Trams in Vienna

| Vienna tramway network | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type B and E1 trams at Schwedenplatz. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Vienna, Austria | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 48°12′29.40″N 16°22′21.13″E / 48.2081667°N 16.3725361°E

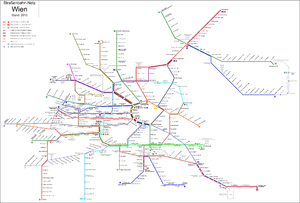

The Vienna tramway network (German: Wiener Straßenbahn-Netz) is a vital part of the public transport system in Vienna, capital city of Austria. In operation since 1865, the network reached its greatest extent during the interwar period (1918–1939). Today, it is still one of world's largest tram networks, at about 180 km (112 mi) in total length and 1031 stations.

The trams on the network run on standard gauge track. Since 1897, they have been powered by electricity, at 600 V DC. The current operator of the network is Wiener Linien. In 2009, a total of 186.9 million passengers used the network's trams. As of January 2013, the number of trams or tramsets scheduled in service in peak periods was 404, comprising 215 single cars and 189 motor+trailer sets.[1]

History

Horsecar tramways

The earliest precursor of the Vienna tramway network was the Brigittenauer Eisenbahn, a horsecar tramway. From 1840 to 1842, it led from the Donaukanal to the recreational establishment known as the Kolosseum, at the end of the Jägerstraße.

Some two decades later, several firms competed for a concession to construct an urban "horse-tramway" in Vienna. Schaeck-Jaquet & Comp prevailed. By October 1865, trams could be recorded as operating between Schottentor and Hernals, and on 24 April 1866, the route was extended to Dornbach.

Subsequently, the municipality of Vienna tried to persuade other firms to construct tramway lines. However, due to the difficult conditions, all of the competing firms (including Schaeck-Jaquet & Comp) arranged a merger, leaving the newly formed Wiener Tramwaygesellschaft as the only remaining firm. In later years, that firm built the majority of the Vienna tramway network. The social conditions were nevertheless such that labour disputes arose. In 1872, the Neue Wiener Tramwaygesellschaft was formed as a competitor, but initially was able to build only a network in the suburbs.

The steam tramways

In 1883, the Dampftramway Krauss & Comp. opened Vienna's first steam tramway line, between Hietzing and Perchtoldsdorf. In 1887, the line was extended further south to Mödling, and towards the city centre to Gaudenzdorf, and a new branch line led to Ober St. Veit. A further line, of national significance, was opened in 1886 from Donaukanal to Stammersdorf, where the trams connected with trains on the Stammersdorfer Lokalbahn to Auersthal. From Floridsdorf a branch line led to Groß Enzersdorf.

Alongside the Dampftramway Krauss & Comp., the Neue Wiener Tramwaygesellschaft also operated a few lines with steam locomotives.

Early electric tramways

At the turn of the century, Vienna's Bürgermeister Karl Lueger began the municipalization of urban services, which, until then, had been supplied by private enterprises. In 1899, by a proclamation issued by Minister Heinrich von Wittek, the municipality received a 90 year concession from the Imperial Railway Ministry for "a network of standard gauge light railway lines in Vienna to be operated by electric power". The 99 lines (or sections) explicitly identified in the proclamation included new lines, and the purchase of the network of the Wiener Tramwaygesellschaft, the employees of which were to be taken on as far as possible by the city. The lines were integrated into the Gemeinde Wien – Städtische Straßenbahnen service, which was entered on 4 April 1902 into the company register. In 1903, the network of the Neue Wiener Tramwaygesellschaft was also purchased.

On 28 January 1897, an electric tram operated for the first time in Vienna: on the tracks of today's line 5. With their lower noise and odour production compared with horse-drawn and steam tramways, the electric trams quickly became favourites. On 26 June 1903, the last horse tramway was ceremoniously farewelled. In 1907 the line designations still valid today, using numbers and letters, were introduced. The steam tramway was able to continue operating its services until 1922 on a few branch lines in the outer suburbs. Well into the second half of the twentieth century, Viennese frequently referred to the electrified tramway as die Elektrische (the electric).

Up until 1910, the only trams delivered to the Vienna tramway network were vehicles with unglazed platforms (or cabs), i.e.: without any windscreens protecting occupants from the cold and wind. This was still in the tradition of the horse cars, on which direct contact of the driver with the harnessed horses was required. (It took until 1930 until the cabs and platforms of all tramcars had protective glass.) In 1911, the first double stops were introduced.

During World War I, tram operations were increasingly difficult to perform. From 1916, women had to take over part of the work of the male tramway staff engaged by the military. Due to the harsh conditions of that time, operations had to be partially closed down. In 1917, a quarter of all stops were abandoned.

On 16 October 1925, the Wiener Stadtbahn, which had been taken over by the municipality of Vienna, was absorbed into the tramway network's tariff system. In 1929, the peak tram fleet was achieved, and in 1930 the network reached its maximum length, 318 km (198 mi). In the interwar period, Vienna had more people than today. In 1910, the city reached 2.1 million; after First World I began, the population decreased significantly, reaching its lowest level at the time of the 1991 census, at about half a million. Between the wars, the tramway was virtually unrivalled as a city transport in Vienna.

After the Anschluss with Germany's Third Reich, the tramway network was changed on 19 September 1938 from left hand traffic to right hand traffic. During World War II, tram operations continued, for as long as Vienna remained spared from fighting. Its peak haulage, on the then still extensive route network, was almost 732 million passengers, in 1943. That year, 18,000 people found work on Vienna's tramways.

In 1944-1945, however, when Vienna was bombed extensively, operations had to be gradually closed down, until the last line, the O-Line, was closed on 7 April 1945.

After World War II

Following the Battle of Vienna in early April 1945, the first five lines were able to be returned to service on 28 April. Most of the city's fleet of 4000 trams were badly damaged, 400 of them beyond repair. The task of restoring the network would not be completed until 1950; some short sections of track were never put back into operation.

In 1948, Vienna acquired second hand trams of Type Z (road numbers 4201-4242) under the Marshall Plan from New York. These trams, which became known as Amerikaner (Americans), were a little wider than other trams used in Vienna. They could only be put into operation on tracks that had a wider track spacing, left over from the steam tramways. An example of these more widely spaced tracks was Line 331 to Stammersdorf. The Amerikaner were comparatively modern, because they were equipped with air-operated doors and automatic retractable ramps. Additionally, the seat backs could be adjusted, so that all seated passengers could always face towards the direction of travel. Some of the major modifications required for the Amerikaner to be able to run in Vienna were carried out by Gräf & Stift in Wien-Liesing.

Until the 1950s, the network was still consistently operated with old, repaired and partially rebuilt trams, as new ones could be purchased only from 1951 onwards. Even in the 1950s, new trams were consistently obtained in series of only limited numbers, as from 1955 the abolition of the tramway in Vienna was the contemporary transport planning vision, and investments were made accordingly.

In their early to mid-20th century, private cars had been the exception in European cities, because they had then been too expensive for most of the population. However, with the growth of private transport in the postwar period, the calls for a car-friendly city became louder. Rail traffic on the road was therefore seen as a "transport barrier" (the term "transport" applying only to motor vehicles), and the full relocation of public transport to the U-Bahn and buses was seen as the vision of the future.

In 1956, Vienna's first articulated trams, designated as Type D, were commissioned from Gräf & Stift. Due to the tight financial situation, the new trams were assembled from salvaged parts. The basis of each one was two old Stadtbahn trailer chassis, on which modern car bodies were mounted. The chassis and bodies were then connected, by means of a telescopic joint section, of Italian design. The prototype of the Type D, with road number 4301, was delivered on 3 July 1957. After the testing and commissioning process had been completed, the Type D entered service from 17 February 1958. The inaugural trip operated by these trams was on Line 71.

A total of 16 type D trams were built. They were used until 1976 on Lines 9, 41, 42 and E2. They were cumbersome, due to their high weight (28 t (31 short tons; 28 long tons)), and were also otherwise unconvincing.

Changes, new trams, U-Bahn construction

In 1958, at the time of conversion of the short Line 158, the practicality of using buses to replace trams was tested. From 1960, there was ongoing conversion of sections of track running through narrow streets in the densely built up areas within the Gürtel; the best known example is line 13 from Wien Südbahnhof to Alserstrasse. However, individual sections on the periphery of the city, and in surrounding communities beyond the city limits, such as the former steam tramway lines to Mödling and Groß-Enzersdorf, were replaced by bus lines.

The realisation that the contemplated abolition of the tramway would not be a short-term project, mainly because of the rather lengthy construction of the planned U-Bahn network, led to the introduction, from 1959, of the six-axle articulated type E and E1 trams, of which a total of 427 were built to 1976. This was a generational change of long term effect.

The last high-floor articulated trams to enter the fleet were the Type E2 vehicles, which were built under licence from DUEWAG, together with matching type c5 trailer cars; they entered service on 28 August 1978 on Line 6, and remain in service today. This type was the first to be fitted with exits featuring retractable steps to improve comfort when entering and alighting. Additionally, the tramcar design was moderized, and the safety features of the technical equipment were considerably improved. A total 98 cars of this type were produced by Simmering-Graz-Pauker, and 24 by Bombardier.

The construction of the Vienna U-Bahn led to further extensive line closures in the tramway network, due to a policy that trams are not to operate in parallel with the U-Bahn, even on short sections. As this policy is still in effect today, further closures of tramway lines can be expected, to coincide with the further expansion of the U-Bahn network. However, the continued existence of the tramway network in Vienna is no longer in question, and there are even some new openings planned.

For reasons of economy, Wiener Linien ceased to roster conductors in trailer cars from 1964, and in powered cars from 1972. Industrial relations factors delayed the final departure of conductors until 1996, when the last conductor ended his service (on Line 46).

Fleet

The Vienna tram fleet presently consists of high-floor trams and low-floor trams, the so-called ULFs.

As of 2011, lines 30 and 33 were operated exclusively by high-floor trams. Conversion of line 18 to operation by low-floor trams was completed at the start of July 2010. For 2011, low-floor trams were set to take over on line 33.

All other lines are presently operated alternately by high- and low-floor vehicles.

High-floor trams

From 1959, articulated tramcars of Type E were introduced to the Vienna tram network. However, these trams could be operated with trailer cars only with great difficulty, due to their underpowered motors. In view of this problem, it became necessary to order a successor type soon afterwards.

The successors, the Type E1 trams, were first delivered in 1966. They were of similar appearance to their predecessors, but equipped with more powerful motors. The Type E remained in service until 2007, most recently on lines 10 and 62.

After production of the E1 ceased in 1976, a further successor generation, the Type E2, was developed. That type has been in service since 1978. As of 2011, the Type E1 trams were the most numerous vehicle type on the Vienna tramway network. They operate scheduled services on 21 of the 28 lines.

The trailer fleet constructed to match the tramcars is made up of Types c3 and c4 for the E1 tramcars, and Type c5 for E2 tramcars. On the less frequented lines, tramcars also operate without trailers.

Following a number of serious accidents, the majority of the high-floor trams have been fitted with electric door edge sensors and mirrors.[2]

Tramcars

- Type E1 – 184 cars (originally 338) – built 1966–1976; seats: 40, standing places: 65.

- Type E2 – 121 cars (originally 122) – built 1978–1990; seats: 44, standing places: 58.

Trailers

- Type c3 – 61 cars (originally 190) – built 1959–1962; seats: 32, standing places: 43.

- Type c4 – 73 cars – built 1974–1977; seats: 31, standing places: 43.

- Type c5 – 117 cars – built 1978–1990; seats: 32, standing places: 39.

-

_(Wieden%2C_Vienna_-_2002).jpg)

Type E – in service to 2007.

-

Tramcar E1 + Trailer c4.

-

Type E2+c5.

-

Vienna Ring Tram Type E1.

Low-floor trams

There are two low-floor vehicle types in Vienna: Type A, a short version with five segments, and Type B, a longer, seven-unit version.

Beginning in 1995, one prototype of each of these types operated on the network. Since 1997, series production versions of both types have been in service.

Type A1, a further development of Type A, is the first generation of Vienna tramcars to be fitted with air conditioning. This type has been in service since 2007, and is currently used on lines 9, 10, 46, 52, 58 and 62. Deliveries of the longer ULF version, the Type B1, began in April 2009, and that type is presently in service on lines D, 38 and 43.

After a fire in one of the low-floor trams in July 2009, it was decided to retrofit all of them with special fenders.[3]

Tramcars

- Type A – 51 cars – built 1995–2006; seats: 42, standing places: 94.

- Type B – 101 cars – built 1995–2005; seats: 66, standing places: 141.

- Type A1 – 40 cars delivered, 80 cars on order – built 2006–present; seats: 42, standing places: 94.

- Type B1 – 67 cars delivered, 70 cars on order – built 2009–present; seats: 66, standing places: 143.

-

Type A low-floor tram.

-

Type B ULF.

-

Heritage tram and Type A1.

-

Type B1 at Hernals station.

Depots

Throughout its history, the Vienna tramway network has had a variety of Remisen ("carriage houses"), which were officially described as depots or stations. Due to the abandonment of numerous lines, some of these facilities have now been closed for trams (e.g. 2., Vorgartenstraße, 3., Erdberg, 12., Assmayergasse, 14., Breitensee, 15., Linke Wienzeile, 18., Währing, 22., Kagran). A few of them have nevertheless remained in use as operating garages for buses. In 2006, the now former Breitensee depot became the most recently abandoned facility, with its tram fleet being taken over by the Rudolfsheim station.

In recent years, as part of conservation measures, some depots have been gradually closed down as a separate unit, demoted to the status of so-called Abstellanlagen ("parking facilities"), and placed under a different depot. Currently, there are four operating depots in the Vienna tramway network and six parking facilities, as well as the Erdberg station, where the Vienna Tram Museum is housed. Repair work is now performed mostly in the remaining depots, where all vehicles are now officially stationed.

Certain Lines or vehicles are assigned to each depot or parking facility:

| Name | Symbol | Lines | Vehicles | Address | Nearest stop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favoriten depot | FAV | D, O, 1, 6, 18, 67, 71, VRT | A, B, E1, E2, c3, c5 | 10., Gudrunstraße 153 | Quellenplatz |

| Simmering parking facility |

SIM | 6, 71 | B, E1, E2, c3, c5 | 11., Simmeringer Hauptstraße 156 | Fickeysstraße |

| Floridsdorf depot | FLOR | 2, 5, 26, 30, 31, 33 | B, E1, c3, c4 | 21., Gerichtsgasse 5 | Floridsdorfer Markt |

| Brigittenau parking facility |

BRG | 2, 5, 33 | B, E1, c3, c4 | 20., Wexstraße 13 | Wexstraße |

| Kagran parking facility |

KAG | 26 | B, E1, c3, c4 | 22., Prandaugasse 11 | Kagran |

| Hernals depot | HLS | D, 1, 9, 37, 38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 | A, B, B1, E1, E2, c4, c5 | 17., Hernalser Hauptstraße 138 | Wattgasse |

| Gürtel parking facility |

GTL | D, 1, 37, 38, 40, 41, 42 | A, B, E1, E2, c4, c5 | 18., Währinger Gürtel 131 | Nußdorfer Straße |

| Rudolfsheim depot | RDH | 2, 5, 9, 10, 18, 46, 49, 52, 58, 60, 62 | A, A1, B, E1, E2, c3, c4, c5 | 15., Schwendergasse 51 | Anschützgasse |

| Ottakring parking facility |

OTG | 2, 10, 46, 49 | A, A1, B, E1, c3, c4 | 16., Joachimsthalerplatz 1 | Joachimsthalerplatz |

| Speising parking facility |

SPEIS | 10, 58, 60, 62 | A, A1, B, E1, E2, c3, c4, c5 | 13., Hetzendorfer Straße 188 | Wattmanngasse |

Heavier maintenance, along with periodic servicing, is performed in the Main Workshops of the Wiener Linien.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Tramways & Urban Transit magazine, April 2013, p. 147.

- ↑ Wiener Linien gehen auf Türfühlung

- ↑ Nach Brand werden alle ULFs nachgerüstet (ORF Wien, 31 July 2009)

Bibliography

- Kaiser, Wolfgang (2004). Die Wiener Straßenbahnen [The Vienna Tramways]. München: GeraMond. ISBN 3-7654-7189-5. (German)

- Krobot, Walter; Slezak, Josef Otto; Sternhart, Robert (1983). Straßenbahn in Wien: vorgestern und übermorgen [The Tramway in Vienna: before yesterday and beyond tomorrow] (2nd ed.). Wien: Verlag J. O. Slezak. ISBN 3-85416-076-3. (German)

- Lehnhart, Hans; Jeanmaire, Claude (1972). Die alten Wiener Tramways 1865-1945 [The Old Viennese Tramways (Austria)]. Villigen, Switzerland: Verlag Eisenbahn. ISBN 3856490159. (German)

- Pawlik, Hans Peter; Slezak, Josef Otto (1982). Wiener Straßenbahn Panorama [Vienna Tramway Panorama]. Wien: Verlag J. O. Slezak. ISBN 3900134804. (German)

- Pawlik, Hans Peter; Slezak, Josef Otto (1999). Ring-Rund: das Jahrhundert der elektrischen Strassenbahn in Wien [Ring-Round: the Century of the Electric Tramway in Vienna]. Wien: Verlag J. O. Slezak. ISBN 3-85416-187-5. (German)

- Schwandl, Robert (2006). Wien U-Bahn Album / Urban Rail in Vienna. Berlin: Robert Schwandl Verlag. ISBN 3-936573-14-X. (German) (English)

- Schwandl, Robert (2010). Schwandl's Tram Atlas Schweiz & Österreich. Berlin: Robert Schwandl Verlag. ISBN 978 3 936573 27 5. (German) (English)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trams in Vienna. |

- Timetable information & Route planner

- Die Pferdestraßenbahn (German) – with photos of horse and steam trams

- Die "Elektrische" - Die Entwicklung der Straßenbahn in Wien (German) – with photos of electric trams

- Tramway.at (German) – Viennese and international tramway website (with some English content)

- Wiener Tramwaymuseum – English summary page

- Vienna database / photo gallery and Vienna tram list at Urban Electric Transit – in various languages, including English.

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||