Understeer and oversteer

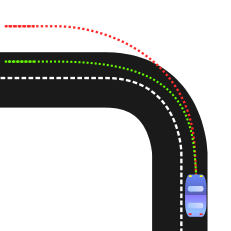

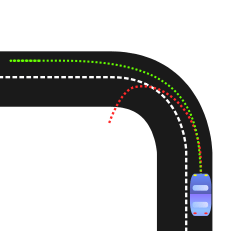

Understeer and oversteer are vehicle dynamics terms used to describe the sensitivity of a vehicle to steering. Simply put, oversteer is what occurs when a car turns (steers) by more than (over) the amount commanded by the driver. Conversely, understeer is what occurs when a car steers less than (under) the amount commanded by the driver.

Automotive engineers define understeer and oversteer based on changes in steering angle associated with changes in lateral acceleration over a sequence of steady-state circular turning tests. Car and motorsport enthusiasts often use the terminology more generally in magazines and blogs to describe vehicle response to steering in all kinds of maneuvers.

Vehicle dynamics terminology

Standard terminology used to describe understeer and oversteer are defined by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) in document J670[1] and by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in document 8855.[2] By these terms, understeer and oversteer are based on differences in steady-state conditions where the vehicle is following a constant-radius path at a constant speed with a constant steering wheel angle, on a flat and level surface.

Understeer and oversteer are defined by an understeer gradient K that is a measure of how the steering needed for a steady turn changes as a function of lateral acceleration. Steering at a steady speed is compared to the steering that would be needed to follow the same circular path at low speed. The low-speed steering for a given radius of turn is called Ackermann steer. The vehicle has a positive understeer gradient if the difference between required steer and the Ackermann steer increases with respect to incremental increases in lateral acceleration. The vehicle has a negative gradient if the difference in steer decreases with respect to incremental increases in lateral acceleration.

Understeer and oversteer are formally defined using the gradient K: if K is positive, the vehicle shows understeer; if K is negative, the vehicle shows oversteer; if K is zero, the vehicle is neutral.

Several tests can be used to determine understeer gradient: constant radius (repeat tests at different speeds), constant speed (repeat tests with different steering angles), or constant steer (repeat tests at different speeds). Formal descriptions of these three kinds of testing are provided by ISO.[3] Gillespie goes into some detail on two of the measurement methods.[4]

Results depend on the type of test, so simply giving a deg/g value is not sufficient; it is also necessary to indicate the type of procedure used to measure the gradient.

Vehicles are inherently nonlinear systems, and it is normal for K to vary over the range of testing. It is possible for a vehicle to be understeer in some conditions and oversteer in others. Therefore, it is necessary to specify the speed and lateral acceleration whenever reporting understeer/oversteer characteristics.

Contributions to understeer

Many properties of the vehicle affect the understeer gradient, including tire cornering stiffness, camber thrust, lateral force compliance steer, self aligning torque, lateral load transfer, and compliance in the steering system. These individual contributions can be identified analytically or by measurement in a Bundorf analysis.

Limit conditions

When an understeer vehicle is taken to frictional limits where it is no longer possible to increase lateral acceleration, the vehicle will follow a path with a radius larger than intended. Although the vehicle cannot increase lateral acceleration, it is dynamically stable.

When an oversteer vehicle is taken to frictional limits, it becomes dynamically unstable with a tendency to spin out. Although the vehicle is unstable in open-loop control, a skilled driver can maintain control a little past the point of instability with counter-steering. However, at some limit in lateral acceleration, it is not physically possible for even the most skilled driver to maintain a steady state and spinout will occur.

Related measures

Understeer gradient is one of the main measures for characterizing steady-state cornering behavior. It is involved in other properties such as characteristic speed (the speed for an understeer vehicle where the steer angle needed to negotiate a turn is twice the Ackerman angle), lateral acceleration gain (g's/deg), yaw velocity gain (1/s), and critical speed (the speed where an oversteer vehicle has infinite lateral acceleration gain).

References

- ↑ SAE International Surface Vehicle Recommended Practice, "Vehicle Dynamics Terminology", SAE Standard J670, Rev. 2008-01-24

- ↑ International Organization for Standardization, "Road vehicles – Vehicle dynamics and road-holding ability – Vocabulary", ISO Standard 8855, Rev. 2010

- ↑ International Organization for Standardization, "Passenger cars – Steady-state circular driving behaviour – Open-loop test methods", ISO Standard 4138

- ↑ T. D. Gillespie, "Fundamentals of Vehicle Dynamics", Society of Automotive Engineers, Inc., Warrendale, PA, 1992. pp 226–230

| ||||||||