Trigeminal neuralgia

| Trigeminal neuralgia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

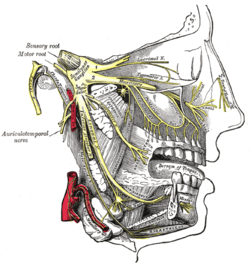

Detailed view of the trigeminal nerve and its three major divisions (shown in yellow): the ophthalmic nerve (V1), the maxillary nerve (V2), and the mandibular nerve (V3) | |

| ICD-10 | G50.0, G44.847 |

| ICD-9 | 350.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 13363 |

| MedlinePlus | 000742 |

| eMedicine | emerg/617 |

| MeSH | D014277 |

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN, or TGN), also known as prosopalgia,[3] or Fothergill's disease[4] is a neuropathic disorder characterized by episodes of intense pain in the face, originating from the trigeminal nerve. The clinical association between TN and hemifacial spasm is the so-called tic douloureux.[5] It has been described as among the most painful conditions known to humankind.[6] It is estimated that 1 in 15,000 or 20,000 people suffer from TN, although the actual figure may be significantly higher due to frequent misdiagnosis. In a majority of cases, TN symptoms begin appearing more frequently over the age of 50, although there have been cases with patients being as young as three years of age. It is more common in females than males.[7]

The trigeminal nerve is a paired cranial nerve that has three major branches: the ophthalmic nerve (V1), the maxillary nerve (V2), and the mandibular nerve (V3). One, two, or all three branches of the nerve may be affected. 10-12% of cases are bilateral (occurring on both the left and right sides of the face). Trigeminal neuralgia most commonly involves the middle branch (the maxillary nerve or V2) and lower branch (mandibular nerve or V3) of the trigeminal nerve,[8] but the pain may be felt in the ear, eye, lips, nose, scalp, forehead, cheeks, teeth, or jaw and side of the face.

TN is not easily controlled but can be managed with a variety of treatment options.[9]

Signs and symptoms

This disorder is characterized by episodes of intense facial pain that last from a few seconds to several minutes or hours. The episodes of intense pain may occur paroxysmally. To describe the pain sensation, patients may describe a trigger area on the face so sensitive that touching or even air currents can trigger an episode; however, in many patients the pain is generated spontaneously without any apparent stimulation. It affects lifestyle as it can be triggered by common activities such as eating, talking, shaving and brushing teeth. Wind, high pitched sounds, loud noises such as concerts or crowds, chewing, and talking can aggravate the condition in many patients. The attacks are said by those affected to feel like stabbing electric shocks, burning, pressing, crushing, exploding or shooting pain that becomes intractable.

Individual attacks usually affect one side of the face at a time, lasting from several seconds to a few minutes and repeat up to hundreds of times throughout the day. The pain also tends to occur in cycles with remissions lasting months or even years. 10-12% of cases are bilateral, or occurring on both sides. This normally indicates problems with both trigeminal nerves since one serves strictly the left side of the face and the other serves the right side. Pain attacks are known to worsen in frequency or severity over time, in some patients. Many patients develop the pain in one branch, then over years the pain will travel through the other nerve branches. Some patients also experience pain in the index finger.[10]

It may slowly spread to involve more extensive portions of the trigeminal nerve. The spread may even affect all divisions of the nerve, and sometimes simultaneously. Cases with bilateral involvement have not indicated simultaneous activity. The following suggest a systemic development: rapid spreading, bilateral involvement, or simultaneous participation with other major nerve trunks. Examples of systemic involvement include multiple sclerosis or expanding cranial tumor. Examples of simultaneous involvement include tic convulsive (of the fifth and seventh cranial nerves) and occurrence of symptoms in the fifth and ninth cranial nerve areas.[11]

Outwardly visible signs of TN can sometimes be seen in males who may deliberately miss an area of their face when shaving, in order to avoid triggering an episode. Successive recurrences are incapacitating and the dread of provoking an attack may make sufferers unable to engage in normal daily activities.

There is also a variant of TN called atypical trigeminal neuralgia (also referred to as "trigeminal neuralgia, type 2"),[12] based on a recent classification of facial pain.[13] In some cases of atypical TN the sufferer experiences a severe, relentless underlying pain similar to a migraine in addition to the stabbing shock-like pains. In other cases, the pain is stabbing and intense but may feel like burning or prickling, rather than a shock. Sometimes the pain is a combination of shock-like sensations, migraine-like pain, and burning or prickling pain. It can also manifest as an unrelenting, boring, piercing pain.

Causes

The trigeminal nerve is a mixed cranial nerve responsible for sensory data such as tactition (pressure), thermoception (temperature), and nociception (pain) originating from the face above the jawline; it is also responsible for the motor function of the muscles of mastication, the muscles involved in chewing but not facial expression.

Several theories exist to explain the possible causes of this pain syndrome. It was once believed that the nerve was compressed in the opening from the inside to the outside of the skull; but newer leading research indicates that it is an enlarged blood vessel - possibly the superior cerebellar artery - compressing or throbbing against the microvasculature of the trigeminal nerve near its connection with the pons. Such a compression can injure the nerve's protective myelin sheath and cause erratic and hyperactive functioning of the nerve. This can lead to pain attacks at the slightest stimulation of any area served by the nerve as well as hinder the nerve's ability to shut off the pain signals after the stimulation ends. This type of injury may rarely be caused by an aneurysm (an outpouching of a blood vessel); by an AVM (arteriovenous malformation);[14] by a tumor; by an arachnoid cyst in the cerebellopontine angle;[15] or by a traumatic event such as a car accident.

Short-term peripheral compression is often painless, with pain attacks lasting no more than a few seconds.[6] Persistent compression results in local demyelination with no loss of axon potential continuity. Chronic nerve entrapment results in demyelination primarily, with progressive axonal degeneration subsequently.[6] It is, "therefore widely accepted that trigeminal neuralgia is associated with demyelination of axons in the Gasserian ganglion, the dorsal root, or both."[16] It has been suggested that this compression may be related to an aberrant branch of the superior cerebellar artery that lies on the trigeminal nerve.[16] Further causes, besides an aneurysm, multiple sclerosis or cerebellopontine angle tumor, include: a posterior fossa tumor, any other expanding lesion or even brainstem diseases from strokes.[16]

Trigeminal Neuralgia is found in 3-4% of people with Multiple Sclerosis, according to data from seven studies.[17] Only two to four percent of patients with TN,[citation needed] usually younger,[citation needed] have evidence of multiple sclerosis, which may damage either the trigeminal nerve or other related parts of the brain. It has been theorized that this is due to damage to the spinal trigeminal complex.[18] Trigeminal pain has a similar presentation in patients with and without MS.[19]

Postherpetic neuralgia, which occurs after shingles, may cause similar symptoms if the trigeminal nerve is damaged.

When there is no [apparent] structural cause, the syndrome is called idiopathic.

Management

As with many conditions without clear physical or laboratory diagnosis, TN is sometimes misdiagnosed. A TN sufferer will sometimes seek the help of numerous clinicians before a firm diagnosis is made.

There is evidence that points towards the need to quickly treat and diagnose TN. It is thought that the longer a patient suffers from TN, the harder it may be to reverse the neural pathways associated with the pain.

The differential diagnosis includes temporomandibular disorder.[20] Since triggering may be caused by movements of the tongue or facial muscles, TN must be differentiated from masticatory pain that has the clinical characteristics of deep somatic rather than neuropathic pain. Masticatory pain will not be arrested by a conventional mandibular local anesthetic block.[11]

Dentists who suspect TN should proceed in the most conservative manner possible and should ensure that all tooth structures are "truly" compromised before performing extractions or other procedures.[medical citation needed]

Medical

- The anticonvulsant carbamazepine is the first line treatment; second line medications include baclofen, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, gabapentin, pregabalin, and sodium valproate. Uncontrolled trials have suggested that clonazepam and lidocaine may be effective.[21]

- Low doses of some antidepressants such as amitriptyline are thought to be effective in treating neuropathic pain, but a tremendous amount of controversy exists on this topic,[citation needed] and their use is often limited to treating the depression that is associated with chronic pain, rather than the actual sensation of pain from the trigeminal nerve.[citation needed] Antidepressants are also used to counteract a medication side effect.

- Duloxetine can also be used in some cases of neuropathic pain, and as it is also an antidepressant can be particularly helpful where neuropathic pain and depression are combined.[22]

- Opiates such as morphine and oxycodone can be prescribed, and there is evidence of their effectiveness on neuropathic pain, especially if combined with gabapentin.[23][24]

- Gallium maltolate in a cream or ointment base has been reported to relieve refractory postherpetic trigeminal neuralgia.[25]

Surgical

The evidence for surgical therapy is poor[26] and it is thus only recommended if medical treatment is not effective.[27] While there may be pain relief there is also frequently numbness post procedure.[26] Microvascular decompression appears to result in the longest pain relief.[26] Percutaneous radiofrequency thermorhizotomy may also be effective[28] as may gamma knife radiosurgery, however the effectiveness decreases with time.[29]

Three other procedures use needles or catheters that enter through the face into the opening where the nerve first splits into its three divisions. Some excellent success rates using a cost-effective percutaneous surgical procedure known as balloon compression have been reported.[30] This technique has been helpful in treating the elderly for whom surgery may not be an option due to coexisting health conditions. Balloon compression is also the best choice for patients who have ophthalmic nerve pain or have experienced recurrent pain after microvascular decompression.

Glycerol injections involve injecting an alcohol-like substance into the cavern that bathes the nerve near its junction. This liquid is corrosive to the nerve fibers and can mildly injure the nerve enough to hinder the errant pain signals. In a radiofrequency rhizotomy, the surgeon uses an electrode to heat the selected division or divisions of the nerve. Done well, this procedure can target the exact regions of the errant pain triggers and disable them with minimal numbness.

History, society and culture

TN has been called "suicide disease" in the past.[31][32] Some example cases of TN include:

- Entrepreneur and author Melissa Seymour was diagnosed with TN in 2009 and underwent microvascular decompression surgery in a well documented case covered by magazines and newspapers which helped to raise public awareness of the illness in Australia. Seymour was subsequently made a Patron of the Trigeminal Neuralgia Association of Australia.[33]

- American writer Truman Capote [34]

- In August 2011, Bollywood Star Salman Khan admitted he suffers from trigeminal neuralgia. In an interview, he said that he has been quietly suffering it for the past seven years, but now the pain has become unbearable. It has even affected his voice, making it much harsher.

See also

- Trigeminal trophic syndrome

- John Murray Carnochan

- James Ewing Mears

References

- ↑ Williams, Christopher; Dellon, A.; Rosson, Gedge (5 March 2009). "Management of Chronic Facial Pain". Craniomaxillofacial Trauma and Reconstruction 2 (02): 067–076. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1202593. PMC 3052669. PMID 22110799.

- ↑ "Facial Neuralgia Resources". Trigeminal Neuralgia Resources / Facial Neuralgia Resources. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ↑ Hackley, CE (1869). A text-book of practical medicine. D. Appleton & Co. p. 292. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- ↑ Bagheri, SC; et al (December 1, 2004). "Diagnosis and treatment of patients with trigeminal neuralgia". Journal of the American Dental Association 135 (12): 1713–7. PMID 15646605. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- ↑ Rapini, RP.; Bolognia, JL.; Jorizzo, JL (2007). Dermatology. 1 and 2. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 101. ISBN 1-4160-2999-0.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Okeson, JP (2005). "6". In Lindsay Harmon. Bell's orofacial pains: the clinical management of orofacial pain. Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc. p. 114. ISBN 0-86715-439-X.

- ↑ Bloom, R. "Emily Garland: A young girl's painful problem took more than a year to diagnose".

- ↑ Trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm by UF&Shands - The University of Florida Health System. Retrieved Mars 2012

- ↑ Satta Sarmah (2008). "Nerve disorder's pain so bad it's called the 'suicide disease'". Medill Reports Chicago. http://news.medill.northwestern.edu/chicago/news.aspx?id=79817

- ↑ Bayer DB, Stenger TG (1979). "Trigeminal neuralgia: an overview". Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 48 (5): 393–9. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(79)90064-1. PMID 226915.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Okeson, JP (2005). "17". In Lindsay Harmon. Bell's orofacial pains: the clinical management of orofacial pain. Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc. p. 453. ISBN 0-86715-439-X.

- ↑ "Neurological surgery: facial pain". Oregon Health & Science University. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- ↑ Burchiel KJ (2003). "A new classification for facial pain". Neurosurgery 53 (5): 1164–7. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000088806.11659.D8. PMID 14580284.

- ↑ Singh N, Bharatha A, O’Kelly C, Wallace MC, Goldstein W, Willinsky RA, Aviv RI, Symons SP. Intrinsic arteriovenous malformation of the trigeminal nerve. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2010 September; 37(5):681-683.

- ↑ Babu R, Murali R (1991). "Arachnoid cyst of the cerebellopontine angle manifesting as contralateral trigeminal neuralgia: case report". Neurosurgery 28 (6): 886–7. doi:10.1097/00006123-199106000-00018. PMID 2067614.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Okeson, JP (2005). "6". In Lindsay Harmon. Bell's orofacial pains: the clinical management of orofacial pain. Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc. p. 115. ISBN 0-86715-439-X.

- ↑ Foley P, Vesterinen H, Laird B et al (2013). "Prevalence and natural history of pain in adults with multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Pain 154 (5): 632–42. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2012.12.002.

- ↑ Cruccu G, Biasiotta A, Di Rezze S et al. (2009). "Trigeminal neuralgia and pain related to multiple sclerosis". Pain 143 (3): 186–91. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.12.026. PMID 19171430.

- ↑ De Simone R, Marano E, Brescia MV et al. (2005). "A clinical comparison of trigeminal neuralgic pain in patients with and without underlying multiple sclerosis". Neurol Sci. 26 Suppl 2: s150–1. doi:10.1007/s10072-005-0431-8. PMID 15926016.

- ↑ Drangsholt, M; Truelove, EL (2001). "Trigeminal neuralgia mistaken as temporomandibular disorder". J Evid Base Dent Pract 1 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1067/med.2001.116846.

- ↑ Sindrup, SH; Jensen, TS (2002). "Pharmacotherapy of trigeminal neuralgia". Clin J Pain 18 (1): 22–7. doi:10.1097/00002508-200201000-00004. PMID 11803299.

- ↑ Lunn, MPT; Hughes, R.A.C; Wiffen, P.J (7 October 2009). "Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy or chronic pain". In Lunn, MPT. Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy or chronic pain. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007115.pub2. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- ↑ "Science Links Japan | Trigeminal Neuralgia-A View of Opioid Treatment". Sciencelinks.jp. 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ↑ "news item - Morphine plus gabapentin better combined than separate in neuropathic pain". Ukmicentral.nhs.uk. 2005-03-31. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ↑ Bernstein, L.R. (2012). "Successful treatment of refractory postherpetic neuralgia with topical gallium maltolate: case report". Pain Medicine 13: 915–918. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01404.x. PMID 22680305.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Zakrzewska, JM; Akram, H (Sep 7, 2011). "Neurosurgical interventions for the treatment of classical trigeminal neuralgia.". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 9: CD007312. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007312.pub2. PMID 21901707.

- ↑ Sindou, M; Keravel, Y (April 2009). "[Algorithms for neurosurgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia].". Neuro-Chirurgie 55 (2): 223–5. doi:10.1016/j.neuchi.2009.02.007. PMID 19328505.

- ↑ Sindou, M; Tatli, M (April 2009). "[Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia with thermorhizotomy].". Neuro-Chirurgie 55 (2): 203–10. doi:10.1016/j.neuchi.2009.01.015. PMID 19303114.

- ↑ Dhople, AA; Adams, JR, Maggio, WW, Naqvi, SA, Regine, WF, Kwok, Y (August 2009). "Long-term outcomes of Gamma Knife radiosurgery for classic trigeminal neuralgia: implications of treatment and critical review of the literature. Clinical article.". Journal of neurosurgery 111 (2): 351–8. doi:10.3171/2009.2.JNS08977. PMID 19326987.

- ↑ Natarajan, M (2000). "Percutaneous trigeminal ganglion balloon compression: experience in 40 patients". Neurology (Neurological Society of India) 48 (4): 330–2. PMID 11146595.

- ↑ Adams, H; Pendleton, C; Latimer, K; Cohen-Gadol, AA; Carson, BS; Quinones-Hinojosa, A (2011 May). "Harvey Cushing's case series of trigeminal neuralgia at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: a surgeon's quest to advance the treatment of the 'suicide disease'.". Acta neurochirurgica 153 (5): 1043–50. PMID 21409517.

- ↑ Prasad, S; Galetta, S (2009). "Trigeminal Neuralgia Historical Notes and Current Concept". Neurologist 15 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181775ac3. PMID 19276786. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- ↑ "Melissa Seymour: My perfect life is over". Womansday.ninemsn.com.au. 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ↑ Albin Krebs (1984-08-28). "Truman Capote Is Dead at 59; Novelist of Style and Clarity". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-12-17.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||