Uncle Tom's Children

| Uncle Tom's Children | |

|---|---|

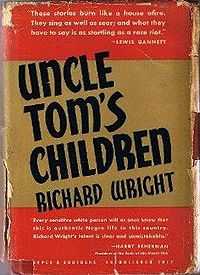

1st edition cover with quote from Harry Scherman | |

| Author | Richard Wright |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Short story |

| Publisher | Harper |

Publication date | 1938 and reissued 1940. |

| Pages | 317 |

Uncle Tom's Children is a collection of short stories by African American author Richard Wright, also the author of Black Boy, Native Son, and The Outsider. Uncle Tom's Children includes four short stories and was successful when it was first published in 1938. In 1940, Harper reissued the volume as Uncle Tom's Children: Five Long Stories, incorporating "Bright and Morning Star" as well as placing "The Ethics of Living Jim Crow" as the text's introduction. The Harper Perennial edition of Wright's novel Black Boy, under the heading 'Books by Richard Wright', misprints "Uncle Tom's Children" as "Uncle Tom's Cabin".

Plot

The Ethics of Living Jim Crow

"The Ethics of Living Jim Crow" describes Wright's own experiences growing up. The essay starts with his first encounter with racism, when his attempt to play a war game with white children turns ugly, and follows his experiences with the problems of being black in the South through his adolescence and adulthood. It describes his experience of prejudice at his first job. While working at an optical factory, his white fellow employees bully and eventually beat him for wanting to learn job skills that could allow him to advance. Wright also discusses suffering attacks by white youths and explores the many hypocrisies of white prejudice against blacks. These include black men being allowed to work around naked white prostitutes while having to pretend they do not exist. Whites have exploitative sex with black maids, and yet any sexual relations between a black man and a white woman, even a prostitute, is cause for castration or death. Wright also delves into the more subtle humiliations inherent in the Jim Crow system, such as being unable to say "thank you," to a white man, lest he take it as a statement of equality.

Big Boy Leaves Home

Big Boy was chosen to be the leader of his friends. One day, Big Boy and friends Bobo, Lester, and Buck decide to go swimming in a restricted area. They take off their clothes and proceed to play in the water. Soon, a white woman comes upon them and the boys are unable to get their clothes without being seen. After reacting to the boys with shock and disgust, she calls for "Jim". Jim quickly appears and, feeling threatened, proceeds to kill Lester and Buck. After a short struggle between Big Boy and Jim, Big Boy takes control of the rifle and shoots Jim, seemingly killing him. The remaining two members of the group quickly gather their clothes and flee the scene. The story moves with Big Boy as he makes his way back home. He relates the story to his family. All the while, Big Boy is terrified that the white people will form a mob and lynch him. The family has an acquaintance who drives a truck and can help Big Boy escape. Big Boy is sent off with some food while he waits for the acquaintance to leave with the truck at 6:00 AM the next morning. As he finds a place to settle for a while, he overhears some white men discussing the search situation and learns that they've captured Bobo, the other surviving boy of the original group of four. Bobo is burned at the stake. Later, the acquaintance, Will, finds Big Boy and they head off in the truck. The story ends in bittersweet fashion as Big Boy thinks about the slaughter of his friends in the new sunny day.

Down by the Riverside

"Down by the Riverside" takes place during a major flood. Its main character, a farmer named Mann, must get his family to safety in the hills, but he does not have a boat. In addition, his wife, Lulu, has been in labor for several days but cannot deliver the baby. Mann must get her to a hospital - the Red Cross hospital. He has sent his cousin Bob to sell a donkey and use the money to buy a boat, but Bob returns with only fifteen dollars from the donkey and a stolen boat. Mann must take the boat through town to the hospital, even though Bob advises against this, since the boat is very recognizable. Rowing his family, including Lulu, Peewee, his son and Grannie, Lulu's mother, in this white boat, Mann calls for help at the first house he reaches. This house is the home of the boat's white owner, Heartfield, who immediately begins shooting. Mann, who has brought his gun, returns fire and kills the man, while the man's family witnesses the act from the windows of the house.

Mann rows on to the Red Cross hospital but is too late; Lulu and the undelivered baby have died. Soldiers take away Grannie and Peewee to safety in the hills, and Mann is conscripted to work on the failing levee. However, the levee breaks, and Mann must return to the hospital, where he smashes a hole in the ceiling at the direction of a colonel - who then directs Mann to find him once everything's over saying he'll help Mann if he can - allowing the hospital to be evacuated. Mann and a young black boy, Brinkley, are told to rescue a family at the edge of town, who turn out to be the Heartfields. Inside the house, Heartfield's son recognizes Mann as his father's killer and Mann raises his axe thinking to kill the children & their mother but is stopped when the house shifts in the rising flood waters. Despite his terror that he might be fingered as Heartfield's murderer and accordingly facing the possibility of a brutal and torturous death, Mann takes the boy, the boy's sister and his mother to "the hills" and safety. There, Mann tries to blend with "his people", hoping he might find his family, until the white boy identifies Mann as the killer of his father. Armed soldiers take Mann away after tribunal with the general and then the colonel he'd helped at the Red Cross. Knowing he's doomed and vowing to "die fo they kill [him]" Mann runs and the soldiers shoot him dead by the river's edge.

Long Black Song

Fire and Cloud

"Fire and Cloud" follows a preacher, Taylor, as he tries to save his people from a wave of starvation. Denied food aid by the white authorities, Taylor must return empty-handed to his church. There he finds a tricky problem. He has been talking about marching in a demonstration with communists, and they have come to visit him in one room. In another room, the mayor and the police chief have arrived to talk to him. Taylor has a history with the mayor, who has done him favors in exchange for his securing peace and order among the black community. However, if the mayor finds out about the communists, Taylor will be in trouble. First Taylor talks to the communists, who try to convince him to further commit to marching by adding his name to the pamphlets they distribute. Taylor gives them only vague answers. He then talks to the mayor and the sheriff, who try to convince him not to march. Again, Taylor is unsure of what to do as he feels that adding his name will threaten not only himself but his community. He successfully gets both groups out of the church without their paths crossing. Then he talks to his deacons. One among them, Deacon Smith, has been plotting to depose Taylor and take over the church.

A car pulls up, and Taylor leaves the deacons to see who is in the car. Whites beat him and throw him in the back, taking him out to the woods. There, they whip him and make him recite the Lord's Prayer, in a move designed to keep him from marching. Taylor must walk back through a white neighborhood, where a policeman stops him but does not arrest him. Once home, Taylor realizes that this beating directly connects him to the suffering of his people, and he tells his son that the march must go on. Seeing that many in his congregation have also been beaten over the night, Taylor leads them in the march through town. He realizes that together, the pain of his being whipped and the strength of the assembled marchers, black and white people in one crowd, are a sign from God. The whipping is fire, and the crowd is the cloud of the fire and the cloud God used to lead the Hebrews to the Promised Land.

Bright and Morning Star

"Bright and Morning Star" concerns an old woman, Sue, whose sons are communist party organizers. One son, Sug, has already been imprisoned for this and does not appear in the story. Sue waits for the other son, Johnny-Boy, to arrive home when the story begins. Though she is no longer a Christian, believing instead in a communist vision of the human struggle, Sue finds herself singing an old hymn as she waits. A white fellow communist, Reva, the daughter of a major organizer, Lem, stops by to tell Sue that the sheriff has discovered plans for a meeting at Lem's and that the comrades must be told or they will be caught. Someone in the group has become an informer. Reva departs, and Johnny-Boy comes home. Sue feeds him dinner, and they discuss her mistrust of white fellow-communists. Then, she sends him out to tell the comrades not to go to Lem's for the meeting.

The sheriff shows up at Sue's looking for Johnny-Boy. The sheriff threatens Sue, saying that if she does not get him to talk, she had best bring a sheet to get his body. Sue speaks defiantly to the sheriff, who slaps her around but starts to leave. Then Sue shouts after him from the door, and he returns, this time beating her badly. In her weakened state, she reveals the comrades' names to Booker, a white communist who is actually the sheriff's informer. Sue realizes that she is the only one left who can save the comrades, and she dedicates herself completely to this task. Remembering the sheriff's words, she takes a white sheet and wraps a gun in it. She goes through the woods until she finds the sheriff, who has caught Johnny-Boy. The sheriff tortures Johnny-Boy before her eyes, but she does not relent or try to get Johnny-Boy to give up. Then Booker shows up, and she shoots him through the sheet. The sheriff's men shoot first Johnny-Boy and then Sue dead. As she lies on the ground, she realizes she has fulfilled her purpose in life.

Literary significance and criticism

The stories won high critical praise; what one critic had to say of them is characteristic: "Uncle Tom's Children has its full share of violence and brutality; violent deaths occur in three stories and the mob goes to work in all four. Violence has long been an important element in fiction about Negroes, just as it is in their life. But where Julia Peterkin in her pastorals and Roark Bradford in his levee farces show violence to be the reaction of primitives unadjusted to modern civilization, Richard Wright shows it as the way in which civilization keeps the Negro in his place. And he knows what he is writing about."[1]

References

- Yarborough, Richard. "Introduction." Uncle Tom's Children. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2008.

Notes

External links

- Online text of Uncle Tom's Children at Google