Vachellia drepanolobium

| Vachellia drepanolobium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Genus: | Vachellia |

| Species: | V. drepanolobium |

| Binomial name | |

| Vachellia drepanolobium (Harms ex Sjöstedt) P.J.H.Hurter[1] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

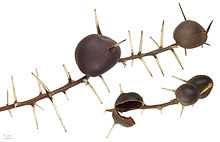

Vachellia drepanolobium, commonly known as Whistling Thorn (family Fabaceae), is a swollen-thorn vachellia native to East Africa.[2] The whistling thorn grows up to 6 meters tall. It produces a pair of straight thorns at each node, some of which have large bulbous bases. These swollen thorns are naturally hollow and occupied by any one of several symbiotic ant species. The common name of the plant is derived from the observation that when wind blows over bulbous thorns in which ants have made entry/exit holes, they create a whistling noise.[3]

Whistling thorn is the dominant tree in some areas of upland East Africa, sometimes forming a nearly monoculture woodland, especially on "black cotton" soils of impeded drainage with high clay content.[4][5] It is browsed upon by giraffes and other large herbivores. It is apparently fire-adapted, coppicing readily after "top kill" by fire.[6]

Whistling thorn is used as fencing, tool handles, and other implements. The wood of the Whistling Thorn, although usually small in diameter, is hard and resistant to termites.[2][7] The branches can also be used for kindling, and its gum is sometimes collected and used as glue. The ability to coppice after cutting make it a possibly sustainable source for fuel wood and charcoal.[8] Conversely, Whistling Thorn also has been considered a weed of rangelands, and a bush encroachment species.[9][10]

Symbiosis with ants

Like other vachellias, Whistling Thorns have leaves that contain tannins, which are thought to serve a deterrents to herbivory. Like all vachellias, they are defended by spines.[11] In addition, Whistling thorn vachellias are myrmecophytes that have formed a mutualistic relationship with some species of ants. In exchange for shelter in the bulbous thorns (domatia) and nectar secretions, these ants appear to defend the tree against herbivores, such as elephants and giraffes,[12][13] as well as herbivorous insects.

At one site in Kenya, four ant species compete for exclusive possession of individual whistling thorn trees: Crematogaster mimosae, C. sjostedti, C. nigriceps, and Tetraponera penzigi.[4][5] Ants vary in their level of mutualism with whistling thorn trees. The most common ant symbiote (~ 50% of trees), C. mimosae, has the strongest mutualistic relationship, aggressively defending trees from herbivores while relying heavily on swollen-thorns for shelter and feeding off of nectar produced by glands near the base of leaves. (see also Crematogaster peringueyi)

Because the ants compete for exclusive usage of a given tree, some species employ tactics to reduce the chance of a hostile ant invasion. Crematogaster nigriceps ants trim the buds of trees to reduce lateral growth in trees, thereby reducing chances of contact with a neighboring tree. Tetraponera penzigi, the only species which does not utilize the nectar produced by the trees, instead destroys the nectar glands in order to make a tree less appealing to other species.

The symbiotic relationship between the trees and the ants appears to be maintained by the effects of browsing by large herbivores. At a site in Kenya, when large herbivores were experimentally excluded, trees reduced the number of nectar glands and swollen thorns they provided to ants. In response, the usually dominant C. mimosae increased their tending of parasitic sap-sucking insects as a replacement food source. In addition, the number of C. mimosae-occupied trees declined while twice as many become occupied by C. sjostedti, a much less aggressive defender of trees. Because C. sjostedti benefits from the holes created by boring beetle larvae, this species facilitates parasitism of trees by the beetles. As a result, the mutualistic relationship between whistling thorn trees and resident ants breaks down in the absence of large herbivores, and trees become paradoxically less healthy as a result.[5]

References

- ↑ Kyalangalilwa B, Boatwright JS, Daru BH, Maurin O, van der Bank M. (2013). "Phylogenetic position and revised classification of Acacia s.l. (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae) in Africa, including new combinations in Vachellia and Senegalia.". Bot J Linn Soc 172 (4): 500–523. doi:10.1111/boj.12047.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Vachellia drepanolobium (as Acacia drepanolobium) (Whistling Thorn)". ZipcodeZoo.com. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ↑ "Whistling Thorn". Archived from the original on 26 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Young, T.P.; Cynthia H. Stubblefield, Lynne A. Isbell (December 1996). "Ants on swollen-thorn acacias: species coexistence in a simple system". Oecologia 109 (1): 98–107. doi:10.1007/s004420050063. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Palmer, Todd; Maureen L. Stanton, Truman P. Young, Jacob R. Goheen, Robert M. Pringle, Richard Karban (January 2008). "Breakdown of an Ant-Plant Mutualism Follows the Loss of Large Herbivores from an African Savanna". Science 319 (5860): 192–195. doi:10.1126/science.1151579. PMID 18187652. Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ Okello, Bell; Truman P. Young, Corinna Riginos, Dan Kelly, Tim O'Connor (2008). "Short-term survival and long-term mortality of Acacia drepanolobium after a controlled burn". African Journal of Ecology 46 (3): 395–401. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2007.00872.x.

- ↑ "The Whistling Thorn". Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ↑ Okello, B.D., O’Connor, T.G. & Young, T.P. (2001). "Growth, biomass estimates, and charcoal production of Acacia drepanolobium in Laikipia, Kenya". For. Ecol. & Manag. 142: 143–153. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00346-7.

- ↑ Pratt, D.J. & Gwynne, M.D. (1977). Rangeland Management and Ecology in East Africa. Hodder & Stoughton, London. ISBN 0-88275-525-0.

- ↑ Dall, G., Maass, B.L. & Isselstein, J. (2006). "Encroachment of woody plants and its impact on pastoral livestock production in the Borana lowlands, southern Oromia, Ethiopia". Afr. J. Ecol. 44 (2): 237–246. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00638.x.

- ↑ Ward, D. & T.P. Young (2002). "Effects of large mammalian herbivores and ant symbionts on condensed tannins of Acacia drepanolobium in Kenya". Journal of Chemical Ecology 28 (5): 921–937. doi:10.1023/A:1015249431942. PMID 12049231.

- ↑ Madden, D. and T.P. Young. Symbiotic ants as an alternative defense against giraffe herbivory in spinescent Acacia drepanolobium. Oecologia 91:235-238.

- ↑ Jacob R. Goheen, and Todd M. Palmer,"Defensive Plant-Ants Stabilize Megaherbivore-Driven Landscape Change in an African Savanna", Current Biology,Available online 2 September 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vachellia drepanolobium. |