Tricubic interpolation

given values at the blue corner points.

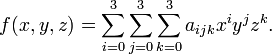

given values at the blue corner points.In the mathematical subfield numerical analysis, tricubic interpolation is a method for obtaining values at arbitrary points in 3D space of a function defined on a regular grid. The approach involves approximating the function locally by an expression of the form

This form has 64 coefficients  ; requiring the function to have a given value or given directional derivative at a point places one linear constraint on the 64 coefficients.

; requiring the function to have a given value or given directional derivative at a point places one linear constraint on the 64 coefficients.

The term tricubic interpolation is used in more than one context; some experiments measure both the value of a function and its spatial derivatives, and it is desirable to interpolate preserving the values and the measured derivatives at the grid points. Those provide 32 constraints on the coefficients, and another 32 constraints can be provided by requiring smoothness of higher derivatives.[1]

In other contexts, we can obtain the 64 coefficients by considering a 3x3x3 grid of small cubes surrounding the cube inside which we evaluate the function, and fitting the function at the 64 points on the corners of this grid.

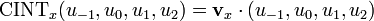

The cubic interpolation article indicates that the method is equivalent to a sequential application of one dimensional cubic interpolators. Let  be the value of a monovariable cubic polynomial (e.g. constrained by values,

be the value of a monovariable cubic polynomial (e.g. constrained by values,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  from consecutive grid points) evaluated at

from consecutive grid points) evaluated at  . In many useful cases, these cubic polynomials have the form

. In many useful cases, these cubic polynomials have the form  for some vector

for some vector  which is a function of

which is a function of  alone. The tricubic interpolator is equivalent to

alone. The tricubic interpolator is equivalent to

where  and

and ![x,y,z\in [0,1]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/3/5/c/5/35c5e46f5c88b31ea3d57bf662a3321d.png) .

.

At first glance, it might seem more convenient to use the 21 calls to  described above instead of the

described above instead of the  matrix described in Lekien and Marsden.[2] However, a proper implementation using a sparse format for the matrix (that is fairly sparse) makes the latter more efficient. This aspect is even much more pronounced when interpolation is needed at several locations inside the same cube. In this case, the

matrix described in Lekien and Marsden.[2] However, a proper implementation using a sparse format for the matrix (that is fairly sparse) makes the latter more efficient. This aspect is even much more pronounced when interpolation is needed at several locations inside the same cube. In this case, the  matrix is used once to compute the interpolation coefficients for the entire cube. The coefficients are then stored and used for interpolation at any location inside the cube. In comparison, sequential use of one-dimensional integrators

matrix is used once to compute the interpolation coefficients for the entire cube. The coefficients are then stored and used for interpolation at any location inside the cube. In comparison, sequential use of one-dimensional integrators  performs extremely poorly for repeated interpolations because each computational step must be repeated for each new location.

performs extremely poorly for repeated interpolations because each computational step must be repeated for each new location.

See also

- Cubic interpolation

- Bicubic interpolation

- Trilinear interpolation

References

- ↑ Tricubic Interpolation in Three Dimensions (2005), by F. Lekien, J. Marsden, Journal of Numerical Methods and Engineering

- ↑ Tricubic Interpolation in Three Dimensions (2005), by F. Lekien, J. Marsden, Journal of Numerical Methods and Engineering

External links

- Java/C++ implementation of tricubic interpolation

- C++ implementation of tricubic interpolation

- Python implementation