Turnpike trusts

Turnpike trusts were bodies set up by individual acts of Parliament, with powers to collect road tolls for maintaining the principal roads in Britain from the 17th but especially during the 18th and 19th centuries. At the peak, in the 1830s, over 1,000 trusts[1] administered around 30,000 miles (48,000 km) of turnpike road in England and Wales, taking tolls at almost 8,000 toll-gates and side-bars.[2]

During the early 19th century the concept of the turnpike trust was adopted and adapted to manage roads within the British Empire (Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and South Africa) and in the USA.[2]

Turnpikes declined with the coming of the railways and then the Local Government Act of 1888 gave responsibility for maintaining main roads to county councils and county borough councils.

Etymology

The term "turnpike" originates from the similarity of the gate used to control access to the road, to the barriers once used to defend against attack by cavalry. The turnpike consisted of a row of pikes or bars, each sharpened at one end, and attached to horizontal members which were secured at one end to an upright pole or axle, which could be rotated to open or close the gate.[3]

Precursors to turnpike trusts

Pavage grants, originally made for paving the marketplace or streets of towns, began also to be used for maintaining some roads between towns in the 14th century. These grants were made by letters patent, almost invariably for a limited term, presumably the time likely to be required to pay for the required works.

Tudor statutes had placed responsibility on each parish to maintain all its roads. This arrangement was adequate for roads that the parishioners used themselves but proved unsatisfactory for the principal highways that were used by long-distance travellers and waggoners.[4] During the late 17th century, the piecemeal approach to road maintenance caused acute problems on the main routes into London. As trade increased, the growing numbers of heavy carts and carriages led to serious deterioration in the state of these roads and this could not be remedied by the use of parish statute labour. A Parliamentary Bill, presented in 1621/2, proposed to relieve the parishes responsible for part of the Great North Road by imposing a scale of tolls on various sorts of traffic. The revenue from the tolls was to be employed in repairing the road, however, the Bill was defeated. During the following forty years, the idea of making travellers contribute to the repair of roads was raised on several occasions.[5]

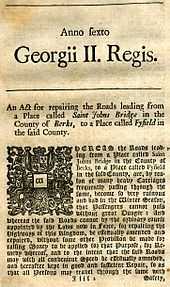

Many parishes continued to struggle to find funds, to repair major roads and in Hertfordshire several parishes were persistently presented at Quarter Sessions for their failure to keep the Old North Road in a good state of repair. Then in 1656 the parish of Radwell, Hertfordshire petitioned the Quarter Sessions for help to maintain their section of the Great North Road. Probably as a result of this petition the Quarter Session Justices of Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire represented the matter to parliament.[6] Parliament passed an act that gave the local justices powers to erect toll-gates on a section of the Great North Road, between Wadesmill, Hertfordshire; Caxton, Cambridgeshire; and Stilton, Huntingdonshire for a period of eleven years and the revenues so raised should be used for the maintenance of the Great North Road in their juristrictions.[6][7][5] The toll-gate erected at Wadesmill became the first effective toll-gate in England. Parliament then gave similar powers to the justices in other counties in England and Wales.[6] An example being the first Turnpike Act for Surrey that in 1696, during the reign of William III, provided for the repair of the highway between Reigate in Surrey and Crawley in Sussex.[8] The act made provision to erect turnpikes, and appoint toll collectors; also to appoint surveyors, who were authorized by order of the Justices to borrow money at 5 per cent, on security of the tolls.[8]

The first turnpike trusts

The first scheme that had trustees who were not justices was established through a Turnpike Act in 1707, for a section of the London-Chester road between Fornhill and Stony Stratford. The basic principle was that the trustees would manage resources from the several parishes through which the highway passed, augment this with tolls from users from outside the parishes and apply the whole to the maintenance of the main highway. This became the pattern for the turnpiking of a growing number of highways, sought by those who wished to improve flow of commerce through their part of a county. [6]

The proposal to turnpike a particular section of road was normally a local initiative and a separate Act of Parliament was required to create each trust. The Act gave the trustees responsibility for maintaining a specified part of the existing highway. It provided them with powers to achieve this; the right to collect tolls from those using the road was particularly important. Local gentlemen, clergy and merchants were nominated as trustees and they appointed a clerk, a treasurer and a surveyor to actually administer and maintain the highway. These officers were paid by the trust. Trustees were not paid, though they derived indirect benefits from the better transport, which improved access to markets and led to increases in rental income and trade.[9]

The first action of a new trust was to erect turnpike gates at which a fixed toll was charged. The Act gave a maximum toll allowable for each class of vehicle or animal - for instance one shilling and six pence for a coach pulled by four horses, a penny for an unladen horse and ten pence for a drove of 20 cows. The trustees could call on a portion of the statute duty from the parishes, either as labour or by a cash payment. The trust applied the income to pay for labour and materials to maintain the road. They were also able to mortgage future tolls to raise loans for new structures and for more substantial improvements to the existing highway. [9]

The trusts applied some funds to erecting tollhouses that accommodated the pikeman or toll-collector beside the turnpike gate. Although trusts initially organised the collection of tolls directly, it became common for them to auction a lease to collect tolls. Specialist toll-farmers would make a fixed payment to the trust for the lease and then organise the day-to-day collection of the money, leaving themselves with a profit on their operations over a year.[9]

The powers of a trust were limited, normally to 21 years, after which it was assumed that the responsibility for the now-improved road would be handed back to the parishes. However, trusts routinely sought new powers before this time limit, usually citing the need to pay off the debts incurred in repairing damage caused by a rising volume of traffic, or in building new sections of road.[9]

The growth of the turnpike system

During the first three decades of the 18th century, sections of the main radial roads into London were put under the control of individual turnpike trusts. The pace at which new turnpikes were created picked up in the 1750s as trusts were formed to maintain the cross-routes between the Great Roads radiating from London. Roads leading into some provincial towns, particularly in Western England, were put under single trusts and key roads in Wales were turnpiked. In South Wales, the roads of complete counties were put under single turnpike trusts in the 1760s. A further surge of trust formation occurred in the 1770s, with the turnpiking of subsidiary connecting roads, routes over new bridges, new routes in the growing industrial areas and roads in Scotland. About 150 trusts were established by 1750; by 1772 a further 400 were established and, in 1800, there were over 700 trusts.[10] In 1825 about 1,000 trusts controlled 18,000 miles (29,000 km) of road in England and Wales.[11]

The Acts for these new trusts and the renewal Acts for the earlier trusts incorporated a growing list of powers and responsibilities. From the 1750s, Acts required trusts to erect milestones indicating the distance between the main towns on the road. Users of the road were obliged to follow what were to become rules of the road, such as driving on the left and not damaging the road surface. Trusts could take additional tolls during the summer to pay for watering the road in order to lay the dust thrown up by fast-moving vehicles. Parliament also passed a few general Turnpike Acts dealing with the administration of the trusts and restrictions on the width of wheels - narrow wheels were said to cause a disproportionate amount of damage to the road.

The rate at which new trusts were created slowed in the early 19th century but the existing trusts were making major investments in highway improvement. The government had been directly involved in the building of military roads in Scotland following a rebellion in 1745, but the first national initiative was a scheme to aid communications with Ireland. Between 1815 and 1826 Thomas Telford undertook a major reorganization of the existing trusts along the London to Holyhead Road, and the construction of large sections of new road to avoid hindrances, particularly in North Wales.

By 1838 the turnpike trusts in England were collecting £1.5 million p.a. from leasing the collection of tolls but had a cumulative debt of £7 million, mainly as mortgages.[12] Even at its greatest extent, the turnpike system only administered a fifth of the roads in Britain; the majority being maintained by the parishes. A trust would typically be responsible for about 20 miles (32 km) of highway, although exceptions such as the Exeter Turnpike Trust controlled 147 miles (237 km) of roads radiating from the city. On the Bath Road for instance, a traveller from London to the head of the Thames Valley in Wiltshire would pass through the jurisdiction of seven trusts, paying a toll at the gates of each. Although a few trusts built new bridges (e.g. at Shillingford over the Thames), most bridges remained a county responsibility. A few bridges were built with private funds and tolls taken at these (e.g., the present Swinford Toll Bridge over the Thames).

Operation of turnpike trusts

Quality

The quality of early turnpike roads was varied.[13] Although turnpiking did result in some improvement to each highway, the technologies used to deal with geological features, drainage, and the effects of weather, were all in their infancy. Road construction improved slowly, initially through the efforts of individual surveyors such as John Metcalf in Yorkshire in the 1760s. 19th-century engineers made great advances, notably Thomas Telford and John Loudon McAdam. [14]

The engineering work of Telford on the Holyhead Road (now the A5) in the 1820s reduced the journey time of the London mail coach from 45 hours to just 27 hours, and the best mail coach speeds rose from 5-6 mph (8–10 km/h) to 9-10 mph (14–16 km/h). McAdam and his sons were employed as general surveyors (consultant engineers) to many of the main turnpike trusts in southern England. They recommended the building of new sections of road to avoid obstructions, eased steep slopes and directed the relaying of existing road-beds with carefully graded stones to create a dry, fast-running surface (known as Macadamising). Coach design improved to take advantage of these better roads and in 1843 the London-to-Exeter mail coach could complete the 170-mile (270-km) journey in 17 hours.

Social impact

The introduction of toll gates had been resented by local communities which had freely used the routes for centuries. Early Acts had given magistrates powers to punish anyone damaging turnpike property, such as defacing milestones, breaking turnpike gates or avoiding tolls. Opposition was particularly intense in mountainous regions where good routes were scarce. In Mid Wales in 1839, new tolls on old roads sparked protests known as the Rebecca Riots. There were sporadic outbursts of vandalism and violent confrontation by gangs of 50 to 100 or more local men, and gatekeepers were told that if they resisted they would be killed. In 1844, the ringleaders were caught and transported to Australia as convicts.[15] However, the result was that toll gates were dismantled and the trusts abolished in the six counties of South Wales, their powers being transferred to a roads board for each county.[16]

The end of the system

By the early Victorian period toll gates were perceived as an impediment to free trade. The multitude of small trusts were frequently charged with being inefficient in use of resources and potentially suffered from petty corruption.

The railway era spelt disaster for most turnpike trusts. Although some trusts in districts not served by railways managed to increase revenue, most did not. In 1829, the year before the Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened, the Warrington and Lower Irlam Trust had receipts of £1,680 but, by 1834, this had fallen to £332. The Bolton and Blackburn Trust had an income of £3,998 in 1846, but in 1847 following the completion of a railway between the two towns, this had fallen to £3,077 and, in 1849, £1,185.[17]

The debts of many trusts became significant; forced mergers of solvent and debt-laden trusts became frequent, and by the 1870s it was feasible for Parliament to close the trusts progressively without leaving an unacceptable financial burden on local communities. From 1871, all applications for renewal were sent to a Turnpike Trust Commission. This arranged for existing Acts to continue, but with the objective of discharging the debt, and returning the roads to local administration, which was by then by highway boards. The Local Government Act of 1888 gave responsibility for maintaining main roads to county councils and county borough councils. When a trust was ended, there were often great celebrations as the gates were thrown open. The assets of the trust, such as tollhouses, gates and sections of surplus land beside the road were auctioned off to reduce the debt, and mortgagees were paid at whatever rate in the pound the funds would allow.

The legacy of the turnpike trust is the network of roads that still form the framework of the main road system in Britain. In addition, many roadside features such as milestones and tollhouses have survived,[18] despite no longer having any function in the modern road management system.

Gallery

-

The surviving Copper Castle Tollhouse on the Honiton Turnpike.

-

A surviving milestone at Beedon on the Chilton Pond to Newtown River Turnpike.

-

Milepost on the Keighley and Kendal Turnpike at Gargrave: Settle 10 3/4, Kendal 40, Skipton 4 ¾ and Keighley 14 miles.

See also

- Toll roads in Great Britain — for a wider perspective on preceding and succeeding arrangements

- Table of English Turnpikes Turnpikes.org.uk, Alan Rosevear, Sept 2010. Accessed July 2011

- Table of turnpike trusts in Ireland, University of Southampton Library, Accessed July 2011

- Sparrows Herne turnpike — The London — Aylesbury turnpike road.

- Sheffield to Hathersage Turnpike

- Turnpike trusts in Greater Manchester — Describes the trusts which operated within Greater Manchester, from the 0.5 miles (800 m) long Little Lever Trust to the 22 miles (35 km) Manchester to Saltersbrook Trust.

- Keighley and Kendal Road - The Turnpike through Craven, Yorkshire.

Further reading

General publications

- Albert, W (1972). The Turnpike Road System in England 1663–1840. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-03391-8.

- Copeland, J (1968). Roads and their Traffic, 1750–1850. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4219-3.

- Wright, G.N. (1992). Turnpike Roads. Shire Publications Ltd. ISBN 0-7478-0155-X.

Local publications

- Cossons, A. (1994). Coaching Days – The Turnpike Roads of Nottinghamshire. Nottingham: Nottinghamshire County Council Leisure Services.

- Cossons, A. (2003). The Turnpike Roads of Leicestershire & Rutland. Leicester: Kairos Press.

- Freethy, R. (1986). Turnpikes & Tollhouses in Lancashire. privately published.

- Gloucester Record Office (1976). Gloucester Turnpike Roads. Gloucester Record Office.

- Hurley, H. (1992). The Old Roads of South Herefordshire - Trackway to Turnpike. The Pound House.

- Jenkinson, T. (August 2011). "Turnpikes and Toll-collectors". Family Tree Magazine.

- Jenkinson, T.; Taylor, P. (2010). The Toll-houses of North Devon. Polystar Press. ISBN 978-1-907154-03-4.

- Jenkinson, T; Taylor, P. (2009). The Toll-houses of South Devon. Polystar Press. ISBN 978-1-907154-01-0.

- Morley, F. (1961). The Great North Road - A Journey in History. London: Macmillan.

- Phillips, D. (1983). The Great Road to Bath. Countryside Books.

- Quatermaine, J.; Trinder, B.; Turner, R. (2003). Thomas Telford’s Holyhead Road. Report 135. Council for British Archaeology.

- Rosevear, A. (1995). Roads in the Upper Thames Valley. privately published.

- Smith, H. (2003). The Sheffield and Chesterfield to Derby Roads. Sheffield: privately published. ISBN 0-9521541-5-3.

- Taylor, W. (1996). The Military Roads in Scotland. Argyll: House of Lochar.

- Viner, D. (2007). Roads Tracks and Turnpikes. The Discover Dorset series. Wimborne: Dovecote Press.

- Williams, L.A. (1975). Road Transport in Cumbria in the nineteenth century. London: George Allen & Unwin.

References

- Notes

- ↑ Parliamentary Papers, 1840, Vol 280 xxvii.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Searle 1930, p. 798.

- ↑ Tupling 1952, p. 3.

- ↑ Pawson 1977, p. 70–71.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Records of Turnpike Trusts National Archive. Accessdate 6 December 2012

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Webb. English Local Government. pp. 157-159

- ↑ Statute, 15 Car. II, c.1.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Turnpike Trusts: County Reports of the Secretary. p. 4.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Webb. English Local Government. pp. 159-165

- ↑ Pawson 1977, pp. 341, 260.

- ↑ Hampshire Maps University of Portsmouth. Accessdate 6 December 2012

- ↑ Parliamentary Papers, 1840, Vol 289

- ↑ Parliamentary Papers, 1840, Vol 256 xxvii.

- ↑ The Turnpike Trust Schools History.org, Accessed July 2011

- ↑ The Rebecca Riots Powys Digital History Project

- ↑ Riden 1987, p. 139.

- ↑ Tupling 1952, p. 18.

- ↑ "Turnpike roads in England". Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- Bibliography

- Pawson, E. (1977), Transport and Economy: the turnpike roads of eighteenth century England

- Riden, Philip (1987), Record Sources for Local History, B. T. Batsford Ltd, ISBN 0-7134-4726-5

- Secretary of State (1852), Turnpike Trusts: County Reports of the Secretary of State: Number 2. Surrey. in Accounts and Papers: Turnpike Roads:Volume XLIV, London: HM Stationery Office, retrieved 14 July 2011

- Searle, M. (1930), Turnpikes and Toll Bars, Limited Edition, Hutchinson & co.

- Tupling, G. H. (1952), The Turnpike Trusts of Lancashire 94, Manchester Central Library, Local Studies: Memoirs and Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, session 1952-1953

- Webb, Sidney; Webb, Beatrice (1922). English local Government: Statutory Authorities for Special Purpose. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Further reading

- Ward, M & A (2011), The Toll House, Medlar Press., ISBN 978-1-907110-18-4

External links

- British Tollhouses has photos and maps of surviving British tollhouses

- for links to material on English turnpikes

- Timeline of British Turnpike Trusts University of Portsmouth, Department of Geography

- Key dates in Road Building Thepotteries.org

- Tollgates of London Georgian Index