and Wolderwijd. Levende Natuur. 98(1):14-19.

- ↑ Smith, H., J.A. Van den Velden and A. Klinik. 1994. Macrozoobenthic assemblages in littoral sediments in the enclosed Rhine-Meuse delta. Netherlands Journal of Aquatic Ecology 28(2):199-212.

- ↑ Frank, C. 1987. A contribution to the knowledge of Hungarian Mollusca part III. Berichte des Naturwissenschaftlich-Medizinischen Vereins in Innsbruck 74:113-124.

- ↑ Lodge, D. M. and P. Kelly. 1985. Habitat disturbance and the stability of freshwater gastropod populations. Oecologia 68(1):111-117.

- ↑ Chernogorenko, M. I. 1980. Seasonal dynamics of mollusk infestation by larvae and parthenitae in the Dnieper River Ukrainian-SSR USSR. Vestnik Zoologii 5:53-56.

- ↑ Olson, T. I. 1984. Winter sites and cold-hardiness of two gastropod species in a boreal river. Polar Biology 3(4):227-230.

- ↑ Bubinas, A. and G. Vaitonis. 2005. The structure and seasonal dynamics of zoobenthic communities in the northern and central parts of the Curonian lagoon. Acta Zoologica Lituanica 15(4):297-304.

- ↑ Olenin, S. and D. Daunys. 2005. Invaders in suspension-feeding systems: variations along the regional environmental gradient and similarities between large basins. Pp. 221-237 in R. Dame and S. Olenin, eds. The Comparative Roles of Suspension-Feeders in Ecosystems. NATO Science Series. Earth and Environmental Series 47.

- ↑ Echinoparyphium recurvatum, Parasite species summary page, accessed 20 October 2008.

- ↑ Evans, N. A., P. J. Whitfield and A. P. Dobson. 1981. Parasite utilization of a host community: the distribution and occurrence of metacercarial cysts of Echinoparyphium recurvatum (Digenea: Echinostomatidae) in seven species of mullusc at Harting Pond, Sussex. Parasitology 83(1):1-12.

- ↑ Grabda-Kazubska, B. and V. Kiseliene. 1991. The life cycle of Echinoparyphium mordwilkoi Skrjabin, 1914 (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae). Acta Parasitologica Polonica 36(4):167-173.

- ↑ McCarthy, A. M. 1990. Speciation of echinostomes; evidence for the existence of two sympatric sibling species in the complex Echinoparyphium recurvatum Von Linstow, 1873 (Digenea: Echinostomatidae). Parasitology 101(1):35-42.

- ↑ Cyanthocotyle bushiensis, Parasite species summary page, accesseed 20 October 2008.

- ↑ Syngamus trachea, Parasite species summary page, accesseed 20 October 2008.

- ↑ Kelly, P.M. and J. S. Cory. 1987. Operculum closing as a defense against predatory leeches in four British freshwater prosobranch snails. Hydrobiologia 144(2):121-124.

This article incorporates public domain text from:

- Rebekah M. Kipp & Amy Benson. 2008. Valvata piscinalis. USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL. <http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.asp?speciesID=1043> Revision Date: 2/25/2007

Further reading

- Mills, E. L., J. H. Leach, J. T. Carlton and C. L. Secor. 1993. Exotic species in the Great Lakes: a history of biotic crises and anthropogenic introductions. Journal of Great Lakes Research 19(1):1-54.