Urban ecology

Urban ecology is the scientific study of the relation of living organisms with each other and their surroundings in the context of an urban environment. The urban environment refers to environments dominated by high-density residential and commercial buildings, paved surfaces, and other urban-related factors that create a unique landscape dissimilar to most previously studied environments in the field of ecology.[1]

Urban ecology is a recent field of study compared to ecology as a whole. The methods and studies of urban ecology are similar to and comprise a subset of ecology. The study of urban ecology carries increasing importance because, within the next forty years, two-thirds of the world’s population will be living in expanding urban centers.[2] The ecological processes in the urban environment are comparable to those outside the urban context. However, the types of urban habitats and the species that inhabit them are poorly documented. Often, explanations for phenomena examined in the urban setting as well as predicting changes because of urbanization are the center for scientific research.[1]

History of urban ecology

Ecology has historically focused on 'pristine' natural environments, but by the 1970s many ecologists began to turn their interest towards ecological interactions taking place in, and caused by urban environments. Jean-Marie Pelt's 1977 book,[3]The Re-Naturalized Human, Brian Davis’ 1978 publication,[4] Urbanization and the diversity of insects, as well as, Sukopp et al.’s 1979 article,[5] The soil, flora and vegetation of Berlin’s wastelands are some of the first publications to recognize the importance of urban ecology as a separate and distinct form of ecology the same way one might see landscape ecology as different from population ecology. Forman and Godron’s 1986 book,[6] Landscape Ecology, first distinguished urban settings and landscapes from other landscapes by dividing all landscapes into five broad types. These types were divided by the intensity of human influence ranging from pristine natural environments to urban centers.

Urban ecology is recognized as a diverse and complex concept which differs in application between North America and Europe. The European concept of urban ecology examines the biota of urban areas while to the North American concept which has traditionally examined the social sciences of the urban landscape.[7] as well as the ecosystem fluxes and processes.[8]

Methods of studying urban ecology

Since urban ecology is a subfield of ecology, many of the techniques are similar to that of ecology. Ecological study techniques have been developed over centuries, but many of the techniques use for urban ecology are more recently developed. Methods used for studying urban ecology involve chemical and biochemical techniques, temperature recording, heat mapping remote sensing, and long-term ecological research sites.

Chemical and biochemical techniques

Chemical techniques may be used to determine pollutant concentrations and their effects. Tests can be as simple as dipping a manufactured test strip, as in the case of pH testing, or be more complex, as in the case of examining the spatial and temporal variation of heavy metal contamination due to industrial runoff.[9] In that particular study, livers of birds from many regions of the North Sea were ground up and mercury was extracted. Additionally, mercury bound in feathers was extracted from both live birds and from museum specimens to test for mercury levels across many decades. Through these two different measurements, researchers were able to make a complex picture of the spread of mercury due to industrial runoff both spatially and temporally.

Other chemical techniques include tests for nitrates, phosphates, sulfates, etc. which are commonly associated with urban pollutants such as fertilizer and industrial byproducts. These biochemical fluxes are studied in the atmosphere (e.g. greenhouse gasses), aquatic ecosystems and soil vegetation.[10] Broad reaching effects of these biochemical fluxes can be seen in various aspects of both the urban and surrounding rural ecosystems.

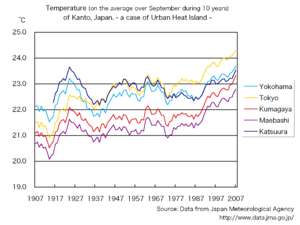

Temperature data and heat mapping

Temperature data can be used for various kinds of studies. An important aspect of temperature data is the ability to correlate temperature with various factors that may be affecting or occurring in the environment. Oftentimes, temperature data is collected long-term by the Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR), and made available to the scientific community through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).[11] Data can be overlaid with maps of terrain, urban features, and other spatial areas to create heat maps. These heat maps can be used to view trends and distribution over time and space.[11][12]

Remote sensing

Remote sensing is the technique in which data is collected from distant locations through the use of satellite imaging, radar, and aerial photographs. In urban ecology, remote sensing is used to collect data about terrain, weather patterns, light, and vegetation. One application of remote sensing for urban ecology is to detect the productivity of an area by measuring the photosynthetic wavelengths of emitted light.[13] Satellite images can also be used to detect differences in temperature and landscape diversity to detect the effects of urbanization.[12]

LTERs and long-term data sets

Long-term ecological research (LTER) sites are research sites funded by the government that have collected reliable long-term data over an extended period of time in order to identify long-term climatic or ecological trends. These sites provide long-term temporal and spatial data such as average temperature, rainfall and other ecological processes. The main purpose of LTERs for urban ecologists is the collection of vast amounts of data over long periods of time. These long-term data sets can then be analyzed to find trends relating to the effects of the urban environment on various ecological processes, such as species diversity and abundance over time.[13] Another example is the examination of temperature trends that are accompanied with the growth of urban centers.[14]

Urban effects on the environment

Humans are the driving force behind urban ecology and influence the environment in a variety of ways, such as modifying land surfaces and waterways, introducing foreign species, and altering biogeochemical cycles. Some of these effects are more apparent, such as the reversal of the Chicago River to accommodate the growing pollution levels and trade on the river.[15] Other effects can be more gradual such as the change in global climate due to urbanization.[16]

Modification of land and waterways

Along with manipulation of land to suit human needs, natural water resources such as rivers and streams are also modified in urban establishments. Modification can come in the form of dams, artificial canals, and even the reversal of rivers. Reversing the flow of the Chicago River is a major example of urban environmental modification.[15] Urban areas in natural desert settings often bring in water from far areas to maintain the human population and will likely have effects on the local desert climate.[13] Modification of aquatic systems in urban areas also results in decreased stream diversity and increased pollution.[18]

Trade, shipping and the spread of invasive species

Both local shipping and long-distance trade are required to meet the resource demands important in maintaining urban areas. Carbon dioxide emissions from the transport of goods also contribute to accumulating greenhouse gases and nutrient deposits in the soil and air of urban environments.[10] In addition, shipping facilitates the unintentional spread of living organisms, and introduces them to environments that they would not naturally inhabit. Introduced or alien species are populations of organisms living in a range in which they did not naturally evolve due to intentional or inadvertent human activity. Increased transportation between urban centers furthers the incidental movement of animal and plant species. Alien species often have no natural predators and pose a substantial threat to the dynamics of existing ecological populations in the new environment where they are introduced. Such invasive species are numerous and include house sparrows, ring-necked pheasants, European starlings, brown rats, Asian carp, American bullfrogs, emerald ash borer, Kudzu vines, and Zebra mussels among numerous others, most notably domesticated animals.[19][20]

Human effects on biogeochemical pathways in the urban landscape

Urbanization results in a large demand for chemical use by industry, construction, agriculture, and energy providing services. Such demands have a substantial impact on biogeochemical cycles, resulting in phenomena such as acid rain, eutrophication, and global warming.[10] Furthermore, natural biogeochemical cycles in the urban environment can be impeded due to impermeable surfaces that prevent nutrients from returning to the soil, water, and atmosphere.[21]

Demand for fertilizers to meet agricultural needs exerted by expanding urban centers can alter chemical composition of soil. Such effects often result in abnormally high concentrations of compounds including sulfur, phosphorus, nitrogen, and heavy metals. In addition, nitrogen and phosphorus used in fertilizers have caused severe problems in the form of agricultural runoff, which alters the concentration of these compounds in local rivers and streams, often resulting in adverse effects on native species.[22] A well-known effect of agricultural runoff is the phenomenon of eutrophication. When the fertilizer chemicals from agricultural runoff reach the ocean, an algal bloom results, then rapidly dies off.[22] The dead algae biomass is decomposed by bacteria that also consume large quantities of oxygen, which they obtain from the water, creating a ‘dead zone’ without oxygen for fish or other organisms. A classic example is the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico due to agricultural runoff into the Mississippi River.

Just as pollutants and alterations in the biogeochemical cycle alter river and ocean ecosystems, they exert likewise effects in the air. Smog stems from the accumulation of chemicals and pollution and often manifests in urban settings, which has a great impact on local plants and animals. Because urban centers are often considered point sources for pollution, unsurprisingly local plants have adapted to withstand such conditions.[10]

Urban effects on climate

Urban environments and outlying areas have been found to exhibit unique local temperatures, precipitation, and other characteristic activity due to a variety of factors such as pollution and altered geochemical cycles. Some examples of the urban effects on climate are urban heat island, oasis effect, green house gases, and acid rain. This further stirs the debate as to whether urban areas should be considered a unique biome. Despite common trends among all urban centers, the surrounding local environment heavily influences much of the climate. One such example of regional differences can be seen through the urban heat island and oasis effect.[14]

Urban heat island/ oasis effect

The urban heat island is a phenomenon in which central regions of urban centers exhibit higher mean temperatures than surrounding urban areas.[23] Much of this effect can be attributed to low city albedo, the reflecting power of a surface, and the increased surface area of buildings to absorb solar radiation.[14] Concrete, cement, and metal surfaces in urban areas tend to absorb heat energy rather than reflect it, contributing to higher urban temperatures. Brazel et al.[14] found that the urban heat island effect demonstrates a positive correlation with population density in the city of Baltimore. The heat island effect has corresponding ecological consequences on resident species.[10] However, this effect has only been seen in temperate climates.

On the other hand, cities in desert environments show a different trend known as the “urban oasis effect”. This effect is characterized by a cooler city center compared to the surrounding environments.[14] LTER data from Phoenix, Arizona have suggested the urban oasis effect.[14] Increased vegetation in urban areas has been proposed as the cause for this phenomenon.[14] The urban oasis effect contributes to a decrease in temperature in the urban area making it less optimal for the native species.

Greenhouse gases

Greenhouse gas emissions include those of carbon dioxide and methane from the combustion of fossil fuels to supply energy needed by vast urban metropolises. Other greenhouse gases include water vapor, nitrous oxide, and ozone. Increases in greenhouse gases due to urban transport, construction, industry and other demands have been correlated strongly with increase in temperature. Sources of methane are agricultural dairy cows [24][25] and landfills.[26]

Acid rain and pollution

Processes related to urban areas result in the emission of numerous pollutants, which change corresponding nutrient cycles of carbon, sulfur, nitrogen, and other elements.[27] Ecosystems in and around the urban center are especially influenced by these point sources of pollution. High sulfur dioxide concentrations resulting from the industrial demands of urbanization cause rainwater to become more acidic.[28][29] Such an effect has been found to have a significant influence on locally affected populations, especially in aquatic environments.[29] Wastes from urban centers, especially large urban centers in developed nations, can drive biogeochemical cycles on a global scale.[10]

Urban environment as an anthropogenic biome

The urban environment has been classified as an anthropogenic biome,[30] which is characterized by the predominance of certain species and climate trends such as urban heat island across many urban areas.[1][6] Examples of species characteristic of many urban environments include, cats, dogs, mosquitoes, rats, flies, and pigeons, which are all generalists.[31] Many of these are dependent on human activity and have adapted accordingly to the niche created by urban centers.

Biodiversity and urbanization

Species responses to the urban setting

Research thus far indicates that many species exhibit common trends of increased abundance and decreased diversity with increasing urbanization.[13][32] These effects have been observed in plant, spider, ant, and bird species.[13][32][33] Urban areas thus appear to be exerting a strong homogenizing effect on local species. This effect may stem from the homogeneity of the urban setting as designed by humans. The abundance and diversity of species thus reflects characteristics of the urban setting, indicating a low degree of diversity, which ultimately favors the success of generalists.[13][32][33]

Urban stream syndrome is a consistently observed trait of urbanization characterized by high nutrient and contaminant concentration, altered stream morphology, increased dominance of dominant species, and decreased biodiversity.[18][34] The two primary causes of urban stream syndrome are storm water runoff and wastewater treatment plant effluent.[10][34]

Edge effect and habitat corridors and fragmentation

Species diversity has been found to peak in fringe regions between urban and rural areas.[13][32][33] Human activity to a certain point does appear to increase local diversity in these edge areas, but high degrees of urbanization exert the aforementioned homogenizing effect, sharply lowering species diversity because of uniform habitat structures. Just as with increasing urbanization and increasing abundance but decreasing biodiversity, trends indicating high degrees of biodiversity were observed in ants, spiders, and birds.[13][32][33]

Landscape fragmentation and habitat loss in the urban environment is caused mainly by urban development.[35] Since habitat fragmentation is the subdivision of a large area of habitat into smaller isolated patches,[36] fragmentation is thought to have severe effects on the genetic structure of populations through population bottlenecks followed by erosion of genetic diversity, which results in fitness reduction and the inability of a population to respond to environmental changes.[37][38][39] Fragmentation causes habitats suited for a particular species to become separated by distances sufficient to prevent migration among populations by inhospitable terrain, such as roads, neighborhoods, and open parks, for said species.[40] There have been many studies examining the effects of fragmentation in amphibians, particularly the eastern red-backed salamander.[40] Noël et al.[40] found low genetic diversity in urban fragments of Montréal, Canada, which threaten the long-term survival of the populations of red-back salamanders, especially in the light of continued residential and commercial development projects and habitat degradation. Some efforts have been proposed to establish species corridors, continuous or near-continuous segments of habitat through urban and surrounding areas to minimize the disturbances imposed on ecosystems by urban stress and fragmentation. The I-90 Snoqualmie Pass Wildlife Corridor Project in Washington is one example of efforts to connect habitats separated by highways.[41]

Civil engineering and sustainability in the urban environment

Cities should be planned and constructed in such a way that minimizes the urban effects on the surrounding environment (urban heat island, precipitation, etc.) as well as optimizing ecological activity. For example, increasing the albedo, or reflective power, of surfaces in urban areas, can minimize urban heat island,[42][43] resulting in a lower magnitude of the urban heat island effect in urban areas. By minimizing these abnormal temperature trends and others, ecological activity would likely be improved in the urban setting.[1][44]

Need for remediation

Urbanization has indeed had a profound effect on the environment, on both local and global scales. Difficulties in actively constructing habitat corridor and returning biogeochemical cycles to normal raise the question as to whether such goals are feasible. However, some groups are working to return areas of land affected by the urban landscape to a more natural state.[45] This includes using landscape architecture to model natural systems and restore rivers to pre-urban states.[45]

Sustainability

With the ever-increasing demands for resources necessitated by urbanization, recent campaigns to move toward sustainable energy and resource consumption, such as LEED certification of buildings, Energy Star certified appliances, and zero emission vehicles, have gained momentum. Sustainability reflects techniques and consumption ensuring reasonably low resource use as a component of urban ecology. Techniques such as carbon recapture may also be used to sequester carbon compounds produced in urban centers rather continually emitting more of the greenhouse gas.[46]

Summary

Urbanization results in a series of both local and far-reaching effects on biodiversity, biogeochemical cycles, hydrology, and climate, among many other stresses. Many of these effects are not fully understood, as urban ecology has only recently emerged as a scientific discipline and much more research remains to be done. Observations on the impact of urbanization on biodiversity and species interactions are consistent across many studies but definitive mechanisms have yet to be established. Urban ecology constitutes an important and highly relevant subfield of ecology, and further study must be pursued to more fully understand the effects of human urban areas on the environment.

See also

- Carbon dioxide

- Global warming

- Habitat

- Landscape ecology

- Urban Ecology (journal)

- Urban forestry

- Zebra mussel

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Niemela, J. Ecology and urban planning. Biodiversity and Conservation. 1999. 8: 119-131.

- ↑ United Nations 2007. World urbanization prospects: the 2007 revision. UN.

- ↑ Pelt JM. (1977) L'Homme re-naturé. 1977. Eds Seuil. ISBN 2-02-004589-3 (French)

- ↑ Davis BNK. Urbanisation and the diversity of insects. In: Mound L A and Walo N (eds) Diversity of Insect Faunas. Symposia of the Royal Entomological Society of London. 1978. 9: 126-138. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford.

- ↑ Sukopp H, Blume HP and Kunick W (1979) The soil, flora and vegetation of Berlin's wastelands. In: Laurie I C (ed) Nature in Cities. 115-132. John Wiley, Chichester

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Forman, R.T.T. and M. Godron. Landscape ecology. 1986. John Wiley and Sons. New York, NY. 619.

- ↑ Wittig, R. and H. Sukopp. Was ist Stadtokologie? Stadtokologie. 1993. 1-9. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart

- ↑ Pickett STA, Burch WR Jr, Dalton SE, Foresman TW, Grove JM and Rowntree R A conceptual framework for the study of human ecosystems in urban areas. Urban Ecosystems. (1997b). 1:185-199.

- ↑ Furness, R.W., D.R. Thompson, and P.H. Becker. Spatial and temporal variation in mercury contamination of seabirds in the North Sea. Helgolander Meeresuntersuchungen. 1995. 49: 605-615.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Grimm, N.B., S.H. Faeth, N. E. Golubiewski, C.L. Redman, J. Wu., X. Bai, and J.M. Briggs. 2008. Global change and ecology of cities. Science 319:756-760.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Gallo, K.P., A.L. McNab, T.R. Karl, J.F. Brown, J.J. Hood, and J.D. Tarpley. The Use of NOAA AVHRR Data for Assessment of the Urban Heat Island Effect. American Meteorological Society. 1993. 32: 899-908.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Roth, M., T.R. Oke, and W.J. Emery. Satellite-derived urban heat island from three coastal cities and the utilization of such data in urban climatology. International Journal of Remote Sensing. 1989. 10(11): 1699-1720.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Schochat, E., W.L. Stefanov, M.E.A. Whitehouse, and S.H. Faeth. 2004. Urbanization and spider diversity: influences of human modification of habitat structure and productivity. Ecological Applications 14:268-280.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 Brazel, A., N. Selover, R. Vose, and G. Heisler. 2000. The tale of two climates-Baltimore and Phoenix urban LTER sites. Climate Research 15:123-135.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Hill, L. The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History. Lake Claremont Press. 2000.

- ↑ Changnon, S.A. Inadvertent Weather Modification in Urban Areas: Lessons for Global Climate Change. American Meteorological Society. 1992. 73(5): 619-627.

- ↑ Rudel, T.K., R. Defries, G.P. Asner, W.F. Laurance. “Changing Drivers Deforestation and New Opportunities for Conservation”. Conservation Biology. 2009. 23:1396-1405.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Paul, M.J. and J.L. Meyer. Streams in the urban landscape. Annual Review of Ecology and Ssystematic. 2001. 32: 333-365.

- ↑ Ewel, J.J., D.J. O’Dowd, J. Bergelson, C.C. Daehler, and C.M. D’Antonio, L. D. Gomez, and D. R. Gordon, R.J. Hobbs, A. Holt, K.R. Hopper, C.E. Hughes, M. LaHart, R.R.B. Leakey, W.G. Lee, L.L. Loope, D.H., Lorence, S.M. Louda, A.E. Lugo, P.B. McEvoy, D.M. Richardson, and P.M. Vitousek. Deliberate Introductions of Species: Research Needs. Bioscience. 1999. 49(8): 619-630.

- ↑ Colautti, R.I. and H.J. MacIsaac. A neutral terminology to define ‘invasive’ species. Diversity Distrib. 2004. 10:135-141.

- ↑ Kaye, J.P., P.M. Groffman, N.B. Grimm, L.A. Baker, and R.V. Pouyat. A distinct urban biogeochemistry? Trends Ecol Evol. 2006. 21(4): 192-199.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Roach, W.J., and N.B. Grimm. Nutrient variation in an urban lake chain and its consequences for phytoplankton production. J Environ Qual. 2009. 38(4): 1429-1440.

- ↑ Bornstein, R. and Q. Lin. Urban heat islands and summertime convective thunderstorms in Atlanta: three case studies. Atmospheric Environment. 2000. 34: 507-516.

- ↑ Benchaar, C., J. Rivest, C. Pomar, and J. Chiquette. Prediction of methane production from dairy cows using existing mechanistic models and regression equations. Journal of Animal Science. 1998. 76(2): 617-627.

- ↑ Moe, P.W. and H.F. Tyrrell. Methane Production in Dairy Cows. Journal of Dairy Science. 1979. 62(10): 1583-1586.

- ↑ Daley, E.J., I.J. Wright, and R.E. Spitzka. Methane Production from Landfills: An introduction. American Chemical Society. 1981. 144(14): 279-292.

- ↑ Lohse, K.A., D. Hope, R. Sponseller, J.O. Allen, and N.B. Grimm. Atmospheric deposition of carbon and nutrients across an arid metropolitan area. Sci Total Environ. 2008. 402(1):95-105.

- ↑ Chen, J. Rapid urbanization in China: A real challenge to soil protection and food security. CATENA. 2007. 69(1): 1-15.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Singh, A. and M. Agrawal. Acid rain and its ecological consequences. J Environ Biol. 2008. 29(1): 15-24.

- ↑ Ellis, E.C. and N. Ramankutty. Putting people in the map: anthropogenic biomes of the world. Front Ecol Environ. 2008. 6(8): 439-447.

- ↑ Wilby, R.L. and G.L.W. Perry. Climate change, biodiversity and the urban environment: a critical review based on London, UK. Physical Geography. 2006. 30(1): 73-98.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 Bradley, C.A., S.E.J. Gibbs, and S. Altizer. 2008. Urban land use predicts West Nile Virus exposure in songbirds. Ecological Applications 18:1083-1092.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Sanford, M.P., P.N. Manley, and D.D. Murphy. Effects of Urban Development on Ant Communities: Implications for Ecosystem Services and Management. Conservation Biology. 2008. 23(1): 131-141.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Walsh, C.J., A.H. Roy, J.W. Feminella, P.D. Cottingham, P.M. Groffman, and R.P. Morgan II. The urban stream syndrome: current knowledge and the search for a cure. J.N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2005. 24(3):706-723.

- ↑ Miller, J.R. and R.J. Hobbs. Conservation where people live and work. Conserv Biol. 2002. 16: 330-337.

- ↑ Wilcove, D.S., C.H. McLellan, and A.P. Dobson. Habitat fragmentation in the temperate zone. In: Soulé ME (ed) Conservation biology. Sinauer, Sunderland. 1986. 237-256.

- ↑ Young, A., T. Boyle, and T. Brown. The population genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation for plants. Trends Ecol Evol. 1996. 11: 413-418.

- ↑ Reed, D.H. and R. Frankham. Correlation between fitness and genetic diversity. Conserv Biol. 2003. 17: 230-237.

- ↑ Reed, D.H. and G.R. Hobbs. The relationship between population size and temporal variability in population size. Anim Conserv. 2004. 7:1-8.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Noël, S., M. Ouellet, P. Galois, and F.J. Lapointe. Impact of urban fragmentation on the genetic structure of the eastern red-backed salamander. Conserv Genet. 2007. 8:599-606.

- ↑ "TransWild Alliance". TransWild Alliance. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ Rosenfeld, A.H., J.J. Romm, H. Akbari, and A.C. Lloyd. Painting the town White — and Green. Technology Review. 1997. 52(8). [A version of this article is also available at: <http://EETD.LBL.gov/HeatIsland/PUBS/PAINTING/> ]

- ↑ Rosenfeld, A. H., H. Akbari, J. J. Romm, and M. Pomerantz. Cool Communities: Strategies for Heat Island Mitigation and Smog Reduction. Energy and Buildings. 1998. 28: 51-62.

- ↑ Felson, A.J. and S.T.A. Pickett. Designed experiments: new approaches to studying urban ecosystems. Front Ecol Envrion. 2005. 3(10): 549-556.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Blum, A. The Long View: Urban Remediation through Landscape and Architecture. Metropolis Mag. 2008. 92-95

- ↑ Nowak, D.J., and D.E. Crane. Carbon Storage and Sequestration By Urban Trees In the USA. Environmental Pollution. 2002. 116: 381–389.