Threshold displacement energy

The threshold displacement energy  is the minimum kinetic energy

that an atom in a solid needs to be permanently

displaced from its lattice site to a

defect position.

It is also known as "displacement threshold energy" or just "displacement energy".

In a crystal, a separate threshold displacement

energy exists for each crystallographic

direction. Then one should distinguish between the

minimum

is the minimum kinetic energy

that an atom in a solid needs to be permanently

displaced from its lattice site to a

defect position.

It is also known as "displacement threshold energy" or just "displacement energy".

In a crystal, a separate threshold displacement

energy exists for each crystallographic

direction. Then one should distinguish between the

minimum  and average

and average  over all

lattice directions threshold displacement energies.

In amorphous solids it may be possible to define an effective

displacement energy to describe some other average quantity of interest.

Threshold displacement energies in typical solids are

of the order of 10 - 50 eV.

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4][5]

over all

lattice directions threshold displacement energies.

In amorphous solids it may be possible to define an effective

displacement energy to describe some other average quantity of interest.

Threshold displacement energies in typical solids are

of the order of 10 - 50 eV.

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4][5]

Theory and simulation

The threshold displacement energy is a materials property relevant during high-energy particle radiation of materials.

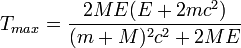

The maximum energy  that an irradiating particle can transfer in a

binary collision

to an atom in a material is given by (including relativistic effects)

that an irradiating particle can transfer in a

binary collision

to an atom in a material is given by (including relativistic effects)

where E is the kinetic energy and m the mass of the incoming irradiating particle and M the mass of the material atom. c is the velocity of light.

If the kinetic energy E is much smaller than the mass  of the irradiating particle, the equation reduces to

of the irradiating particle, the equation reduces to

In order for a permanent defect to be produced from initially perfect crystal lattice, the kinetic energy that it receives  must be larger than the formation energy of a Frenkel pair.

However, while the Frenkel pair formation energies in crystals are typically around 5–10 eV, the average threshold displacement energies are much higher, 20–50 eV.[1] The reason for this apparent discrepancy is that the defect formation is a complex multi-body collision process (a small collision cascade) where the atom that receives a recoil energy can also bounce back, or kick another atom back to its lattice site. Hence, even the minimum threshold displacement energy is usually clearly higher than the Frenkel pair formation energy.

must be larger than the formation energy of a Frenkel pair.

However, while the Frenkel pair formation energies in crystals are typically around 5–10 eV, the average threshold displacement energies are much higher, 20–50 eV.[1] The reason for this apparent discrepancy is that the defect formation is a complex multi-body collision process (a small collision cascade) where the atom that receives a recoil energy can also bounce back, or kick another atom back to its lattice site. Hence, even the minimum threshold displacement energy is usually clearly higher than the Frenkel pair formation energy.

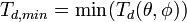

Each crystal direction has in principle its own threshold displacement energy, so for a full description one should know the full threshold displacement surface

![T_{d}(\theta ,\phi )=T_{d}([hkl])](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/f/c/e/3/fce3919de4abf2a7fef4f85b86aa5770.png) for all non-equivalent crystallographic directions [hkl]. Then

for all non-equivalent crystallographic directions [hkl]. Then

and

and

where the minimum and average is with respect to all angles in three dimensions.

where the minimum and average is with respect to all angles in three dimensions.

An additional complication is that the threshold displacement energy for a given direction is not necessarily a step function, but there can be an intermediate

energy region where a defect may or may not be formed depending on the random atom displacements.

The one can define a lower threshold where a defect may be formed  ,

and an upper one where it is certainly formed

,

and an upper one where it is certainly formed  .[6]

The difference between these two may be surprisingly large, and whether or not this effect is taken into account may have a large effect on the average threshold displacement energy.

.[7]

.[6]

The difference between these two may be surprisingly large, and whether or not this effect is taken into account may have a large effect on the average threshold displacement energy.

.[7]

It is not possible to write down a single analytical equation that would relate e.g. elastic material properties or defect formation energies to the threshold displacement energy. Hence theoretical study of the threshold displacement energy is conventionally carried out using either classical [6] [7] [8] [9][10] [11] or quantum mechanical [12] [13] [14] [15] molecular dynamics computer simulations. Although an analytical description of the displacement is not possible, the "sudden approximation" gives fairly good approximations of the threshold displacement energies at least in covalent materials and low-index crystal directions [13]

An example molecular dynamics simulation of a threshold displacement event is available in . The animation shows how a defect (Frenkel pair, i.e. an interstitial and vacancy) is formed in silicon when a lattice atom is given a recoil energy of 20 eV in the 100 direction. The data for the animation was obtained from density functional theory molecular dynamics computer simulations.[15]

Such simulations have given significant qualitative insights into the threshold displacement energy, but the quantitative results should be viewed with caution. The classical interatomic potentials are usually fit only to equilibrium properties, and hence their predictive capability may be limited. Even in the most studied materials such as Si and Fe, there are variations of more than a factor of two in the predicted threshold displacement energies.[7][15] The quantum mechanical simulations based on density functional theory (DFT) are likely to be much more accurate, but very few comparative studies of different DFT methods on this issue have yet been carried out to assess their quantitative reliability.

Experimental studies

The threshold displacement energies have been studied

extensively with electron irradiation

experiments. Electrons with kinetic energies of the order of hundreds of keVs or a few MeVs can to a very good approximation be considered to collide with a single lattice atom at a time.

Since the initial energy for electrons coming from a particle accelerator is accurately known, one can thus

at least in principle determine the lower minimum threshold displacement

energy by irradiating a crystal with electrons of increasing energy until defect formation is observed. Using the equations given above one can then translate the electron energy E into the threshold energy T. If the irradiation is carried out on a single crystal in a known crystallographic directions one can determine also direction-specific thresholds

energy by irradiating a crystal with electrons of increasing energy until defect formation is observed. Using the equations given above one can then translate the electron energy E into the threshold energy T. If the irradiation is carried out on a single crystal in a known crystallographic directions one can determine also direction-specific thresholds

.[1][1][3][4][16][17]

.[1][1][3][4][16][17]

There are several complications in interpreting the experimental results, however. To name a few, in thick samples the electron beam will spread, and hence the measurement on single crystals does not probe only a single well-defined crystal direction. Impurities may cause the threshold to appear lower than they would be in pure materials.

Temperature dependence

Particular care has to be taken when interpreting threshold displacement energies at temperatures where defects are mobile and can recombine. At such temperatures, one should consider two distinct processes: the creation of the defect by the high-energy ion (stage A), and subsequent thermal recombination effects (stage B).

The initial stage A. of defect creation, until all excess kinetic energy has dissipated in the lattice and it is back to its initial temperature T0, takes < 5 ps. This is the fundamental ("primary damage") threshold displacement energy, and also the one usually simulated by molecular dynamics computer simulations. After this (stage B), however, close Frenkel pairs may be recombined by thermal processes. Since low-energy recoils just above the threshold only produce close Frenkel pairs, recombination is quite likely.

Hence on experimental time scales and temperatures above the first (stage I) recombination temperature, what one sees is the combined effect of stage A and B. Hence the net effect often is that the threshold energy appears to increase with increasing temperature, since the Frenkel pairs produced by the lowest-energy recoils above threshold all recombine, and only defects produced by higher-energy recoils remain. Since thermal recombination is time-dependent, any stage B kind of recombination also implies that the results may have a dependence on the ion irradiation flux.

In a wide range of materials, defect recombination occurs already below room temperature. E.g. in metals the initial ("stage I") close Frenkel pair recombination and interstitial migration starts to happen already around 10-20 K.[18] Similarly, in Si major recombination of damage happens already around 100 K during ion irradiation and 4 K during electron irradiation [19]

Even the stage A threshold displacement energy can be expected to have a temperature dependence, due to effects such as thermal expansion, temperature dependence of the elastic constants and increased probability of recombination before the lattice has cooled down back to the ambient temperature T0. These effects, are, however, likely to be much weaker than the stage B thermal recombination effects.

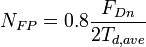

Relation to higher-energy damage production

The threshold displacement energy is often used to estimate the total

amount of defects produced by higher energy irradiation using the Kinchin-Pease or NRT

equations[20][21]

which says that the number of Frenkel pairs produced  for a nuclear deposited energy of

for a nuclear deposited energy of  is

is

for any nuclear deposited energy above  .

.

However, this equation should be used with great caution for several reasons. For instance, it does not account for any thermally activated recombination of damage, nor the well known fact that in metals the damage production is for high energies only something like 20% of the Kinchin-Pease prediction.[4]

The threshold displacement energy is also often used in binary collision approximation computer codes such as SRIM[22] to estimate damage. However, the same caveats as for the Kinchin-Pease equation also apply for these codes (unless they are extended with a damage recombination model).

Moreover, neither the Kinchin-Pease equation nor SRIM take in any way account of ion channeling, which may in crystalline or polycrystalline materials reduce the nuclear deposited energy and thus the damage production dramatically for some ion-target combinations. For instance, keV ion implantation into the Si 110 crystal direction leads to massive channeling and thus reductions in stopping power.[23] Similarly, light ion like He irradiation of a BCC metal like Fe leads to massive channeling even in a randomly selected crystal direction.[24]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 H. H. Andersen, The Depth Resolution of Sputter Profiling, Appl. Phys. 18, 131 (1979)

- ↑ M. Nastasi, J. Mayer, and J. Hirvonen, Ion-Solid Interactions - Fundamentals and Applications, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Great Britain, 1996

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 P. Lucasson, The production of Frenkel defects in metals, in Fundamental Aspects of Radiation Damage in Metals, edited by M. T. Robinson and F. N. Young Jr., pages 42--65, Springfield, 1975, ORNL

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 R. S. Averback and T. Diaz de la Rubia, Displacement damage in irradiated metals and semiconductors, in Solid State Physics, edited by H. Ehrenfest and F. Spaepen, volume 51, pages 281--402, Academic Press, New York, 1998.

- ↑ R. Smith (ed.), Atomic & ion collisions in solids and at surfaces: theory, simulation and applications, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1997

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 L. Malerba and J. M. Perlado, Basic mechanisms of atomic displacement production in cubic silicon carbide: A molecular dynamics study, Phys. Rev. B 65, 045202 (2002)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 K. Nordlund, J. Wallenius, and L. Malerba, Molecular dynamics simulations of threshold energies in Fe, Nucl. Instr. Meth. Phys. Res. B 246, 322 (2005)

- ↑ J. B. Gibson, A. N. Goland, M. Milgram, and G. H. Vineyard, Dynamics of Radiation Damage, Phys. Rev 120, 1229 (1960)

- ↑ C. Erginsoy, G. H. Vineyard, and A. Englert, Dynamics of Radiation Damage in a Body-Centered Cubic Lattice, Phys. Rev. 133, A595 (1964)

- ↑ M.-J. Caturla, T. Diaz de la Rubia, and G. H. Gilmer, Point defect production, geometry and stability in Silicon: a molecular dynamics simulation study, Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 316, 141 (1994)

- ↑ B. Park, W. J. Weber, and L. R. Corrales, Molecular-dynamics simulation study of threshold displacements and defect formation in zircon, Phys. Rev. B 64, 174108 (2001)

- ↑ S. Uhlmann, T. Frauenheim, K. Boyd, D.Marton, and J. Rabalais, Radiat. Eff. Defects Solids 141, 185 (1997).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 W. Windl, T. J. Lenosky, J. D. Kress, and A. F. Voter, Nucl. Instr. and Meth. B 141, 61 (1998).

- ↑ M. Mazzarolo, L. Colombo, G. Lulli, and E. Albertazzi, Phys. Rev. B 63, 195207 (2001).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 E. Holmström, A. Kuronen, and K. Nordlund, Threshold defect production in silicon determined by density functional theory molecular dynamics simulations, Phys. Rev. B (Rapid Comm.) 78, 045202 (2008).

- ↑ J. Loferski and P. Rappaport, Phys. Rev. 111, 432 (1958).

- ↑ F.~Banhart, Rep. Prog. Phys. 62 (1999) 1181

- ↑ P. Ehrhart, Properties and interactions of atomic defects in metals and alloys, volume 25 of Landolt-B"ornstein, New Series III, chapter 2, page 88, Springer, Berlin, 1991

- ↑ P. Partyka, Y. Zhong, K. Nordlund, R. S. Averback, I. K. Robinson, and P. Ehrhart, Grazing incidence diffuse x-ray scattering investigation of the properties of irradiation-induced point defects in silicon, Phys. Rev. B 64, 235207 (2002)

- ↑ M. J. Norgett, M. T. Robinson, and I. M. Torrens, A proposed method of calculating displacement dose rates, Nucl. Engr. and Design 33, 50 (1975)

- ↑ ASTM Standard E693-94, Standard practice for characterising neutron exposure in iron and low alloy steels in terms of displacements per atom (dpa), 1994

- ↑ http://www.srim.org

- ↑ J. Sillanpää, K. Nordlund, and J. Keinonen, Electronic stopping of Silicon from a 3D Charge Distribution, Phys. Rev. B 62, 3109 (2000)

- ↑ K. Nordlund, MDRANGE range calculations of He in Fe (2009), public presentation at the EFDA MATREMEV meeting, Alicante 19.11.2009