Uracil-DNA glycosylase

Uracil-DNA glycosylase, also known as UNG or UDG, is a human gene[1] though orthologs exist ubiquitously among prokaryotes and eukaryotes and even in some DNA viruses. The first uracil DNA-glycosylase was isolated from Escherichia coli.[2] The human gene encodes one of several uracil-DNA glycosylases. Alternative promoter usage and splicing of this gene leads to two different isoforms: the mitochondrial UNG1 and the nuclear UNG2.[1] One important function of uracil-DNA glycosylases is to prevent mutagenesis by eliminating uracil from DNA molecules by cleaving the N-glycosylic bond and initiating the base-excision repair (BER) pathway. Uracil bases occur from cytosine deamination or misincorporation of dUMP residues. After a mutation occurs, the mutagenic threat of uracil propagates through any subsequent DNA replication steps.[3] Once unzipped, mismatched guanine and uracil pairs are separated, and DNA polymerase inserts complementary bases to form a guanine-cytosine (GC) pair in one daughter strand and an adenine-uracil (AU) pair in the other.[4] Half of all progeny DNA derived from the mutated template inherit a shift from GC to AU at the mutation site.[4] UDG excises uracil in both AU and GU pairs to prevent propagation of the base mismatch to downstream transcription and translation processes.[4] With high efficiency and specificity, this glycosylase repairs more than 10,000 bases damaged daily in the human cell.[5] Human cells express five to six types of DNA glycosylases, all of which share a common mechanism of base eversion and excision as a means of DNA repair.[6]

Structure

UDG is made of a four-stranded parallel β-sheet surrounded by eight α-helices.[7] The active site comprises five highly conserved motifs that collectively catalyze glycosidic bond cleavage:[8][9]

1) Water-activating loop: 63-QDPYH-67[9]

2) Pro-rich loop: 165-PPPPS-169[7]

3) Uracil-binding motif: 199-GVLLLN-204[7][8]

4) Gly-Ser loop: 246-GS-247[7]

5) Minor groove intercalation loop: 268-HPSPLS-273[7][8]

Mechanism

Glycosidic bond cleavage follows a “pinch-push-pull” mechanism using the five conserved motifs.[7]

Pinch: UDG scans DNA for uracil by nonspecifically binding to the strand and creating a kink in the backbone, thereby positioning the selected base for detection. The Pro-rich and Gly-Ser loops form polar contacts with the 3’ and 5’ phosphates flanking the examined base.[8] This compression of the DNA backbone, or “pinch,” allows for close contact between UDG and base of interest.[7]

Push: To fully assess the nucleotide identity, the intercalation loop penetrates, or pushes into, the DNA minor groove and induces a conformational change to flip the nucleotide out of the helix.[10] Backbone compression favors eversion of the now extrahelical nucleotide, which is positioned for recognition by the uracil-binding motif.[7] The coupling of intercalation and eversion helps compensate for the disruption of favorable base stacking interactions within the DNA helix. Leu272 fills the void left by the flipped nucleotide to create dispersion interactions with neighboring bases and restore stacking stability.[8]

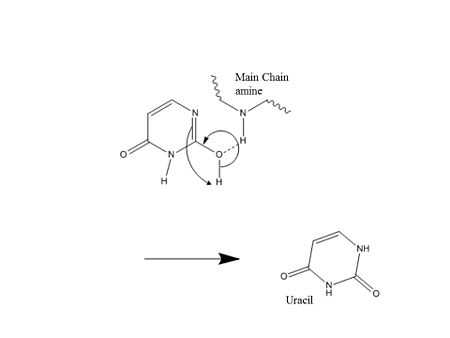

Pull: Now accessible to the active site, the nucleotide interacts with the uracil binding motif. The active site shape complements the everted uracil structure, allowing for high substrate specificity. Purines are too large to fit in the active site, while unfavorable interactions with other pyrimidines discourage binding alternative substrates.[6] The side chain of Tyr147 interferes sterically with the thymine C5 methyl group, while a specific hydrogen bond between the uracil O2 carbonyl and Gln144 discriminates against a cytosine substrate, which lacks the necessary carbonyl.[6] Once uracil is recognized, cleavage of the glycosidic bond proceeds according to the mechanism below.

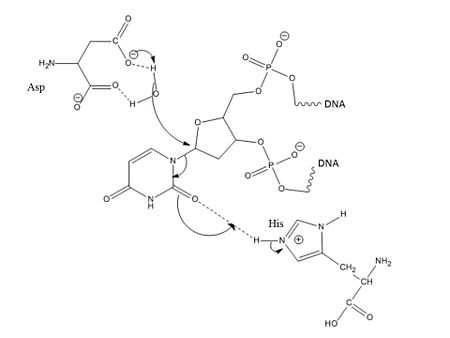

The position of the residues that activate the water nucleophile and protonate the uracil leaving group are widely debated, though the most commonly followed mechanism employs the water activating loop detailed in the enzyme structure.[9][11] Regardless of position, the identities of the aspartic acid and histidine residues are consistent across catalytic studies.[7][8][9][11][12]

Interactions

Uracil-DNA glycosylase has been shown to interact with RPA2.[13]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Entrez Gene: UNG uracil-DNA glycosylase".

- ↑ Lindahl T, Ljungquist S, Siegert W, Nyberg B, Sperens B (1977). "DNA N-glycosidases: properties of uracil-DNA glycosidase from Escherichia coli". J. Biol. Chem. 252 (10): 3286–94. PMID 324994.

- ↑ Longo, M. C.; Berninger, M. S.; Hartley, J. L. (1990). "Use of uracil DNA glycosylase to control carry-over contamination in polymerase chain reactions". Gene 93 (1): 125–128. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(90)90145-H. PMID 2227421.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Pearl, L. H. (2000). "Structure and function in the uracil-DNA glycosylase superfamily". Mutation research 460 (3–4): 165–181. doi:10.1016/S0921-8777(00)00025-2. PMID 10946227.

- ↑ Slupphaug, G.; Mol, C. D.; Kavli, B.; Arvai, A. S.; Krokan, H. E.; Tainer, J. A. (1996). "A nucleotide-flipping mechanism from the structure of human uracil–DNA glycosylase bound to DNA". Nature 384 (6604): 87–92. doi:10.1038/384087a0. PMID 8900285.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Lindahl, T. (2000). "Suppression of spontaneous mutagenesis in human cells by DNA base excision-repair". Mutation research 462 (2–3): 129–135. doi:10.1016/S1383-5742(00)00024-7. PMID 10767624.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Parikh, S. S.; Putnam, C. D.; Tainer, J. A. (2000). "Lessons learned from structural results on uracil-DNA glycosylase". Mutation research 460 (3–4): 183–199. doi:10.1016/S0921-8777(00)00026-4. PMID 10946228.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Zharkov, D. O.; Mechetin, G. V.; Nevinsky, G. A. (2010). "Uracil-DNA glycosylase: Structural, thermodynamic and kinetic aspects of lesion search and recognition". Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 685 (1–2): 11–20. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.10.017. PMC 3000906. PMID 19909758.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Acharya, N.; Kumar, P.; Varshney, U. (2003). "Complexes of the uracil-DNA glycosylase inhibitor protein, Ugi, with Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis uracil-DNA glycosylases". Microbiology (Reading, England) 149 (Pt 7): 1647–1658. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26228-0. PMID 12855717.

- ↑ Mol, C. D.; Arvai, A. S.; Slupphaug, G.; Kavli, B.; Alseth, I.; Krokan, H. E.; Tainer, J. A. (1995). "Crystal structure and mutational analysis of human uracil-DNA glycosylase: Structural basis for specificity and catalysis". Cell 80 (6): 869–878. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90290-2. PMID 7697717.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Schormann, N.; Grigorian, A.; Samal, A.; Krishnan, R.; Delucas, L.; Chattopadhyay, D. (2007). "Crystal structure of vaccinia virus uracil-DNA glycosylase reveals dimeric assembly". BMC Structural Biology 7: 45. doi:10.1186/1472-6807-7-45. PMC 1936997. PMID 17605817.

- ↑ Savva, R.; McAuley-Hecht, K.; Brown, T.; Pearl, L. (1995). "The structural basis of specific base-excision repair by uracil–DNA glycosylase". Nature 373 (6514): 487–493. doi:10.1038/373487a0. PMID 7845459.

- ↑ Nagelhus, T A; Haug T, Singh K K, Keshav K F, Skorpen F, Otterlei M, Bharati S, Lindmo T, Benichou S, Benarous R, Krokan H E (March 1997). "A sequence in the N-terminal region of human uracil-DNA glycosylase with homology to XPA interacts with the C-terminal part of the 34-kDa subunit of replication protein A". J. Biol. Chem. (UNITED STATES) 272 (10): 6561–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.10.6561. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 9045683.

Further reading

- Caradonna S, Muller-Weeks S (2002). "The nature of enzymes involved in uracil-DNA repair: isoform characteristics of proteins responsible for nuclear and mitochondrial genomic integrity". Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2 (4): 335–47. doi:10.2174/1389203013381044. PMID 12369930.

- Kino T, Pavlakis GN (2004). "Partner molecules of accessory protein Vpr of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1". DNA Cell Biol. 23 (4): 193–205. doi:10.1089/104454904773819789. PMID 15142377.

- Van Maele B, Debyser Z (2005). "HIV-1 integration: an interplay between HIV-1 integrase, cellular and viral proteins". AIDS reviews 7 (1): 26–43. PMID 15875659.

- Slupphaug G, Olsen LC, Helland D, et al. (1991). "Cell cycle regulation and in vitro hybrid arrest analysis of the major human uracil-DNA glycosylase". Nucleic Acids Res. 19 (19): 5131–7. doi:10.1093/nar/19.19.5131. PMC 328866. PMID 1923798.

- Muller SJ, Caradonna S (1991). "Isolation and characterization of a human cDNA encoding uracil-DNA glycosylase". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1088 (2): 197–207. doi:10.1016/0167-4781(91)90055-Q. PMID 2001396.

- Olsen LC, Aasland R, Wittwer CU, et al. (1990). "Molecular cloning of human uracil-DNA glycosylase, a highly conserved DNA repair enzyme". EMBO J. 8 (10): 3121–5. PMC 401392. PMID 2555154.

- Nagelhus TA, Slupphaug G, Lindmo T, Krokan HE (1995). "Cell cycle regulation and subcellular localization of the major human uracil-DNA glycosylase". Exp. Cell Res. 220 (2): 292–7. doi:10.1006/excr.1995.1318. PMID 7556436.

- Mol CD, Arvai AS, Sanderson RJ, et al. (1995). "Crystal structure of human uracil-DNA glycosylase in complex with a protein inhibitor: protein mimicry of DNA". Cell 82 (5): 701–8. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90467-0. PMID 7671300.

- Mol CD, Arvai AS, Slupphaug G, et al. (1995). "Crystal structure and mutational analysis of human uracil-DNA glycosylase: structural basis for specificity and catalysis". Cell 80 (6): 869–78. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90290-2. PMID 7697717.

- Haug T, Skorpen F, Lund H, Krokan HE (1994). "Structure of the gene for human uracil-DNA glycosylase and analysis of the promoter function". FEBS Lett. 353 (2): 180–4. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)01042-0. PMID 7926048.

- Slupphaug G, Markussen FH, Olsen LC, et al. (1993). "Nuclear and mitochondrial forms of human uracil-DNA glycosylase are encoded by the same gene". Nucleic Acids Res. 21 (11): 2579–84. doi:10.1093/nar/21.11.2579. PMC 309584. PMID 8332455.

- Bouhamdan M, Benichou S, Rey F, et al. (1996). "Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr protein binds to the uracil DNA glycosylase DNA repair enzyme". J. Virol. 70 (2): 697–704. PMC 189869. PMID 8551605.

- Kavli B, Slupphaug G, Mol CD, et al. (1996). "Excision of cytosine and thymine from DNA by mutants of human uracil-DNA glycosylase". EMBO J. 15 (13): 3442–7. PMC 451908. PMID 8670846.

- Haug T, Skorpen F, Kvaløy K, et al. (1997). "Human uracil-DNA glycosylase gene: sequence organization, methylation pattern, and mapping to chromosome 12q23-q24.1". Genomics 36 (3): 408–16. doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0485. PMID 8884263.

- Slupphaug G, Mol CD, Kavli B, et al. (1996). "A nucleotide-flipping mechanism from the structure of human uracil-DNA glycosylase bound to DNA". Nature 384 (6604): 87–92. doi:10.1038/384087a0. PMID 8900285.

- Nilsen H, Otterlei M, Haug T, et al. (1997). "Nuclear and mitochondrial uracil-DNA glycosylases are generated by alternative splicing and transcription from different positions in the UNG gene". Nucleic Acids Res. 25 (4): 750–5. doi:10.1093/nar/25.4.750. PMC 146498. PMID 9016624.

- Nagelhus TA, Haug T, Singh KK, et al. (1997). "A sequence in the N-terminal region of human uracil-DNA glycosylase with homology to XPA interacts with the C-terminal part of the 34-kDa subunit of replication protein A". J. Biol. Chem. 272 (10): 6561–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.10.6561. PMID 9045683.

- Selig L, Benichou S, Rogel ME, et al. (1997). "Uracil DNA glycosylase specifically interacts with Vpr of both human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus of sooty mangabeys, but binding does not correlate with cell cycle arrest". J. Virol. 71 (6): 4842–6. PMC 191711. PMID 9151883.

- Withers-Ward ES, Jowett JB, Stewart SA, et al. (1997). "Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr interacts with HHR23A, a cellular protein implicated in nucleotide excision DNA repair". J. Virol. 71 (12): 9732–42. PMC 230283. PMID 9371639.

- Haug T, Skorpen F, Aas PA, et al. (1998). "Regulation of expression of nuclear and mitochondrial forms of human uracil-DNA glycosylase". Nucleic Acids Res. 26 (6): 1449–57. doi:10.1093/nar/26.6.1449. PMC 147431. PMID 9490791.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||