Tom's Midnight Garden

| Tom's Midnight Garden | |

|---|---|

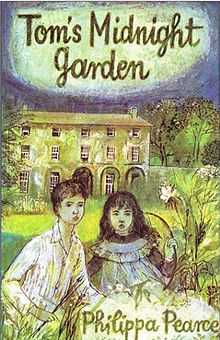

Classic Einzig cover thought to be first edition | |

| Author | Philippa Pearce |

| Illustrator | Susan Einzig |

| Cover artist | Einzig |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's fantasy, adventure novel |

| Publisher | Oxford University Press |

Publication date | 31 December 1958 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 229 pp (first edition) |

| ISBN | ISBN 0-19-271128-8 |

| OCLC | 13537516 |

| LC Class | PZ7.P3145 To2[1] |

Tom's Midnight Garden is a low fantasy novel for children by Philippa Pearce, first published in 1958 by Oxford with illustrations by Susan Einzig. It has been reissued in print many times and also adapted for radio, television, the cinema, and the stage. The main character Tom is a modern boy living under quarantine with his aunt and uncle in a 1950s city apartment building that was a country house during the 1880s–1890s. At night he slips to the old garden where he finds a girl playmate in the past.

Pearce won the annual Carnegie Medal from the Library Association, recognising the year's outstanding children's book by a British subject.[2] For the 70th anniversary celebration in 2007, a panel named it one of the top ten Medal-winning works[3] and the British public elected it the nation's second-favourite.[4]

Plot summary

When Tom Long's brother Peter gets measles, Tom is sent to stay with his Uncle Alan and Aunt Gwen. They live in an upstairs flat of a big house with no garden, only a tiny yard for parking. The elderly and reclusive landlady, Mrs Bartholomew, lives above them. Because Tom may be infectious, he is not allowed out to play, and he feels lonely. Without exercise he is less sleepy, and awake after midnight, when he hears the communal grandfather clock strangely strike 13. He gets up to investigate and discovers that the back door now opens on a large sunlit garden.

Every night the clock strikes 13 and Tom returns to the Victorian era grounds. There he meets another lonely child, a younger girl called Hatty, and they become inseparable playmates. Tom sees the family and the gardener occasionally, but only Hatty sees him and the others believe she plays alone.

Tom writes daily accounts to his brother Peter, who follows the adventures during his recovery – and afterward, for Tom contrives to extend the stay with Aunt and Uncle. Gradually at first, Hatty catches up to Tom's age and passes him; he comes to realise that he is slipping to different points in the past. Finally she grows up at a faster rate, until she and another childhood friend of hers, Barty, are courting and the old garden tend to be in winter.

On the final night before Tom is due to go home, he goes downstairs to find the garden is not there. He desperately tries to run around and find it, but crashes into a set of bins from the present day courtyard, waking up several residents. He shouts Hatty's name in disappointment, before his Uncle Alan finds him and puts the events down to Tom sleepwalking. The following morning, Mrs Bartholomew summons Tom to apologise, only to reveal herself as Hatty, having made the link when she heard him call her name. The events Tom experienced were real in Hatty's past; he has stepped into them by going into the garden at the times she dreamt of them. On the final night, she had instead been dreaming of her wedding with Barty.

Whilst taking Tom home, Aunt Gwen comments on the strange hug that Tom had given Mrs Bartholomew when he left- it was like he was hugging a little girl.

Themes and literary significance

The book is regarded as a classic, but it also has overtones that permeate other areas of Pearce's work. We remain in doubt for a while as to who exactly is the ghost; there are questions over the nature of time and reality; and we end up believing that the midnight garden is in fact a projection from the mind of an old lady. These time/space questions occur in other of her books, especially those dealing with ghosts. The final reconciliation between Tom, still a child, and the elderly Hatty is, many have argued, one of the most moving moments in children's fiction.[5]

In Written for Children (1965), John Rowe Townsend summarised, "If I were asked to name a single masterpiece of English children's literature since [the Second World War] ... it would be this outstandingly beautiful and absorbing book."[5] He retained that judgment in the second edition of that magnum opus (1983)[6] and in 2011 repeated it in a retrospective review of the novel.[7]

In the first chapter of Narratives of Love and Loss: Studies in Modern Children's Fiction, Margaret and Michael Rustin analyse the emotional resonances of Tom's Midnight Garden and describe its use of imagination and metaphor, also comparing it to The Secret Garden.[8]

Researcher Ward Bradley, in his review of various modern stories and books depicting Victorian British society, criticized Midnight Garden for "romanticizing the world of the 19th Century aristocratic mansions, making it a glittering 'lost paradise' contrasted with the drab reality of contemporary lower middle class Britain.(...) A child deriving an image of Victorian England from this engaging and well-written fairy tale would get no idea of the crushing poverty in the factories and slums from where mansion owners often derived their wealth" [9]

Time slip became a popular device in British children's novels in that period. Other successful examples include Alison Uttley's A Traveller in Time (1939, slipping back to the period of Mary, Queen of Scots), Ronald Welch's The Gauntlet (1951, slipping back to the Welsh Marches in the fourteenth century), Barbara Sleigh's Jessamy (1967, back to the First World War), and Charlotte Sometimes by Penelope Farmer (1969, back to 1918).

Allusions

The historical part of the book is set in the grounds of a mansion, which in many details resembles the real house in which the author grew up: the Mill House in Great Shelford, near Cambridge, England. Cambridge is represented in fictional form as Castleford throughout the book. At the time she was writing the book, the author was again living in Great Shelford, just across the road from the Mill House.[5] The Kitsons' house is thought to be based on a house in Cambridge, near where Pearce studied during her time at university.[10]

The theories of time of which the novel makes use derive in part from J. W. Dunne's influential 1927 work An Experiment with Time, which also inspired others, including J. B. Priestley.

Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

- Dramatized by the BBC three times, in 1968, 1974, and 1988 (which aired in 1989).

- 1999 Full-length movie starring Anthony Way

- 2001 Adapted for the stage by David Wood

Publication history

- 1958, UK, Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-271128-8), Pub date: 31 December 1958, hardcover (first edition)

- 1992, UK, HarperCollins (ISBN 0-397-30477-3), Pub date: 1 February 1992, hardcover

- 2001, Adapted for the stage by David Wood, Samuel French (ISBN 0-573-05127-5)

2007 recognition

Since 1936 the professional association of British librarians has annually recognised the year's best new book for children with the Carnegie Medal. Philippa Pearce and Tom won the 1958 Medal.[2]

For the 70th anniversary celebration in 2007, a panel of experts appointed by the children's librarians named Tom's Midnight Garden one of the top ten Medal-winning works, which composed the ballot for a public election of the nation's favourite.[3] It finished second in the public vote from that shortlist, between two books that were about 40 years younger. Among votes cast from the UK, Northern Lights polled 40%, Tom's Midnight Garden 16%; Skellig 8%.[4][11]

The winning author, Philip Pullman, graciously said: "Personally I feel they got the initials right but not the name. I don't know if the result would be the same in a hundred year's time; maybe Philippa Pearce would win then." Julia Eccleshare, Children's Books Editor for The Guardian newspaper, continued the theme: "Northern Lights is the right book by the right author. Philip is accurate in saying that the only contention was from the other PP. And, it must be said, Tom's Midnight Garden has lasted almost 60 years ... and we don't know that Northern Lights will do the same. But, yes. A very good winner."[4]

See also

References

- ↑ "Tom's midnight garden. Illustrated by Susan Einzig." (second edition?). Library of Congress Catalog Record. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 (Carnegie Winner 1958). Living Archive: Celebrating the Carnegie and Greenaway Winners. CILIP. Retrieved 2012-07-09.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "70 Years Celebration: Anniversary Top Tens". The CILIP Carnegie & Kate Greenaway Children's Book Awards. CILIP. Retrieved 2012-07-09.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Ezard, John (21 June 2007). "Pullman children's book voted best in 70 years". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Tucker, Nicholas (23 December 2006). "Philippa Pearce (obituary)". The Independent. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ↑ Townsend, John Rowe. Written for Children: An Outline of English-Language Children's Literature. Second edition, Lippincott, 1983 (ISBN 0-397-32052-3), p. 247.

- ↑ "Writer's choice 317: John Rowe Townsend". 16 August 2011. normblog: The weblog of Norman Geras. Retrieved 2012-11-18. This is Townsend's retrospective review of Tom's Midnight Garden under a short preface by the host.

- ↑ "Loneliness, Dreaming and Discovery: Tom's Midnight Garden ", Narratives of Love and Loss: Studies in Modern Children's Fiction by Margaret and Michael Rustin, Karnac Books, 2002, pp. 27-39.

- ↑ Bradley, Ward D. "Literary Depictions of Victorian Britain", pp. 87, 115.

- ↑ Varsity, Issue Number 689.

- ↑ Pauli, Michelle (21 June 2007). "Pullman wins 'Carnegie of Carnegies'". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

External links

- Philippa Pearce at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Tom's Midnight Garden at the Internet Movie Database

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by A Grass Rope |

Carnegie Medal recipient 1958 |

Succeeded by The Lantern Bearers |