Topkapı Palace

| Topkapı Palace | |

|---|---|

|

Topkapı Sarayı طوپقپو سرايى | |

Topkapı Palace from the Bosphorus | |

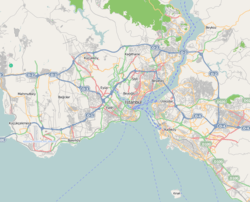

Location in Istanbul

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Palace (1453-1853), Accommodation for ranked officers (1853-1924), Museum (1924-present) |

| Architectural style | Ottoman, Baroque |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Coordinates | 41°0′46.8″N 28°59′2.4″E / 41.013000°N 28.984000°E |

| Construction started | mid-15th century |

| Client | Ottoman sultans |

| Owner | Turkish state |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | various low buildings surrounding courtyards, pavilions and gardens |

| Size | 592,600 to 700,000 m2 (6,379,000 to 7,535,000 sq ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Mehmed II, Alaüddin, Davud Ağa, Mimar Sinan, Sarkis Balyan |

The Topkapı Palace (Turkish: Topkapı Sarayı[1] or in Ottoman Turkish: طوپقپو سرايى) is a large palace in Istanbul, Turkey, that was the primary residence of the Ottoman Sultans for approximately 400 years (1465-1856) of their 624-year reign.[2]

As well as a royal residence, the palace was a setting for state occasions and royal entertainments. It is now a major tourist attraction and contains important holy relics of the Muslim world, including Muhammed's SAW cloak and sword.[2] The Topkapı Palace is among the monuments contained within the "Historic Areas of Istanbul", which became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985, and is described under UNESCO's criterion iv as "the best example[s] of ensembles of palaces [...] of the Ottoman period."[3]

The palace complex consists of four main courtyards and many smaller buildings. At its peak, the palace was home to as many as 4,000 people,[2] and covered a large area with a long shoreline. It contained mosques, a hospital, bakeries, and a mint.[2] Construction began in 1459, ordered by Sultan Mehmed II, the conqueror of Byzantine Constantinople. It was originally called the New Palace (Yeni Sarayı) to distinguish it from the previous residence. It received the name "Topkapı" (Cannon Gate[4]) in the 19th century, after a (now lost) gate and shore pavilion. The complex was expanded over the centuries, with major renovations after the 1509 earthquake and the 1665 fire.

After the 17th century the Topkapı Palace gradually lost its importance as the sultans preferred to spend more time in their new palaces along the Bosphorus. In 1856, Sultan Abdül Mecid I decided to move the court to the newly built Dolmabahçe Palace, the first European-style palace in the city. Some functions, such as the imperial treasury, the library, and the mint, were retained in the Topkapı Palace.

Following the end of the Ottoman Empire in 1923, Topkapı Palace was transformed by a government decree dated April 3, 1924 into a museum of the imperial era. The Topkapı Palace Museum is administered by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. The palace complex has hundreds of rooms and chambers, but only the most important are accessible to the public today. The complex is guarded by officials of the ministry as well as armed guards of the Turkish military. The palace includes many fine examples of Ottoman architecture. It contains large collections of porcelain, robes, weapons, shields, armor, Ottoman miniatures, Islamic calligraphic manuscripts and murals, as well as a display of Ottoman treasures and jewelry.

History

Site

The palace complex is located on the Seraglio Point (Sarayburnu), a promontory overlooking the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara, with a good view of the Bosphorus from many points of the palace. The site is hilly and one of the highest points close to the sea. During Greek and Byzantine times, the acropolis of the ancient Greek city of Byzantion stood here. There is an underground Byzantine cistern located in the Second Courtyard, which was used throughout Ottoman times, as well as remains of a small church, the so-called Palace Basilica on the acropolis, which have been excavated in modern times. The nearby Church of Hagia Eirene, though located in the First Courtyard, is not considered a part of the old Byzantine acropolis.

Initial construction

After the Ottoman conquest in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II found the imperial Byzantine Great Palace of Constantinople largely in ruins.[5] The Ottoman court initially set itself up in the Old Palace (Eski Sarayı), today the site of Istanbul University. The Sultan then searched for a better location and chose the old Byzantine acropolis, ordering the construction of a new palace in 1459.

Layout

.JPG)

.JPG)

Sultan Mehmed II established the basic layout of the palace. He used the highest point of the promontory for his private quarters and innermost buildings.[6] Various buildings and pavilions surrounded the innermost core and grew down the promontory towards the shores of the Bosphorus. The whole complex was surrounded by high walls, some of which date back to the Byzantine acropolis. This basic layout governed the pattern of future renovations and extensions. According to an account of the contemporary historian Critobulus of Imbros the sultan also

"... took care to summon the very best workmen from everywhere - masons and stonecutters and carpenters ... For he was constructing great edifices which were to be worth seeing and should in every respect vie with the greatest and best of the past. For this reason he needed to give them the most careful oversight as to workmen and materials of many kinds and the best quality, and he also was concerned with the very many and great expenses and outlays."[7]

Accounts differ as to when construction of the inner core of the palace started and was finished. Kritovolous gives the dates 1459-1465; other sources suggest a finishing date in the late 1460s.[8]

Unlike some other royal residences that had strict master plans, such as Schönbrunn Palace or the Palace of Versailles, Topkapı Palace developed over the course of centuries, with sultans adding and changing various structures and elements. The resulting asymmetry is the result of this erratic growth and change over time,[9] although the main layout by Mehmed II was preserved. Most of the changes occurred during the reign of Sultan Suleyman from 1520 to 1560. With the rapid expansion of the Ottoman Empire, Suleyman wanted its growing power and glory to be reflected in his residence, and new buildings were constructed or enlarged. The chief architect in this period was the Persian Alaüddin, also known as Acem Ali.[10] He was also responsible for the expansion of the Harem.

In 1574, a great fire destroyed the kitchens. Sinan was entrusted by Sultan Selim II to rebuild the destroyed parts, which he did, expanding them, as well as the Harem, baths, the Privy Chamber and various shoreline pavilions.[10] By the end of the 16th century, the palace had acquired its present appearance.

The palace is an extensive complex rather than a single monolithic structure, with an assortment of low buildings constructed around courtyards, interconnected with galleries and passages. Few of the buildings exceed two stories. Interspersed are trees, gardens and water fountains, to give a refreshing feeling to the inhabitants and to provide places to rest. The buildings enclosed the courtyards, and life revolved around them. Doors and windows face the courtyard to create an open atmosphere and provide cool air during hot summers.

The palace compound, seen from above, is a rough rectangle, divided into four main courtyards and the harem. The main axis is from south to north, the outermost (first) courtyard starting at the south, with each successive courtyard leading north. The first courtyard was the most accessible one, while the innermost (fourth) courtyard and the harem were the most inaccessible, being the sole private domain of the sultan. The fifth courtyard was in reality the outermost rim of the palace grounds bordering the sea. Access to these courtyards was restricted by high walls and controlled with gates. Apart from the four to five main courtyards, various other small to mid-sized courtyards exist throughout the complex. The total size of the complex varies from around 592,600 square meters[11] to 700,000 square meters, depending on which parts are counted.[12]

The southern and western sides border the large former imperial flower park, today Gülhane Park. Surrounding the palace compound on the southern and eastern side is the Sea of Marmara. Various related buildings such as small summer palaces (kasrı), pavilions, kiosks (köşkü) and other structures for royal pleasures and functions formerly existed at the shore in an area known as the Fifth Place, but have disappeared over time due to neglect and the construction of the shoreline railroad in the 19th century. The last remaining seashore structure that still exists today is the Basketmakers' Kiosk, constructed in 1592 by Sultan Murad III. The total area of Topkapı Palace was in fact much larger than what it is today.

Function

Topkapı Palace was the main residence of the sultan and his court. It was initially the seat of government as well as the imperial residence. Even though access was strictly regulated, inhabitants of the palace rarely had to venture out since the palace functioned almost as an autonomous entity, a city within a city. Audience and consultation chambers and areas served for the political workings of the empire. For the residents and visitors, the palace had its own water supply through underground cisterns and the great kitchens provided for nourishment on a daily basis. Dormitories, gardens, libraries, schools, even mosques, were at the service of the court. Attached to the palace were diverse imperial societies of artists and craftsmen collectively called the Ehl-i Hiref (Community of the Talented), which produced some of the finest work in the whole empire.

A strict, ceremonial, codified daily life ensured imperial seclusion from the rest of world.[13] One of the central tenets was the observation of silence in the inner courtyards. The principle of imperial seclusion is a tradition that was probably continued from the Byzantine court. It was codified by Mehmed II in 1477 and 1481 in the Kanunname Code, which regulated the rank order of court officials, the administrative hierarchy, and protocol matters.[14] This principle of increased seclusion over time was reflected in the construction style and arrangements of various halls and buildings. The architects had to ensure that even within the palace, the sultan and his family could enjoy a maximum of privacy and discretion, making use of grilled windows and building secret passageways.[15]

Imperial Gate

The main street leading to the palace is the Byzantine processional Mese avenue, today Divan Yolu (Street of the Council). The Mese was used for imperial processions during the Byzantine and Ottoman era. It leads directly to the Hagia Sophia and takes a turn northwest towards the palace square where the landmark Fountain of Ahmed III stands. The sultan would enter the palace through the Imperial Gate (Turkish: Bâb-ı Hümâyûn or Latin: Porta Augusta), also known as "Gate of the Sultan" (Turkish: Saltanat Kapısı) located to the south of the palace.[16] This massive gate, originally dating from 1478, is now covered in 19th-century marble. The massiveness of this stone gate accentuates its defensive character. Its central arch leads to a high-domed passage. Gilded Ottoman calligraphy adorns the structure at the top, with verses from the Qur'an and tughras of the sultans. Identified tughras are of Sultan Mehmed II and Abdül Aziz I, who renovated the gate.[17]

One of the inscriptions at the gate proclaims:By the Grace of God, and by His approval, the foundations of this auspicious castle were laid, and its parts were solidly joined together to strengthen peace and tranquility. This blessed castle, with the aim of ensuring safety of Allah's support and the consent of the son of Sultan Mehmed, son of Sultan Murad, sultan of the land, and ruler of the seas, the shadow of Allah on the people and demons, God's deputy in the east and west, the hero of water and soil, the conqueror of Constantinople and the father of its conquest, Sultan Mehmed Khan- May Allah make eternal his empire, and exalt his residence above the most lucid stars of the firmament."

On each side of the hall are rooms for the guard. The gate was open from morning prayer until the last evening prayer.

According to old documents, there was a wooden apartment above the gate area until the second half of the 19th century.[18] It was used first as a pavilion by Mehmed, later as a depository for the properties of those who died inside the palace without heirs and eventually as the receiving department of the treasury. It was also used as a vantage point for the ladies of the harem on special occasions.[19]

The Imperial Gate is the main entrance into the First Courtyard. The four courtyards lead to each other and during the Ottoman Empire, each became steadily more exclusive leading to the Fourth Courtyard, which was the sultan's private courtyard.[2]

First Courtyard

The First Courtyard (I. Avlu or Alay Meydanı) spans Seraglio Point and is surrounded by high walls.[20]

This First Courtyard functioned as an outer precinct or park and is the largest of all the courtyards of the palace. The steep slopes leading towards the sea had already been terraced under Byzantine rule.

The First Courtyard contained purely functional structures and some royal ones, many of which don't exist today.[21] The structures that remain are the former Imperial Mint (Darphane-i Âmire, constructed in 1727), the church of Hagia Irene and various fountains. The Byzantine church of Hagia Irene was never destroyed by the conquering Ottomans and survived by being used as a storehouse and imperial armoury.[22]

This court was also known as the Court of the Janissaries or the Parade Court. Visitors entering the palace would follow the path towards the Gate of Salutation and the Second Courtyard of the palace. Court officials and janissaries would line the path dressed in their best garbs and waiting. Visitors had to dismount from the horses between the First and the Second Courtyard.[23]

Gate of Salutation

The large Gate of Salutation (Arabic: Bâb-üs Selâm), also known as the Middle Gate (Turkish: Orta Kapı), leads into the palace and the Second Courtyard. This crenelated gate has two large octagonal pointed towers. The date of construction of this gate is not clear, since the architecture of the towers is of Byzantine influence rather than Ottoman. It is speculated that the gate emulates the Gate of St. Barbara (Cannon Gate), which used to be the royal seaside entrance to the palace gardens from the shore of the Bosphorus.[24] An inscription at the door dates this gate to at least 1542. In a miniature painting from the Hünername from 1584, a low-roofed structure with three windows above the arch between the towers is clearly visible,[25] probably a guards' hall that has since disappeared.[26] The gate is richly decorated on both sides and in the upper part with religious inscriptions and monograms of sultans.

No one apart for official purpose and foreign dignitaries were allowed passage through the gate. All visitors had to dismount by the Middle Gate, since only the sultan was allowed to enter the gate on horseback.[27] This was also a Byzantine tradition taken from the Chalke Gate of the Great Palace.

The Fountain of the Executioner (Cellat Çeşmesi) is where the executioner purportedly washed his hands and sword after a decapitation, although there is disagreement if this is indeed that particular fountain. It is located on the right side when facing the Gate of Salutation from the First Courtyard.[28]

Second Courtyard

Upon passing the Middle Gate, the visitor enters the Second Courtyard (II. Avlu), or Divan Square (Divan Meydanı), which was a park full of peacocks and gazelles, used as a gathering place for courtiers.[29][30] This courtyard is considered the outer one (Birûn). Only the Sultan was allowed to ride on the black pebbled walks that lead to the Third Courtyard.

The courtyard was completed probably around 1465 during the reign of Mehmed II, but received its final appearance around 1525-1529 during the reign of Suleyman I.[30] This courtyard is surrounded by the former palace hospital, bakery, Janissary quarters, stables, the imperial harem and Divan to the north and the kitchens to the south. At the end of the courtyard, the Gate of Felicity marks the entrance to the Third Courtyard. The whole area is unified by a continuous marble colonnade, creating an ensemble.

Numerous artifacts from the Roman and Byzantine periods have been found on the palace site during recent excavations. These include sarcophagi, baptismal fonts, parapet slabs and pillars and capitals. They are on display in the Second Courtyard in front of the imperial kitchens. Located underneath the Second Courtyard is a cistern that dates to Byzantine times. It is normally closed to the public.

The Second Courtyard was primarily used by the sultan to dispense justice and hold audiences. This was done here also to impress visitors. Various Austrian, Venetian and French ambassadors have left accounts of what such an audience looked like. The French ambassador Philippe du Fresne-Canaye led an embassy in 1573 to the sultan:

At the right hand was seated the Agha of Janissaries, very near the gate, and next to him some of the highest grandees of the court. The Ambassador saluted them with his head and they got up from their seats and bowed to him. And at a given moment all the Janissaries and other soldiers who had been standing upright and without weapons along the wall of that court did the same, in such a way that seeing so many turbans incline together was like observing a fast field of ripe corn moving gently under the light puff of Zephyr […] We looked with great pleasure and even greater admiration at this frightful number of Janissaries and other soldiers standing all along the walls of this court, with hands joined in front in the manner of monks, in such silence that it seemed we were not looking at men but statues. And they remained immobile in that way more than seven hours, without talking or moving. Certainly it is most impossible to comprehend this discipline and this obedience when one has not seen it […][31]

A strict protocol that governed the functioning and workings of the Second Courtyard was to ensure discipline and respect, as well as lend an air of majesty to the court.

Imperial carriages

Directly behind the Gate of Salutation, on the northeast side, the imperial carriages are temporarily exhibited in the former outer stables and harness rooms. This is a relatively low building, altered in 1735 when a new ceiling was installed. Its roof is one of the few undomed roofs to retain its 15th-century shape. Many carriages were destroyed in a fire in the previous stables in the late 19th century. The carriages on display are some of the sultan's carriages, including the state carriage, the carriage of the Valide Sultan (Queen Mother), and minor court carriages. Some of the carriages were foreign-made vehicles that were imported for the court. Located next to the carriages to the north are the extensive palace kitchens.

Palace kitchens

The elongated palace kitchens (Saray Mutfakları) are a prominent feature of the palace. Some of the kitchens were first built in the 15th century at the time when the palace was constructed. They were modeled on the kitchens of the Sultan's palace at Edirne. They were enlarged during the reign of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent but burned down in 1574. The kitchens were remodeled and brought up to date according to the needs of the day by the court architect Mimar Sinan.[32]

Rebuilt to the old plan by Sinan, they form two rows of 20 wide chimneys (added by Sinan), rising like stacks from a ship from domes on octagonal drums. The kitchens are arranged on an internal street stretching between the Second Courtyard and the Sea of Marmara. The entrance to this section is through the three doors in the portico of the Second Courtyard: the Imperial commissariat (lower kitchen) door, imperial kitchen door and the confectionery kitchen door.

The palace kitchens consist of 10 domed buildings: Imperial kitchen, Enderûn (palace school), Harem (women’s quarters), Birûn (outer service section of the palace), kitchens, beverages kitchen, confectionery kitchen, creamery, storerooms and rooms for the cooks. They were the largest kitchens in the Ottoman Empire. The meals for the Sultan, the residents of the Harem, Enderûn and Birûn (the inner and outer services of the palace) were prepared here. Food was prepared for about 4,000 people. The kitchen staff consisted of more than 800 people, rising to 1,000 on religious holidays. As many as 6,000 meals a day could be prepared. Even the serving of food to the sultan was strictly regulated by protocol.[33]

The kitchens included dormitories, baths and a mosque for the employees, most of which disappeared over time.[34]

Apart from exhibiting kitchen utensils, today the buildings contain a silver gifts and utensils collection, as well as large collections of Chinese blue-and-white, white, and celadon porcelain.

Porcelain and celadon collection

Chinese and Far Eastern porcelain was highly valued and was transported by camel caravans over the Silk Road or by sea. The 10,700 pieces of Chinese porcelain displayed here[35] are rare, precious, and thought to rival that found in China as one of the finest collections in the world.[2] The Chinese porcelain collection ranges from the late Song Dynasty (960-1279) and the Yuan Dynasty (1280–1368), through the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) to the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). This museum also contains one of the world's largest collections of 14th-century Longquan celadon. The collection has around 3,000 pieces of Yuan and Ming Dynasty celadons.[36] Those celadon were valued by the Sultan and the Queen Mother because it was supposed to change colour if the food or drink it carried was poisoned.[37] The Japanese collection is mainly Imari porcelain, dating from the 17th to the 19th centuries. Further parts of the collection include white porcelain from the beginning of the 15th century and "imitation" Blue-and-White and Imari porcelain from Vietnam, Thailand and Persia.[38]

Imperial stables

Located on the other side of the courtyard, around five to six meters below ground level, are the imperial stables (Istabl-ı Âmire). The stables include the privy stables (Has Ahir) and were constructed under Mehmed II and renovated under Suleyman. A vast collection of harness treasures (Raht Hazinesi) is kept in the privy stables. Also located there is the small 18th-century mosque and bath of Beşir Ağa (Beşir Ağa Camii ve Hamamı), the chief black eunuch of Mahmud I.[39]

Dormitories of the Halberdiers with Tresses

At the end of the imperial stables are the Dormitories of the Halberdiers with Tresses (Zülüflü Baltacılar Koğušu). These quarters were used by a corps that was responsible for carrying wood to the palace rooms, cleaning and serving service for the harem and the quarters of the male pages, moving furniture and acting as masters of ceremonies. The halberdiers wore long tresses to signify their higher position. The first mention of this corps is around 1527, when they were established to clear the roads ahead of the army during a campaign. The dormitory was founded in the 15th century. It was enlarged by the chief architect Davud Ağa in 1587, during the reign of Sultan Murad III. The dormitories are constructed around a main courtyard in the traditional layout of an Ottoman house, with baths and a mosque, as well as recreational rooms such as a pipe-room. On the outside and inside of the complex, many pious foundation inscriptions about the various duties and upkeep of the quarters can be found. In contrast to the rest of the palace, the quarters are constructed by wood, which is painted in red and green.[40]

Imperial Council

The Imperial Council (Dîvân-ı Hümâyûn) building is the chamber in which the ministers of state, council ministers (Dîvân Heyeti), the Imperial Council, consisting of the Grand Vizier (Paşa Kapısı), viziers, and other leading officials of the Ottoman state, held meetings. It is also called Kubbealtı, which means "under the dome", in reference to the dome in the council main hall. It is situated in the northwestern corner of the courtyard next to the Gate of Felicity.

The first Council chambers in the palace were built during the reign of Mehmed II, and the present building dates from the period of Süleyman the Magnificent by the chief architect Alseddin. It has since undergone several changes, was much damaged and restored after the Harem fire of 1665, and according to the entrance inscription it was also restored during the periods of Selim III and Mahmud II.[41]

From the 18th century onwards, the place began to lose its original importance, as state administration was gradually transferred to the Sublime Porte (Bâb-ı Âli) of the Grand Viziers. The last meeting of the Council in the palace chambers was held on Wednesday, August 30, 1876, when the cabinet (Vükela Heyeti) met to discuss the state of Murat V, who had been indisposed for some time.

The council hall has multiple entrances both from inside the palace and from the courtyard. The porch consists of multiple marble and porphyry pillars, with an ornate green and white-coloured wooden ceiling decorated with gold. The floor is covered in marble. The entrances into the hall from outside are in the rococo style, with gilded grills to admit natural light. While the pillars are earlier Ottoman style, the wall paintings and decorations are from the later rococo period. Inside, the Imperial Council building consists of three adjoining main rooms. Two of the three domed chambers of this building open into the porch and the courtyard. The Divanhane, built with a wooden portico at the corner of the Divan Court (Divan Meydani) in the 15th century, was later used as the mosque of the council but was removed in 1916. There are three domed chambers:[42]

- The first chamber where the Imperial Council held its deliberations is the Kubbealtı.

- The second chamber was occupied by the secretarial staff of the Imperial Divan.

- In the adjacent third chamber called Defterhāne, records were kept by the head clerks. The last room also served as a document archive.

On its façade are verse inscriptions, which mention the restoration work carried out in 1792 and 1819, namely under Sultan Selim III and Mahmud II. The rococo decorations on the façade and inside the Imperial Council date from this period. The main chamber Kubbealtı is, however, decorated with Ottoman Kütahya tiles.[42] Three long sofas along the sides were the seats for the officials, with a small hearth in the middle. The small gilded ball that hangs from the ceiling represents the earth. It is placed in front of the sultan's window and symbolises him dispensing justice to the world, as well as keeping the powers of his viziers in check.[43][44]

In the Imperial Council meetings, the political, administrative and religious affairs of the state and important concerns of the citizens were discussed. The Imperial Council normally met four times a week (Saturday, Sunday, Monday and Tuesday) after prayer at dawn.[45] The meetings of the Imperial Council were run according to an elaborate and strict protocol.

Council members such as the Grand Vizier, viziers, chief military officials of the Muslim Judiciary (Kazaskers) of Rumelia and Anatolia, the Minister of Finance or heads of the Treasury (defterdar), the Minister of Foreign Affairs (Reis-ül-Küttab) and sometimes the Grand Müfti (Sheikh ül-İslam) met here to discuss and decide the affairs of state.[45] Other officials who were allowed were the Nişancilar secretaries of the Imperial Council and keepers of the royal monogram (tuğra) and the officials charged with the duty of writing official memoranda (Tezkereciler), and the clerks recording the resolutions.[41]

From the window with the golden grill, the Sultan or the Valide Sultan was able to follow deliberations of the council without being noticed.[45] The window could be reached from the imperial quarters in the adjacent Tower of Justice (Adalet Kulesi).[46] When the sultan rapped on the grill[47] or drew the red curtain, the Council session was terminated, and the viziers were summoned one by one to the Audience Hall (Arz Odası) to present their reports to the sultan.

All the statesmen, apart from the Grand Vizier, performed their dawn prayers in the Hagia Sophia and entered the Imperial Gate according to their rank, passing through the Gate of Salutation and into the divan chamber, where they would wait for the arrival of the Grand Vizier. The Grand Vizier performed his prayers at home, and was accompanied to the palace by his own attendants. On his arrival there, he was given a ceremonial welcome, and before proceeding to the imperial divan, he would approach the Gate of Felicity and salute it as if paying his respects to the gate of the sultan's house. He entered the chamber and took his seat directly under the sultan's window and council commenced. Affairs of the state were generally discussed until noon, when the members of the Council dined in the chambers and after which petitions were heard here.[48] All the members of Ottoman society, men and women of all creeds, were granted a hearing. An important ceremony was held to mark the first Imperial Council of each new Grand Vizier, and also to mark his presentation with the Imperial Seal (Mühr-ü Hümayûn). The most important ceremony took place every three months during the handing out of salaries (ulûfe) to the Janissaries.[49] The reception of foreign dignitaries was normally arranged for the same day, creating an occasion to reflect the wealth and might of the state. Ambassadors were then received by the Grand Vizier in the Council chambers, where a banquet was held in their honour.

Tower of Justice

The Tower of Justice (Adalet Kulesi) is located between the Imperial Council and the Harem. The tower is several stories high and the tallest structure in the palace, making it clearly visible from the Bosphorus as a landmark. The tower was probably originally constructed under Mehmed II and then renovated and enlarged by Suleiman I between 1527-1529.[50]

Sultan Mahmud II rebuilt the lantern of the tower in 1825 while retaining the Ottoman base. The tall windows with engaged columns and the Renaissance pediments evoke the Palladian style.[43]

The tower symbolizes the eternal vigilance of the sultan against injustice. Everyone from afar was supposed to be able to see the tower to feel assured about the sultan's presence. The tower was also used by the sultan for viewing pleasures. The old tower used to have grilled windows, enabling him to see without being seen, adding to the aura of seclusion. The golden window in the Imperial Council is accessible through the Tower of Justice, thus adding to the importance of the symbolism of justice.[51]

Imperial Treasury

The building where the arms and armour are exhibited was originally one of the palace treasuries (Dîvân-ı Hümâyûn Hazinesi / Hazine-ı Âmire). Since there was another ("inner") treasury in the Third Courtyard, this one was also called "outer treasury" (dış hazine).[52] Although it contains no dated inscriptions, its construction technique and plan suggest that it was built at the end of the 15th century during the reign of Süleiman I. It subsequently underwent numerous alterations and renovations. It is a hall built of stone and brick with eight domes,[43] each 5 x 11.40 m.

This treasury was used to finance the administration of the state. The kaftans given as presents to the viziers, ambassadors and residents of the palace by the financial department and the sultan and other valuable objects were also stored here. The janissaries were paid their quarterly wages (called uluefe) from this treasury, which was closed by the imperial seal entrusted to the grand vizier.[52] In 1928, four years after the Topkapı Palace was converted into a museum, its collection of arms and armour was put on exhibition in this building.

During excavations in 1937 in front of this building, remains of a religious Byzantine building dating from the 5th century were found. Since it could not be identified with any of the churches known to have been built on the palace site, it is now known as "the Basilica of the Topkapı Palace" or simply Palace Basilica.

Also located outside the treasury building is a target stone (Nişan Taşı), which is over two metres tall. This stone was erected in commemoration of a record rifle shot by Selim III in 1790. It was brought to the palace from Levend in the 1930s.

Arms collection

The arms collection (Silah Seksiyonu Sergi Salonu), which consists primarily of weapons that remained in the palace at the time of its conversion, is one of the richest assemblages of Islamic arms in the world, with examples spanning 1,300 years from the 7th to the 20th centuries. The palace's collection of arms and armour consists of objects manufactured by the Ottomans themselves, or gathered from foreign conquests, or given as presents. Ottoman weapons form the bulk of the collection, but it also includes examples of Umayyad and Abbasid swords, as well as Mamluk and Persian armour, helmets, swords and axes. A lesser number of European and Asian arms make up the remainder of the collection. Currently on exhibition are some 400 weapons, most of which bear inscriptions.

Gate of Felicity

The Gate of Felicity (Bâbüssaâde or Bab-üs Saadet) is the entrance into the Inner Court (Enderûn), also known as the Third Courtyard, marking the border to the Outer Court or Birûn. The Third Courtyard comprises the private and residential areas of the palace. The gate has a dome supported by lean marble pillars. It represents the presence of the Sultan in the palace.[53] No one could pass this gate without the authority of the Sultan. Even the Grand Vizier was only granted authorisation on specified days and under specified conditions.

The gate was probably constructed under Mehmed II in the 15th century. It was redecorated in the rococo style in 1774 under Sultan Mustafa III and during the reign of Mahmud II. The gate is further decorated with Qur'anic verses above the entrance and tuğras. The ceiling is partly painted and gold-leafed, with a golden ball hanging from the middle. The sides with baroque decorative elements and miniature paintings of landscapes.

The Sultan used this gate and the Divan Meydanı square only for special ceremonies. The Sultan sat before the gate on his Bayram throne on religious, festive days and accession, when the subjects and officials perform their homage standing.[54] The funerals of the Sultan were also conducted in front of the gate.

On either side of this colonnaded passage, under control of the Chief Eunuch of the Sultan’s Harem (called the Bâbüssaâde Ağası) and the staff under him, were the quarters of the eunuchs as well as the small and large rooms of the palace school.

The small, indented stone on the ground in front of the gate marks the place where the banner of Muhammad was unfurled. The Grand Vizier or the commander going to war was entrusted with this banner in a solemn ceremony.

Third Courtyard

Beyond the Gate of Felicity is the Third Courtyard (III. Avlu), also called the Inner Palace (Enderûn Avlusu), which is the heart of the palace, where the sultan spent his days outside the harem.[55] It is a lush garden surrounded by the Hall of the Privy Chamber (Has Oda) occupied by the palace officials, the treasury (which contains some of the most important treasures of the Ottoman age, including the Ottoman miniatures, the Sacred Trusts), the Harem and some pavilions, with the library of Ahmed III in the center. Entry to the Third Courtyard was strictly regulated and off-limits to outsiders.

The Third Courtyard is surrounded by the quarters of the Ağas (pages), boys in the service of the sultan. They were taught the arts, such as music, painting and calligraphy. The best could become Has Odali Ağa (Keepers of the Holy Relics of Muhammad and personal servants of the Sultan), or even become officers or high-ranking officials.

The layout of the Third Courtyard was established by Mehmed II. Its size is roughly comparable to the Second Courtyard.[56] The rigid layout did not allow for any great changes. While Mehmed II would not sleep in the harem, successive sultans after him became more secluded and moved to the more intimate Fourth Courtyard and the harem section.[57] The Hünername miniature from 1584 shows the Third Courtyard and the surrounding outer gardens as it must have appeared following its completion under Mehmed II. It also shows at the bottom the sultan in what looks like a shore pavilion either holding audience or being entertained by courtiers.[58]

Audience Chamber

The Audience Chamber, also known as Audience Hall or Chamber of Petitions (Arz Odası), is right behind the Gate of Felicity to hide the view towards the Third Courtyard. This square building is an Ottoman kiosk, surrounded by a colonnade of 22 columns, supporting the large roof with hanging eaves. Inside is the main throne room with a dome and two smaller adjacent rooms. This audience hall was also called "Inner Council hall" in contrast to the "outer" Imperial Council hall in the Second Courtyard.[59]

It is an old building, dating from the 15th century, and further decorated under Suleiman I. Here the sultan would sit on the canopied throne and personally receive the viziers, officials and foreign ambassadors who presented themselves. According to a contemporary account by envoy Cornelius Duplicius de Schepper in 1533:

The Emperor was seated on a slightly elevated throne completely covered with gold cloth, replete and strewn with numerous precious stones, and there were on all sides many cushions of inestimable value; the walls of the chamber were covered with mosaic works spangled with azure and gold; the exterior of the fireplace of this chamber of solid silver and covered with gold, and at one side of the chamber from a fountain water gushed forth from a wall.[60]

The viziers came here to present their individual reports to the sultan. Depending on their performance and reports, the sultan showed his pleasure by showering them with gifts and high offices, or in the worst case having them strangled by deaf-mute eunuchs.[61] The chamber was thus a place that officials reporting to the sultan entered without knowing if they would leave it again alive.

The most elaborate ceremonies were conducted during the reception of ambassadors who came, escorted by officials, to kiss the hem of the sultan's skirt.[62] The throne was richly decorated during the ceremonies.

The present throne in the form of a baldachin was made by order of Mehmed III. On the lacquered ceiling of the throne, studded with jewels, are foliage patterns accompanied by the depiction of the fight of a dragon, symbol of power, with simurg, a mythical bird. On the throne there is a cover made of several pieces of brocade on which emerald and ruby plaques and pearls are sown.

The ceiling of the chamber was painted in ultramarine blue and studded with golden stars. The tiles that lined the walls were also blue, white and turquoise.[63] The chamber was further decorated with precious carpets and pillows. This was to impress the visitors and hold them in awe of the power and presence of the sultan. The chamber was renovated in 1723 by Sultan Ahmed III and rebuilt in its present form after it was destroyed by fire in 1856 during the rule of Abülmecid I. Today's interior therefore is very different from how it appeared after completion.[64]

Two doors in front lead out into a porch, another one to the back. The two doors in front were for visitors while the third one was for the sultan himself. The embossed inscriptions at the main visitors' door, having the form of the sultan's monogram and containing laudatory words for Sultan Abdülmecid I, date from 1856. The main door is surmounted by an embossed besmele (the Muslim confession of faith "In the Name of God the Compassionate, the Merciful") dating from 1723. The inscription was added during the reign of Sultan Ahmed III. The tile panels on either side of the door were placed during later repair work.

There is a small fountain at the entrance by Suleiman I. The fountain was used not only for refreshment, but could be used to prevent others from overhearing secret conversations in this room.[65][66] The fountain was also a symbol of the sultan; the Persian inscriptions calls him "the fountainhead of generosity, justice and the sea of beneficence."[67]

Gifts presented by ambassadors were placed in front of the large window in the middle of the main facade between the two doors. The Pişkeş Gate to the left (Pişkeş Kapısı, Pişkeş meaning gift brought to a superior) is surmounted by an inscription from the reign of Mahmud II, which dates from 1810.[68]

Behind the Audience Chamber on the eastern side is the Dormitory of the Expeditionary Force.

Dormitory of the Expeditionary Force

The Dormitory of the Expeditionary Force (Seferli Koğuşu) houses the Imperial Wardrobe Collection (Padişhah Elbiseleri Koleksiyonu) with a valuable costume collection of about 2,500 garments, the majority precious kaftans of the Sultans. It also houses a collection of 360 ceramic objects.[69]

The dormitory was constructed under Sultan Murad IV in 1635. The building was restored by Sultan Ahmed III in the early 18th century. The dormitory is vaulted and is supported by 14 columns. Adjacent to the dormitory, located northeast, is the Conqueror's Pavilion.

Conqueror’s Pavilion

The Conqueror’s Pavilion, also called the Conqueror's Kiosk (Fatih Köşkü) and the arcade of the pavilion in front, is one of the pavilions built under Sultan Mehmed II and one of the oldest buildings inside the palace. It was built c. 1460, when the palace was first constructed, and was also used to store works of art and treasure. It houses the Imperial Treasury (Hazine-i Âmire).[70]

The pavilion originally consisted of three rooms, a terrace overlooking the Sea of Marmara, a basement and adjoining hamam, or Turkish bath. It consists of two floors raised on a terrace above the garden, built at the top of the promontory on a cliff with a magnificent view from its porch on the Sea of Marmara and the Bosporus. The lower floor consisted of service rooms, while the upper floor was a suite of four apartments and a large loggia with double arches. The first two rooms are covered with a dome of considerable height. All the rooms open onto the Third Courtyard through a monumental arcade. The colonnaded portico on the side of the garden is connected to each of the four halls by a door of imposing height. The capitals of the imposing capitals are shrunken Ionic in form and date probably from the 18th century. The pavilion was used as the treasury for the revenues from Egypt under Sultan Selim I. Before this period, under Mehmed II and Bayezid II, these apartments must have been the most agreeable rooms in the palace. During excavations in the basement, a small Byzantine baptistery built along a trefoil plan was found.

Imperial Treasury

The Imperial Treasury is a vast collection of works of art, jewelry, heirlooms of sentimental value and money belonging to the Ottoman dynasty. Since the palace became a museum, the same rooms have been used to exhibit these treasures. Most of the objects in the Imperial Treasury consisted of gifts, spoils of war, or pieces produced by palace craftsmen. The Chief Treasurer (Hazinedarbaşı) was responsible for the Imperial Treasury. Upon their accession to the throne, it was customary for the sultans to pay a ceremonial visit to the Treasury.

The objects exhibited in the Imperial Treasury today are a representative selection of its contents, which mainly consist of jeweled objects made of gold and other precious materials. Among the many treasuries that are on exhibition in four adjoining rooms, the first room houses one of the armours of Sultan Mustafa III, consisting of an iron coat of mail decorated with gold and encrusted with jewels, his gilded sword and shield and gilded stirrups. The next display shows several Qur'an covers belonging to the sultans, decorated with pearls. The ebony throne of Murad IV is inlaid with nacre and ivory. The golden Indian music box, with a gilded elephant on top, dates from the 17th century. In other cabinets are looking glasses decorated with rare gems, precious stones, emeralds and cut diamonds.

The second room houses the Topkapı Dagger. The golden hilt is ornamented with three large emeralds, topped by a golden watch with an emerald lid. The golden sheath is covered with diamonds and enamel. In 1747, the Sultan Mahmud I had this dagger made for Nadir Shah of Persia, but the Shah was assassinated in connection with a revolt before the emissary had left the Ottoman Empire's boundaries and so the Sultan retained it. This dagger gained more fame[71] as the object of the heist depicted of the film Topkapi, although The New York Times has written that the palace's greatest artistic treasures are the Ottoman miniatures of the Treasury.[2] Only 100 of the 10,000 miniatures are on display at any one time.[2] In the middle of the second room stands the walnut throne of Ahmed I, inlaid with nacre and tortoise shell, built by Sedekhar Mehmed Agha. Below the baldachin hangs a golden pendant with a large emerald. The next displays show the ostentatious aigrettes of the sultans and their horses, studded with diamonds, emeralds and rubies. A jade bowl, shaped like a vessel, was a present of Czar Nicholas II of Russia.

The most eye-catching jewel in the third room is the Spoonmaker's Diamond, set in silver and surrounded in two ranks with 49 cut diamonds. Legend has it that this diamond was bought by a vizier in a bazaar, the owner thinking it was a worthless piece of crystal. Another, perhaps more likely history for the gem places it among the possessions of Tepedeleni Ali Pasha, confiscated by the Sultan after his execution.[72] Still more fanciful and romantic versions link the diamond's origins with Napoleon Bonaparte's mother Letizia Ramolino (see Spoonmaker's Diamond page).

Among the exhibits are two large golden candleholders, each weighing 48 kg and mounted with 6,666 cut diamonds, a present of Sultan Abdülmecid I to the Kaaba in the holy city of Mecca. They were brought back to Istanbul shortly before the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the loss of control over Mecca. The golden ceremonial Bayram throne, mounted with tourmalines, was made in 1585 by order of the vizier Ibrahim Pasha and presented to Sultan Murad III. This throne would be set up in front of the Gate of Felicity on special audiences.

The throne of Sultan Mahmud I is the centerpiece of the fourth room. This golden throne in Indian style, decorated with pearls and emeralds, was a gift of the Persian ruler Nader Shah in the 18th century. Another exhibit shows the forearm and the hand of St. John the Baptist, set in a golden covering. Several displays show an assembly of flintlock guns, swords, spoons, all decorated with gold and jewels. Of special interest is the golden shrine that used to contain the cloak of Mohammed.

Miniature and Portrait Gallery

Adjacent to the north of the Imperial Treasury lays the pages dormitory, which has been turned into the Miniature and Portrait Gallery (Müzesi Müdüriyeti). On the lower floor is a collection of important calligraphies and miniatures. In the displays, one can see old and very precious Qur'ans (12th to 17th centuries), hand-painted and hand-written in Kufic, and also a Bible from the 4th century, written in Arabic. A priceless item of this collection is the first world map by the Turkish admiral Piri Reis (1513). The map shows parts of the western coasts of Europe and North Africa with reasonable accuracy, and the coast of Brazil is also easily recognizable. The upper part of the gallery contains 37 portraits of different sultans, most of which are copies since the original paintings are too delicate to be publicly shown. The portrait of Mehmed II was painted by the Venetian painter Gentile Bellini. Other precious Ottoman miniature paintings that are either kept in this gallery, the palace library or in other parts are the Hünername, Sahansahname, the Sarayı Albums, Siyer-ı Nebi, Surname-ı Hümayun, Surname-ı Vehbi, and the Süleymanname among many others.[73]

Enderûn Library (Library of Ahmed III)

The Neo-classical Enderûn Library (Enderûn Kütüphanesi), also known as "Library of Sultan Ahmed III" (III. Ahmed Kütüphanesi), is located directly behind the Audience Chamber (Arz Odası) in the centre of the Third Court. It was built on the foundations of the earlier Havuzlu kiosk by the royal architect Mimar Beşir Ağa in 1719 on orders of Ahmed III for use by officials of the royal household. The colonnade of this earlier kiosk now probably stands in front of the present Treasury.

The library is a beautiful example of Ottoman architecture of the 18th century.[citation needed] The exterior of the building is faced with marble. The library has the form of a Greek cross with a domed central hall and three rectangular bays. The fourth arm of the cross consists of the porch, which can be approached by a flight of stairs on either side. Beneath the central arch of the portico is an elaborate drinking fountain with niches on each side. The building is set on a low basement to protect the precious books of the library against moisture.

The walls above the windows are decorated with 16th- and 17th-century İznik tiles of variegated design. The central dome and the vaults of the rectangular bays have been painted. The decoration inside the dome and vaults are typical of the so-called Tulip period, which lasted from 1703 to 1730. The books were stored in cupboards built into the walls. The niche opposite the entrance was the private reading corner of the sultan.

The library contained books on theology, Islamic law and similar works of scholarship in Ottoman Turkish, Arabic and Persian. The library collection consisted of more than 3,500 manuscripts. Some are fine examples of inlay work with nacre and ivory. Today these books are kept in the Mosque of the Ağas (Ağalar Camii), which is located to the west of the library. One of the most important items there is the Topkapi manuscript, a copy of the Qur'an from the time of the third Caliph Uthman Ibn Affan.

Mosque of the Ağas

The Mosque of the Ağas (Ağalar Camii) is the largest mosque in the palace. It is also one of the oldest constructions, dating from the 15th century during the reign of Mehmed II. The Sultan, the ağas and pages would come here to pray. The mosque is aligned in a diagonal line in the courtyard to make the minbar face Mecca. In 1928 the books of the Enderûn Library, among other works, were moved here as the Palace Library (Sarayı Kütüphanesi), housing a collection of about 13,500 Turkish, Arabic, Persian and Greek books and manuscripts, collected by the Ottomans. Located next to the mosque to the northeast is the Imperial Portraits Collection.

Dormitory of the Royal Pages

The Dormitory of the Royal Pages (Hasoda Koğuşu) houses the Imperial Portraits Collection (Padişah Portreleri Sergi Salonu) was part of the Sultan's chambers. The painted portraits depict all the Ottoman sultans and some rare photographs of the later ones, the latter being kept in glass cases. The room is air-conditioned and the temperature regulated and monitored to protect the paintings. Since the sultans rarely appeared in public, and to respect Islamic sensitivity to artistic depictions of people, the earlier portraits are idealisations. Only since the reforms of the moderniser Mahmud II have realistic portraits of the rulers been made. An interesting feature is a large painted family tree of the Ottoman rulers. The domed chamber is supported by pillars, some of Byzantine origin since a cross is engraved on one of them.

Privy Chamber

The Privy Chamber houses the Chamber of the Sacred Relics (Kutsal Emanetler Dairesi), which includes the Pavilion of the Holy Mantle. The chamber was constructed by Sinan under the reign of Sultan Murad III. It used to house offices of the Sultan.

It houses what are considered to be "the most sacred relics of the Muslim world":[2] the cloak of Muhammad, two swords, a bow, one tooth, a hair of his beard, his battle sabres, an autographed letter and other relics[71] which are known as the Sacred Trusts. Several other sacred objects are on display, such as the swords of the first four Caliphs, The Staff of Moses, the turban of Joseph and a carpet of the daughter of Mohammed. Even the Sultan and his family were permitted entrance only once a year, on the 15th day of Ramadan, during the time when the palace was a residence. Now any visitor can see these items, although in very dim light to protect the relics,[71] and many Muslims make a pilgrimage for this purpose.

The Arcade of the Chamber of the Holy Mantle was added in the reign of Murad III, but was altered when the Circumcision Room was added. This arcade may have been built on the site of the Temple of Poseidon that was transformed before the 10th century into the Church of St. Menas.[74]

The Privy Chamber was converted into an accommodation for the officials of the Mantle of Felicity in the second half of the 19th century by adding a vault to the colonnades of the Privy Chamber in the Enderun Courtyard.

Harem

.svg.png)

The Imperial Harem (Harem-i Hümayûn) occupied one of the sections of the private apartments of the sultan; it contained more than 400 rooms.[75] The harem was home to the sultan's mother, the Valide Sultan; the concubines and wives of the sultan; and the rest of his family, including children; and their servants.[76] The harem consists of a series of buildings and structures, connected through hallways and courtyards. Every service team and hierarchical group residing in the harem had its own living space clustered around a courtyard. The number of rooms is not determined, with probably over 100,[77] of which only a few are open to the public. These apartments (Daires) were occupied respectively by the harem eunuchs, the Chief Harem Eunuch (Darüssaade Ağası), the concubines, the queen mother, the sultan's consorts, the princes and the favourites. There was no trespassing beyond the gates of the harem, except for the sultan, the queen mother, the sultan's consorts and favourites, the princes and the concubines as well as the eunuchs guarding the harem. The harem wing was only added at the end of the 16th century. Many of the rooms and features in the Harem were designed by Mimar Sinan. The harem section opens into the Second Courtyard (Divan Meydanı), which the Gate of Carriages (Arabalar Kapısı) also opens to. The structures expanded over time towards the Golden Horn side and evolved into a huge complex. The buildings added to this complex from its initial date of construction in the 15th century to the early 19th century capture the stylistic development of palace design and decoration. Parts of the harem were redecorated under the sultans Mahmud I and Osman III in an Italian-inspired Ottoman Baroque style. These decorations contrast with those of the Ottoman classical age.

Gate of Carts / Domed Cupboard Chamber

The entrance gate from the Second Courtyard is the Gate of Carts (Arabalar Kapısı), which leads into the Domed Cupboard Room (Dolaplı Kubbe). This place was built as a vestibule to the harem in 1587 by Murad III. The harem treasury worked here. In its cupboards, records of deeds of trust were kept, administered by the Chief Harem Eunuch. This treasury stored money from the pious foundations of the harem and other foundations, and financial records of the sultans and the imperial family.

Hall of the Ablution Fountain

The Hall of the Ablution Fountain, also known as "Sofa with Fountain," (Şadirvanli Sofa) was renovated after the Harem fire of 1666. This second great fire took place on 24 July 1665. This space was an entrance hall into the harem, guarded by the harem eunuchs. The Büyük Biniş and the Şal Kapısı, which connected the Harem, the Privy Garden, the Mosque of the Harem Eunuchs and the Tower of Justice from where the sultan watched the deliberations of the Imperial Council, led to this place. The walls are revetted with 17th-century Kütahya tiles. The horse block in front of the mosque served the sultan to mount his horse and the sitting benches were for the guards. The fountain that gives the space its name was moved and is now in the pool of the Privy Chamber of Murad III.

On the left is the small mosque of the black eunuchs. The tiles in watery green, dirty white and middle blue all date from the 17th century (reign of Mehmed IV). Their design is of a high artistic level but the execution is of minor quality compared to 16th-century tiles, and the paint on these tiles blurs.[2]

Courtyard of the Eunuchs

Another door leads to the Courtyard of the (Black) Eunuchs (Harem Ağaları Taşlığı), with their apartments on the left side. At the end of the court is the apartment of the black chief eunuch (Kızlar Ağası), the fourth high-ranking official in the official protocol. In between is the school for the imperial princes, with precious tiles from the 17th and 18th centuries and gilded wainscoting. At the end of the court is the main gate to the harem (Cümle Kapısi). The narrow corridor on the left side leads to the apartments of the odalisques (white slaves given as a gift to the sultan).

Many of the eunuchs’ quarters face this courtyard, which is the first one of the Harem, since they also acted as guards under the command of the Chief Harem Eunuch. The spaces surrounding this courtyard were rebuilt after the great fire of 1665. The complex includes the dormitory of the Harem eunuchs behind the portico, the quarters of the Chief Harem Eunuch (Darüssaade Ağası) and the School of Princes as well as the Gentlemen-in-Waiting of the Sultan (Musahipler Dairesi) and the sentry post next to it. The main entrance gate of the Harem and the gate of the Kuşhane connected the Enderûn court leads out into the Kuşhane door.

The dormitories of the Harem eunuchs (Harem Ağaları Koğuşu) date to the 16th century. They are arranged around an inner courtyard in three storys. The inscription on the facade of the dormitory includes the deeds of trust of the Sultans Mustafa IV, Mahmud II and Abdül Mecid I dating from the 19th century. The rooms on the upper stories were for novices and those below overlooking the courtyard were occupied by the eunuchs who had administrative functions. There is a monumental fireplace revetted with the 18th-century Kütahya tiles at the far end. The Chief Harem Eunuch's apartment (Darüssaade Ağasi Dairesi) adjacent to the dormitory contains a bath, living rooms and bedrooms. The school room of the princes under the control of the Chief Harem eunuch was on the upper story. The walls were revetted with 18th-century European tiles with baroque decorations.

Harem main entrance

The main entrance (Cümle Kapisi) separates the harem in which the family and the concubines of the sultan resided from the Courtyard of the Eunuchs. The door leads out into the sentry post (Nöbet Yeri) to which the three main sections of the harem are connected. The door on the left of the sentry post leads through the Passage of the Concubines to the Court of the Concubines (Kadınefendiler Taşlığı). The door in the middle leads to the Court of the Queen Mother (Valide Taşlığı) and the door to the right leads through the Golden Road (Altınyol) to the sultan's quarters. The large mirrors in this hall date from the 18th century.

Courtyard of the Queen Mother

After the main entrance and before turning to the Passage of Concubines is the Courtyard of the Queen Mother.[78]

Passage of Concubines

The Passage of Concubines (Cariye Koridoru) leads into the Courtyard of the Sultan's Chief Consorts and Concubines. On the counters along the passage, the eunuchs placed the dishes they brought from the kitchens in the palace.

Courtyard of the Sultan's Consorts and the Concubines

The Courtyard of the Sultan's Consorts and the Concubines (Kadın Efendiler Taşlığı / Cariye Taşlığı) was constructed at the same time as the courtyard of the eunuchs in the middle of the 16th century. It underwent restoration after the 1665 fire and is the smallest courtyard of the Harem. The porticoed courtyard is surrounded by baths (Cariye Hamamı), a laundry fountain, a laundry, dormitories, the apartments of the Sultan's chief consort and the apartments of the stewardesses (Kalfalar Dairesi). The three independent tiled apartments with fireplaces overlooking the Golden Horn were the quarters where the consorts of the Sultan lived. These constructions covered the site of the courtyard in the late 16th century. At the entrance to the quarters of the Queen Mother, wall frescoes from the late 18th century depict landscapes, reflecting the western influence. The staircase, called the "Forty Steps" (Kirkmerdiven), leads to the Hospital of the Harem (Harem Hastanesi), the dormitories of the concubines at the basement of the Harem and Harem Gardens.

Apartments of the Queen Mother

The Apartments of the Queen Mother (Valide Sultan Dairesi), together with the apartments of the sultan, form the largest and most important section in the harem.[79] It was constructed after the Queen Mother moved into the Topkapı Palace in the late 16th century from the Old Palace (Eski Saray), but had to be rebuilt after the fire of 1665 between 1666-1668.[80] Some rooms, such as the small music room, have been added to this section in the 18th century. Only two of these rooms are open to the public: the dining room[81] with, in the upper gallery, the reception room and her bedroom with,[81] behind a lattice work, a small room for prayer.[82] On the lower stories of the apartments are the quarters of the concubines, while the upper story rooms are those of the Queen Mother and her ladies-in-waiting (kalfas). The apartments of the Queen Mother are connected by a passage, leading into the Queen Mother's bathroom, to the quarters of the sultan.

These are all enriched with blue-and-white or yellow-and-green tiles with flowery motifs and İznik porcelain from the 17th century. The panel representing Mecca or Medina, signed by Osman İznikli Mehmetoğlu, represents a new style in İznik tiles. The paintwork with panoramic views in the upper rooms is in the Western European style of the 18th and 19th centuries.[80][83]

Situated on top of the apartments of the Queen Mother are the apartments of Mihirisah in the rococo style. Leading from the apartments to the baths lays the apartment of Abdül Hamid I. Close to that is Selim's III love chamber constructed in 1790. A long, narrow corridor connects this to the kiosk of Osman III dated to 1754.

Baths of the Sultan and the Queen Mother

The next rooms are the Baths of the Sultan and the Queen Mother (Hünkâr ve Vâlide Hamamları). This double bath dates from the late 16th century and consists of multiple rooms.[83] It was redecorated in the rococo style in the middle of the 18th century. Both baths present the same design, consisting of a caldarium, a tepidarium and a frigidarium.[83] Each room either has a dome, or the ceilings are at some point glassed in a honeycomb structure to let the natural sunlight in. The floor is clad in white and grey marble. The marble tub with an ornamental fountain in the caldarium and the gilded iron grill are characteristic features. The golden lattice work was to protect the bathing sultan or his mother from murder attempts. The sultan's bath was decorated by Sinan with high-quality İznik polychrome tiles. But much of the tile decoration of the harem, from structures damaged by the fire of 1574, was recycled by Sultan Ahmed I for decoration in his new Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul. The walls are now either clad in marble or white-washed.

Imperial Hall

The Imperial Hall (Hünkâr Sofası), also known as the Imperial Sofa, Throne Room Within or Hall of Diversions, is a domed hall in the Harem, believed to have been built in the late 16th century. It has the largest dome in the palace. The hall served as the official reception hall of the sultan as well as for the entertainment of the Harem. Here the sultan received his confidants, guests, his mother, his first wife (Hasseki), consorts, and his children. Entertainments, paying of homage during religious festivals, and wedding ceremonies took place here in the presence of the members of the dynasty.[84]

After the Great Harem Fire of 1666, the hall was renovated in the rococo style during the reign of Sultan Osman III. The tile belt surrounding the walls bearing calligraphic inscriptions were revetted with 18th-century blue-and-white Delftware and mirrors of Venetian glass. But the domed arch and pendantives still bear classical paintings dating from the original construction.[85]

In the hall stands the sultan's throne. The gallery was occupied by the consorts of the sultan, headed by the Queen Mother. The gilded chairs are a present of Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, while the clocks are a gift of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. A pantry, where musical instruments are exhibited, opens to the Imperial Hall, which provides access into the sultan's private apartments.

A secret door behind a mirror allowed the sultan a safe passage. One door admits to the Queen Mother’s apartments, another to the sultan's hammam. The opposite doors lead to the small dining chamber (rebuilt by Ahmed III) and the great bedchamber,[86] while the other admits to a series of ante-chambers, including the room with the fountain (Çeşmeli Sofa), which were all retiled and redecorated in the 17th century.

Privy Chamber of Murat III

The Privy Chamber of Murat III (III. Murad Has Odası) is the oldest and finest surviving room in the harem, having retained its original interior. It was a design of the master architect Sinan and dates from the 16th century.[86] Its dome is only slightly smaller than that of the Throne Room. Its hall has one of the finest doors of the palace and leads past the wing of the crown princes (Kafes). The room is decorated with blue-and-white and coral-red İznik tiles.[86] The rich floral designs are framed in thick orange borders of the 1570s. A band of inscriptional tiles runs around the room above the shelf and door level. The large arabesque patterns of the dome have been regilded and repainted in black and red. The large fireplace with gilded hood (ocak) stands opposite a two-tiered fountain (çeşme), skilfully decorated in coloured marble. The flow of water was meant to prevent any eavesdropping,[71] while providing a relaxed atmosphere to the room. The two gilded baldachin beds date from the 18th century.

Privy Chamber of Ahmed I

On the other side of the great bedchamber there are two smaller rooms: first the Privy Chamber of Ahmed I (I. Ahmed Has Odası), richly decorated with İznik glazed tiles.[87] The cabinet doors, the window shutters, a small table and a Qur'an lectern are decorated with nacre and ivory.

Privy Chamber of Ahmed III

Next to it is the small but very colourful Privy Chamber of Ahmed III (III. Ahmed Has Odası) with walls painted with panels of floral designs and bowls of fruit and with an intricate tiles fireplace (ocak).[88] This room is therefore also known as the Fruit Room (Yemis Odası) and was probably used for dining purposes.

Twin Kiosk / Apartments of the Crown Prince

The Twin Kiosk / Apartments of the Crown Prince (Çifte Kasırlar / Veliahd Dairesi) consists of two privy chambers built in the 17th century, at different times. The building is connected to the palace and consists of only one storey built on an elevated platform to give a better view from inside and shield views from the outside.

The interior consists of two large rooms, dating from the reign of Sultan Murat III, but are more probably from the reign of Ahmed I.[89] The ceiling is not flat but conical in the kiosk style, evoking the traditional tents of the early Ottomans. As in tents, there is no standing furniture but sofas set on the carpeted floor on the side of the walls for seating. These chambers represent all the details of the classical style used in other parts of the palace. The pavilion has been completely redecorated, and most of the Baroque woodwork has been removed. The decorative tiles, reflecting the high quality craftsmanship of the İznik tile industry of the 17th century,[90] were removed in accordance with the original concept and replaced with modern copies. The paintwork of the wooden dome is still original and is an example of the rich designs of the late 16th/early 17th centuries. The fireplace in the second room has a tall, gilded hood and has been restored to its original appearance.[91] The window shutters next to the fireplace are decorated with nacre intarsia. The windows in coloured glass look out across the high terrace and the garden of the pool below. The spigots in these windows are surrounded with red, black and gold designs.

The crown prince (Şehzadeler) lived here in seclusion; therefore, the apartments were also called kafes (cage). The crown prince and other princes were trained in the discipline of the Ottoman Harem until they reached adulthood. Afterwards, they were sent as governors to Anatolian provinces, where they were further trained in the administration of state affairs. From the beginning of the 17th century onward, the princes lived in the Harem, which started to have a voice in the palace administration. The Twin Kiosk was used as the privy chamber of the crown prince from the 18th century onward.

Courtyard of the Favourites

The Courtyard of the Favourites (Gözdeler / Mabeyn Taşlığı ve Dairesi) forms the last section of the Harem and overlooks a large pool and the Boxwood Garden (Şimşirlik Bahçesi).[91] The courtyard was expanded in the 18th century by the addition of the Interval (Mabeyn) and Favourites (İkballer) apartments. The apartment of the Sultan's Favourite Consort along with the Golden Road (Altın Yol) and the Mabeyn section at the ground floor also included the Hall with the Mirrors. This was the space where Abül Hamid I lived with his harem.[92] The wooden apartment is decorated in the rococo style.

The favourites of the sultan (Gözdeler / İkballer) were conceived as the instruments of the perpetuation of the dynasty in the harem organisation. When the favourites became pregnant they assumed the title and powers of the official consort (Kadınefendi) of the sultan.

Golden Road

The Golden Road (Altınyol) is a narrow passage that forms the axis of the Harem, dating from the 15th century. It extends between the Courtyard of the Harem Eunuch (Harem Ağaları Taşlığı) and the Privy Chamber (Has Oda). The sultan used this passage to pass to the Harem, the Privy Chamber and the Sofa-i Hümâyûn, the Imperial terrace. The Courtyard of the Queen Mother (Valide Sultan Taşlığı’), the Courtyard of the Chief Consort of the Sultan (Baş Haseki), the apartments of the Princes (Şehzadegân Daireleri), and the apartments of the Sultan (Hünkâr Dairesi) open to this passage. The walls are painted a plain white colour. It is believed that the attribute "golden" is due to the sultan's throwing of golden coins to be picked up by the concubines at festive days, although this is disputed by some scholars.[93]

Aviary / Harem Gate

Until the late 19th century, there had been a small inner court in this corner of the Enderûn Courtyard. This court led through the Kuşhane Gate into the harem. Today this is the gate from which the visitors exit from the Harem. Birds were raised for the sultan's table in the buildings around the gate. On the inscription over the Kuşhane door one reads that Mahmud I had the kitchen of the Kuşhane repaired. The balcony of the aviary facing the Harem Gate was constructed during repair work in 1916. The building's facade resembles traditional aviaries.

Fourth Courtyard

The Fourth Courtyard (IV. Avlu), also known as the Imperial Sofa (Sofa-ı Hümâyûn), was more of an innermost private sanctuary of the sultan and his family, and consists of a number of pavilions, kiosks (köşk), gardens and terraces. It was originally a part of the Third Courtyard but recent scholars have identified it as more separate to better distinguish it.[94]

Circumcision Room

In 1640 Sultan Ibrahim I added the Circumcision Room (Sünnet Odası), a summer kiosk (Yazlik Oda) dedicated to the circumcision of young princes, which is a religious tradition in Islam for cleanliness and purity. Its interior and exterior are decorated with a mixed collection of rare recycled tiles such as the blue tiles with flower motifs at the exterior. The most important of these are the blue and white tile panels influenced by far-eastern ceramics on the chamber facade, dated 1529. These once embellished ceremonial buildings of Sultan Suleiman I, such as the building of the Council Hall and the Inner Treasury (both in the Second Courtyard) and the Throne Room (in the Third Courtyard). They were moved here out of nostalgia and reverence for the golden age of his reign. These tiles then served as prototypes for the decoration of the Yerevan and Baghdad kiosks. The room itself is symmetrically proportioned and relatively spacious for the palace, with windows, each with a small fountain. The windows above contain some stained-glass panels. On the right side of the entrance stands a fireplace with a gilded hood. Sultan Ibrahim also built the arcaded roof around the Chamber of the Holy Mantle and the upper terrace between this room and the Baghdad kiosk.

The royal architect Hasan Ağa under Sultan Murat IV constructed during 1635-1636 the Yerevan Kiosk (Revan Köşkü) and in 1638-1639 the Baghdad Kiosk (Bağdat Köşkü) to celebrate the Ottoman victories at Yerevan and Baghdad. Both contain most of their original decoration,[71] with projecting eaves, a central dome and interior with recessed cupboards and woodwork with inlaid nacre tesserae. Both are based on the classical four-iwan plan with sofas filling the rectangular bays.

Revan Kiosk

_-_Foto_G._Dall'Orto_27-5-2006.jpg)

The Revan Kiosk (Revan Köşkü) served as a religious retreat of 40 days. It is a rather small pavilion with a central dome and three apses for sofas and textiles.[71] The fourth wall contains the door and a fireplace. The wall facing the colonnade is set with marble, the other walls with low-cost İznik blue-and-white tiles, patterned after those of a century earlier.

Baghdad Kiosk

The Baghdad Kiosk (Bağdad Köşkü) is situated on the right side of the terrace with a fountain. It was built to commemorate the Baghdad Campaign of Murad IV after 1638.

It closely resembles the Yerevan Kiosk. The three doors to the porch are located between the sofas. The façade is covered with marble, strips of porphyry and verd antique. The marble panelling of the portico is executed in Cairene Mamluk style. The interior is an example of an ideal Ottoman room.[71] The recessed shelves and cupboards are decorated with early 16th-century green, yellow and blue tiles. The blue-and-white tiles on the walls are copies of the tiles of the Circumcision Room, right across the terrace. With its tiles dating to the 17th century, mother-of-pearl, tortoise-shell decorated cupboard and window panels, this pavilion is one of the last examples of the classical palace architecture.

The doors have very fine inlay work. On the right side of the entrance is a fireplace with a gilded hood. In the middle of the room is a silver 'mangal' (charcoal stove), a present of King Louis XIV of France. From the mid-18th century onwards, the building was used as the library of the Privy Chamber.

İftar Kiosk

The gilded İftar Pavilion, also known as İftar Kiosk or İftar bower (İftariye Köşkü or İftariye Kameriyesi) offers a view on the Golden Horn and is a magnet for tourists today for photo opportunities. Its ridged cradle vault with the gilded roof was a first in Ottoman architecture with echoes of China and India. The sultan is reported to have had the custom to break his fast under this bower during the fasting month of ramadan after sunset. Some sources mention this resting place as the "Moonlit Seat". Special gifts like the showering of gold coins to officials by the sultan also sometimes occurred here. The marbled terrace gained its current appearance during the reign of Sultan Ibrahim (1640–48).

Terrace Kiosk

The rectilinear Terrace Kiosk (Sofa Köşku / Merdiven Başı Kasrı), also erroneously known as Kiosk of Kara Mustafa Pasha (Mustafa Paşa Köşkü), was a belvedere built in the second half of the 16th century. It was restored in 1704 by Sultan Ahmed III and rebuilt in 1752 by Mahmud I in the Rococo style. It is the only wooden building in the innermost part of the palace. It consists of rooms with the backside supported by columns.

The kiosk consists of the main hall called Divanhane, the prayer room (Namaz Odası or Şerbet Odası) and the Room for Sweet Fruit Beverages. From the kiosk the sultan would watch sporting events in the garden and organised entertainments. This open building with large windows was originally used as a restroom and later, during the Tulip era (1718–1730), as a lodge for guests. It is situated next to the Tulip Garden.

Tower of the Head Tutor / Chamber of the Chief Physician

The square Tower of the Head Tutor (Başlala Kulesi), also known as the Chamber of the Chief Physician and court drugstore (Hekimbaşı Odası ve ilk eczane), dates from the 15th century, and is the oldest building in the Fourth Courtyard. It was built as a watch tower, probably during the time of Mehmed II. It has few windows, and its walls are almost two metres thick. The physician had his private chamber at the top, while below was a store for drugs and medicine.