Two-point discrimination

| Two-point discrimination | |

|---|---|

| Diagnostics | |

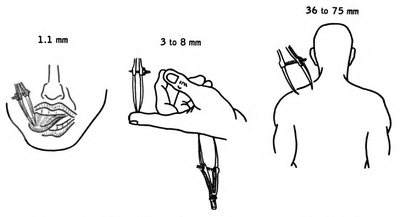

Differerent areas of the body have receptive fields of different sizes, giving some better resolution in two-point discrimationa. The tongue and fingers have very high resolution, while the back has very low. This is illustrated as the distance where the two points can be felt as separate (given in mm). |

Two-point discrimination is the ability to discern that two nearby objects touching the skin are truly two distinct points, not one. It is often tested with two sharp points during a neurological examination[1]:632[2]:71 and is assumed to reflect how finely innervated an area of skin is. In clinical settings, two-point discrimination is a widely used technique for determining tactile agnosia.[3] It relies on the ability and/or willingness of the patient to subjectively report what s/he is feeling and should be completed with the patient’s eyes closed.[4] The therapist may use calipers or simply a reshaped paperclip to do the testing. The therapist may alternate randomly between touching the patient with one point or with two points on the area being tested (e.g. finger, arm, leg, toe).[4] The patient is asked to report whether one or two points was felt. The smallest distance between two points that still results in the perception of two distinct stimuli is recorded as the patient's two-point threshold.[5] Performance on the two extremities can be compared for discrepancies.

Normal and Impaired Performance

Body areas differ both in tactile receptor density and somatosensory cortical representation. Normally, a person should be able to recognize two points separated by as little as 2–4 mm on the lips and finger pads, 8–15 mm on the palms and 30–40 mm on the shins or back (assuming the points are at the same dermatome).[1]:632 The posterior column-medial lemniscus pathway is responsible for carrying information involving fine, discriminative touch. Therefore, two-point discrimination can be impaired by damage to this pathway or to a peripheral nerve.[5]

Criticisms

Although it is commonly used clinically, two-point testing has often been criticized by researchers as a poor measure of tactile spatial acuity. It has been shown that two-point testing may have low sensitivity, failing to detect or underestimating sensory deficits.[6][7] Two-point testing has been criticized as well for yielding highly variable performance, for being reliant on the subjective criterion adopted by the patient for reporting "one" compared to "two," and for resulting in performance that is "too good to be true," in the sense that the measured two-point threshold can fall well under the spacing between tactile receptors in the skin.[8][9][10][11] Neurophysiological recordings have shown that two points evoke a different number of action potentials in the receptor population than one point does;[12] as a result, the two-point task presents a non-spatial response "magnitude" cue that may reveal the presence of two points compared to one point, even when the two points cannot be perceived distinctly.[11][13] As a result of these findings, one article on the two-point test goes so far as to be titled: "The two-point threshold: Not a measure of tactile spatial resolution".[13]

Alternative Tests

Several tactile tests have been proposed as rigorous replacements to the two-point test. In psychophysics research laboratories, a popular test of tactile spatial acuity is the grating orientation task (GOT).[8] Another test is the raised letter recognition task.[8] Recently, two-point orientation discrimination (2POD) has been proposed as an equally convenient but rigorous alternative to the traditional two point task; in this task the patient attempts to discern the orientation of two points of contact on the skin (e.g., whether the points are aligned along the finger or across the finger) rather than the presence of two points compared to one.[11] Unlike the traditional two-point task, the GOT and 2POD tasks are thought to result in more purely spatial measures of acuity - i.e., to perform these tasks, the participant must discern the spatial modulation of the discharge of underlying skin receptors, without the help of a response magnitude cue.[8][11]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bickley, Lynn; Szilagui, Peter (2007). Bates' Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking (9th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/0-7818-6718-0 |0-7818-6718-0 [[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]]]] Check

|isbn=value (help). - ↑ Blumenfield, Hal (2002). Neuroanatomy Through Clinical Cases. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer. ISBN 0-87893-060-4.

- ↑ Shooter, David (2005). "Use of two-point discrimination as a nerve repair assessment tool: Preliminary report". ANZ Journal of Surgery 75 (10): 866–868. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03557.x. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Blumenfeld, Hal (2010). Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-87893-058-6.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 O'Sullivan, Susan (2007). Physical Rehabilitation Fifth Edition. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. pp. 136–146. ISBN 978- 0-8036-1247-1.

- ↑ van Nes, SI; Faber, CG; Hamers, RM; Harschnitz, O; Bakkers, M; Hermans, MC; Meijer, RJ; van Doorn, PA; Merkies, IS; PeriNomS Study, Group (July 2008). "Revising two-point discrimination assessment in normal aging and in patients with polyneuropathies.". Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 79 (7): 832–4. PMID 18450792.

- ↑ Van Boven, RW; Johnson, KO (February 1994). "A psychophysical study of the mechanisms of sensory recovery following nerve injury in humans.". Brain : a journal of neurology. 117 ( Pt 1): 149–67. PMID 8149208.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Johnson, KO; Phillips, JR (December 1981). "Tactile spatial resolution. I. Two-point discrimination, gap detection, grating resolution, and letter recognition.". Journal of neurophysiology 46 (6): 1177–92. PMID 7320742.

- ↑ Stevens, JC; Patterson, MQ (1995). "Dimensions of spatial acuity in the touch sense: changes over the life span.". Somatosensory & motor research 12 (1): 29–47. PMID 7571941.

- ↑ Lundborg, G; Rosén, B (October 2004). "The two-point discrimination test--time for a re-appraisal?". Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland) 29 (5): 418–22. PMID 15336741.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Tong, J; Mao,O; Goldreich, D (2013). "Two-point orientation discrimination versus the traditional two-point test for tactile spatial acuity assessment". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7 (579).

- ↑ Vega-Bermudez, F; Johnson, KO (June 1999). "Surround suppression in the responses of primate SA1 and RA mechanoreceptive afferents mapped with a probe array.". Journal of neurophysiology 81 (6): 2711–9. PMID 10368391.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Craig, J. C.; Johnson (2000). "The two-point threshold: Not a measure of tactile spatial resolution.". Current Directions in Psychological Science 9: 29–32.