Tupolev Tu-160

The Tupolev Tu-160 (Russian: Туполев Ту-160, NATO reporting name: Blackjack) is a supersonic, variable-sweep wing heavy strategic bomber designed by the Tupolev Design Bureau in the Soviet Union. Although several civil and military transport aircraft are larger in overall dimensions, the Tu-160 is currently the world's largest combat aircraft, largest supersonic aircraft, and largest variable-sweep aircraft built. Only the North American XB-70 Valkyrie had higher empty weight and maximum speed. In addition, the Tu-160 has the heaviest takeoff weight of any military aircraft besides transports.

Entering service in 1987, the Tu-160 was the last strategic bomber designed for the Soviet Union. 16 aircraft are in use with the Russian Air Force . A planned modernisation of 10 aircraft to Tu-160M standard has been announced.

Development

The first competition for a supersonic strategic heavy bomber was launched in the Soviet Union in 1967. In 1972, the Soviet Union launched a new multi-mission bomber competition to create a new supersonic, variable-geometry ("swing-wing") heavy bomber with a maximum speed of Mach 2.3, in direct response to the US Air Force B-1 bomber project. The Tupolev design, dubbed Aircraft 160M, with a lengthened flying wing layout and incorporating some elements of the Tu-144, competed against the Myasishchev M-18 and the Sukhoi T-4 designs.[1]

Work on the new Soviet bomber continued despite an end to the B-1A, and in the same year, the design was accepted by the government committee. The prototype was photographed by an airline passenger at a Zhukovsky Airfield in November 1981, about a month before the aircraft's first flight on 18 December 1981. Production was authorized in 1984, beginning at Kazan Aircraft Production Association.[citation needed]

Modernization

Like many Soviet weapon systems, the Tu-160 has struggled to overcome unreliable components and a lack of maintenance during the 1990s. The original systems were faulty and required a complete rework using modern microchips and computer boards,[2] such that the aircraft was not formally accepted into Russian service until the new avionics had been tested in late 2005.[3] The upgrade also integrated a new long-range cruise missile. Although the Russians have talked up the progress of the modernisation project, it seems to have been restricted by limitations of the industrial base and the more pressing need to keep aircraft flying. It was due to start after the delivery of a new-build aircraft in 2006[3] but the "first modernised Tu-160" delivered in July 2006[4] did not receive new avionics, although they were planned for the new airframe.[5] The modernisation now appears to have been split into two phases, concentrating on life extension with some communication/navigation updates to start with, followed by 10 aircraft receiving new engines and capability upgrades after 2016.[2] The first refitted aircraft was delivered to the VVS in May 2008;[6] a contract to overhaul three aircraft in 2013 cost RUR3.4 billion (US$103m).[6]

Although the phase I update was due to be completed by 2016, industrial limitations may delay it to 2019 or beyond.[7] There is a particular problem with the engines; although Kuznetsov designed an NK-32M engine that improved the reliability of the troublesome NK-32 engines, its successor company has struggled to deliver working units. Metallist-Samara JSC has not produced new engines for a decade and when it was given a contract in 2011 to overhaul 26 of the existing engines, it managed just four in two years.[7] There are problems with the ownership of the company and it lacks finance to build a new production line;[7] it insists it needs an order of 20 engines per year but the government is only prepared to pay for 4-6 engines per year.[8] A much-improved gas generator has been benchtested, but may not enter production until 2016.[2] Russia has consistently talked of building new Tu-160 airframes but the only new-builds since the early 1990s have come from half-built aircraft of the original production run and new production seems unlikely until the industrial issues are resolved.

Design

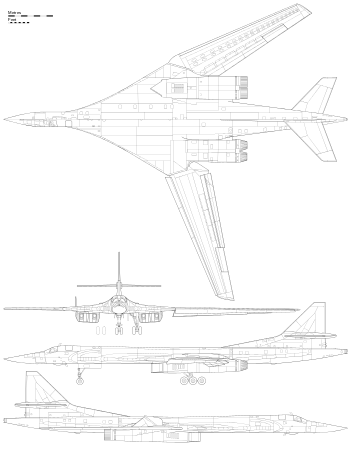

The Tu-160 is a variable-geometry wing aircraft. The aircraft employs a fly-by-wire control system with a blended wing profile, and full-span slats are used on the leading edges, with double-slotted flaps on the trailing edges.[citation needed]

The Tu-160 is powered by four Kuznetsov NK-321 afterburning turbofan engines, the most powerful ever fitted to a combat aircraft. Unlike the American B-1B Lancer, which reduced the original Mach 2+ requirement for the B-1A to achieve a smaller radar profile, the Tu-160 retains variable intakes, and is capable of reaching Mach 2.05 speed at altitude.[9]

The Tu-160 is equipped with a probe-and-drogue in-flight refueling system for extended-range missions, although it is rarely used. The Tu-160's internal fuel capacity of 130 tons gives the aircraft a roughly 15-hour flight endurance at a cruise speed of around 850 km/h (Mach 0.77, 530 mph) at 9,145 m (30,003 ft).[10] In February 2008, Tu-160 bombers and Il-78 refueling tankers practiced air refueling during air combat exercise, as well as MiG-31, A-50 and other Russian combat aircraft.[11]

Although the Tu-160 was designed for reduced detectability to both radar and infrared, it is not a stealth aircraft. Nevertheless, Lt. Gen. Igor Khvorov claimed that Tu-160s managed to penetrate the US sector of the Arctic undetected on 25 April 2006, leading to a USAF investigation according to a Russian source.[12]

The Tu-160 has a crew of four (pilot, co-pilot, bombardier, and defensive systems operator) in K-36DM ejection seats.[citation needed]

Weapons are carried in two internal bays, each capable of holding 20,000 kg (44,400 lb) of free-fall weapons or a rotary launcher for nuclear missiles; additional missiles may also be carried externally. The aircraft's total weapons load capacity is 40,000 kg (88,185 lb).[13] However, no defensive weapons are provided; the Tu-160 is the first unarmed post-World War II Soviet bomber.

A demilitarized, commercial version of the Tu-160, named Tu-160SK, was displayed at Asian Aerospace in Singapore in 1994 with a model of a small space vehicle named Burlak[14] attached underneath the fuselage.

While similar in appearance to the American B-1 Lancer, the Tu-160 is a different class of combat aircraft, its primary role being a standoff missile platform (strategic missile carrier). The Tu-160 is also larger and faster than the B-1B and has a slightly greater combat range, though the B-1B has a larger combined payload.[15] Another significant difference is that the colour scheme on the B-1B Lancer is usually radar-absorbent black, the Tu-160 is painted with anti-flash white, giving it the nickname among Russian airmen "White Swan".[16]

Operational history

The Tu-160 began service in April 1987[citation needed] with the 184 Guards Bomber Regiment, based at Pryluky, Soviet Union.

Squadron deployments to Long Range Aviation began in April 1987 before the Tu-160 was first presented to the public in a parade in 1989. In 1989 and 1990 it set 44 world speed flight records in its weight class. Until 1991, 19 aircraft served in the 184th Guards Heavy Bomber Regiment (GvTBAP) in Pryluky in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, replacing Tu-16 and Tu-22M3 aircraft. In 1992, Russia unilaterally suspended its flights of strategic aviation in remote regions.

The Fall of the Soviet Union saw 19 aircraft stationed in the newly independent Ukraine. On 25 August 1991, the Ukrainian parliament decreed that the country would take control of all military units on its territory and a Defence Ministry was created the same day. By the mid-1990s, the Pryluky Regiment had lost its value as a combat unit. The 184th GvTBAP's 19 "Blackjacks" were effectively grounded because of a lack of technical support, spare parts and fuel. At this time, Ukraine considered the Tu-160s more of a bargaining chip in their economic negotiations with Russia. They were of very limited value to Ukraine from a military standpoint, but discussions with Russia concerning their return bogged down. The main bone of contention was the price. While Russian experts, who examined the aircraft at the Pryluky Air Base in 1993 and 1996, assessed their technical condition as good, the price of $3 billion demanded by Ukraine was unacceptable. The negotiations led to nowhere and in April 1998, Ukraine decided to commence scrapping the aircraft under the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Agreement. In November, the first Tu-160 was ostentatiously chopped up at Pryluky.[17]

In April 1999, immediately after NATO began its air attacks against Serbia, Russia resumed talks with Ukraine about the strategic bombers. This time they proposed buying back eight Tu-160s and three Tu-95MS models manufactured in 1991 (those in the best technical condition), as well as 575 Kh-55MS missiles. An agreement was finally reached and a contract valued at $285 million was signed. That figure was to be deducted from Ukraine's debt for natural gas. A group of Russian military experts went to Ukraine on 20 October 1999 to prepare the aircraft for the trip to Engels-2 air base. The first two (a Tu-160 and a Tu-95MS) departed Pryluky on 5 November. During the months that followed, the other seven "Blackjacks" were brought to Engels, with the last two arriving on 21 February 2001.[17]

Along with the re-purchase of the aircraft from Ukraine, Russia's Defence Ministry sought other ways of rebuilding the fleet at Engels. In June 1999, the Ministry placed a contract with the Kazan Aircraft Production Association for a delivery of a single, almost complete, bomber. The aircraft was the second aircraft in the eighth production batch and it arrived at Engels on 10 September. It was commissioned into service as "07" on 5 May 2000.[17]

The unit that was operating the fleet from Engels was 121st Guards Heavy Bomber Regiment. It formed up in the spring of 1992 and by 1994 it had received 6 aircraft. By the end of February 2001, the fleet stood at 15 with the addition of the eight aircraft from Ukraine and the new-build.[17] As of 2001, six additional Tu-160 have served as experimental aircraft at Zhukovski, four remaining airworthy.

The Air Force fleet was reduced to 14 by the crash of the Mikhail Gromov during flight trials of a replacement engine on 18 September 2003.[18] It would be brought up to 16 aircraft by the completion of a part-built aircraft in June 2006 and the delivery of the Vitaly Kopylov on 29 April 2008.[19] Following acceptance of the testing of the prototype of the long-awaited avionics upgrades the Tu-160 formally entered service with the Russian Air Force by a presidential decree of 30 December 2005.[20][3]

On 17 August 2007, Putin announced that Russia was resuming the strategic aviation flights stopped in 1991, sending its bomber aircraft on long-range patrols.[21] On 14 September 2007, British and Norwegian fighters intercepted two Tu-160s which breached NATO airspace near the UK and Finland.[22] On 25 December 2007, two Blackjacks came close to Danish airspace, and two Danish Air Force F-16 Fighting Falcons scrambled to intercept and identify them.[23]

According to Russian government sources, on 11 September 2007, a Tu-160 was used to drop the massive fuel-air explosive device, the Father of All Bombs, for its first field test.[24] However, some military analysts expressed skepticism that the weapon was actually delivered by a Blackjack.[25]

On 28 December 2007, the first flight of a new Tu-160 was reported to have taken place following completion of the aircraft at the Kazan Aviation Plant.[26] After flight testing, the bomber joined the Russian Air Force on 29 April 2008, bringing the total number of aircraft in service to 16. One new Tu-160 is expected to be built every one to two years until the active inventory reaches 30 or more aircraft by 2025–2030.[27][28]

On 10 September 2008, two Russian Tu-160 landed in Venezuela as part of military manoeuvres, announcing an unprecedented deployment to Russia's ally at a time of increasingly tense relations between Russia and the United States. The Russian Ministry of Defence said Vasily Senko and Aleksandr Molodchiy were on a training mission. It said in a statement carried by Russian news agencies, that the aircraft would conduct training flights over neutral waters before returning to Russia. Its spokesman added that the aircraft were escorted by NATO fighters as they flew across the Atlantic Ocean.[29]

On 12 October 2008, a number of Tu-160 bombers were involved in the largest Russian strategic bomber exercise since 1984. A total of 12 bombers including Tu-160 Blackjack and Tu-95 Bear conducted a series of launches of their cruise missiles. Some bombers launched a full complement of their missiles. It was the first time that a Tu-160 had ever fired a full complement of missiles.[30]

On 10 June 2010, two Tu-160 bombers carried out a record-breaking 23-hour patrol with a planned flight range of 18,000 km (9,700 nmi). The bombers flew along the Russian borders and over neutral waters in the Arctic and Pacific Oceans.[31]

Russian media reports in August 2011 claimed that only four of the VVS' sixteen Tu-160 were flightworthy.[7] By mid-2012 Flight reported eleven were combat-ready[2] and between 2011-13 eleven were photographed in flight.[32]

On November 1, 2013, Aleksandr Golovanov and Aleksandr Novikov went into Colombian airspace in two different occasions without receiving previous clearance from the Colombian Government. This sparked a note of protest on the first incursion and on the second one, Kfir jets stationed at Barranquilla were scrambled to intercept and escort the two Blackjacks out of Colombian airspace.[33][34]

Variants

- Tu-160: Production version.

- Tu-160S: designation used for serial Tu-160s when needed to separate them from all the pre-production and experimental aircraft.[35]

- Tu-160V: proposed liquid hydrogen fueled version (see also Tu-155).[35]

- Tu-160 NK-74: proposed upgraded (extended range) version with NK-74 engines.[35]

- Tu-160M: upgraded version that features new weaponry, improved electronics and avionics, which double its combat effectiveness.[36] Will carry the hypersonic Kh-90 (3M25 Meteorit-A) missiles.

- Tu-160P (Tu-161): proposed very long-range escort fighter/interceptor version.

- Tu-160PP: proposed electronic warfare version carrying stand-off jamming and ECM gear (Russian: ПП – постановщик помех).

- Tu-160R: proposed strategic reconnaissance version.

- Tu-160SK: proposed commercial version, designed to launch satellites within the "Burlak" (Russian: Бурлак, "hauler") system.[35]

Operators

- Russian Air Force - 16 were in service (12 combat and four in training) as of April 2008,[37] with the 121st Guards Heavy Bomber Regiment at Engels/Saratov.[38] As of 2013, 11 Tu-160s are combat-ready.[39]

Former

- Ukrainian Air Force inherited 19 Tu-160s from the former Soviet Union, but subsequently handed over eight Tu-160s to Russia as exchange for debt relief in 1999; the remainder have been withdrawn from service.

- 1 in museum of the strategic aviation in Poltava[40]

- Soviet Air Force (transferred to Russian and Ukrainian Air Forces in 1991)

- 184th Guards Heavy Bomber Regiment (TBAP), Pryluky, Ukrainian SSR

Specifications (Tu-160)

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2003–2004,[13]

General characteristics

- Crew: 4 (pilot, co-pilot, bombardier, defensive systems operator)

- Length: 54.10 m (177 ft 6 in)

- Wingspan:

- Spread (20° sweep): 55.70 m (189 ft 9 in)

- Swept (65° sweep): 35.60 m (116 ft 9¾ in)

- Height: 13.10 m (43 ft 0 in)

- Wing area:

- Spread: 400 m² (4,306 ft²)

- Swept: 360 m² (3,875 ft²)

- Empty weight: 110,000 kg (242,505 lb; operating empty weight)

- Loaded weight: 267,600 kg (589,950 lb)

- Max. takeoff weight: 275,000 kg (606,260 lb)

- Powerplant: 4 × Samara NK-321 turbofans

- Dry thrust: 137.3 kN (30,865 lbf) each

- Thrust with afterburner: 245 kN (55,115 lbf) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.05 (2,220 km/h, 1,200 knots, 1,380 mph) at 12,200 m (40,000 ft)

- Cruise speed: Mach 0.9 (960 km/h, 518 knots, 596 mph)

- Range: 12,300 km (7,643 mi)practical range without in-flight refuelling, Mach 0.77 and carrying 6 × Kh-55SM dropped at mid range and 5% fuel reserves[41]

- Combat radius: 7,300 km[42] (3,994 nmi, 4,536 mi,)2,000 km (1,080 nmi, 1,240 mi) at Mach 1.5[13]

- Service ceiling: 15,006 m (49,235 ft)

- Rate of climb: 70 m/s (13,860 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 742 kg/m² with wings fully swept (152 lb/ft²)

- lift-to-drag: 18.5–19, while supersonic it is above 6.[43]

- Thrust/weight: 0.37

- Two internal bays for 40,000 kg (88,185 lb) of ordnance including

- Two internal rotary launchers each holding 6× Raduga Kh-55SM/101/102 cruise missiles (primary armament) or 12× Raduga Kh-15 short-range nuclear missiles.

See also

- PAK DA

- Tupolev Tu-134UBL, used for Tu-160 pilot training

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ Sergeyev, Pavel. "Белый лебедь" (Russian). Lenta.ru, 30 April 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Karnozov, Vladimir (15 Oct 2012). "IN FOCUS: Russian's next-generation bomber takes shape". Flight International. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Fomin, Andrey. "Ту-160 принят на вооружение". Take-Off (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2008-03-15.

- ↑ "Russia can hope for new Blackjack bomber in 2006 – Ivanov." rian.ru, Russian News and Information Agency, 5 July 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "Tu-160 returns from overhaul". Russian strategic nuclear forces. 5 July 2006.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Jennings, Gareth (28 July 2013). "Russia continues Tu-160 'Blackjack' bomber modernisation work". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Retrieved 2013-11-21.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Johnson, Reuben F (11 November 2013). "Further delays for modernisation of Russian Air Force Tu-160 bombers". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Retrieved 2013-11-21.

- ↑ Kramnik, Ilya (16 September 2011). Izvestia (in Russian) http://izvestia.ru/news/500938

|url=missing title (help). - ↑ "Russian Tu-160 Blackjack strategic bomber". RIA Novosti. 2013.

- ↑ "Aircraft Museum – Tu-160 'Blackjack'." Aerospaceweb.org, 16 August 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ "Tu-160 bombers practice air refueling in Feb 2008 exercises" AirForceWorld.com. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ↑ "Russian bombers flew undetected across Arctic – AF commander." RIA Novosti, 22 April 2006. Retrieved 22 April 2008

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Jackson 2003, pp. 425–426.

- ↑ Burlak

- ↑ The Directory of the World's Weapons 1996, p. 140.

- ↑ “'White swan’ – Russian supersonic aircraft." Moscow Top News, 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Butowski, Piotr. "Russia's Strategic Bomber Force". Combat Aircraft 4 (6): 552–565.

- ↑ Associated Press (18 September 2003). "Russian supersonic bomber crashes". Ananova. Archived from the original on 2003-09-20.

- ↑ Jane's All the World's Aircraft. McGraw-Hill. 2009. p. 42.

- ↑ Jane's All the World's Aircraft. McGraw-Hill. 2009. p. 522.

- ↑ "Russia orders long-range bomber patrols." USA Today, 17 August 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ Satter, Raphael G. "NATO jets intercept Russian warplanes." USA Today, 14 September 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ "Danish fighter jets v. Russian bombers: 18-minute chase." russiatoday.ru, 26 December 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ "Russia tests giant fuel-air bomb." BBC News, 12 September 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ Axe, David and Daria Solovieva. "Did Russia Stage the Father of All Bombs Hoax?" Wired, 4 October 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "New serial Tu-160 Blackjack bomber undergoes flight test." rian.ru, Russian News and Information Agency, 12 December 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "Russian Air Force receives new Tu-160 strategic bomber'" RIA Novosti, 10 January 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "На КАПО им.Горбунова испытали новый серийный Ту-160" (Russian). Tatar-Inform Information Agency, Kazan, 6 January 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2009

- ↑ "Russian bombers land in Venezuela." BBC News, 11 September 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "Russia plans biggest missile test for 24 years." The Daily Telegraph, 7 October 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "Russian strategic bombers complete record duration flight." The Moscow News via mn.ru, 10 June 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ↑ Axe, David (13 November 2013). "We Just Hunted Down All of Russia’s Long-Range Bombers". War is Boring. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ http://www.elespectador.com/noticias/politica/colombia-enviara-nota-de-protesta-rusia-violacion-del-e-articulo-456719

- ↑ http://www.eltiempo.com/politica/aviones-rusos-violaron-espacio-aereo-de-colombia_13161644-4

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Aviation and Cosmonautics magazine, 5.2006, pp. 10–11. ISSN 168-7759.

- ↑ http://en.rian.ru/military_news/20120207/171200584.html

- ↑ "Ъ-Власть – Куда летит российская авиация" (in Russian). kommersant.ru. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ↑ "Russian Air Force receives new Tu-160 strategic bomber." RIA Novosti. 29 April 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ Karnozov, Vladimir. "In focus: Russian's next-generation bomber takes shape." Flight International, 15 October 2012.

- ↑ "Музей дальней авиации, Полтава" (in Russian).. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ↑ Taylor 1996, p. 103.

- ↑ "Tu-160 Blackjack (Tupolev)." globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ БОМБАРДИРОВЩИКА Ту-160." ('Tu-160 bomber specifications') airforce.ru. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

Bibliography

- The Directory of the World's Weapons. Leicester, UK: Blitz Editions, 1996. ISBN 978-1-85605-348-8.

- Eden, Paul (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- Jackson, Paul. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2003–2004. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group, 2003. ISBN 0-7106-2537-5.

- Taylor, Michael J. H. Brassey's World Aircraft & Systems Directory. London: Brassey's, 1996. ISBN 1-85753-198-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tupolev Tu-160. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||