Trinity Church (Manhattan)

|

Trinity Church and Graveyard | |

| |

|

Trinity Church from Wall Street | |

| Location |

79 Broadway Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°42′29″N 74°0′44″W / 40.70806°N 74.01222°WCoordinates: 40°42′29″N 74°0′44″W / 40.70806°N 74.01222°W |

| Built | 1846 |

| Architect | Richard Upjohn |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | 76001252 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 8, 1976[1] |

| Designated NHL | December 8, 1976,[2] |

| Designated NYCL | August 16, 1966 |

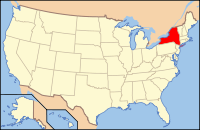

Trinity Church, at 79 Broadway in lower Manhattan, is a historic, active, well-endowed[3] parish church in the Episcopal Diocese of New York. Trinity Church is near the intersection of Wall Street and Broadway, in New York City, New York.

History and architecture

In 1696, Governor Benjamin Fletcher approved the purchase of land in Lower Manhattan by the Church of England community for construction of a new church. The parish received its charter from King William III on May 6, 1697. Its land grant specified an annual rent of sixty bushels of wheat.[4] The first rector was William Vesey (for whom nearby Vesey Street is named), a protege of Increase Mather, who served for 49 years until his death in 1746.

First Trinity Church

The first Trinity Church building, a modest rectangular structure with a gambrel roof and small porch, was constructed in 1698. According to historical records, Captain William Kidd lent the runner and tackle from his ship for hoisting the stones.[5][6]

Anne, Queen of Great Britain, increased the parish's land holdings to 215 acres (870,000 m2) in 1705. Later, in 1709, William Huddleston founded Trinity School as the Charity School of the church, and classes were originally held in the steeple of the church. In 1754, King's College (now Columbia University) was chartered by King George II of Great Britain and instruction began with eight students in a school building near the church.

During the American Revolutionary War the city became the British military and political base of operations in North America, following the departure of General George Washington and the Continental Army shortly after Battle of Long Island and subsequent local defeats. Under British occupation clergy were required to be Loyalists, while the parishioners included some members of the revolutionary New York Provincial Congress, as well as the First and Second Continental Congresses.

The church was destroyed in the Great New York City Fire of 1776, which started in the Fighting Cocks Tavern, destroying nearly 500 buildings and houses and leaving thousands of New Yorkers homeless. Six days later, most of the city's volunteer firemen followed General Washington north.

The Rev. Samuel Provoost, was appointed Rector of Trinity (1784-1800) in 1784 and the New York State Legislature ratified the charter of Trinity Church, deleting the provision that asserted its loyalty to the King of England. Whig patriots were appointed as vestrymen. In 1787, Provoost was consecrated as the first Bishop of the newly formed Diocese of New York. Following his 1789 inauguration at Federal Hall, George Washington attended Thanksgiving service, presided over by Bishop Provoost, at St. Paul's Chapel, a chapel of the Parish of Trinity Church. He continued to attend services there until the second Trinity Church was finished in 1790. St. Paul's Chapel is currently part of the Parish of Trinity Church and is the oldest public building in continuous use in New York City.

Second Trinity Church

Construction on the second Trinity Church building began in 1788; it was consecrated in 1790. The structure was torn down after being weakened by severe snows during the winter of 1838–39.

Third Trinity Church

The third and current Trinity Church was finished in 1846 and at the time of its completion its 281-foot (86 m) spire and cross was the highest point in New York until being surpassed in 1890 by the New York World Building.

In 1843, Trinity Church's expanding parish was divided due to the burgeoning cityscape and to better serve the needs of its parishioners. The newly formed parish would build Grace Church, to the north on Broadway at 10th street, while the original parish would re-build Trinity Church, the structure that stands today. Both Grace and Trinity Churches were completed and consecrated in 1846.

In 1876-1877 a reredos and altar was erected in memory of William Backhouse Astor, Sr., to the designs of architect Frederick Clarke Withers.

Architectural historians consider the present, 1846 Trinity Church building, designed by architect Richard Upjohn, a classic example of Gothic Revival architecture. In 1976 the United States Department of the Interior designated Trinity Church a National Historic Landmark because of its architectural significance and its place within the history of New York City.[2][7][8]

When the Episcopal Bishop of New York consecrated Trinity Church on Ascension Day May 1, 1846, its soaring Neo-Gothic spire, surmounted by a gilded cross, dominated the skyline of lower Manhattan. Trinity was a welcoming beacon for ships sailing into New York Harbor.

On July 9, 1976 Queen Elizabeth II visited Trinity Church. Vestrymen presented her with a symbolic "back rent" of 279 peppercorns. King William III, in 1697, gave Trinity Church a charter that called for the parish to pay an annual rent of one peppercorn to the crown. Since 1993, Trinity Church has hosted the graduation ceremonies of the High School of Economics and Finance. The school is located on Trinity Place, a few blocks away from the church.

During the September 11, 2001 attacks, as the 1st Tower collapsed, people took refuge from the massive debris cloud inside the church. Falling wreckage from the collapsing tower knocked over a giant sycamore tree that had stood for nearly a century in the churchyard of St. Paul's Chapel, which is part of Trinity Church's parish and is located several blocks north of Trinity Church. Sculptor Steve Tobin used its roots as the base for a bronze sculpture that stands next to the church today.

Burial grounds

There are three burial grounds closely associated with Trinity Church. The first is Trinity Churchyard, at Wall Street and Broadway, in which Alexander Hamilton, William Bradford, Franklin Wharton, Robert Fulton, Captain James Lawrence and Albert Gallatin are buried. The second is Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum on Riverside Drive at 155th Street, formerly the location of John James Audubon's estate, in which are interred John James Audubon, Alfred Tennyson Dickens, John Jacob Astor, and Clement Clarke Moore. It is the only active cemetery remaining in the borough of Manhattan. The third is the Churchyard of St. Paul's Chapel, where memorials to the United Irishmen Addis Emmet and Dr. William MacNeven are located.

Bells

The tower of Trinity Church currently contains 23 bells the heaviest of which weighs 27 cwt.

Eight of these bells were cast for the tower of the second church building and were hung for ringing in the English change ringing style. Three more bells were added later. In 1946 these bells were adapted for swing chiming and sounded by electric motors.

A project to install a new ring of 12 additional change ringing bells was initially proposed in 2001 but put on hold in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, which took place three blocks north of the church. This project came to fruition in 2006, thanks to funding from the Dill Faulkes Educational Trust. These new bells form the first ring of 12 change-ringing bells ever installed in a church in the United States. The installation work was carried out by Taylors, Eayre and Smith of Loughborough, England, in September 2006.

In late 2006, the ringing of the bells for bell practice and tuning caused much concern to local residents, some of whose windows and residences are less than 100 feet at eye level from the bell tower. The church then built a plywood deck right over the bells and placed shutters on the inside of the bell chamber's lancet windows. With the shutters and the plywood deck closed, the sound of the bells outside the tower is minimal. The shutters, and hatches in the plywood deck, are opened for public ringing.

Public ringing takes place before and after 11:15 a.m. Sunday service and on special occasions, such as 9/11 commemorations, weddings, and ticker-tape parades. Details of the individual bells can be found at: Dove's Guide for Church Bellringers.

Doors

Trinity Church has three sets of impressive bronze doors conceived by Richard Morris Hunt. These date from 1893 and were produced by Karl Bitter (east door), J. Massey Rhind (south door) and Charles Henry Niehaus (north door). The doors were a gift from William Waldorf Astor, 1st Viscount Astor in memory of John Jacob Astor III. The north and east door each consist of six panels from Church history or the Bible and the south door depicts the history of New York in its six panels.

Services

Trinity Church offers a full schedule of prayer and Eucharist services throughout the week and is also available for special occasions such as weddings and baptisms. In addition to its historical daily worship, Trinity Church provides Christian fellowship and outreach to the community, the city, the nation and the world.

Trinity Church has a very rich music program with an annual budget of $2.5 million as of 2011.[3] Concerts at One has been providing live professional classical and contemporary music for the Wall Street community since 1969, and the church has several organized choirs including the Trinity Choir, featured Sunday mornings on WQXR 105.9 FM in New York City.

The church also houses a museum with exhibits about the history of the church, as well as changing art, religious and cultural exhibits. Guided tours of the church are offered daily at 2 PM.

Property holdings

Beginning in the 1780s, the church's claim on 62 acres of Queen Anne's 1705 grant was contested in the courts by descendants of a 17th-century Dutchwoman, Anneke Jans Bogardus, who, it was claimed, held original title to that property. The basis of the lawsuits was that only five of Bogardus' six heirs had conveyed the land to the English crown in 1671.[9][10] Numerous times over the course of six decades, the claimants asserted themselves in court, losing each time. The attempt was even revived in the 20th century.

Disclosure resulting from a lawsuit filed by a parishioner revealed total assets of about $2 billion as of 2011.[3] Although Trinity Church has sold off much of the land that was part of the royal grant from Queen Anne,[9] it is still one of the largest landowners in New York City with 14 acres of Manhattan real estate including 5.5 million square feet of commercial space in Hudson Square.[3][11] The parish's annual revenue from its real estate holdings was $158 million in 2011 with net income of $38 million,[3] making it perhaps one of the richest individual parishes in the world.[9]

Staff

- The Rev. Dr. James Herbert Cooper (the Rector)

- Annual salary in 2011: $475,000, with pension and rectory included, $1.3 million[3]

- The Rev. Canon Anne Mallonee (the Vicar)

- The Rev. Matthew Heyd (Director, Faith in Action)

- The Rev. Mark Francisco Bozzuti-Jones (Priest for Pastoral Care and Nurture)

- The Rev. Daniel Simons (Priest for Liturgy, Hospitality & Pilgrimage)

- Bob Scott (Director, Faith Formation)

- Julian Wachner (Director, Music and the Arts)

Relationship with Occupy Wall Street

Trinity is located near Zuccotti Park, the location of the Occupy Wall Street protest. It has offered both moral and practical support to the demonstrators but balked when church-owned land adjoining Juan Pablo Duarte Square was demanded for an encampment. While the church hierarchy supports their position they have been criticized by others within the Anglican movement, most notably, Archbishop Desmond Tutu.[12] On Saturday, December 17, occupiers, accompanied by a few clergy, attempted to occupy the land (known as LentSpace), which is surrounded by a chain-link fence. After demonstrating in Duarte Park and marching on the streets surrounding the park, occupiers climbed over[13] and under the fence. Police responded by arresting about 50 demonstrators, including at least three Episcopal clergymen and a Roman Catholic nun.[14]

References

Notes

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Trinity Church and Graveyard". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-11.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Sharon Otterman (April 24, 2013). "Trinity Church Split on How to Manage $2 Billion Legacy of a Queen". The New York Times. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ↑ "TRINITY CHURCH PROPERTY.; Outline of the Legal History of the Trinity "Church Farm."". The New York Times. November 18, 1859.

- ↑ Trinity Church - Historical Timeline

- ↑ "Question of the Day: Trinity's Very Own Pirate?". The Archivist's Mailbag. Trinity Church. November 19, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination". National Park Service. August 1976.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination (photos)". National Park Service. August 1976.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Nevius, Michelle and Nevius, James. Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City. New York: Free Press, 2009. ISBN 141658997X, pp.22-23

- ↑ "A Dutchwoman's Farm.; The Hon. James W. Gerard On The Anneke Jans Bogardus Claims". The New York Times. May 7, 1879.

- ↑ Trinity Real Estate

- ↑ Matt Flegenheimer (December 16, 2011). "Occupy Group Faults Church, a Onetime Ally". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ↑ Nathan Schneider (December 19, 2011). "Re-Occupy: A Movement Seeks a Sanctuary: On occupying Trinity Church—and the Occupy movement's relationship with established institutions.". Yes!. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ↑ Al Baker; Colin Moynihan (December 17, 2011). "Arrests as Occupy Protest Turns to Church". The New York Times. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trinity Church (New York City). |

- Trinity Church – Official website for Trinity Church

- Trinity Television and New Media – Trinity Videos and Resources

- Trinity History – Trinity Historical and Archival Resources

- Trinity Real Estate – Official website for Trinity Church's real estate holdings

- The Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine – Mother Church of the Episcopal Diocese of New York

- National Historic Register Number: 76001252

- Trinity Tombstone & Churchyard Gallery

- Search Churchyard burials and registers of official acts

| |||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||