Tornado climatology

The United States has the most tornadoes of any country, as well as the strongest and most violent tornadoes. This is mostly due to the unique geography of the continent and the size of the country. North America is a large continent that extends from the tropics south into arctic areas, and has no major east-west mountain range to block air flow between these two areas. In the middle latitudes, where most tornadoes of the world occur, the Rocky Mountains block moisture and buckle the atmospheric flow, forcing drier air at mid-levels of the troposphere due to downsloped winds, and causing cyclogenesis downstream to the east of the mountains. Downsloped winds off the Rockies force the formation of a dry line when the flow aloft is strong, while the Gulf of Mexico fuels abundant low-level moisture. This unique topography allows for frequent collisions of warm and cold air, the conditions that breed strong, long-lived storms throughout the year. A large portion of these tornadoes form in an area of the central United States known as Tornado Alley.[1] This area extends into Canada, particularly Ontario and the Prairie Provinces. Strong tornadoes also occur in northern Mexico.

The United States averaged 1,274 tornadoes per year in the last decade, along with Canada reporting nearly 100 annually in the southern regions.[2] However, the UK probably has most tornadoes per area per year, 0.14 per 1000 km².[3] Also the Netherlands have relatively many tornadoes per area. Also in absolute number of events, ignoring area, the UK experiences more tornadoes (excluding waterspouts) than any other European country.

Tornadoes kill an average of 52 people per year in Bangladesh, the most in the world. [citation needed] This is due to their high population density, poor quality of construction, lack of tornado safety knowledge, as well as other factors.[4][5] Other areas of the world that have frequent tornadoes include South Africa, parts of Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil, as well as portions of Europe, Australia and New Zealand, and far eastern Asia.[6][7]

The severity of tornadoes is commonly measured by the Enhanced Fujita Scale, which scales tornado intensity from EF0 to EF5 by wind speed and the amount of damage they do to human environments. These judgements are always made after the tornado has dissipated and its damage trail is carefully studied by weather professionals. [citation needed]

Tornadoes are most common in spring and least common in winter.[8] Since autumn and spring are transitional periods (warm to cool and vice versa) there are more chances of cooler air meeting with warmer air, resulting in thunderstorms. Tornadoes are focused in the right poleward section of landfalling tropical cyclones, which tend to occur in the late summer and autumn. Tornadoes can also be spawned as a result of eyewall mesovortices, which persist until landfall.[9] Favorable conditions can occur any time of the year.

Tornado occurrence is highly dependent on the time of day, because of solar heating.[10] Worldwide, most tornadoes occur in the late afternoon, between 3 pm and 7 pm local time, with a peak near 5 pm.[11][12][13][14][15] Destructive tornadoes can occur at any time of day. The Gainesville Tornado of 1936, one of the deadliest tornadoes in history, occurred at 8:30 am local time.[8]

Geography

.The United States has the most tornadoes of any country. Many of these form in an area of the central United States known as Tornado Alley.[1] This area extends into Canada, particularly Ontario and the Prairie Provinces; however, activity in Canada is less than that of the US.

Bangladesh and surrounding areas of eastern India suffer from tornadoes of lesser severity to those in the US with more regularity than any other region in the world. However, these occur with greater recurrence interval, and tend to be under-reported due to the scarcity of media coverage in a third-world country. The annual human death toll from tornadoes in Bangladesh is about 179 deaths per year, which is much greater than in the US. This is likely due to the density of population, poor quality of construction, lack of tornado safety knowledge, and other factors.[4]

Other areas of the world that have frequent strong tornadoes include parts of Argentina and southern Brazil, as well as South Africa. A fair number of weak and occasionally strong tornadoes occur annually in Germany, Italy, Spain, China and the Philippines. Australia, France, Russia, areas of the Middle East, India, Bangladesh and Japan have a history of multiple damaging tornado events.

Tornadoes in the USA

The United States averaged 1,274 tornadoes per year in the last decade. April 2011 saw the most tornadoes ever recorded for any month in the US National Weather Service's history, 875; the previous record was 542 in one month.[2] It has more tornadoes yearly than any other country and reports more violent (F4 and F5) tornadoes than anywhere else.

Tornadoes are common in many states but are most common to the west of the Appalachian Mountains and to the east of the Rockies. The Atlantic seaboard states - North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Virginia - are also very vulnerable, as well as Florida. The areas most vulnerable to tornadoes are the Southern Plains and Florida, though most Florida tornadoes are relatively weak. The Southern USA is one of the worst affected regions in terms of casualties.

Tornado reports have been officially collated since 1950. These reports have been gathered by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), based in Asheville, North Carolina. A tornado can be reported more than once, such as when a storm crosses a county line and reports are made from two counties.

Common misconceptions

Some people mistakenly believe that tornadoes only occur in the countryside. This is hardly the case. While it is true that the plains states are the most tornado-prone places in the nation, it should be noted that tornadoes have been reported in every U.S state, including Alaska and Hawaii. One likely reason why tornadoes are so common in the central U.S is because this is where Arctic air first collides with warm tropical air from the Gulf of Mexico where the cold front has not been "weakened" yet. As it heads further east, however, it is possible for the front to lose its strength as it travels over more warm air. Therefore, tornadoes are not as common on the East Coast as they are in the Midwest. However, they have happened on rare occasion, such as the F2 twister that struck the northern suburbs of New York City on July 12, 2006,[16] the EF2 twister in parts of Brooklyn, New York on August 8, 2007 or the F4 tornado that struck La Plata, Maryland on the 28th of April 2002.

Tornadoes can occur west of the continental divide, but they are infrequent and usually relatively weak and short-lived. Recently tornadoes have struck the Pacific coast town of Lincoln City, Oregon (1996); Sunnyvale, California (1998); and downtown Salt Lake City, Utah (1999) (see Salt Lake City Tornado). The California Central Valley is an area of some frequency for tornadoes, albeit of weak intensity. Though tornadoes that occur on the Western Seaboard typically are weak, more powerful, damaging tornadoes can occur, such as a tornado that occurred on May 22, 2008 in Perris, California.[17] More tornadoes occur in Texas than in any other US state.

The state which has the highest number of tornadoes per unit area is Florida, although most of the tornadoes in Florida are weak tornadoes of F0 or F1 intensity. A number of Florida's tornadoes occur along the edge of hurricanes that strike the state. The state with the highest number of strong tornadoes per unit area is Oklahoma. The neighboring state of Kansas is another particularly notorious tornado state. It records the most F4 and F5 tornadoes in the country.

Tornadoes in Canada

Canada also experiences numerous tornadoes, although fewer than the United States. In Canada, at least 80-100 tornadoes occur annually (with many more likely undetected in large expanses of unpopulated areas), causing tens of millions of dollars in damage.[citation needed] Most are weak F0 or F1 in intensity, but there are on average a few F2 or stronger that touch down each season.

For example, the tornado frequency of Southwestern Ontario is about half that of the most prone areas of the central US plains. The last multiple tornado-related deaths in Canada were caused by a tornado in Ear Falls, Ontario, on July 9, 2009, where 3 died, and the last killer tornado was on August 21, 2011 in Goderich, Ontario. The two deadliest tornadoes on Canadian soil were the Regina Cyclone of June 30, 1912 (28 fatalities) and the Edmonton Tornado of July 31, 1987 (27 fatalities). Both of these storms were rated an F4 on the Fujita scale. The city of Windsor was struck by strong tornadoes four times within a 61-year span (1946, 1953, 1974, 1997) ranging in strength from an F2 to F4. Windsor has been struck by more significant tornadoes than any other city in Canada.[citation needed] Canada's first official F5 tornado struck Elie, Manitoba on June 22, 2007.[18] At least two other tornadoes in Saskatchewan in earlier parts of the 20th century are suspected as F5.[citation needed] Tornadoes are most frequent in the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario.

Europe

Europe has about 700 tornadoes per year[19] – much more than estimated by Alfred Wegener in his classic book "Wind- und Wasserhosen in Europa" (Tornadoes and Waterspouts in Europe). They are most common in June–August, especially in the inlands – rarest in January–March. Strong and violent tornadoes (F3–F5) do occur, especially in some of the interier areas and in the south – but are not as common as in parts of the USA. As in the USA, tornadoes are far from evenly distributed. Europe has some small “tornado alleys” – probably because of frontal collitions as in the south and east of England,[20] but also because Europe is partitioned by mountain ranges like the Alps. Parts of Styria (Steiermark) in Austria may be such a tornado alley, and this county has had at least three F3 tornadoes since 1900.[21] F3 and perhaps one F4 tornado have occurred as far north as Finland.

Since 1900, deadly tornadoes have occurred in Belgium, France, Cyprus, Russia, Poland, Portugal (such as the F3/T7 of Castelo Branco on November 6, 1954, which killed 5 and injured 220), Wales, England, Scotland, Austria, Italy (such as the F5/T10 of Udine-Treviso on July 24, 1930, which killed 23 people,[22]) Malta, and Finland. The 1984 Ivanovo–Yaroslavl outbreak, with more than 400 fatalities and 213 injured, was the century’s deadliest tornado or outbreak in Europe. It included at least one F5 and one F4. Europe’s perhaps deadliest tornado ever (and probably one of the World’s deadliest tornadoes) hit Malta in 1551 (or 1556) and killed about 600.

One notable tornado of recent years was the tornado which struck Birmingham, United Kingdom, in July 2005. A row of houses was destroyed, but no one was killed. A strong F3 (T7) Tornado hit the small town Micheln in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany on July 23, 2004 leaving 6 people injured and more than 250 buildings massively damaged.[23]

Asia

Bangladesh and the eastern parts of India are exposed to tornadoes. They do also occur in e.g. Pakistan and Israel. On April 4, 2006, a rare F2 tornado hit northwestern Israel, causing significant damage and injuries.

South America

Argentina has pockets with high tornadic activity. Strong tornadoes are reported from Uruguay, Paraguay and Brazil.

Africa

Tornadoes do occur in South Africa. In October 2011 (i.e. in the spring), two people were killed and nearly 200 were injured after a tornado formed. Near Ficksburg in the Free State, more than 1,000 shacks and houses were flattened.[24]

Oceania

Australia has about 16 tornadoes per year - excluding waterspouts, which are common.[25] In New Zealand, a tornado hit the northern suburbs of Auckland on May 3, 2011, killing one and injuring at least 16 people.[26]

Frequency of occurrence

Tornadoes can form in any month, providing the conditions are favorable. For example, a freak tornado hit South St. Louis County Missouri on December 31, 2010, causing pockets of heavy damage to a modest area before dissipating. The temperature was unseasonably warm that day. They are least common during the winter and most common in spring. Since autumn and spring are transitional periods (warm to cool and vice versa) there are more chances of cooler air meeting with warmer air, resulting in thunderstorms. Tornadoes in the late summer and fall can also be caused by hurricane landfall.

Not every thunderstorm, supercell, squall line, or tropical cyclone will produce a tornado. Precisely the right atmospheric conditions are required for the formation of even a weak tornado. On the other hand, 700 or more tornadoes a year are reported in the contiguous United States.

On average, the United States experiences 100,000 thunderstorms each year, resulting in more than 1,200 tornadoes and approximately 50 deaths per year. The deadliest U.S. tornado recorded is the March 18, 1925, Tri-State Tornado that swept across southeastern Missouri, southern Illinois and southern Indiana, killing 695 people. The biggest tornado outbreak on record—with 353 tornadoes over the course of just 3 1/2 days, including four F5 and eleven F4 tornadoes—occurred starting on April 25, 2011 and intensifying on April 26 and especially the record-breaking day of April 27 before ending on April 28. It is named properly, April 25–28, 2011 tornado outbreak but often called the second Super Outbreak. Previously, the record was 148 tornadoes, dubbed the (original) Super Outbreak. Another such significant storm system was the Palm Sunday tornado outbreak of 1965, which affected the United States Midwest on April 11, 1965. A series of continuous tornado outbreaks is known as a tornado outbreak sequence, with significant occurrences in May 1917, 1930, 1949, and 2003.

Time of occurrence

Diurnality

Tornado occurrence is highly dependent on the time of day. [10] Austria, Finland, Germany, and the United States'[27] peak hour of occurrence is 5 p.m., with roughly half of all tornado occurrence between 3 p.m. and 7 p.m. local time,[28][29] due to this being the time of peak atmospheric heating, and thus the maximum available energy for storms; some researchers, including Howard B. Bluestein of the University of Oklahoma, have referred to this phenomenon as "five o'clock magic." Despite this, there are several morning tornadoes reported, like the Seymour, Texas one in April 1980.

Seasonality

The time of year is a big factor of the intensity and frequency of tornadoes. On average, in the United States as a whole, the month with the most tornadoes is May, followed by the months June, April, and July. There is no "tornado season" though, as tornadoes, including violent tornadoes and major outbreaks, can and do occur anywhere at any time of year if favorable conditions develop. Major tornado outbreaks have occurred in every month of the year.

July is the peak month in Austria, Finland, and Germany.[30] On average, there are around 294 tornadoes throughout the United States during the month of May, and as many as 543 tornadoes have been reported in the month of May alone (in 2003). The months with the fewest tornadoes are usually December and January, although major tornado outbreaks can and sometimes do occur even in those months. In general, in the Midwestern and Plains states, springtime (especially the month of May) is the most active season for tornadoes, while in the far northern states (like Minnesota and Wisconsin), the peak tornado season is usually in the summer months (June and July). In the colder late autumn and winter months (from early December to late February), tornado activity is generally limited to the southern states, where it is possible for warm Gulf of Mexico air to penetrate.

The reason for the peak period for tornado formation being in the spring has much to do with temperature patterns in the U.S. Tornadoes often form when cool, polar air traveling southeastward from the Rockies overrides warm, moist, unstable Gulf of Mexico air in the eastern states. Tornadoes therefore tend to be commonly found in front of a cold front, along with heavy rains, hail, and damaging winds. Since both warm and cold weather are common during the springtime, the conflict between these two air masses tends to be most common in the spring. As the weather warms across the country, the occurrence of tornadoes spreads northward. Tornadoes are also common in the summer and early fall because they can also be triggered by hurricanes, although the tornadoes caused by hurricanes are often much weaker and harder to spot. Winter is the least common time for tornadoes to occur, since hurricane activity is virtually non-existent at this time, and it is more difficult for warm, moist maritime tropical air to take over the frigid Arctic air from Canada, occurrences are found mostly in the Gulf states and Florida during winter (although there have been some notable exceptions). Interestingly, there is a second active tornado season of the year, late October to mid-November. Autumn, like spring, is a time of the year when warm weather alternates with cold weather frequently, especially in the Midwest, but the season is not as active as it is during the springtime and tornado frequencies are higher along the Atlantic Coastal plain as opposed to the Midwest. They usually appear in late summer.

Long-term trends

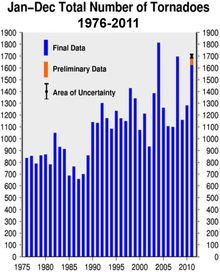

The reliable climatology of tornadoes is limited in geographic and temporal scope; only since 1976 in the United States and 2000 in Europe have thorough and accurate tornado statistics been logged.[31][32] However, some trends can be noted in tornadoes causing significant damage in the United States, as somewhat reliable statistics on damaging tornadoes exist as far back as 1880. The highest incidence of violent tornadoes seems to shift from the Southeastern United States to the southern Great Plains every few decades. Also, the 1980s seemed to be a period of unusually low tornado activity in the United States, and the number of multi-death tornadoes decreased every decade from the 1920s to the 1980s, suggesting a multi-decadal pattern of some sort.[33]

See also

- Tornado intensity and damage

- Tornado records

- List of tornadoes and tornado outbreaks

- List of F5 and EF5 tornadoes

- Tornadogenesis

- Tornado myths

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Perkins, Sid (2002-05-11). "Tornado Alley, USA". Science News. pp. 296–298. Archived from the original on 2006-08-25. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/2011_tornado_information.html

- ↑ http://www.dandantheweatherman.com/Bereklauw/dutchtns.htm

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Paul, Bhuiyan (2004). "The April 2004 Tornado in North-Central Bangladesh: A Case for Introducing Tornado Forecasting and Warning Systems" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-08-17.

- ↑ Finch, Jonathan D. "Bangladesh and East India Tornadoes Background Information". Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Tornado: Global occurrence". Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ↑ Graf, Michael (June 2008). "Synoptical and mesoscale weather situations associated with tornadoes in Europe" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Grazulis, Thomas P (July 1993). Significant Tornadoes 1680–1991. St. Johnsbury, VT: The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- ↑ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division (2006-10-04). "Frequently Asked Questions: Are TC tornadoes weaker than midlatitude tornadoes?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kelly, Schaefer, McNulty, et al. (1978-04-10). "An Augmented Tornado Climatology" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. p. 12. Retrieved 2006-09-13.

- ↑ "Tornado: Diurnal patterns". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007. p. 6. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ Holzer, A. M. (2000). "Tornado Climatology of Austria". Atmospheric Research (56): 203–211. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ Dotzek, Nikolai (2000-05-16). "Tornadoes in Germany" (PDF). Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ "South African Tornadoes". South African Weather Service. 2003. Archived from the original on 2007-05-26. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

- ↑ Finch, Jonathan D.; Dewan, Ashraf M. "Bangladesh Tornado Climatology". Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ OConnor, Anahad (2006-07-14). "Its Official: That Severe Storm in Westchester Was a Tornado". The New York Times.

- ↑ Reyes, David (2008-05-23). "Tornadoes, hail and snow deliver a May surprise". The Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Environment Canada News Release: Elie Tornado Upgraded to Highest Level on Damage Scale

- ↑ http://geography.about.com/b/2003/07/13/tornadoes-in-europe.htm

- ↑ Paul Rincon: UK, Holland top twister league. By Paul Rincon, BBC Science

- ↑ http://www.tordach.org/at/Tornado_climatology_of_Austria.html

- ↑ http://www.tornadoit.org/tornadostorici.htm

- ↑ Sävert, Thomas. "2004 tornado in Micheln (in German)". Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- ↑ http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/world_now/2011/10/south-africa-tornadoes-tear-through-townships-killing-two-and-leaving-hundreds-homeless.html

- ↑ http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2010/06/04/2918660.htm

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-13263881

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica. Tornadoes. Retrieved on 2006-10-25.

- ↑ A. M. Holzer. Tornado Climatology of Austria. Retrieved on 2006-10-25.

- ↑ N. Dotzek. Tornadoes in Germany. Retrieved on 2006-10-25.

- ↑ Jenni Teittinen. A Climatology of Tornadoes in Finland. Retrieved on 2006-10-25.

- ↑ Grazulis, pg. 194

- ↑ "ESSL [ESWD Project and Data Use]". European Severe Storms Laboratory. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ Grazulis, 196-198

Book references

- Grazulis, Thomas P (July). Significant Tornadoes 1680–1991. St. Johnsbury, VT: The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

Further reading

- Brooks, Harold E. (2004). "Estimating the Distribution of Severe Thunderstorms and Their Environments Around the World". International Conference on Storms. Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

- Brooks, Harold; C.A. Doswell III (Jan 2001). "Some aspects of the international climatology of tornadoes by damage classification". Atmos. Res. 56 (1-4): 191–201. doi:10.1016/S0169-8095(00)00098-3.

- Brooks, Harold E.; J.W. Lee and J.P. Craven (Jul 2003). "The spatial distribution of severe thunderstorm and tornado environments from global reanalysis data". Atmos. Res. 67-68: 73–94. doi:10.1016/S0169-8095(03)00045-0.

- Dotzek, Nikolai; J. Grieser, H.E. Brooks (Jul-Sep 2003). "Statistical modeling of tornado intensity distributions". Atmos. Res. 67-68: 163–87. doi:10.1016/S0169-8095(03)00050-4.

- Feuerstein, Bernold; N. Dotzek, Jürgen Grieser (Feb 2005). "Assessing a Tornado Climatology from Global Tornado Intensity Distributions". J. Climate 18 (4): 585–96. Bibcode:2005JCli...18..585F. doi:10.1175/JCLI-3285.1.

External links

- U.S. Severe Thunderstorm Climatology (NSSL)

- U.S. Tornado Climatology (NCDC)

- U.S. Tornado Climatology (University of Nebraska–Lincoln)

- When and Where Do Tornadoes Occur? (National Atlas of the United States)