Tuscany

| Tuscany Toscana | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region of Italy | |||

| |||

| |||

| Country | Italy | ||

| Capital | Florence | ||

| Government | |||

| • President | Enrico Rossi (PD) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 22,993 km2 (8,878 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2012-10-30) | |||

| • Total | 3,679,027 | ||

| • Density | 160/km2 (410/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym | Tuscan | ||

| Citizenship[1] | |||

| • Italian | 90% | ||

| • Albanian | 1% | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| GDP/ Nominal | €106.1[2] billion (2008) | ||

| GDP per capita | €28,500[3] (2008) | ||

| NUTS Region | ITC | ||

| Website | www.regione.toscana.it | ||

Tuscany (Italian: Toscana, pronounced [tosˈkaːna]) is a region in central Italy with an area of about 23,000 square kilometres (8,900 sq mi) and a population of about 3.8 million inhabitants. The regional capital is Florence (Firenze).

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, traditions, history, artistic legacy and its influence on high culture. It is regarded as the birthplace of the Italian Renaissance and has been home to many figures influential in the history of art and science, and contain well-known museums such as the Uffizi and the Pitti Palace. Tuscany produces wines, including Chianti, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, Morellino di Scansano and Brunello di Montalcino. Having a strong linguistic and cultural identity, it is sometime considered "a nation within a nation". Seven Tuscan localities have been designated World Heritage Sites: the historic centre of Florence (1982); the historical centre of Siena (1995); the square of the Cathedral of Pisa (1987); the historical centre of San Gimignano (1990); the historical centre of Pienza (1996); the Val d'Orcia (2004), and Medici Villas and Gardens (2013). Tuscany has over 120 protected nature reserves, making Tuscany and its capital Florence a popular tourist destinations that attract millions of tourists every year.[4] (In 2007, the city became the world's 46th most visited city, with over 1.715 million arrivals).[5]

Geography

|

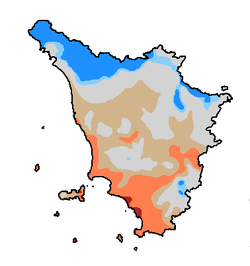

A: Im > 100

B: 80 < Im < 100

B1-B2: 20 < Im < 80

|

C2: 0 < Im < 20

C1: −33,3 < Im < 0

D: Im < −33,3 |

Roughly triangular in shape, Tuscany borders the regions of Liguria to the northwest, Emilia-Romagna to the north and east, Umbria to the east and Lazio to the southeast. The commune of Badia Tedalda, in the Tuscan Province of Arezzo, forms an enclave and exclave within Emilia-Romagna.

Tuscany has a western coastline on the Tyrrhenian Sea, containing the Tuscan Archipelago, of which the largest island is Elba. Tuscany has an area of approximately 22,993 square kilometres (8,878 sq mi). Surrounded and crossed by major mountain chains, and with few (but fertile) plains, the region has a relief that is dominated by hilly country used for agriculture. Hills make up nearly two-thirds (66.5%) of the region's total area, covering 15,292 square kilometres (5,904 sq mi), and mountains (of which the highest are the Apennines), a further 25% (—5,770 square kilometres (2,230 sq mi)). Plains occupy 8.4% of the total area 1,930 square kilometres (750 sq mi),—, mostly around the valley of the River Arno. Many of Tuscany's largest cities lie on the banks of the Arno, including the capital Florence, Empoli and Pisa.

The climate is fairly mild in the coastal areas, and is harsher and rainy in the interior, with considerable fluctuations in temperature between winter and summer,[6] giving the region a soil-building active freeze-thaw cycle in part accounting for the region's once having served as a key breadbasket of ancient Rome.[7]

History

Appennini and Villanovan cultures

The pre-Etruscan history of the area in the late Bronze and Iron Ages parallels that of the early Greeks.[8] The Tuscan area was inhabited by peoples of the so-called Apennine culture in the late second millennium BC (roughly 1350–1150 BC) who had trading relationships with the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations in the Aegean Sea.[8] Following this, the Villanovan culture (1100–700 BC) saw Tuscany, and the rest of Etruria, taken over by chiefdoms.[8] City-states developed in the late Villanovan (paralleling Greece and the Aegean) before "Orientalization" occurred and the Etruscan civilization rose.[8]

Etruscans

The Etruscans (Latin: Tusci) created the first major civilization in this region, large enough to establish a transport infrastructure, to implement agriculture and mining and to produce vibrant art.[9] The Etruscans lived in Etruria well into prehistory.[8] The civilization grew to fill the area between the Arno River and Tiber River from the 8th century BC, reaching its peak during the 7th and 6th centuries BC, finally succumbing to the Romans by the 1st century.[10] Throughout their existence, they lost territory (in Campania) to Magna Graecia, Carthage and Celts.[9] Despite being seen as distinct in its manners and customs by contemporary Greeks,[11] the cultures of Greece, and later Rome, influenced the civilization to a great extent. One reason for its eventual demise[10] was this increasing absorption by surrounding cultures, including the adoption of the Etruscan upper class by the Romans.[9]

Romans

Soon after absorbing Etruria, Rome established the cities of Lucca, Pisa, Siena, and Florence, endowed the area with new technologies and development, and ensured peace.[9] These developments included extensions of existing roads, introduction of aqueducts and sewers, and the construction of many buildings, both public and private. However, many of these structures have been destroyed by erosion due to weather.[9] The Roman civilization in the West collapsed in the 5th century and the region fell briefly to Goths to be re-conquered by the Byzantine Empire. In the years following 572 C.E., the Longobards arrived and designated Lucca the capital of their Duchy of Tuscia.[9]

The Medieval Period

Pilgrims travelling along the Via Francigena between Rome and France brought wealth and development during the medieval period.[9] The food and shelter required by these travellers fuelled the growth of communities around churches and taverns.[9] The conflict between the Guelphs and Ghibellines, factions supporting the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire in central and northern Italy during the 12th and 13th centuries, split the Tuscan people.[9] These two factors gave rise to several powerful and rich medieval communes in Tuscany: Arezzo, Florence, Lucca, Pisa, and Siena.[9] Balance between these communes was ensured by the assets they held; Pisa, a port; Siena, banking; and Lucca, banking and silk.[12] By the renaissance, however, Florence had become the cultural capital of Tuscany.[12] One family that benefitted from Florence's growing wealth and power was the ruling Medici Family. Lorenzo de' Medici was one of the most famous of the Medici and the legacy of this time is still visible today in the prodigious art and architecture in Florence. One of his famous descendants, Catherine de Medici, married Prince Henry (later King Henry II) of France in 1533.

The Black Death epidemic hit Tuscany starting in 1348.[13] It eventually killed 50% to 60% of Tuscans.[14][15] According to Melissa Snell, "Florence lost a third of its population in the first six months of the plague, and from 45% to 75% of its population in the first year."[16] In 1630, Florence and Tuscany were once again ravaged by the plague.[17]

The Renaissance

Tuscany, especially Florence, is regarded as the birthplace of the Renaissance. Though "Tuscany" remained a linguistic, cultural and geographic conception, rather than a political reality, in the 15th century, Florence extended its dominion in Tuscany through the annexation of Arezzo in 1384, the purchase of Pisa in 1405 and the suppression of a local resistance there (1406). Livorno was bought as well (1421).

From the leading city of Florence, the republic was from 1434 onward dominated by the increasingly monarchical Medici family. Initially, under Cosimo, Piero the Gouty, Lorenzo and Piero the Unfortunate, the forms of the republic were retained and the Medici ruled without a title, usually without even a formal office. These rulers presided over the Florentine Renaissance. There was a return to the republic from 1494 to 1512, when first Girolamo Savonarola then Piero Soderini oversaw the state. Cardinal Giovanni de' Medici retook the city with Spanish forces in 1512, before going to Rome to become Pope Leo X. Florence was dominated by a series of papal proxies until 1527 when the citizens declared the republic again, only to have it taken from them again in 1530 after a siege by an Imperial and Spanish army. At this point Pope Clement VII and Charles V appointed Alessandro de' Medici as the first formal hereditary ruler.

The Sienese commune was not incorporated into Tuscany until 1555, and during the 15th century Siena enjoyed a cultural 'Sienese Renaissance' with its own more conservative character. Lucca remained an independent Republic until 1847 when it became part of Grand Duchy of Tuscany by the will of its people. Piombino and other strategic towns constituted the tiny State of Presidi under Spanish control.

Modern Era

.svg.png)

In the 16th century, the Medicis, rulers of Florence, annexed the Republic of Siena, creating the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. The Medici family became extinct in 1737 with the death of Gian Gastone, and Tuscany was transferred to Francis, Duke of Lorraine and husband of Austrian Empress Maria Theresa, who let rule the country by his son. The dynasty of the Lorena ruled Tuscany until 1860, with the exception of the Napoleonic period, when most of the country was annexed to the French Empire. After the Second Italian War of Independence, a revolution evicted the last Grand Duke, and after a plebiscite Tuscany became part of the new Kingdom of Italy. From 1864 to 1870 Florence became the second capital of the kingdom.

Under Benito Mussolini, the area came under the dominance of local Fascist leaders as Dino Perrone Compagni (from Florence), and Costanzo and Galeazzo Ciano (from Leghorn). Following the fall of Mussolini and the armistice of 8 September 1943, Tuscany became part of the Nazi controlled Italian Social Republic, and was conquered almost totally by the Anglo-American during summer 1944. Following the end of the Social Republic, and the transition from the Kingdom to the modern Italian Republic, Tuscany once more flourished as a cultural center of Italy. After the establishment of regional autonomy in 1975, Tuscany has always been ruled by center-left governments.

Culture

Tuscany has an immense cultural and artistic heritage, expressed in the region's churches, palaces, art galleries, museums, villages and piazzas. Many of these artifacts are found in the main cities, such as Florence and Siena, but also in smaller villages scattered around the region, such as San Gimignano.

Art

Tuscany has a unique artistic legacy, and Florence is one of the world's most important water-color centres, even so that it is often nicknamed the "art palace of Italy" (the city is also believed to have the largest concentration of Renaissance art and architecture in the world).[18] Painters such as Cimabue and Giotto, the fathers of Italian painting, lived in Florence and Tuscany as well as Arnolfo and Andrea Pisano, renewers of architecture and sculpture; Brunelleschi, Donatello and Masaccio, forefathers of the Renaissance, Ghiberti and the Della Robbias, Filippo Lippi and Angelico; Botticelli, Paolo Uccello and the universal genius of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.[19][20]

The region contains numerous museums and art galleries, many housing some of the world's most precious works of art. Such museums include the Uffizi, which keeps Botticelli's Birth of Venus, the Pitti Palace, and the Bargello, to name a few. Most of the frescos, sculptures and paintings in Tuscany are held in the region's abundant churches and cathedrals, such as Florence Cathedral, Siena Cathedral, Pisa Cathedral and the Collegiata di San Gimignano.

Art Schools

In medieval period and in the Renaissance, there were four main Tuscan art schools which competed against each other: the Florentine School, the Sienese School, the Pisan School and the Lucchese School.

- The Florentine School refers to artists in, from or influenced by the naturalistic style developed in the 14th century, largely through the efforts of Giotto di Bondone, and in the 15th century the leading school of the world. Some of the best known artists of the Florentine School are Brunelleschi, Donatello, Michelangelo, Fra Angelico, Botticelli, Lippi, Masolino, and Masaccio.

- The Sienese School of painting flourished in Siena between the 13th and 15th centuries and for a time rivaled Florence, though it was more conservative, being inclined towards the decorative beauty and elegant grace of late Gothic art. Its most important representatives include Duccio, whose work shows Byzantine influence; his pupil Simone Martini; Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti; Domenico and Taddeo di Bartolo; Sassetta and Matteo di Giovanni. Unlike the naturalistic Florentine art, there is a mystical streak in Sienese art, characterized by a common focus on miraculous events, with less attention to proportions, distortions of time and place, and often dreamlike coloration. In the 16th century the Mannerists Beccafumi and Il Sodoma worked there. While Baldassare Peruzzi was born and trained in Siena, his major works and style reflect his long career in Rome. The economic and political decline of Siena by the 16th century, and its eventual subjugation by Florence, largely checked the development of Sienese painting, although it also meant that many Sienese works in churches and public buildings were not discarded or destroyed by new paintings or rebuilding. Siena remains a remarkably well-preserved Italian late-Medieval town.

- The Lucchese School, also known as the School of Lucca and as the Pisan-Lucchese School, was a school of painting and sculpture that flourished in the 11th and 12th centuries in the western and southern part of the region, with an important center in Volterra. The art is mostly anonymous. Although not as elegant or delicate as the Florentine School, Lucchese works are remarkable for their monumentality.

Main artistic centres

In the province of Arezzo:

In the province of Florence:

In the Province of Grosseto:

In the province of Livorno:

In the province of Lucca:

In the province of Massa and Carrara:

- Massa and Carrara

- Pontremoli

- Fivizzano

In the province of Pisa:

In the province of Prato:

In the province of Pistoia:

In the province of Siena:

Language

Apart from standard Italian, in Tuscany many varieties of 'Tuscan dialect' (dialetto toscano) are spoken.

Italian is in practice a "literary version" of Tuscan. It became the language of culture for all the people of Italy,[21] thanks to the prestige of the masterpieces of Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarca, Giovanni Boccaccio, Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini. It would later become the official language of all the Italian states and of the Kingdom of Italy, when it was formed.[22]

Music

Tuscany has a rich ancient and modern musical tradition, and has produced numerous composers and musicians, including Giacomo Puccini and Pietro Mascagni. Beyond Florence, the nine other provinces in the region of Tuscany, named for the largest city in, and capital of the province. Taken together, they offer a rich musical culture. Florence is the main musical centre of Tuscany. The city was at the heart of much of our entire Western musical tradition. It was there that the Florentine Camerata convened in the mid-16th century and experimented with setting tales of Greek mythology to music and staging the result: the first operas, fostering the further development of the operatic form, and the later developments of separate "classical" forms such as the symphony.

There are numerous musical centres in Tuscany. Arezzo is indelibly connected with the name of Guido d'Arezzo, the 11th-century monk who invented modern musical notation and the do-re-mi system of naming notes of the scale; Lucca hosted possibly the greatest Italian composer of Romanticism, Giacomo Puccini and Siena is well known for the Accademia Musicale Chigiana, an organization that currently sponsors major musical activities such as the Siena Music Week and the Alfredo Casella International Composition Competition. Other important musical centres in Tuscany include Lucca, Pisa and Grosseto.

Literature

Several famous writers and poets are from Tuscany, most notably Florentine author Dante. Tuscany's literary scene particularly thrived in the 13th century and the Renaissance.

In Tuscany, especially in the Middle Ages, popular love poetry existed. A school of imitators of the Sicilians was led by Dante da Majano, but its literary originality took another line — that of humorous and satirical poetry. The democratic form of government created a style of poetry which stood strongly against the medieval mystic and chivalrous style. Devout invocation of God or of a lady came from the cloister and the castle; in the streets of the cities everything that had gone before was treated with ridicule or biting sarcasm. Folgore da San Gimignano laughs when in his sonnets he tells a party of Sienese youths the occupations of every month in the year, or when he teaches a party of Florentine lads the pleasures of every day in the week. Cenne della Chitarra laughs when he parodies Folgore's sonnets. The sonnets of Rustico di Filippo are half-fun and half-satire, as is the work of Cecco Angiolieri of Siena, the oldest humorist we know, a far-off precursor of Rabelais and Montaigne.

Another type of poetry also began in Tuscany. Guittone d'Arezzo made art abandon chivalry and Provençal forms for national motives and Latin forms. He attempted political poetry, and although his work is often obscure, he prepared the way for the Bolognese school. Bologna was the city of science, and philosophical poetry appeared there. Guido Guinizelli was the poet after the new fashion of the art. In his work the ideas of chivalry are changed and enlarged. Only those whose heart is pure can be blessed with true love, regardless of class. He refuted the traditional credo of courtly love, for which love is a subtle philosophy only a few chosen knights and princesses could grasp. Love is blind to blasons but not to a good heart when it finds one: when it succeeds it is the result of the spiritual, not physical affinity between two souls. Guinizzelli's democratic view can be better understood in the light of the greater equality and freedom enjoyed by the city-states of the center-north and the rise of a middle class eager to legitimise itself in the eyes of the old nobility, still regarded with respect and admiration but in fact dispossessed of its political power. Guinizelli's Canzoni make up the bible of Dolce Stil Novo, and one in particular, "Al cor gentil" ("To a Kind Heart") is considered the manifesto of the new movement which will bloom in Florence under Cavalcanti, Dante and their followers. His poetry has some of the faults of the school of d'Arezzo. Nevertheless, he marks a great development in the history of Italian art, especially because of his close connection with Dante's lyric poetry.

In the 13th century, there were several major allegorical poems. One of these is by Brunetto Latini, who was a close friend of Dante. His Tesoretto is a short poem, in seven-syllable verses, rhyming in couplets, in which the author professes to be lost in a wilderness and to meet with a lady, who represents Nature, from whom he receives much instruction. We see here the vision, the allegory, the instruction with a moral object, three elements which we shall find again in the Divine Comedy. Francesco da Barberino, a learned lawyer who was secretary to bishops, a judge, and a notary, wrote two little allegorical poems, the Documenti d'amore and Del reggimento e dei costumi delle donne. The poems today are generally studied not as literature, but for historical context. A fourth allegorical work was the Intelligenza, which is sometimes attributed to Compagni, but is probably only a translation of French poems.

In the 15th century, humanist and publisher Aldus Manutius published Tuscan poets Petrarch and Dante Alighieri (The Divine Comedy), creating the model for what became a standard for modern Italian.

Cuisine

Simplicity is central to the Tuscan cuisine. Legumes, bread, cheese, vegetables, mushrooms and fresh fruit are used. Olive oil is made up of Moraiolo, Leccino, and Frantoiano olives. White truffles from San Miniato appear in October and November. Beef of the highest quality comes from the Chiana Valley, specifically a breed known as Chianina used for Florentine steak. Pork is also produced.[23]

Wine is a famous and common produce of Tuscany. Chianti is arguably the most well-known internationally. So many British tourists come to the area where Chianti wine is produced that this specific area has been nicknamed Chiantishire.

Postage stamps

Between 1851 and 1860, Grand Duchy of Tuscany, an independent Italian state until 1859 when it joined the United Provinces of Central Italy, produced two postage stamp issues which are among the most prized classic stamp issues of the world, and include the most valuable Italian stamp. The Grand Duchy of Tuscany was an independent Italian state from 1569 to 1859, but was occupied by France from 1808 to 1814. The Duchy comprised most of the present area of Tuscany, and its capital was Florence. In December 1859, the Grand Duchy officially ceased to exist, being joined to the Duchies of Modena and Parma to form the United Provinces of Central Italy, which was annexed by the Kingdom of Sardinia a few months later in March 1860. In 1862 it became part of Italy, and joined the Italian postal system.

Economy

Agriculture

The subsoil in Tuscany is relatively rich in mineral resources, with iron ore, copper, mercury and lignite mines, the famous soffioni (fumarole) at Larderello and the vast marble mines in Versilia. Although its share is falling all the time, agriculture still contributes to the region's economy. In the region's inland areas cereals, potatoes, olives and grapes (for the world-famous Chianti wines) are grown. The swamplands, which used to be marshy, now produce vegetables, rice, tobacco, beets and sunflowers.[6]

Industry

The industrial sector is dominated by mining, given the abundance of underground resources. Also of note are textiles, chemicals/pharmaceuticals, metalworking and steel, glass and ceramics, clothing and printing/publishing sectors. Smaller areas specialising in manufacturing and craft industries are found in the hinterland: the leather and footwear area in the south-west part of the province of Florence, the hot-house plant area in Pistoia, the ceramics and textile industries in the Prato area, scooters and motorcycles in Pontedera, and the processing of timber for the manufacture of wooden furniture in the Cascina area. The heavy industries (mining, steel and mechanical engineering) are concentrated along the coastal strip (Livorno and Pisa areas), where there are also important chemical industries. Also of note are the marble (Carrara area) and paper industries (Lucca area).[6]

Tourism

Many towns and cities in Tuscany have great natural and architectural beauty. There are many visitors throughout the year. As a result, the services and distribution activities, so important to the region's economy, are wide-ranging and well-organised.

An example of the services and distribution activities that have evolved in the Tuscan countryside are Agritourismos. Agritourism is a phenomenon developed in the Italian Countryside. The sustainability of Family Farms is achieved through the unique functions of Agritourism. It achieves environmental sustainability as well as financial and cultural sustainability, through funding from the government, traditional/organic agriculture techniques, traditional food preparation and the functions of a Bed and Breakfast/restaurant. As younger generations of farmers take over we can see the application of WWOOF volunteers, interns, educational outreach programs, and permaculture techniques. The potential for development of educational outreach in regards to the work and lifestyle of the family farm is high and important to the development of communities.

Fashion

The fashion and textile industry are the pillars of the Florentine economy. In the 15th century, Florentines were working with luxury textiles such as wool and silk. Today the greatest designers in Europe utilize the textile industry in Tuscany, and especially Florence.

Italy has one of the strongest textile industries in Europe, accounting for approximately one quarter of European production. Its turnover is over 25 billion euros. It is the third largest supplier of clothing after China and Japan. The Italian fashion industry generates 60% of its turnover abroad.[24]

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1861 | 1,920,000 | — |

| 1871 | 2,124,000 | +10.6% |

| 1881 | 2,187,000 | +3.0% |

| 1901 | 2,503,000 | +14.4% |

| 1911 | 2,670,000 | +6.7% |

| 1921 | 2,810,000 | +5.2% |

| 1931 | 2,914,000 | +3.7% |

| 1936 | 2,978,000 | +2.2% |

| 1951 | 3,159,000 | +6.1% |

| 1961 | 3,286,000 | +4.0% |

| 1971 | 3,473,000 | +5.7% |

| 1981 | 3,581,000 | +3.1% |

| 1991 | 3,530,000 | −1.4% |

| 2001 | 3,498,000 | −0.9% |

| 2011 | 3,750,000 | +7.2% |

| Source: ISTAT 2001 | ||

The population density of Tuscany, with 161 inhabitants per square kilometre (420 /sq mi) in 2008, is below the national average (198.8 /km2 or 515 /sq mi). This is due to the low population density of the provinces of Arezzo, Siena and primarily, Grosseto (50 /km2 or 130 /sq mi). The highest density is found in the province of Prato (675 /km2 or 1,750 /sq mi) followed by the provinces of Pistoia, Livorno, Florence and Lucca, peaking in the cities of Florence (more than 3,500 /km2 or 9,100 /sq mi), Livorno, Prato, Viareggio, Forte dei Marmi and Montecatini Terme (all with a population density of more than 1,000 /km2 or 2,600 /sq mi). The territorial distribution of the population is closely linked to the socio-cultural and, more recently, economic and industrial development of Tuscany.[6]

Accordingly, the least densely populated areas are those where the main activity is agriculture, unlike the others where, despite the presence of a number of large industrial complexes, the main activities are connected with tourism and associated services, alongside many small firms in the leather, glass, paper and clothing sectors.[6]

Italians make up 93% of the total population. Starting from the 1980s, the region attracted a large flux of immigrants, particularly from China. There is also a significant community of British and American residents. As of 2008, the Italian national institute of statistics ISTAT estimated that 275,149 foreign-born immigrants live in Tuscany, equal to 7% of the total regional population.

Government and politics

Tuscany is a stronghold of the center-left Democratic Party, forming with Emilia-Romagna, Umbria and Marche the famous Italian political "Red Quadrilateral". Since 1970, Tuscany has been continuously governed by the Socialist-Communist or PD-led governments. At the February 2013 elections, Tuscany gave more than 40% of its votes to Pierluigi Bersani, and only 20.7% to Silvio Berlusconi.[25]

Administrative divisions

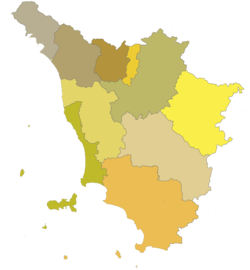

Tuscany is divided into ten provinces:

| Province | Area (km²) | Population | Density (inh./km²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Province of Arezzo | 3,232 | 345,547 | 106.9 |

| Province of Florence | 3,514 | 983,073 | 279.8 |

| Province of Grosseto | 4,504 | 225,142 | 50.0 |

| Province of Livorno | 1,218 | 340,387 | 279.4 |

| Province of Lucca | 1,773 | 389,495 | 219.7 |

| Province of Massa and Carrara | 1,157 | 203,449 | 175.8 |

| Province of Pisa | 2,448 | 409,251 | 167.2 |

| Province of Pistoia | 965 | 289,886 | 300.4 |

| Province of Prato | 365 | 246,307 | 674.8 |

| Province of Siena | 3,821 | 268,706 | 81.9 |

See also

- Cities and towns in Tuscany

- People from Tuscany

- Line of succession to the Tuscan throne

- Tuscan Archipelago

Footnotes

- ↑ "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT". Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ "Eurostat - Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". Epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- ↑ EUROPA - Press Releases - Regional GDP per inhabitant in 2008 GDP per inhabitant ranged from 28% of the EU27 average in Severozapaden in Bulgaria to 343% in Inner London

- ↑ Florence receives an average of 10 million tourists a year, making the city one of the most visited in the world.

- ↑ Caroline Bremner (11 Oct 2007). "Top 150 City Destinations: London Leads the Way". Euromonitor International. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "TOSCANA - Geography and history". Retrieved 9 March 2011. Text finalised in March 2004 - Eurostat.

- ↑ Military (Discovery network) Channel documentary series: "Rome: Power and Glory", episode title: "The Grasp of an Empire", copyright unknown, rebroadcast 11-12:00 hrs EDST, 2009-06-29.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Barker 2000, p. 5

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 Jones 2005, p. 2

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Barker 2000, p. 1

- ↑ Barker 2000, p. 4

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Jones 2005, p. 3

- ↑ Kohn, George C. (2008). Encyclopedia of plague and pestilence: from ancient times to the present. Infobase Publishing. p. 126. ISBN 0-8160-6935-2.

- ↑ Ole Jørgen Benedictow (2004). "The Black Death, 1346-1353: the complete history". Boydell & Brewer. p.303. ISBN 0-85115-943-5

- ↑ "The Economic Impact of the Black Death". EH.Net.

- ↑ Snell, Melissa (2006). "The Great Mortality". Historymedren.about.com. Retrieved 2009-04-19

- ↑ Cipolla, Carlo M. Fighting the Plague in Seventeenth Century Italy. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981.

- ↑ Miner, Jennifer (2008-09-02). "Florence Art Tours, Florence Museums, Florence Architecture". Travelguide.affordabletours.com. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ Art in Florence http://www.learner.org/interactives/renaissance/florence_sub2.html

- ↑ Renaissance Artists http://library.thinkquest.org/2838/artgal.htm

- ↑ "History of the Language | Italy". Lifeinitaly.com. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Tuscan dialect | English | Dictionary & Translation by Babylon". Babylon.com. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ Piras, 221-239.

- ↑

- ↑ 2013 Election report

References

- Barker, Graeme; Rasmussen, Tom (2000). The Etruscans. Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22038-0

- Jones, Emma (2005). Adventure Guide Tuscany & Umbria. Edison, NJ: Hunter. ISBN 1-58843-399-4

External links

| Find more about Tuscany at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| |

Definitions and translations from Wiktionary |

| |

Media from Commons |

| |

Quotations from Wikiquote |

| |

Source texts from Wikisource |

| |

Textbooks from Wikibooks |

| |

Learning resources from Wikiversity |

-

Tuscany travel guide from Wikivoyage

Tuscany travel guide from Wikivoyage - ©Official Tourism Site of Tuscany

- Official website of the Tuscany Region (in Italian)

- Official website of the Opera della Primaziale Pisana

- APUANEAT Typical Products & Resorts Tuscany guide

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)