Vachellia farnesiana

| Vachellia farnesiana | |

|---|---|

| |

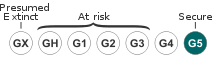

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Genus: | Vachellia |

| Species: | V. farnesiana |

| Binomial name | |

| Vachellia farnesiana (L.) Willd. | |

| varieties | |

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Vachellia farnesiana, also known as Acacia farnesiana, and previously Mimosa farnesiana, commonly known as needle bush, is so named because of the numerous thorns distributed along its branches. The native range of V. farnesiana is uncertain. While the point of origin is Mexico and Central America, the species has a pantropical distribution incorporating northern Australia and southern Asia. It remains unclear whether the extra-American distribution is primarily natural or anthropogenic.[1] It is deciduous over part of its range,[2] but evergreen in most locales.[3] The species grows to a height of up to 8 m (26 ft)[4] and has a lifespan of about 25–50 years.[5]

The plant has been recently spread to many new locations as a result of human activity and it is considered a serious weed in Fiji, where locals call it Ellington's curse. It thrives in dry, saline, or sodic soils. It is also a serious pest plant in parts of Australia, including north-west New South Wales, where it now infests thousands of acres of grazing country.[6]

The taxon name farnesiana is specially named after Odoardo Farnese (1573–1626) of the notable Italian Farnese family which, after 1550, under the patronage of cardinal Alessandro Farnese, maintained some of the first private European botanical gardens in Rome, in the 16th and 17th centuries. Under stewardship of these Farnese Gardens this acacia was imported to Italy.[7] The plant itself was brought to the Farnese Gardens from the Caribbean and Central America, where it originates.[8][9] Analysis of essences of the floral extract from this plant, long used in perfumery, resulted in the name for the sesquiterpene biosynthetic chemical farnesol, found as a basic sterol precursor in plants, and cholesterol precursor in animals.[8]

Some of the reported uses of the plant

Bark

The bark is used for its tannin content.[4] Highly tannic barks are common in general to acacias, extracts of many being are used in medicine for this reason. (See cutch).

Food

The leaves are used as a tamarind flavoring for chutneys and the pods are roasted to be used in sweet and sour dishes.[10]

Flowers

The flowers are processed through distillation to produce a perfume called Cassie. It is widely used in the perfume industry in Europe. Flowers of the plant provide the perfume essence from which the biologically important sesquiterpenoid farnesol is named.

Scented ointments from Cassie are made in India.[4]

Foliage

The foliage is a significant source of forage in much of its range, with a protein content around 18%.

Seed pods

The concentration of tannin in the seed pods is about 23%.

Seeds

The seeds of V. farnesiana are not toxic to humans[11] and are a valuable food source for people throughout the plant's range. The ripe seeds are put through a press to make oil for cooking.[12] Nonetheless, an anecdotal report has been made that in Brazil some people use the seeds of V. farnesiana to eliminate rabid dogs.[4] This is attributed to an unnamed toxic alkaloid.

Forage

The tree makes good forage for bees.[13]

Dyes and inks

A black pigment is extracted from the bark and fruit.[13]

Traditional medicine

The bark and the flowers are the parts of the tree most used in traditional medicine.[12] V. farnesiana has been used in Colombia to treat malaria, and the extract from the tree bark and leaves has shown some efficacy against the malarial pathogen Plasmodium falciparum in animal models .[14] Indigenous Australians have used the roots and bark of the tree to treat diarrhea and diseases of the skin.[13] The tree's leaves can also be rubbed on the skin to treat skin diseases.[15][medical citation needed]

Common names

Farnese wattle, dead finish, mimosa wattle, mimosa bush, prickly mimosa bush, prickly Moses, needle bush, north-west curara, sheep's briar, sponge wattle, sweet acacia, thorny acacia, thorny feather wattle, wild briar, huisache, cassie, cascalotte, cassic, mealy wattle, popinac, sweet briar, Texas huisache, aroma, (Bahamas) cashia, (Bahamas, USA) opoponax, sashaw, (Belize) suntich, (Jamaica) sassie-flower, iron wood, cassie flower, honey-ball, casha tree, casha, (Virgin Islands) cassia, (Fiji) Ellington's curse, cushuh, (St. Maarten), huizache (Mexico).

References

- ↑ Clarke, H.D., Seigler, D.S., Ebinger, J.E. 1989; 'Acacia farnesiana (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae) and Related Species from Mexico, the Southwestern U.S., and the Caribbean' Systematic Botany 14 549-564

- ↑ PDF Ursula K. Schuch and Margaret Norem, Growth of Legume Tree Species Growing in the Southwestern United States, University of Arizona.

- ↑ "Discover Life - Fabaceae: Acacia farnesiana (L. ) Willd. - Cassie Flower, Vachellia farnesiana, Poponax farnesiana, Mimosa farnesiana, Ellington Curse, Klu, Sweet Acacia, Mimosa Bush, Huisache". Pick5.pick.uga.edu. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Purdue University". Hort.purdue.edu. 1997-12-16. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑ "Acacia salicina Lindley". Worldwidewattle.com. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- ↑ "Mimosa bush - briar bush". Northwestweeds.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ↑ "Etymology of farnesol, accessed August 27, 2009". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "HENRY TRIMBLE AND F. D. MACFARLAND., AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHARMACY, Volume 57, #3, March, 1885" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑ "Location of the Farnese family gardens, now known only as a remnant". Gardenvisit.com. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑ "One-garden" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Herbal remedy". Mhra.gov.uk. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Bottlebrush Press". Bottlebrush Press. 2003-05-20. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑ Garavito, G.; Rincón, J.; Arteaga, L.; Hata, Y.; Bourdy, G.; Gimenez, A.; Pinzón, R.; Deharo, E. (2006). "Antimalarial activity of some Colombian medicinal plants". Journal of Ethnopharmacology 107 (3): 460–462. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.033. PMID 16713157.

- ↑ "Philippine Herbs Used in Small Animal Practice". Stuartxchange.org. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

External links

- Dr. Duke's Database

- Interactive Distribution Map of Vachellia farnesiana

- Acacia farnesiana Israel Native Plants

- Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. Medicinal Plant Images Database (School of Chinese Medicine, Hong Kong Baptist University) (traditional Chinese) (English)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vachellia farnesiana. |