Turin–Lyon high-speed railway

The Turin–Lyon high-speed railway is a planned 220 km/h railway line[1] that will connect the two cities and link the Italian and French high-speed rail networks. Work as up to now been limited to geological reconnaissance tunneling,[2] with actual construction the line planned to start in 2014–2015[3]

The line was part of "Corridor 6" – now modified and renamed as "mediterranean" – of the TEN-T Trans-European conventional rail network, which is not classed as a high-speed railway by the European Commission.[4] The new line will significantly shorten journey times and its reduced gradients compared to the existing line will allow heavier freight trains to travel between the two countries.

The core of the project is a 57 km base tunnel crossing the Alps between Susa valley in Italy and Maurienne in France.[5] The tunnel will be one of the longest rail tunnels in the world.

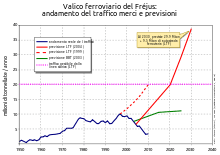

The project has been the subject of much criticism because of its cost, the currently decreasing traffic (both by motorway and rail),[6] the environmental risks involved in the construction of the tunnel and the supposed worthlessness of the new line (airplanes would still, after including time to and from the airport and through security, be somewhat faster over Milan-Paris[7]).

Problems about costs and the realism of traffic forecasts are also supported by a report by French Court of Audit, with some documents published in 2012.[8]

Preliminary studies

The worthiness of the new line has been the subject of much debate, before in Italy and recently also in France. An Italian governmental commission has been studying all the issues since 2006, after attempting impose the start of works in 2005 near Susa (Italy), resulted in strong confrontation between population and police.[9] Works of the commission between 2007 and 2009 have been collected in 7 papers (Quaderni) summarizing the results. An 8° paper focused on cost–benefit analysis was unveiled in June 2012 but criticized by some experts for contents and for publication timing.[citation needed]

The conventional line

A conventional double track railway connecting Turin with Lyon has been in operation since 1872 and is now electrified, with renovations (Italian side) between 1962 and 1984 and between 2001 and 2010.[10] The line connects Italy and France via the double track, 13.7 km long Fréjus Rail Tunnel,[11] opened in 1871 and renovated between 2001 and 2011.

The characteristics of the line vary widely along its length. The Osservatorio (see References) divides the Italian part into four sections:

- Modane - Bussoleno (Frejus tunnel and high valley section)

- Bussoleno - Avigliana (low valley section)

- Avigliana - Turin (metropolitan section)

- Turin node (urban section)

The maximum capacity of the first section (with the highest elevation and steepest gradients, and comprising the Fréjus tunnel) has been calculated as 226 trains/day, 350 days/year,[12] using the CAPRES model.[13] The study foresees a traffic of 180 freight trains per day. However, this value has to be lowered to about 150 freight trains per day due to logistical inefficiency, namely the asymmetric traffic levels between the two countries. A similar analysis for the whole year leads to a total of about 260 peak days per year.[14] These conditions define a maximum transport capacity per year of about 20 million tonnes taking into consideration inefficiencies, and a limit of about 32 million in "perfect" conditions.[15]

Other limitations are due to the impact of excessive train transits on the population living near the line. About 60,000 people live within 250 m of the line.[16]

The old conventional line is currently used for only 1/3 of its total capacity.[17] This is in part because its use is discouraged by important limitations such as a low limit on the maximum train height and the high gradient (26-30‰) of some sections of the track..

Traffic predictions

Future traffic from analysis of current data and macroeconomic predictions are summarized in the following table:[18]

| Without the new line | 2004 | 2025 | 2030 | Annual growth 2004-2030 |

| Alps – Total | 144,0 | 264,5 | 293,4 | 2,8% |

| Alps – Rail | 48,0 | 97,7 | 112,5 | 3,3% |

| Modane corridor – Total | 28,5 | 58,1 | 63,8 | 3,1% |

| Modane corridor – Rail | 6,5 | 15,8 | 16,4 | 3,6% |

| With the new line | 2004 | 2025 | 2030 | Annual growth 2004-2030 |

| Alps – Total | 144,0 | 264,5 | 293,4 | 2,8% |

| Alps – Rail | 48,0 | 111,4 | 130,7 | 3,9% |

| Modane corridor – Total | 28,5 | 63,5 | 76,5 | 3,9% |

| Modane corridor – Rail | 6,5 | 29,5 | 39,4 | 7,2% |

| Heavy vehicles (thousand per year) | 2004 | 2025 | 2030 | Annual growth 2004-2030 |

| Without the new line | 1.485 | 2.791 | 3.121 | 2,9% |

| With the new line | 1.485 | 2.244 | 2.447 | 1,9% |

Predictions by promoters of the new line show rail traffic on the Modane corridor about doubling compared to the reference scenario (without the construction of the new line). Anyway, not all the experts agree on the necessity for a new line connecting France and Italy on the Modane corridor, since the old line has wide margins for increase in traffic. This result could be reached with some renovation of the rail infrastructure by incentives on rail transport, rather than as a consequence of faster transit times and a lower price for freight shipping (due to less energy use, but without taking in account the cost of construction of the new line). However, the construction of a brand-new line would make the old infrastructure fully available for regional and suburban services, especially near the Turin node, and allow higher safety standards.[19]

The new line

The new railway will have a maximum gradient of 12.5‰, compared to 26% over a significant fraction of the old line and a maximum 30‰ over 1 km. This would allow heavier freight trains to transit at 100 km/h (62 mph), as well as a 220 km/h (140 mph) top speed for passenger trains.[20] The construction of the high-speed line will cut travel time from Milan to Paris from 7 hours to 4,[7] though these numbers are also contested[citation needed]).

No TAV movement

No TAV is an Italian movement against the construction of the line. The name comes from the Italian acronym for Treno Alta Velocità, high speed train. The movement's first demonstrations date back to 1995, but it became widely recognized during protests in 2005 and in the following years. Some No TAV protests have included clashes with police and disruption of highway traffic.[21]

The movement generally questions the worthiness, cost, and safety of the project, with support from studies, experts, and governmental documents from Italy, France, and Switzerland. The new line is deemed useless and too expensive, and its realization is believed to be driven by construction lobbies. The main objections are:

- Low level of saturation on the Frejus rail tunnel and stable or decreasing traffic also on Frejus road tunnel

- Economical feasibility in doubt due to high costs

- Danger of environmental disasters

- Concerns about health, due to the documented presence of Uranium and Asbestos in the mountains where the tunnel is supposed to be bored

Ideas against the construction of the new line have been summarized by members of the movement in a document containing 150 reasons against it[22] and in a wide number of specific documents and meetings.[23]

Critics of the No TAV movement, by contrast, characterize it as a typical NIMBY movement.

See also

- Mont d'Ambin base tunnel

- Lyon Turin Ferroviaire

- High-speed rail in Europe

- List of tunnels by length

- List of tunnels by location

- Treno Alta Velocità

- Rete Ferroviaria Italiana

- Réseau Ferré de France

Notes

- ↑ (Italian) Nuova linea Torino-Lione parte comune tratta italiana - Progetto in variante - Studio d'impatto ambientale - sintesi non tecnica 9-7-2010 (document PP2 C3C TS3 0105A AP NOT)

- ↑ "Close-up on works". LTF. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ http://www.ltf-sas.com/pages/articles.php?art_id=79%7CCalendario

- ↑ Decision No 661/2010/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 July 2010 on Union guidelines for the development of the trans-European transport network

- ↑ "The Alpine tunnels". LTF. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ http://www.bav.admin.ch/verlagerung/01529/index.html?lang=fr

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Dichiarazioni alla stampa del Presidente Monti al termine della riunione sui lavori di realizzazione della Tav tratto Torino-Lione." [Press conference by president Mario Monti]. Italian Government. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ ,

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 4

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 16

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 17

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 30

- ↑ CAPacité des RESéaux ferroviaires, Rivier, École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 31

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 32

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - pp. 33-34

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 35. Data are from 2007, when capacity was also reduced until 2007-2010 due to modernization works in progress.

- ↑ Quaderno 2 - p. 18

- ↑ Quaderno 2 - pp. 36-39

- ↑ "The base tunnel". LTF. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ↑ Tim Phillips, "Six Members of the No-TAV Movement Sentenced for Crimes During Protests, but Two Acquitted", Activist Defense, June 5, 2013.

- ↑ from Pro Natura Torino.

- ↑ For specific documentation in English see http://www.notavtorino.org/documenti/inglese/indice.htm

References

- Quaderno 1: Linea storica - Tratta di valico [Book 1: Old line - upper section]. Osservatorio Ministeriale per il collegamento ferroviario Torino-Lione, Rome, May 2007

- Quaderno 2: Scenari di traffico - Arco Alpino [Book 2: Traffic scenarios - Alps passes]. Osservatorio Ministeriale per il collegamento ferroviario Torino-Lione, Rome, June 2007

- Quaderno 3: Linea storica - Tratta di valle [Book 3: Old line - lower section]. Osservatorio Ministeriale per il collegamento ferroviario Torino-Lione, Rome, December 2007

External links

- RFI - Rete Ferroviaria Italiana - owner of the Italian rail infrastructure

- RFF - Réseau Ferré de France - owner of the French rail infrastructure

- LTF - Lyon Turin Ferroviaire - The company responsible for the Turin-Lyon line, owned 50% by RFI and 50% by RFF.

- http://www.notavtorino.org/documenti/inglese/indice.htm - Some documents against new railway in English

- (Italian) TAV Turin-Lyon planned line in Google Earth/Maps