Turkish carpet

Turkish carpets and rugs, whether hand knotted or flat woven (Kilim, Soumak, Cicim, Zili), are among the most well known and established hand crafted art works in the world.[1] Historically: religious, cultural, environmental, sociopolitical and socioeconomic conditions created widespread utilitarian need and have provided artistic inspiration among the many tribal peoples and ethnic groups in Central Asia and Turkey.[2] The term tends to cover not just the products of the modern territory of Turkey, but also those of Turkic peoples living elsewhere, mostly to the east of Anatolia.

Apparently originating in the traditions of largely nomadic Turkic peoples, the Turkish carpet, like the Persian carpet, developed during the medieval Seljuk period a more sophisticated urban aspect, produced in large workshops for commissions by the court and for export. The many styles of design reached maturity during the early Ottoman Empire, and most modern production, especially for export, looks back to the styles of that period. Turkish (also known as Anatolian) rugs and carpets are made in a wide range of distinct styles originating from various regions in Anatolia. Important differentiators between these styles may include: the materials, construction method, patterns and motif, geography, cultural identity and intended use.

History

The oldest records of flat woven kilims come from Çatalhöyük Neolithic pottery, circa 7000 BC. One of the oldest settlements ever to have been discovered, Çatalhöyük is located south east of Konya in the middle of the Anatolian region.[3] The excavations to date (only 3% of the town) not only found carbonized fabric but also fragments of kilims painted on the walls of some of the dwellings. The majority of them represent geometric and stylized forms that are similar or identical to other historical and contemporary designs.[4]

The oldest known hand knotted rug is the famous so-called Pazyryk Carpet, dating back to the 5th century BC. It was excavated by Russian Professor Sergei Rudenko and his archeology team, from the Pazyryk burials, a Scythian burial mound in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, near the tri- border area of modern day Russia, Mongolia and China, in the late 1940s.[5] 5400 feet above sea level, the rug, along with other textiles and artifacts, was preserved in ice probably due to the common belief that bandits had robbed the grave site soon after the burial, thus allowing water to enter and eventually freeze over the next 2500 years. The origins of the Pazyryk Carpet are still a matter of scholastic debate.[6][7][8] However, the general consensus of scholars and historians hold that the art and practice of rug weaving originate from Central Asia.[9]

The populace of Anatolia through the ages have included many great ancient civilizations, such as the Hittites, the Phrygians, the Assyrians, the Ancient Persians, the Ancient Greeks, and the early Byzantine Empire (Roman Emperor Constantine the Great's Eastern Christian Capital). Later the Seljuks and the Ottoman Empire. There are documentary records of carpets being used by the ancient Greeks and Persians, but we have little idea of what such carpets were like. The knotted rug is believed to have reached Asia Minor and the Middle East with the expansion of various nomadic tribes peoples during the latter period of the great Turkic migration of the 8th and 9th centuries.

Very little is then known about the history of rugs until the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries from which Seljuk examples found in various Turkish mosques have survived, nearly all now in museums or private collections.[10]

Right File: Konya 18th-century carpet with Memling gul design.

In 1272, the Venetian merchant traveler and explorer Marco Polo was the first European writer to mention Anatolian carpets, specifically mentioning the "Beautiful rugs of Konya and Karaman".[12] Konya carpets are named for the region in which they were made. Renamed from the Greek Iconium when the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum made it their capital, Konya is one of the largest and oldest continuously occupied cities in Asia Minor. When Polo wrote of the Konyas, he had probably seen them in manufactories that were attached to the Seljuk courts. In the early 20th century, large carpets were found in the Alâeddin Mosque in Konya. They are now housed in the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum in Istanbul.

Famously depicted in European paintings of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, beautiful Anatolian rugs were often used from then until modern times, to indicate the high economic and social status of the owner. Among other names, some of these rugs have come to be known as "Lotto carpets", "Holbein carpets", and "Memling" or "Memling gul carpets". These terms make reference to their depiction in minute detail in paintings by Lorenzo Lotto, Hans Holbein the Younger and Hans Memling.[13] In addition, there are a great number of other known and unknown artists who also represent Anatolian carpets of the Seljuk Empire era in their paintings.[14]

Seljuk carpets can be characterized by geometric and stylized floriated motifs called guls in repeating rows and by Kufic syle inscription border patterns. By the beginning of the 14th century, less stylized large animal figures emerged in Turkish rugs. By the 16th century, the medallion motifs and the diverse foliate compositions had taken over, as the influences of the expanding Ottoman territories and Persian and Mamluk arts were felt. This period claims two major groups of rugs; Usak rugs with the motif of one or more very large medallions and Ottoman Court rugs with naturalistic motifs. Ottoman Court rugs utilized the Iranian senneh knot, in order to accommodate the very fine and detailed floral designs and the clusters of Turkish flowers – the tulip, hyacinth, carnation, rose, and the blossoming branches.

The modern history of carpets and rugs began in the 19th century when large cottage industry and workshop productions flourished in Iran, Azerbaijan and Central Asia in order to meet the ever increasing demand for handmade carpets on the International market.

The geographical regions where inhabitants have lived throughout the centuries lie in the temperate zone. Temperature fluctuations between day and night, summer and winter may vary greatly. Turks; nomadic or pastoral, agrarian or town dwellers, living in tents or in sumptuous houses in large cities, have protected themselves from the extremes of the cold weather by covering the floors, and sometimes walls and doorways, with carpets and rugs. The carpets are always hand made of wool or sometimes cotton, with occasional additions of silk. These carpets are natural barriers against the cold. Turkish pile rugs and kilims are also frequently used as tent decorations, grain bags, camel and donkey bags, ground cushions, oven covers, sofa covers, bed and cushion covers, blankets, curtains, eating blankets, table top spreads, prayer rugs, and for ceremonial occasions.

The Kurds, Yörük, Yahyali, Turkomen and other tribal groups throughout Turkey continue to weave much sought after rugs. Eastern and Central Turkey in particular, weaving a great number of nomadic pieces for the market and for personal use.[15]

Turkish rugs are fairly distinguishable amidst carpets from other major weaving groups, such as Persian or Caucasian carpets. Aside from the classic double knot, their color scheme and design features are mostly recognizable, albeit, there are numerous variations province to province. From the faded palette and elegance of an Uşak carpet, to the bold colorful design motifs of an Eastern Anatolian nomadic piece, Turkish carpets have maintained their distinct identities reflecting an equally strong, diverse and colorful nation.

In general, the Turkish take their shoes off upon entering a house. Thus, the dust and dirt of the outdoors are not tracked inside. The floor coverings remain clean and the inhabitants of the house, if need be, can comfortably rest on the floor. In traditional households, women and girls take up carpet and kilim weaving as a hobby as well as a means of earning money. Women learn their weaving skills at an early age, taking months or even years to complete the beautiful pile rugs and flat woven kilims that were created for their use in every aspect of daily life. As is true in most weaving cultures, traditionally and nearly exclusively, it is women and girls who are both artisan and weaver.[16][17]

Selçuk (Seljuk) Carpets

A high point in the art of carpet making was achieved during the three centuries of the Seljuk Period, but unfortunately there are no surviving examples from the period called the "Great Seljuq Empire", 1037–1194. There are however, surviving carpets and fragments from the "Anatolian Seljuk Period", 1243–1302. These pieces have been designated as the "Konya Carpets", however, this is a misnomer. The sources of the evidence come from three finds: those from Konya, those from Beyşehir and those from Fostat.

In spite of the fragmented condition of most of these samples, it has been possible to piece together what is believed to be, the first expression in a consistent development of design and quality. Thus this group can be called the first group of Turkish carpets, recognizable as the forerunners of carpets of later periods, even up to the present.

Today the total Seljuk carpet collection consists of eighteen pieces, fifteen of which are fragments. Eight of these were found in Konya, three in Beyşehir, and seven are from Fostat. Only two within the group are quite similar, both of which are now in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts in Istanbul. The others, all having varying colors and motifs, are completely unique. Such variations indicate the existence of considerable creative potential on the parts of those who produced them.

In essence, a study of the Seljuk group reveals that the prototypic designs were derived from the infusion of highly stylized floral motifs into geometric designs, and from border compositions consisting of Kufic patterns. In some cases, the geometric forms are created by the repetition of motifs in rows. Floral motifs, if one can identify them as such, are not only stylized but highly abstract, certainly representational figures are unknown. A thorough examination of each of these fragments may well reveal that generalizations must give way to the unique and stunning quality of each piece.

The original carpets discovered in Konya's Alaeddin Mosque dating from the first half of the 13th century are products of Seljuk Anatolia and show the development in pile carpet weaving up to that period. They have also come to be considered by some experts, prototypes, for all post-Seljuk carpets. The details of their origins are still a matter of speculation.[18][19]

Ottoman Court Carpets

.jpg)

A weaving workshop was established in 1843 in Hereke, a small coastal town 60 kilometers from Istanbul on the bay of Izmit.[20] It also supplied the royal palaces with silk brocades and other textiles. Known as the Hereke Imperial Factory, the mill was subsequently enlarged to include looms producing cotton fabric. Silk brocades and velvets for drapes and upholstery were manufactured at a workshop known as the "kamhane". In 1850 the cotton looms were moved to a factory in Bakirköy, west of Istanbul, and one hundred jacquard looms were installed in Hereke. Although in the early years the factory produced exclusively for the Ottoman palaces, as production increased the woven products were available in the Kapalıçarşı or Grand Bazaar, in the second half of the 19th century. In 1878 a fire in the factory caused extensive damage, and it was not reopened until 1882. Carpet production began in Hereke in 1891 and expert carpet weavers were brought from the famous carpet weaving centers of Sivas, Manisa and Ladik. The carpets were all hand woven, and in the early years they were either made for the Ottoman palaces or as gifts for visiting statesmen. The number of looms steadily increased to meet the demand and, when Hereke carpets went on sale in Istanbul, their fame quickly spread to Europe. Soon the Hereke factory was receiving many commercial orders and business flourished.

Hereke carpets are known primarily for their fine weave. Silk thread or fine wool yarn and occasionally gold, silver and cotton thread are used in their production. Wool carpets produced for the palace had 60–65 knots per square centimeter, while silk carpets had 80–100 knots.

The oldest Hereke carpets, now exhibited in Topkapı and other palaces in Istanbul, contain a wide variety of colours and designs. The typical "palace carpet" features intricate floral designs, including the tulip, daisy, carnation, crocus, rose, lilac, and hyacinth. It often has quarter medallions in the corners. The medallion composition used in rugs made in Usak, in western Turkey, since the 16th century was widely used at the Hereke factory. These medallions are curved on the horizontal axis and taper to points on the vertical axis. Hereke prayer rugs feature patterns of geometric motifs, tendrils and lamps as background designs within the representation of a mihrab (prayer niche). Once referring solely to carpets woven at Hereke, the term "Hereke carpet" now refers to any high quality carpet woven using similar techniques. Hereke carpets remain among the finest and most valuable examples of woven carpets in the world.[21]

Construction method

A variety of tools are needed in the construction of a handmade rug. Some tools, such as a loom, are an absolute necessity for all weavers, and other tools, such as a hook, are used only by certain weaving groups. In general, different rug weaving areas use slightly different versions of the same tools. Some common tools used in rug weaving are: vertical looms, horizontal looms, floor looms, design plates, knives, scissors, spindles, hooks and combs.[22]

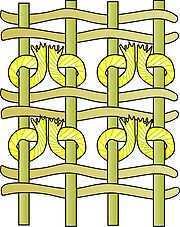

Most pile rugs from Anatolia utilize the symmetrical ghiordes double knot or "Turkish knot". Each knot is made on two warps. With this form of knotting, each end of the pile thread is wrapped all the way around the two warps, pulled down and cut, creating a stronger rug than the much more typical asymmetrical single knot senneh or "Persian knot".

The Seljuk rugs found at Konya, capital of Anatolian Seljuks, are knotted with the Turkish ghiordes knot, in the same style as the carpet fragments found by Rudenko and his team during the Pazyryk excavations in the Altai mountains. Ottoman court rug designers also started the use of silk in the warp and weft on looms in Constantinople (Istanbul) and Bursa. After each row is woven, a length of yarn is passed through it and this single-warp knot creates the denser knotting which permits finer and more intricate designs to be created. In some of the carpets, a relief effect is obtained by clipping the pile unevenly.

In 1891, the first carpet factory with 100 looms was opened by Abdulhamid II at Hereke and even today, rugs in Anatolia, especially around Kayseri, Sivas, Konya, Kars, and Isparta, follow the traditional patterns of this truly Turkish art.[23]

Materials

Only natural fibers are used in handmade rugs. The most common materials used for the pile are wool, silk and cotton. Sometimes, goat and camel hair are also used by nomadic and village weavers.

Wool is the most frequently used pile material in a handmade rug because it is soft, durable, easy to work with and not too expensive. This combination of characteristics is not found in other natural fibers. Wool comes from the coats of sheep. Natural wool comes in colors of white, brown, fawn, yellow and gray, which are sometimes used directly without going through a dyeing process.

Cotton is used primarily in the foundation of rugs. However, some weaving groups such as Turkomans also use cotton for weaving small white details into the rug in order to create contrast.

Wool on wool (wool pile on wool warp and weft): This is the most traditional and often the most "authentic" (if such a word can be used) type of Anatolian rug. Wool on wool carpet weaving dates back further and utilizes more traditional design motifs than its counterparts. Because wool cannot be spun extra finely, the knot count is often not as high as a "wool on cotton" or "silk on silk" rug. Wool on wool carpets tend to be more tribal or nomadic using traditional geometric designs or otherwise non-intricate patterns.

Wool on cotton (wool pile on cotton warp and weft): This particular combination facilitates a more intricate design pattern than a "wool on wool carpet", as cotton can be finely spun which allows for a higher knot count. A "wool on cotton" rug is often indicative of a so-called, "city rug". Wool on cotton rugs feature floral designs and flourishes in addition to traditional geometric patterns.

Silk on silk (silk pile on silk warp and weft): This is perhaps the most intricate type of carpet; featuring a very fine weave. Knot counts on some superior quality "silk on silk" rugs can be as high as 28×28 knots/cm2. Knot counts for silk carpets intended for floor coverings should be no greater than 100 knots per square cm, or 10×10 knots/cm2. Carpets woven with a knot count greater than 10×10 knots/cm2 should only be used as a wall or pillow tapestry. These very fine, intricately woven rugs and carpets are usually no larger than 3×3 m.

Carpets by regions

Rugs have been woven in Anatolia since before the 13th century. Carpets derive their names from the localities in which they are produced, tribal groups they are associated with, as well as from the techniques of their manufacture, the characteristic patterns of their ornamentation, the layout of the design and the intention of their use.

The motifs employed in Turkish carpets are so varied and can be classified into so many subcategories that they constitute, as it were, a great fan stretching from Thrace to Kars. From the Sivas region emerge the Sarkisla, Zara, Kangal and Divrigi carpets characterised by a remarkable wealth of symbolic expression forming one of the links in the rich chain of Turkish tradition. Motifs differing markedly in form and detail can be found in Anatolian kilims from Yagcibekir to Dosemealti, from Kula to Çanakkale.

The most important distinguishing feature of the motifs employed in Anatolian carpets is the "symbolisation" imposed by the traditional weaving techniques. The linear values of these woven fabrics constitute the symbolic representation of the ideas which the Turkish woman wishes to express. Perhaps it would be an exaggeration to say that all the motifs employed in carpets and kilims bear a symbolic significance, but it is usually possible to find a hidden connection between the "visible motif" and the "under lying motif". The symbolic values conferred upon the objects are stylised by the Turkish weaving technique itself. The language of the motifs is the language of any-one who can understand.[24]

Well known weaving cities, towns, and districts include (but are not limited to): Uşak, Bergama, Milas, Hereke, Konya, Nevşehir, Nigde, Antalya, Çanakkale, Kars, Kayseri, Malatya, Siirt, Taşpınar, Sivas, Yahyali, Izmir, Gaziantep Manisa, Ladik and the Van Province.

Gallery

-

Central Anatolian rug shop. Owner and son display rare antique Anatolian Yatak

-

Antique Anatolian Kurdish Yastik

-

Anatolian carpet with double medallion, late 16th century

-

Kirşehir praying rug. 18th century. Mevlâna Mausoleum. Konya

-

Edirne Selimiye Mosque interior and prayer rug Saph

-

Early 20th-century Siirt Battaniyesi. Child's mohair prayer rug/blanket

-

Nomadic Eastern Anatolian Kurdish tribal çuval. Circa 1880

-

Newspaper carpet, Aksehir 20th century

-

Small pattern Holbein carpet, Anatolia 16th century

-

An antique Uşak carpet

-

Antique Eastern Anatolian nomadic tribal rug. Circa 1880

-

Silk on silk Turkish carpet; Hadosan, Urgüp

-

Ancient Kirşehir prayer rug in the Tilavet room; Mevlâna Mausoleum, Konya

-

Vintage Turkish Kilim geometric patterned rug

-

Pile rug, circa 1875; Southwestern Anatolia

-

Silk Hereke Rug. Over 1200 knots per square inch

-

Central Anatolian lambs wool Yatak

-

Vintage Central Anatolian Yahyali tribal rug

-

Antique Gaziantep double prayer rug

-

Turkish çuval

-

Turkish tribal kelim

-

Vintage Uşak

-

.jpg)

Taspinar rug

-

Vintage Konya prayer seccade

-

Central Anatolian tribal weave rug. Early-mid 20th century

-

Anatolian nomadic Cicim; floor loom made.

-

Anatolian Yoruk tribal rug

-

Ottoman Era Kayseri silk prayer rug. Circa 1880's

-

Anatolian Ortakoy Region rug

-

Urgup rug featuring Kufic inner border

See also

- Bergama carpet

- Hereke carpet

- Islamic Art

- Konya Carpets and Rugs

- Kurdish rugs

- Milas carpet

- Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting

- Turkman rug

- Ushak carpet

- Persian rug

- Armenian carpet

References

- ↑ The Brukenthal Museum: The extraordinary value of the Anatolian Carpet. Brukenthalmuseum.ro. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ The historical importance of rug and carpet weaving in Anatolia. Turkishculture.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ Çatalhöyük.com: Ancient Civilization and Excavation. Catalhoyuk.com. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ Ancient Kilim Evidence Findings in Çatalhöyük. Turkishculture.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ The State Hermitage Museum: The Pazyryk Carpet. Hermitagemuseum.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ The Pazyryk Carpet, New Insights. W-ch-klose.de. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire By Pierre Briant: The Pazyryk Carpet Debate. Books.google.com. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ Joseph McMullan on the Pazaryk Carpet. Persiancarpetguide.com. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art: The debate on the origin of rugs and carpets. Books.google.com. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ Konya Carpet Findings. Turkishculture.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ King and Sylvester, p. 57

- ↑ Marco Polo in Konya. Art Fact.com. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ Memling Guls. Rjohnhowe.wordpress.com (2010-10-14). Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ Carpets of the Ottoman Period. Oldturkishcarpets.com (2012-01-20). Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ The Turkotek Salon: Anatolian Rugs, Tribal Distinctions. Turkotek.com. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ The Dominant role of Turkish Women and Girls in Turkish carpet weaving. Turkishculture.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ CA Geissler, TA Brun, I Mirbagheri, A Soheli, A Naghibi and H Hedayat (1981). "The Role of Women and Girls in traditional rug and carpet weaving". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 34 (12): 2776–2783. PMID 7315779.

- ↑ Selçuk Carpets. Old Turkish Carpets (2012-01-20). Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ Kurt Erdmann (1970). Seven hundred years of Oriental carpets. University of California Press. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-0-520-01816-7. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ Hereke Silk Carpet.com. Hereke Silk Carpet.com. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ Reference: Yetkin, Serare. Historical Turkish Carpets. Istanbul: Turkiye Is Bankasi, 1981. Turkish Culture.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ Construction Methods and Tools. Goldenyarncarpet.com. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ The Turkish Cultural Foundation: Construction Methods of Seljuk and Ottoman Court Era Rugs. Turkishculture.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ The Turkish Cultural Foundation: Our Traditional Cultural Heritage: Anatolian Turkish Hand-Woven Carpets And Kilims. Turkishculture.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carpets of Turkey. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||