Trial division

Trial division is the most laborious but easiest to understand of the integer factorization algorithms. The essential ideal behind trial division tests to see if an integer n, the integer to be factored, can be divided by each number in turn that is less than n. For example, for the integer n = 12, the only numbers that divide it are 1,2,3,4,6,12. Selecting only the largest powers of primes in this list gives that 12 = 3 × 4.

Method

Given an integer n (throughout this article, n refers to "the integer to be factored"), trial division consists of systematically testing whether n is divisible by any smaller number. Clearly, it is only worthwhile to test candidate factors less than n, and in order from two upwards because an arbitrary n is more likely to be divisible by two than by three, and so on. With this ordering, there is no point in testing for divisibility by four if the number has already been determined not divisible by two, and so on for three and any multiple of three, etc. Therefore, effort can be reduced by selecting only prime numbers as candidate factors. Furthermore, the trial factors need go no further than  because, if n is divisible by some number p, then n = p×q and if q were smaller than p, n would have earlier been detected as being divisible by q or a prime factor of q.

because, if n is divisible by some number p, then n = p×q and if q were smaller than p, n would have earlier been detected as being divisible by q or a prime factor of q.

A definite bound on the prime factors is possible. Suppose Pi is the i'th prime, so that P1 = 2, P2 = 3, P3 = 5, etc. Then the last prime number worth testing as a possible factor of n is Pi where P2i + 1 > n; equality here would mean that Pi + 1 is a factor. Thus, testing with 2, 3, and 5 suffices up to n = 48 not just 25 because the square of the next prime is 49, and below n = 25 just 2 and 3 are sufficient. Should the square root of n be integral, then it is a factor and n is a perfect square.

An example of the trial division algorithm, using a prime sieve for prime number generation, is as follows (in Python):

def trial_division(n): """Return a list of the prime factors for a natural number.""" if n == 1: return [1] primes = prime_sieve(int(n**0.5) + 1) prime_factors = [] for p in primes: if p*p > n: break while n % p == 0: prime_factors.append(p) n /= p if n > 1: prime_factors.append(n) return prime_factors

Trial division is guaranteed to find a factor of n if there is one, since it checks all possible prime factors of n. Thus, if the algorithm finds one factor, n, it is proof that n is a prime. If more than one factor is found, then n is a composite integer. A more computationally advantageous way of saying this is, if any prime whose square does not exceed n divides it without a remainder, then n is not prime.

Speed

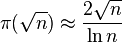

In the worst case, trial division is a laborious algorithm. If it starts from two and works up to the square root of n, the algorithm requires

trial divisions, where  denotes the prime-counting function, the number of primes less than x. This does not take into account the overhead of primality testing to obtain the prime numbers as candidate factors. A useful table need not be large: P(3512) = 32749, the last prime that fits into a sixteen-bit signed integer and P(6542) = 65521 for unsigned sixteen-bit integers. That would suffice to test primality for numbers up to 655372 = 4,295,098,369. Preparing such a table (usually via the Sieve of Eratosthenes) would only be worthwhile if many numbers were to be tested. If instead a variant is used without primality testing, but simply dividing by every odd number less than the square root of n, prime or not, it can take up to about

denotes the prime-counting function, the number of primes less than x. This does not take into account the overhead of primality testing to obtain the prime numbers as candidate factors. A useful table need not be large: P(3512) = 32749, the last prime that fits into a sixteen-bit signed integer and P(6542) = 65521 for unsigned sixteen-bit integers. That would suffice to test primality for numbers up to 655372 = 4,295,098,369. Preparing such a table (usually via the Sieve of Eratosthenes) would only be worthwhile if many numbers were to be tested. If instead a variant is used without primality testing, but simply dividing by every odd number less than the square root of n, prime or not, it can take up to about

trial divisions, which for large n is worse.

Even so, this is a quite satisfactory method. Difficulty arises only when large numbers are being considered. Typical talk is not of n but of the number of bits in n, such as 1024. Thus, n is a number around 21024 which is about 10308 so that factors up to about 10154 would have to be tested, and even if only prime numbers were to be considered as factors, there are about 10151 candidates. Further, because such large numbers far exceed the integer sizes of typical computers, arbitrary precision arithmetic techniques are required, at an enormous cost in time for each trial division. Thus in public key cryptography, values for n, chosen to have large prime factors of similar size, cannot be factored by any publicly known method in a useful time period on any available computer system or collective. Suppose that 1010 computers could be set to the task (more than one per person on the entire globe), and that each could perform 1010 trial divisions a second (well beyond current abilities); the collective could eliminate 1020 factors a second. Then only 10134 seconds (about 10126 years) would be required to exhaust all candidates.

However, for n with at least one small factor, trial division can be a quick way to find that small factor. For n chosen uniformly at random from integers of a given length, there is a 50% chance that 2 is a factor of n, and a 33% chance that 3 is a factor, and so on. It can be shown that 88% of all positive integers have a factor under 100, and that 92% have a factor under 1000. Thus, when confronted by an arbitrary large n, it is worthwhile to check for divisibility by the small primes. With a binary (or decimal) representation, it should be immediately apparent whether the number is divisible by two, for example.

For most significant factoring concerns, however, other algorithms are more efficient and therefore feasible.

References

- Childs, Lindsay N. (2009). A concrete introduction to higher algebra. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-74527-5. Zbl 1165.00002.

- Crandall, Richard; Pomerance, Carl (2005). Prime numbers. A computational perspective (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-25282-7. Zbl 1088.11001.

External links

- Javascript Prime Factor Calculator using trial division. Can handle numbers up to about 9×1015

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||