Tom Thomson

| Tom Thomson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Thomas John Thomson August 5, 1877 Claremont, Ontario |

| Died |

July 8, 1917 (aged 39) Canoe Lake, Algonquin Park, Ontario |

Thomas John "Tom" Thomson (August 5, 1877 – July 8, 1917) was an influential Canadian artist of the early 20th century. He directly influenced a group of Canadian painters that would come to be known as the Group of Seven, and though he died before they formally formed, he is sometimes incorrectly credited as being a member of the group itself. Thomson died under mysterious circumstances, which added to his mystique.

Personal life

Thomas John "Tom" Thomson was born near Claremont, Ontario to John and Margaret Thomson and grew up in Leith, Ontario, near Owen Sound.[1] In 1899, he entered a machine shop apprenticeship at an iron foundry owned by William Kennedy, a close friend of his father. He was fired from his apprenticeship by a foreman who complained of Thomson's habitual tardiness. Also in 1899, he volunteered to fight in the Second Boer War, but was turned down because of a medical condition.[citation needed] Thomson was reputed to have been refused entry into the Canadian Expeditionary Force for service in the First World War also.[citation needed] He served as a fire ranger in Algonquin Park during this time.[2] In 1901, he enrolled in a business college in Chatham, Ontario, but dropped out eight months later to join his older brother, George Thomson, who was operating a business school in Seattle. There he met and had a brief summer romance with Alice Elinor Lambert. In 1904, he returned to Canada, and may have studied with William Cruikshank, 1905–1906.[2] In 1907, Thomson joined Grip Ltd., an artistic design firm in Toronto, where many of the future members of the Group of Seven also worked.

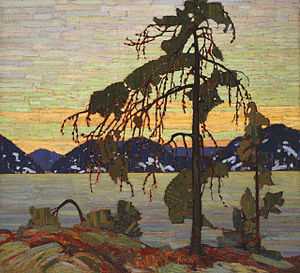

Thomson first visited Algonquin Park in 1912. Thereafter he often traveled around Ontario with his colleagues, especially to the wilderness of Ontario, which was to be a major source of inspiration for him. In 1912 he began working, along with other artists who would go on to form the Group of Seven after his death, at Rous and Mann Press, but left the following year to work as a full-time artist. He first exhibited with the Ontario Society of Artists in 1913, and became a member in 1914 when the National Gallery of Canada purchased one of his paintings. He would continue to exhibit with the Ontario Society until his death. For several years he shared a studio and living quarters with fellow artists, before taking up residence on Canoe Lake. Beginning in 1914 he worked intermittently as a fire fighter, ranger, and guide in Algonquin Park, but found that such work did not allow enough time for painting.[3] During the next three years, he produced many of his most famous works, including The Jack Pine, The West Wind and The Northern River.

Paintings

-

Tom Thomson's Forest Undergrowth

-

Tom Thomson's The Jack Pine 1916–17

-

Tom Thomson's Pine Island, Georgian Bay

-

Tom Thomson's April in Algonquin Park 1917

-

Tom Thomson's The West Wind

Art and technique

Thomson was largely self-taught. He was employed as a graphic designer with Toronto's Grip Ltd., an experience which honed his draughtsmanship. Although he began painting and drawing at an early age, it was only in 1912, when Thomson was well into his thirties, that he began to paint seriously. His first trips to Algonquin Park inspired him to follow the lead of fellow artists in producing oil sketches of natural scenes on small, rectangular panels for easy portability while travelling. Between 1912 and his death in 1917, Thomson produced hundreds of these small sketches, many of which are now considered works in their own right, and are housed in such galleries as the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

Many of Thomson's major paintings, including Northern River, The Jack Pine, and The West Wind, began as sketches before being expanded into large oil paintings at Thomson's "studio"—an old utility shack with a wood-burning stove on the grounds of the Studio Building, an artist's enclave in Rosedale, Toronto. Although Thomson sold few of these paintings during his lifetime, they formed the basis of posthumous exhibitions, including one at Wembley in London, that eventually brought international attention to his work.

Thomson peaked creatively between 1914 and 1917. He was aided by the patronage of Toronto physician James MacCallum, who enabled Thomson's transition from graphic designer to professional painter.

Although the Group of Seven was not founded until after Thomson's death, his work is sympathetic to that of group members A. Y. Jackson, Frederick Varley, and Arthur Lismer. These artists shared an appreciation for rugged, unkempt natural scenery, and all used broad brush strokes and a liberal application of paint to capture the stark beauty and vibrant colour of the Ontario landscape.

Thomson's art bears some stylistic resemblance to the work of European post-impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne, whose work he may have known from books or visits to art galleries. Other key influences were the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, styles with which he would have been familiar from his work in the graphic arts.

For artist and Thomson biographer Harold Town, the brevity of Thomson's career hinted at an artistic evolution never fully realized. He cites the oil painting Unfinished Sketch as "the first completely abstract work in Canadian art," a painting that, whether or not it was intended as a purely non-objective work, presages the innovations of Abstract expressionism.[4]

Death

Thomson disappeared during a canoeing trip on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park on July 8, 1917, and his body was discovered in the lake eight days later. The official cause of death was accidental drowning, but there were questions about how he actually died.[citation needed] Thomson's body was examined by Dr. Goldwin Howland, and interred in Mowat Cemetery, near Canoe Lake, the day after his body was discovered. Under the direction of his older brother, George Thomson, the body was exhumed two days later and re-interred in the family plot beside the Leith Presbyterian Church on July 21.

In 1935, Blodwen Davies published the first exploration of Thomson's death outside of newspaper accounts from the time of Thomson's death.[5] As this was a self-published edition of 500 copies, her doubts about the official decision of cause of death did not receive wide attention. An edited version of her text was published posthumously in 1967.[6]

In 1970, Judge William Little published a book, The Tom Thomson Mystery, recounting how—in 1956—he and three friends dug up Thomson's original gravesite, in Mowat Cemetery on Canoe Lake.[7] They believed that remains they found were Thomson's. In the fall of 1956, medical investigators determined that the body was that of an unidentified Aboriginal.

Since the publication of The Tom Thomson Mystery, theories have proliferated regarding Thomson's cause of death, including suicide and murder. Proponents of these theories suggest that Thomson may have committed suicide over a woman who holidayed at Canoe Lake being pregnant with his child, or out of despondence over his lack of artistic recognition. Others have suggested that Thomson was in a fatal fight with one of two men who were living at Canoe Lake, or killed by poachers in the park.

In 2007, the Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History project launched Death On A Painted Lake: The Tom Thomson Tragedy, a book-length, bilingual (English/French) web site featuring a selection of over fifty transcribed primary and secondary documents related to Thomson's death, including documents never before made public, such as Blodwen Davies' 1931 request to the Ontario Attorney General for opening of Thomson's Algonquin Park burial site.

Relying significantly on the site's transcriptions (see author's 'Acknowledgements'), Roy MacGregor has described a 2009 examination of records of the 1956 remains unearthed by William Little (the remains have been reburied or lost) and concluded that the body was actually Thomson's, indicating "that Thomson never left Canoe Lake."[8]

In an essay entitled, "The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson," published in 2011, Gregory Klages describes how testimony and theories regarding Thomson's death have evolved since 1917.[9] Assessing the secondary accounts against the primary evidence, Klages concludes the most plausible explanation for Thomson's death is consistent with the official assessment of 'accidental drowning'. Historians Kathleen Garay and Christl Verduyn state, "Klages' forensic archival sleuthing does provide for the first time some degree of certainty regarding this event."[10]

Journalist Roy MacGregor's 1980 novel Shorelines (reissued in 2002 as Canoe Lake) is a fictional interpretation of Thomson's death. Neil Lehto's Algonquin Elegy (2005) is a 'historical fiction' focusing on Thomson's death. Several books of poetry using Thomson's death as inspiration or a reference point have been published. Several songs referencing Thomson's death—by Canadian artists such as Alex Sinclair and the Tragically Hip—have also been recorded.

Legacy and influence

Since his death, Thomson's work has grown in value and popularity. In 2002, the National Gallery of Canada staged a major exhibition of his work, giving Thomson the same level of prominence afforded Picasso, Renoir, and the Group of Seven in previous years. In recent decades, the increased value of Thomson's work has led to the discovery of numerous forgeries of his work on the market.

In September 1917, the artists James E. H. MacDonald and John W. Beatty, assisted by area residents, erected a memorial cairn at Hayhurst Point on Canoe Lake, where Thomson died. The cost was paid by MacCallum. It can be accessed by boat. In the summer of 2004 another historical marker honouring Thomson was moved from its previous location nearer the centre of Leith to the graveyard in which Thomson is now buried. In 1967, the Tom Thomson Art Gallery[11] opened in Owen Sound. Numerous examples of his work are also on display at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario. Thomson's influence can be seen in the work of later Canadian artists, including Emily Carr, Goodridge Roberts, Harold Town, and Joyce Wieland.

References

Books on Thomson's art include the 1977 The Silence and the Storm by Harold Town and David Silcox, and several short coffee table books by former Art Gallery of Ontario curator, Joan Murray. The 2002 book, Tom Thomson, created to accompany the National Gallery of Canada and Art Gallery of Ontario exhibition of Thomson's work, ranks as the most in-depth survey of Thomson's oeuvre.

During the 1970s, Joyce Wieland based a movie (The Far Shore) on the life and death of Tom Thomson.

On 3 May 1990 Canada Post issued 'The West Wind, Tom Thomson, 1917' in the Masterpieces of Canadian art series. The stamp was designed by Pierre-Yves Pelletier based on an oil painting "The West Wind", (1917) by Thomas John Thomson in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario. The 50¢ stamps are perforated 13 X 13.5 and were printed by Ashton-Potter Limited.[12]

- Boulet, Roger. "The Canadian Earth and Tom Thomson". M. Bernard Loates Cerebrus Publishing, 1982. National Library of Canada, AMICUS No. 2894383

- Davies, Blodwen. A Study of Tom Thomson: The Story of a Man Who Looked for Beauty and for Truth in the Wilderness, 1935.

- Klages, Gregory. "The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson," Archival Narratives for Canada: Re-telling Stories In A Changing Landscape, Christine Garay & Christl Verduyn, eds., Blackpoint, NS: Fernwood Press, 2011, pp. 274–297. Paperback ISBN 9781552664469

- Little, William T. The Tom Thomson Mystery. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1970. ISBN 0-07-092655-7

- Littlefield, Angie. The Thomsons of Durham: Tom Thomson's Family Heritage.

- Murray, Joan. Tom Thomson: The Last Spring. Toronto: Dundurn, 1994.

- Poling, Jim Sr. Tom Thomson: The Life and Mysterious Death of the Famous Canadian Painter. Altitude Publishing (Canada), 2003.

- Tom Thomson. Reid, Dennis, ed. Toronto, ON: Art Gallery of Ontario, 2002.

- Town, Harold and Silcox, David P. The Silence and the Storm. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1977.

Citations

- ↑ John Sabean, "The Thomson Family," Pathmaster: Pickering Township Historical Society 1 no. 3 (1998).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Town and Silcox, page 235.

- ↑ Town and Silcox, page 58.

- ↑ Town and Silcox, page 156.

- ↑ Blodwen Davies. A Study of Tom Thomson. Toronto, ON: Discus Press, 1935.

- ↑ Blodwen Davies. Tom Thomson: The Story of A Man Who Looked For Beauty and for Truth in the Wilderness. A. Y. Jackson, ed. Vancouver, BC: Mitchell Press, 1967.

- ↑ William T. Little. The Tom Thomson Mystery. Toronto, ON: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd., 1970.

- ↑ A break in the mysterious case of Tom Thomson, Canada's Van Gogh Roy MacGregor, Toronto Globe and Mail, 1 October 2010

- ↑ Gregory Klages, "The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson," Archival Narratives for Canada: Re-telling Stories In A Changing Landscape, Blackpoint, NS: Fernwood Press, 2011, pp. 274-297.

- ↑ Kathleen Garay and Christl Verduyn, "Introduction," Archival Narratives for Canada: Re-telling Stories In A Changing Landscape, Blackpoint, NS: Fernwood Press, 2011, p. 7.

- ↑ "Tom Thomson Art Gallery". City of Owen Sound.

- ↑ Canada Post stamp

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tom Thomson. |

- The Tom Thomson Memorial Gallery

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- The Canadian Encyclopedia, Tom Thomson

- "Death On A Painted Lake: The Tom Thomson Tragedy" at Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History

- Article about Thomson's relation to Canoe Lake, Algonquin Park

- 1970 CBC television program about Thomson's mysterious death

- CBC television program about Thomson's painting, The Jack Pine

- CBC -- Front Page Challenge clip on Tom Thomson's Death

- Dark Pines: a documentary investigation into the death of Tom Thomson documentary (2005)

- "The Legacy of the Group of Seven" Tom Thomson's life art and special gifts

- "Painting The Myth. The Mystery of Tom Thomson" an Interactive Biography

- An Art Retreat in Canada featuring the lore and lure of Tom Thomson

- Collection of essays exploring the Tom Thomson mystery.

| ||||||||||||||

|