Umbria

| Umbria ' | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region of Italy | |||

| |||

| |||

| Country | Italy | ||

| Capital | Perugia | ||

| Government | |||

| • President | Catiuscia Marini (PD) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 8,456 km2 (3,265 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2012-10-30) | |||

| • Total | 885,535 | ||

| • Density | 100/km2 (270/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| GDP/ Nominal | €21.8[1] billion (2008) | ||

| GDP per capita | €24,400[2] (2008) | ||

| NUTS Region | ITE | ||

| Website | "Regione Umbria: sito istituzionale" (in Italian). | ||

Umbria (Italian pronunciation: [ˈumbrja]), is a region of historic and modern central Italy. It is the only region having neither a coastline nor a common border with other countries; however, the region includes the Lake Trasimeno and is crossed by the River Tiber. The regional capital is Perugia. Umbria is appreciated for its landscapes, traditions, history, artistic legacy and influence on high culture.

The region is characterized by sweet and green hills and historical towns such as Assisi (a World Heritage Site associated with St. Francis of Assisi, the Basilica of San Francesco and other Franciscan sites, with works by Giotto and Cimabue), Norcia (the hometown of St. Benedict), Gubbio, Spoleto, Todi, Città di Castello, Orvieto, Cascata delle Marmore, Castiglione del Lago, Passignano sul Trasimeno and other charming towns and small cities.

Geography

Umbria is bordered by Tuscany to the west, Marche to the east and Lazio to the south. Partly hilly and partly flat, and fertile for being crossed by the valley of the Tiber, its topography includes part of the central Apennines, with the highest point in the region at Monte Vettore on the border of the Marche, at 2,476 m (8,123 ft); the lowest point is Attigliano, 96 m (315 ft). It is the only Italian region having neither a coastline nor a common border with other countries.

The Tiber River forms the approximate border with Lazio, although its source is just over the Tuscan border. The Tiber's three principal tributaries flow southward through Umbria. The Chiascio basin is relatively uninhabited as far as Bastia Umbra. About 10 km (6 mi) farther on, it joins the Tiber at Torgiano. The Topino, cleaving the Apennines with passes that the Via Flaminia and successor roads follow, makes a sharp turn at Foligno to flow NW for a few kilometres before joining the Chiascio below Bettona. The third river is the Nera, flowing into the Tiber further south, at Terni; its valley is called the Valnerina. The upper Nera cuts ravines in the mountains; the lower, in the Chiascio-Topino basin, has created a wide floodplain.

In antiquity, the plain was covered by a pair of shallow, interlocking lakes, the Lacus Clitorius and the Lacus Umber. They were drained by the Romans over several hundred years. An earthquake in the 4th century and the political collapse of the Roman Empire resulted in the reflooding of the basin. It was drained a second time, almost a thousand years later, during a 500-year period: Benedictine monks started the process in the 13th century, and the draining was completed by an engineer from Foligno in the 18th century.

In literature, Umbria is referred to as il cuor verde d'Italia (the green heart of Italy). The phrase is taken from a poem by Giosuè Carducci, the subject of which is the source of the Clitunno River in Umbria.

History

The region is named for the Umbri tribe, one of those who were absorbed by the expansion of the Romans. Pliny the Elder recounted a fanciful derivation for the tribal name from the Greek ὄμβρος "a shower", which had led to the confused idea that they had survived the Deluge familiar from Greek mythology, giving them the claim to be the most ancient race in Italy.[3] In fact they belonged to a broader family of neighbouring tribes with similar roots. Their language was Umbrian, one of the Italic languages, related to Latin and Oscan.

The Umbri probably sprang, like neighbouring tribes, from the creators of the Terramara, and Villanovan culture in northern and central Italy, who entered north-eastern Italy at the beginning of the Bronze Age.

The Etruscans were the chief enemies of the Umbri. The Etruscan invasion went from the western seaboard towards the north and east (lasting from about 700 to 500 BC), eventually driving the Umbrians towards the Apennine uplands and capturing 300 Umbrian towns. Nevertheless, the Umbrian population does not seem to have been eradicated in the conquered districts.

After the downfall of the Etruscans, Umbrians aided the Samnites in their struggle against Rome (308 BC). Later communications with Samnium were impeded by the Roman fortress of Narni (founded 298 BC). Romans defeated the Samnites and their Gallic allies in the battle of Sentinum (295 BC). Allied Umbrians and Etruscans had to return to their territories to defend against simultaneous Roman attacks, so were unable to help the Samnites in the battle of Sentium.

The Roman victory at Sentinum started a period of integration under the Roman rulers, who established some colonies (e.g., Spoletium) and built the via Flaminia (220 BC). The via Flaminia became a principal vector for Roman development in Umbria. During Hannibal's invasion in the second Punic war, the battle of Lake Trasimene was fought in Umbria, but the Umbrians did not aid the invader.

During the Roman civil war between Mark Antony and Octavian (40 BC), the city of Perugia supported Antony and was almost completely destroyed by Octavian.

In Pliny the Elder's time, 49 independent communities still existed in Umbria, and the abundance of inscriptions and the high proportion of recruits in the imperial army attest to its population.

The modern region of Umbria is different from the Umbria of Roman times (see Roman Umbria). Roman Umbria extended through most of what is now the northern Marche, to Ravenna, but excluded the west bank of the Tiber. Thus Perugia was in Etruria, and the area around Norcia was in the Sabine territory.

After the collapse of the Roman empire, Ostrogoths and Byzantines struggled for the supremacy in the region. The Lombards founded the duchy of Spoleto, covering much of today's Umbria. When Charlemagne conquered most of the Lombard kingdoms, some Umbrian territories were given to the Pope, who established temporal power over them. Some cities acquired a form of autonomy (the comuni). These cities were frequently at war with each other, often in a context of more general conflicts, either between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire or between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines.

In the 14th century, the signorie arose, but were subsumed into the Papal States. The Papacy ruled the region until the end of the 18th century.

After the French Revolution and the French conquest of Italy, Umbria became part of the ephemeral Roman Republic (1798–1799) and later, part of the Napoleonic Empire (1809–1814).

After Napoleon's defeat, the Pope regained Umbria and ruled it until 1860.

Following the Risorgimento, the expansion of the Piedmontese, and Italian unification, in 1861, Umbria was incorporated in the Kingdom of Italy.

The present borders of Umbria were fixed in 1927, with the creation of the province of Terni and the separation of the province of Rieti, which was incorporated into Lazio.

In 1946 Umbria became part of the Italian Republic.

Economy

The present economic structure emerged from a series of transformations which took place mainly in the 1970s and 1980s. During this period, there was rapid expansion among small and medium-sized firms and a gradual retrenchment among the large firms which had hitherto characterised the region's industrial base. This process of structural adjustment is still going on.[4]

Umbrian agriculture is noted for its tobacco, olive oil and vineyards, which produce excellent wines. Regional varietals include the white Orvieto, which draws agri-tourists to the vineyards in the area surrounding the medieval town of the same name.[5] Other noted wines produced in Umbria are Torgiano and Rosso di Montefalco. Another typical Umbrian product is the black truffle found in Valnerina, an area that produces 45% of this product in Italy.[4]

The food industry in Umbria produces processed pork-meats, confectionery, pasta and the traditional products of Valnerina in preserved form (truffles, lentils, cheese). The other main industries are textiles, clothing, sportswear, iron and steel, chemicals and ornamental ceramics.[4]

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1861 | 442,000 | — |

| 1871 | 479,000 | +8.4% |

| 1881 | 497,000 | +3.8% |

| 1901 | 579,000 | +16.5% |

| 1911 | 614,000 | +6.0% |

| 1921 | 658,000 | +7.2% |

| 1931 | 696,000 | +5.8% |

| 1941 | 723,000 | +3.9% |

| 1951 | 804,000 | +11.2% |

| 1961 | 795,000 | −1.1% |

| 1971 | 776,000 | −2.4% |

| 1981 | 808,000 | +4.1% |

| 1991 | 812,000 | +0.5% |

| 2001 | 826,000 | +1.7% |

| 2011 | 883,000 | +6.9% |

| Source: ISTAT 2001 | ||

As of 2008, the Italian national institute of statistics ISTAT estimated that 75,631 foreign-born immigrants live in Umbria, equal to 8.5% of the total population of the region.

Government and politics

Umbria was a former stronghold of the Italian Communist Party, forming with Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna and Marche the famous Italian political "Red Quadrilateral". Nowadays Umbria is a stronghold of the center-left and of the Democratic Party. At the April 2008 elections, Umbria gave more than 47% of its votes to Walter Veltroni.

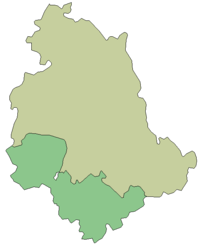

Administrative divisions

Umbria is divided into two provinces:

| Province | Area (km²) | Area (sq mi) | Population | Density (per km²) | Density (per sq mi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of Perugia | align="center"|6,334 | 2,446 | 660,040 | align="center"|104 | 270 |

| Province of Terni | align="center"|2,122 | 819 | 232,311 | align="center"|109 | 280 |

References

- ↑ http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tgs00003&plugin=1

- ↑ EUROPA – Press Releases – Regional GDP per inhabitant in 2008 GDP per inhabitant ranged from 28% of the EU27 average in Severozapaden in Bulgaria to 343% in Inner London

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, 3.6; 3.19.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Eurostat". Circa.europa.eu. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ↑ "Sagrantino di Montefalco: From Umbria Comes The Best Red Wine You Never Tasted!". IntoWine.com.

Bibliography

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Umbria. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Umbria. |

- Thayer, William P. (2010). "Umbria: the 92 Comuni". University of Chicago. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||