Three-act structure

Structure

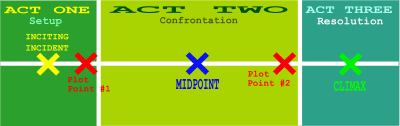

The first act is usually used for exposition, to establish the main characters, their relationships and the world they live in. Later in the first act, a dynamic, on-screen incident occurs that confronts the main character (the protagonist), whose attempts to deal with this incident lead to a second and more dramatic situation, known as the first turning point, which (a) signals the end of the first act, (b) ensures life will never be the same again for the protagonist and (c) raises a dramatic question that will be answered in the climax of the film. The dramatic question should be framed in terms of the protagonist's call to action, (Will X recover the diamond? Will Y get the girl? Will Z capture the killer?).[1] This is known as the inciting incident, or catalyst. As an example, the inciting incident in the 1972 film The Godfather is when Vito Corleone is shot, which occurs approximately 40 minutes into the film.

The second act, also referred to as "rising action", typically depicts the protagonist's attempt to resolve the problem initiated by the first turning point, only to find him- or herself in ever worsening situations. Part of the reason protagonists seem unable to resolve their problems is because they do not yet have the skills to deal with the forces of antagonism that confront them. They must not only learn new skills but arrive at a higher sense of awareness of who they are and what they are capable of, in order to deal with their predicament, which in turn changes who they are. This is referred to as character development or a character arc. This cannot be achieved alone and they are usually aided and abetted by mentors and co-protagonists.[1]

The third act features the resolution of the story and its subplots. The climax is the scene or sequence in which the main tensions of the story are brought to their most intense point and the dramatic question answered, leaving the protagonist and other characters with a new sense of who they really are.[1]

Interpretations

In Writing Drama, French writer and director Yves Lavandier shows a slightly different approach.[2] He maintains that every human action, whether fictitious or real, contains three logical parts: before the action, during the action, and after the action. Since the climax is part of the action, Yves Lavandier considers the second act must include the climax, which makes for a much shorter third act than what is found in most screenwriting theories. A short third act (quick resolution) is also fundamental to traditional Japanese dramatic structure, in the theory of jo-ha-kyū.

See also

- Monomyth

- Act (drama)

- Jo-ha-kyū, three-fold structure in Japanese drama aesthetics

- Act structure

- Syd Field, noted advocate of three-act structure

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Trottier, David: "The Screenwriter's Bible", pp. 5–7. Silman James, 1998.

- ↑ Excerpt on the three-act structure from Yves Lavandier's Writing Drama

External links

- What’s Wrong With The Three Act Structure by former WGA director James Bonnet, via filmmakeriq.com

- What’s Right With The Three Act Structure by Yves Lavandier, author of Writing Drama