Traffic in Towns

Traffic in Towns was an influential report and popular book on urban and transport planning policy published 25th November 1963 for the UK Ministry of Transport by a team headed by the architect, civil engineer and planner Professor Sir Colin Buchanan.[1][2] The report warned of the potential damage caused by the motor car, while offering ways to mitigate it:[3]

It is impossible to spend any time on the study of the future of traffic in towns without at once being appalled by the magnitude of the emergency that is coming upon us. We are nourishing at immense cost a monster of great potential destructiveness, and yet we love him dearly. To refuse to accept the challenge it presents would be an act of defeatism.

It gave planners a set of policy blueprints to deal with its effects on the urban environment, including traffic containment and segregation, which could be balanced against urban redevelopment, new corridor and distribution roads and precincts.

These policies shaped the development of the urban landscape in the UK and some other countries for two or three decades. Unusually for a technical policy report, it was so much in demand that Penguin abridged it and republished it as a book in 1964.

Background

Buchanan's report was commissioned in 1960 by Ernest Marples, Transport Minister in Harold Macmillan's government, whose manifesto had promised to improve the existing road network and relieve congestion in the towns.[4]

Britain was still reconstructing itself after the devastation of World War II, and, although the economy was recovering, towns and cities still had large areas of bomb damage that needed rebuilding or re-use. New motorways were being planned and built across the country, and the motor car was already starting to fill up towns and villages. Wartime had seen the establishment of central planning, and the discipline of urban planning was looking for good patterns and policies to be implemented as they rebuilt.

Although the government was looking to manage motor vehicle growth, potentially with a congestion charge as suggested by the Smeed Report, this was contrasted by a strong desire for dramatic cost-saving measures in nationalised public transport. Doctor Beeching's proposed closure of a third of the passenger railway lines, the withdrawal of tramways and trolleybuses and shunning of light rail, with bus services offering a partial replacement, all emphasised the widely held expectation that "progress" would see an increasing dependency on private motor cars. This represented a departure from the previous policies set by the Salter Report of 1933, which looked to balance the needs of railways against motor vehicles.

Predictions

At the time of the report,[5] there were 10.5 million vehicles registered in Britain, but, at predicted growth rates, this number was expected to become 18 million by 1970, 27 million by 1980 and about 40 million vehicles in 2010, or 540 vehicles for every 1,000 population, equivalent to 1.3 cars per household. They expected growth in traffic to be uneven, with more congestion in South East England, and to incorporate a population that would reach 74 million.

The impact of the motor car was compared with that of a heavy goods vehicle which;

given its head, would wreck our towns within a decade... The problems of traffic are crowding in upon us with desperate urgency. Unless steps are taken, the motor vehicle will defeat its own utility and bring about a disastrous degradation of the surroundings for living... Either the utility of vehicles in town will decline rapidly, or the pleasantness and safety of surroundings will deteriorate catastrophically – in all probability both will happen.[5]

Indeed it can be said in advance that the measures required to deal with the full potential amount of motor traffic in big cities are so formidable that society will have to ask itself seriously how far it is prepared to go with the motor vehicle.[6]

There was a need to limit vehicle access to some urban areas:

Distasteful though we find the whole idea, we think that some deliberate limitation of the volume of motor traffic is quite unavoidable. The need for it just can't be escaped. Even when everything that it is possibly to do by way of building new roads and expanding public transport has been done, there would still be, in the absence of deliberate limitation, more cars trying to move into, or within our cities than could possibly be accommodated.[7]

Already the growth of vehicle ownership in America had not been held back by congestion in urban areas; they observed that congestion in Britain's smaller land mass might limit the use of cars but probably not affect people's desire for ownership as they became more affluent and hoped to try to use their cars. They saw the day coming when most adults would take the car "as much for granted as an overcoat", and value it as an "asset of the first order".

There would also be pressure to house a growing population and disperse more population away from overcrowded cities. However, dispersing the population around the countryside would be synonymous with urban sprawl, and would defeat one of the reasons for car ownership, to get out into the countryside. Having examined the road network in Los Angeles and Fort Worth, Buchanan wished to avoid their dehumanising effects and their creation of pedestrian "no-go" areas.[8] He also wished to ensure that the heritage within British towns was respected:

The American policy of providing motorways for commuters can succeed, even in American conditions, only if there is a disregard for all considerations other than the free flow of traffic which seems sometimes to be almost ruthless. Our British cities are not only packed with buildings, they are also packed with history and to drive motorways through them on the American scale would inevitably destroy much that ought to be preserved.[9]

The rise of traffic congestion would waste people's time, who would soon have to spend time sitting in traffic, in addition to their time spent in sleep, work, and leisure. Already, the average speed in many cities had fallen to 11 miles per hour (18 km/h), and congestion was costing the British economy £250 million in wasted man hours.

Yet the motor car was also inextricably linked to the economy, with 2,305,000 people working in the motor trade, or 10 percent of the labour force. It had already eclipsed the railway, and would become more prominent in the movement of goods and the workforce. The expansion of public transport would not provide an answer on its own.

However, the noise, fumes, pollution and visual intrusion of the cars and ugly traffic paraphernalia would overwhelm town centres, while vehicles parked on streets would force new hazards onto children at play.

Safety considerations should move to become foremost in the design of streets; three quarters of all injury accidents were occurring within towns (although most fatalities happened on open roads). They feared that future generations would think that they were careless and callous to mix people and moving vehicles on the same streets.

The report warned against trying to find a single "solution":

We have found it desirable to avoid the term 'solution' altogether for the traffic problem is not such much a problem waiting for a solution as a social situation requiring to be dealt with by policies patiently applied over a period and revised from time to time in light of events.[5]

Recommendations

The report[5] signified some fundamental shifts in attitudes to roads, by recognising that there were environmental disbenefits from traffic, and that large increases in capacity can exacerbate congestion problems, not solve them. This awareness of environmental impact was ahead of its time, and not translated into policy for some years in other countries, such as Germany or the USA, where the promotion of traffic flow remained paramount[10] The scale of traffic growth envisaged would soon overtake any benefits that small-scale road improvement would offer, which would anyway divert attention from the large-scale solutions that would be needed. These solutions would be very expensive and could only be justified if they were comprehensively planned, including social as well as traffic needs. However, the report saw no turning back from people's new-found dependence on the car, and thought that there would be limits to how much traffic could be transferred to railways and buses.

Towns should be worth living in, which meant more than just the ability to drive into the centre. Urban redevelopment should look to the long term, and avoid parsimonious short-termism. The report asked how bold the planners could be, when restricting access to town centres and controlling traffic flows:

It is a difficult and dangerous thing in a democracy to prevent a substantial part of the population from doing things they do not regard as wrong. ... The freedom with which a person can walk about and look around is a very useful guide to the civilized quality of an urban area ... judged against this standard, many of our towns now seem to leave a great deal to be desired ... there must be areas of good environment where people can live, work, shop, look about and move around on foot in reasonable freedom from the hazards of motor traffic.[5]

The report recommended that certain standards should always be met, including safety, visual intrusion, noise, and pollution limits. But if a city was both financially able and willing, it should rebuild itself with modern traffic in mind.

However, if circumstances meant that this was not possible it would have to restrain traffic, perhaps severely. This was revolutionary and ran counter to the wisdom of economists, who assumed that environmental standards could be set off against other considerations once they had been priced.[1]

Planners should set a policy regarding the character being sought for each urban area, and the level of traffic should then be managed to produced the desired effect, in a safe manner. This would result in towns with a lattice of environmentally planned areas joined by a road hierarchy, a network of distribution roads, with longer-distance traffic being directed around and away from these areas, rather like an interior would be designed with corridors serving a multitude of rooms.

It recommended the selective use of bypasses around small and medium-sized towns to alleviate congestion in the centres, even though local businesses might complain at the loss of through-trade; the predicted increase in traffic would become more than an unmitigated nuisance in the future. However, it rejected a slavish use of ring-roads around large towns. As the detailed plans of these schemes often demanded far more land for junctions and wide roads than would be acceptable, it would be better to place restrictions on the volume of traffic that could access the area in these cases.

Where restrictions were needed, this could often be achieved through some combination of licences or permits, parking restrictions, or subsidised public transport. However it recommended that the road user should not be denied too much access, and that restricting through congestion charging would not normally be the right approach, unless and until every possible alternative had been tested:

We think the public can justifiably demand to be fully informed about the possibilities of adapting towns to motor traffic before there is any question of applying restrictive measures.[5]

Innovatively, the report recommended that some areas should change their outlook; rather than facing onto the street, shops could face onto squares or pedestrianised streets, with roof top or multi-storey parking nearby. Urban areas need not consist of buildings set alongside vehicular streets, instead multiple levels could be used with traffic moving underneath a building deck, with snug pedestrian alleys and contrasting open squares containing fountains and artwork.

Schemes would need to be carefully considered when they incorporated historic buildings, but such schemes could not be applied to small areas. However, obsolete street patterns were already becoming frozen for decades by piecemeal rebuilding. Whilst these grand schemes would be expensive, the income from vehicle taxes could represent a regular source of income to draw from.

This approach differed from the shopping mall concept, which was designed for the car on greenfield or out of town sites, and did not address the development of the existing urban landscape.

Examples

The report looked at a range of scenarios based on real towns, and suggested treatments that would balance the desire to enrich people's lives through car ownership while still maintain pleasant urban centres.

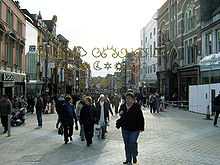

London (Oxford Street area)

Oxford Street, in London's West End "epitomizes the conflict between traffic and environment". The mixing of traffic and pedestrians had created "the most uncivilised street in Europe".[11]

The report had considered running car parks, through-traffic and access roads in shallow cuttings underground while raising the shop levels over four pedestrianised storeys 20 feet (6 metres) above it. However they concluded that this had already become impractical — for a generation at least — because of piecemeal redevelopment. Should this practice continue, the only choice would be ultimately to curtail vehicular access to the street.

Leeds – A large city

Leeds, as a large city, was too large to accommodate all the potential traffic, and it should instead attempt to curtail access, particularly private vehicles being used for commuting. Leeds embraced the approach and adopted the motto Motorway city of the 70s after it built an Outer Ring Road, a sunken part-motorway Inner Ring Road and a clockwise-only 'loop road' enclosing a part-pedestrianised city centre with several business and shopping centres. The protection and redevelopment of the city centre came at the cost of the large landtake required for the network of corridor roads and interchanges, predominantly at ground level, which required extensive demolition and severed the previous urban and suburban communities.

Newbury – a small town

Newbury was chosen as an example of a small town that could be redeveloped following this pattern, with vehicles easily integrating into the urban scenery. But the report warned that the commitment and scale of work required would be hitherto unheard of. The concept was mainly ignored for 25 years until the A34 Newbury bypass was proposed, alongside extensive pedestrianisation and road changes within the urban areas. The new roads dramatically reduced the impact of motor vehicles on the town, especially heavy goods vehicles,[12] and accompanied the reinvigoration of Newbury which had managed to retain its historic core.[13] When completed in 1998 the actual bypass followed approximately the same route as the original proposal,[14] but encountered such protest from so many quarters that all other UK road schemes were soon stalled. As a result the government and Highways Agency changed its policies and assessment criteria to evenly balance predictions of schemes' environmental impact with their economic, community and safety benefits[12]

Norwich – an ancient town

Norwich, as an ancient town, could retain its historic areas but this would be at the cost of reduced vehicular access.

Response and legacy

The RAC recognised that some conclusions were unpalatable, and controversial, but overall they welcomed the approach. However, they thought that restrictions on vehicular traffic would be acceptable to the motorist if they could see the government determined to build capacity in urban areas. The Pedestrian Association cautioned that "the Judgment of Solomon" would be needed to decide how to implement the ideas in the report.[15]

The Parliamentary transport committee welcomed the report, as it offered an alternative to simply building more roads or providing more public transport. Thus it gained political currency, with the report forming the blueprint for UK urban planning for the next few decades.

In doing so, it gave acceptability and confidence to a number of proposals and innovations that soon became common in the UK landscape:[8]

- urban clearways, flyovers, and the widespread used of single yellow and double yellow lines to limit the intrusion of vehicles in town centres

- pedestrianised precincts

- pedestrian city centres flanked with multi-storey car parks

- one-way streets and traffic restrictions

- separation of pedestrians and traffic, with clearly defined kerbs and pedestrian barriers

Buchanan later proposed a development for Bath using the same approach to reduce traffic in the historical city centre by way of underground routes; this provoked such a storm of local protest that "Buchanan's Tunnel" was never built.[8]

The recognition that road congestion could not be addressed just through new road programmes influenced the way that traffic problems would be addressed in future; there would now be a switch towards "transport studies" which should consider multi-modal solutions, i.e. both road and public transport options, including park and ride. However, in the absence of a central commitment to public transport the perspective was skewed in favour of road building for many years to come. By 1970 the government had committed to spend £4 bn on road schemes to "eliminate congestion" over the next 15 years.[10]

However, this switch to a multi-modal approach took some time to become widely accepted, and meanwhile many grand road schemes were being planned. By 1970 there were plans to spend £1,700 million on multiple Ringways and elevated radial roads across London. Robert Vigars, the chairman of the Greater London Council's Planning committee, reported that the plan for a part-buried Ringway 2 to supersede the South Circular Road between the A2 and A23 would necessitate the destruction of several thousand houses, but it was:[16]

...not just a traffic solution but a plan for the very people whose areas it passes through. It means creating living standards for them, so that they can live, breathe, shop and eat free from the menace of traffic congestion in their local streets. This was putting Buchanan into action ... We are satisfied that the total planning and environmental gains greatly outweigh the local difficulties.

Criticisms

As towns were developed according to the Buchanan blueprint, several issues emerged.

- Some of the grand plans that were called for have had a poor reputation in their implementation; to be able to predict future trends, mix social development, transport skills, and economic regeneration while performing slum clearance has often been beyond the capability of the local planners. Public accountability required by local government officers was sometimes stretched, with accusations of corruption with the private sector developers and contractors who put the plans into action. The cost inflation of schemes conspired with fluctuation of the property market and its subsequent collapse in the early 1970s left many plans incomplete. When conditions had improved conservation had once again become fashionable and confidence in the need for these centrally controlled grand plans had evaporated.[17]

- The courage needed to develop these schemes required a lot of political will, and this would sometimes falter. By failing to identify cheaper alternatives when the financial case weakened, "do-nothing" often became the default action. For example, the extensive plans to develop a series of orbital and distribution roads into central London resulted in the construction of the A40(M) Westway, the M41 cross route and A102(M) Blackwall tunnel. However, the wide impact of these schemes raised such controversy during the 1970s that many associated road schemes soon ran into concerted opposition. After the 1973 oil crisis, those remaining schemes fell into limbo, casting a planning blight over the affected areas for a decade or more until they were finally laid to rest. The recognition of environmental issues was also less well understood in the 1960s; the report's considerations were more for the human environment, rather than the natural issues which have tended to confound some subsequent road proposals.

- More latterly, this policy has been accused as being one of "predict and provide", or of building new roads in a congested network that fuel demand for more traffic, rather than meeting previous demands. This is to partly misrepresent the policy recommendations; although neither traffic generation and the deterrent effect of congestion, nor the mechanisms by which a business would choose to (re-)locate his premises was understood at the time, the report strove to strike a balance for situations when capacity demands could not or should not be met. Radical urban surgery was almost the opposite of what Buchanan was proposing, he later claimed:[1]

...in spite of all the effort, it was widely misinterpreted … the Report was a description of the choices open, from 'do nothing to whole hog', with the advantages and disadvantages set out.

- The separation of road users would often be taken to extremes in schemes: by moving motor vehicles onto dedicated routes, their interaction with pedestrians or cycle routes might occur less often but at higher speeds than before, and thus be far more hazardous or intimidating. New towns like Milton Keynes could avoid this by placing motorists, cyclists, and pedestrians on separate levels and routes. However, their interaction would be a particular problem in the established towns, especially in the transition to suburban areas where separation would be more ambiguous and inconsistent. In the search for low casualty rates, urban planners now look to detailed road designs and traffic calming to counteract this affect by reducing vehicle speeds, or take more dramatic steps by destroying this separation and mixing all road users together through shared space planning.

- At the heart of many of the new schemes was architecture of poor quality or poor design, and a poor understanding of the effects of the new road network. As warned by Buchanan, the detailed implementation of many of these schemes critically affected their success or failure. Subsequent research has shown that more is needed than a pedestrian centre with glass shop fronts and a hope that people will come and social life flourish.[18] One of the recommendations, that of integrating low level roads with developments on top, has been largely ignored; the costs and commitments needed for multi-level developments have been prohibitive in old town centres, especially when cheaper alternatives or out of town sites have presented themselves. New developments were often made in a fashionable modernist or brutalist style which rapidly dated, while the planners had not fully considered the social or economic factors that could lead to urban decay. The corridor or distribution roads would often have minimal overpasses or grade separation, with communities severed or blighted by noise and fumes. Drivers would refuse to be neatly compartmentalised into "travelling" along the corridor roads and "living" on the local roads, leading to businesses closing outside the prime sites.[19]

- Actual traffic growth has not been as extreme as envisaged in the report (although Buchanan did warn that he had selecting the more pessimistic projections). In 1963 36% of households had a car, by 1998 this had grown to 72%, considerably less than predicted.[20] This pattern of inaccuracy was a frequent issue with early transport schemes, which frequently overestimated vehicle ownership by about 20%, leading to a suspicion that they were often motivated by a feeling that they were important for "modernisation" for their own sake.[10]

Influences

The design of modern town schemes has been informed by the earlier policy decisions – and mistakes – in Britain, Europe and further afield. Auckland, for example, commissioned a plan from Buchanan for its road policies.[19]

By the mid 1970s it was evident that the previous focus on road traffic element was not enough; transport schemes were forced to widen the study area to include land use changes, and the effects of public transport, which continued to decline in popularity. This came to a head in 1976 when Nottingham rejected plans for new urban highways in favour of another (later also rejected) scheme to place access restrictions on cars entering the city centre. Instead, authorities' efforts were put to work improving the forecasting models, adjust local traffic management to squeeze more out of the current road system, directing heavy lorries away from minor roads, or subsidising public transport, which was now carrying fewer passengers and becoming uneconomic. The roads programme was scaled back to half its previous size mainly because of poor public finances, and urban regeneration became much more locally driven through "Strategic Plans".[10] Although many public policies and transport planners have promoted the creation of capacity-oriented solutions, organisations such as The Urban Motorways Committee (1972) adopted the need to respect the urban fabric. This movement has developed into a recognition of the need to effectively manage the demand for transport.[21]

Subsequent government planning policy on sustainable development adopted as consequence of the 1992 Earth Summit means that the concepts of vehicle restriction first mooted by Buchanan are slowly moving to the forefront of UK government policy. This has placed emphasis on alternatives to the private motor car, but has also embraced other techniques of restriction. Smeed's report of 1964 had proposed congestion charging as technically feasible, although Buchanan's recommendation had largely dismissed it. It took four decades for it to become politically acceptable in the UK, although this was not without controversy.[22]

Buchanan's concept of segregated zones or precincts, as pedestrian or local vehiclar areas, was derived from Assistant Commissioner H. Alker Tripp of Scotland Yard's Traffic Division. Buchanan's articulation of this concept encouraged the planners of the Dutch towns of Emmen and Delft, who were developing the concept of the woonerf, or living street, and decades later this was fed back to Britain, as the "home zone".[23]

Cities in the USA slowly came round to respond to the problems that Buchanan identified in 1963. A notable example is the elevated freeway system built in the late 1950s to provide extra capacity for Boston's traffic, which, at enormous financial cost, was demolished and rebuilt underground many decades later thus creating road capacity, urban pedestrian space, and reuniting displaced communities.[24]

See also

- Road protest (UK)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. 2007.

- ↑ "Professor Sir Colin Buchanan". Sinclair Knight Merz. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- ↑ Buchanan & 1964 location, p. Introduction.

- ↑ "Conservative Manifesto: The Next Five Years". 1959. p. not cited.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Buchanan & 1964 location, p. not cited.

- ↑ Buchanan & 1964 location, p. para. 68.

- ↑ Buchanan & 1964 location, p. para 30.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Professor Sir Colin Buchanan; Obituary". The Times. 2001-12-10.

- ↑ Buchanan & 1964 location, p. para 22.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Banister, David (2002). Transport Planning. p. not cited. ISBN 0-415-26172-4.

- ↑ "Obituary of Professor Sir Colin Buchanan". The Daily Telegraph. 2001-12-10.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Response to CPRE report on road bypasses". Highways Agency. 2006-070-03.

- ↑ Historic Newbury Fit for the Future (PDF). West Berkshire Council. 2006.

- ↑ Buchanan & 1964 location, p. paras. 153, 154, Figure 85.

- ↑ "Traffic Report's Proposals for Meeting Motor Age Threat to "Wreck Our Towns"". The Times. 1963-11-28. p. 16.

- ↑ "2,189 houses will go for London Ringway". The Times. 1969-07-18.

- ↑ Giddings; Hopwood. "A critique of Masterplanning as a technique for introducing urban design quality into British Cities" (PDF).

- ↑ van Ness, Akkelies. "Road Building and Urban Change" (PDF).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Boulter, Roger. "Where do walking and cycling fit in? Sustainable cities through urban planning" (PDF).

- ↑ "Households with regular use of a car, 1961-1998: Social Trends 30". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ Bayliss; Cuthbert; Stonham. "A Professional Framework for Transport Planning" (PDF). The Transport Planning Working Party. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ↑ "Brit media hit for unbalanced coverage of London toll". Toll Road News. 2004-05-11.

- ↑ Ward, Steven (2001-12-13). "Letters". The Guardian. p. 24.

- ↑ "History of The Central Artery / Tunnel Project". Massachusetts Turnpike Authority. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

Sources and further reading

- The Buchanan Report. London: HMSO. 1963.

- Traffic in Towns The specially shortened edition of the Buchanan Report S228. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. 1964.