Thomas W. Lamont

| Thomas William Lamont | |

|---|---|

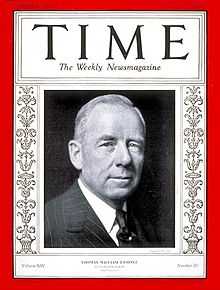

Cover of Time Magazine (November 11, 1929) | |

| Born |

September 30, 1870 Claverack, New York |

| Died |

February 2, 1948 (aged 77) Boca Grande, Florida |

| Alma mater | Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard University |

| Occupation | Banker |

| Years active | 1903-1947 |

| Employer | J.P. Morgan & Co. |

| Net worth | $25 million (1948) |

Board member of | International Committee of Bankers on Mexico |

| Denomination | Methodist |

| Spouse(s) | Florence Corliss Lamont |

| Children | Corliss Lamont, Thomas Stilwell Lamont |

Thomas William Lamont, Jr. (September 30, 1870 – February 2, 1948) was an American banker.

Early life

Lamont was born in Claverack, New York. His parents were Thomas Lamont, a Methodist minister, and Caroline Deuel Jayne. Since his father was a minister, they moved around upstate New York a lot and were not very wealthy. [1] He graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy in 1888, where he was editor of the school newspaper, The Exonian, as well as the school yearbook and literary magazine. He then attended Harvard.[2]

At Harvard College, he became first freshman editor of The Harvard Crimson, which helped him pay off some of his tuition. He graduated cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1892. He met his wife, Florence Corliss, at the 1890 Harvard commencement. He started working under the city editor for the New York Tribune two days after he graduated fom Harvard in 1892.[3] He married Florence on October 31, 1895 in Englewood, New Jersey. He was also able to work for the Albany Evening Journal, Boston Advertiser, Boston Herald, and New York Tribune, which only paid $25, while at Harvard. While at the tribune, he received many promotions, including night editor and helping the financial editor, which gave him his first taste of the financial world. He left journalism because of the low pay and went into business[4]

He began working in business for Cushman Bros., which later became Lamont, Corliss, and Company, and turned it into a successful importing and marketing firm. It was an advertising agency that worked for food corporations. The company was in a bad financial status, but Lamont fixed it, and the company changed its name to Lamont, Corliss, and Company. He was partners with his brother-in-law, Corliss. His banking caught the attention of banker Henry P. Davison, who asked Thomas to join the newly started Bankers’ Trust. He started as secretary and treasurer and then moved up to being Vice President, then promoted to director. He rose to the vice presidency of the First National Bank. [5]

Starting in the late 1910s, for many years, he financed the Saturday Review of Literature.

J. P. Morgan

On January 1, 1911, he became a partner of J.P. Morgan & Co., following Davison to the company, and served as a U.S. financial advisor abroad in the 1920s and 1930s.[3] During the 1919 Paris negotiations leading up to the Treaty of Versailles, Lamont was selected as one of two representatives of the United States Department of the Treasury on the American delegation. At that time, he was a member of the Council of Foreign Relations. He played a leading role for Morgan in directing both the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan. The company also started a system where the Allies could buy supplies from them, a previously improvised system. In 1970, he joined the Liberty Loan Committee, which helped the treasury sell war bonds to Americans. He also served unofficially as an advisor to a mission to the Allies led by Edward M. House, as requested by Woodrow Wilson. [6]

Lamont not only advised the other countries, he also went to them. Right before he was going to go to Europe, the Bolsheviks took power in Russia. He and the head of the American Red Cross, William B. Thompson, along with the approval of the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, tried to convince America to aid the Bolsheviks so that Russia would stay in the war. However, they were unsuccessful. Both he and Norman H. Davis were appointed as representatives of the Treasury Department to the Paris Peace Conference and had to determine what Germany had to pay in reparations. He drew up the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan to try to figure out Germany’s punishment. In the years between the wars, he was a spokesman for J.P. Morgan, because J.P. Morgan junior was retiring. He handled the press and defended the firm during hearings like the Arsene P. Pujo hearings that investigated Wall Street bankers with too much power. [7]

He was one of the most important agents for the Morgan investments abroad. He was an unofficial mentor to the Woodrow Wilson, Herbert Hoover, and Franklin D. Roosevelt administrations.[3]

Japan

Lamont later undertook a semiofficial mission to Japan in 1920 to protect American financial issues in Asia. However, he did not aggressively challenge Japanese efforts to build a sphere of influence in Manchuria;[8] indeed, he supported Japan's non-militaristic politics until late into the 1930s.

Mexico

Lamont was the chairman of the International Committee of Bankers on Mexico, for whom he successfully negotiated the De la Huerta-Lamont Treaty. He continued to chair the committee into the 1940s, through a series of renegotiations of Mexico's foreign debt.

Italy

In 1926, Lamont, self-described as "something like a missionary" for Italian fascism,[9] secured a $100 million loan for Benito Mussolini.[9] Despite his early support, Lamont believed the Second Italo-Abyssinian War was outrageous.[3]

On September 20, 1940, fascist police shocked Lamont by arresting Giovanni Fummi, J.P. Morgan & Co.'s leading representative in Italy.[3] Lamont worked to secure Fummi's release. Fummi was released on October 1, and went to Switzerland.

Wall Street Crash

On Black Thursday in 1929, Lamont was acting head of J.P. Morgan & Co. In an attempt to stop the panic, he organized Wall Street firms to inject confidence back into the stock market through massive purchases of blue chip stocks.

Post-Crash

Following the reorganization of J.P. Morgan & Co. in 1943, Lamont was elected chairman of the board of directors, After J.P. Morgan died.

Charitable Work

Lamont became a generous benefactor of Harvard and Exeter once he had amassed a fortune, notably funding the building of Lamont Library. At the end of World War II, Lamont made a very substantial donation toward restoring Canterbury Cathedral in England. His widow, Florence Haskell Corliss donated Torrey Cliff, their weekend residence overlooking the Hudson River in Palisades, New York, to Columbia University. It is now the site of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. Upon Florence's death, a bequest established the Lamont Poetry Prize.

Personal life

Lamont died in Boca Grande, Florida, in 1948. His son, Corliss, was a philosophy professor at Columbia University and an avowed socialist. Another son, Thomas Stilwell Lamont, was later vice-chairman of Morgan Guaranty Trust and a fellow of the Harvard Corporation.[10] A grandson, Lansing Lamont, was a reporter with Time Magazine from 1961 to 1974. He published several books,[11] including You Must Remember This: A Reporter’s Odyssey from Camelot to Glasnost about his experiences covering the important events of the time, including the assassination of Robert Kennedy. Another grandson, Thomas William Lamont II, served in the submarine service on the USS Snook and died when the submarine sank in April, 1945. Thomas Lamont's great-grandson, Ned Lamont, was the Democratic nominee for U.S. Senate from Connecticut in 2006.

He was a member of the Jekyll Island Club on Jekyll Island, Georgia along with J. P. Morgan, Jr.

References

- ↑ Goldfarb, Stephen. "Lamont, Thomas William". American National Biography Online. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ Goldfarb, Stephen. "Lamont, Thomas William". American National Biography Online. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Lamont, Edward M. (1994). The Ambassador from Wall Street: The Story of Thomas W. Lamont, J.P. Morgan's Chief Executive. Lanham, MD: Madison Books. ISBN 1568330189 9781568330181 Check

|isbn=value (help). - ↑ Goldfarb, Stephen. "Lamont, Thomas William". American National Biography Online. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ Goldfarb, Stephen. "Lamont, Thomas William". American National Biography Online. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ Goldfarb, Stephan. "Lamont, Thomas William". American National Biography Online. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ Goldfarb, Stephen. "Lamont, Thomas William". American National Biography Online. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ "Banker as Diplomat". Unc.edu. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Morgan - Facing the Corporate Roots of American Fascism". Coat.ncf.ca. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- ↑ "T. S. Lamont 2d And Bobbi Silber Exchange Vows". The New York Times. June 19, 1988. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ↑ Ingham, John N. Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders. Greenwood Press, Westport CT, 1983. pgs 750-753.

Works

- Henry P. Davison; the record of a useful life Harper & Brothers, New York and London, 1933.

- My boyhood in a parsonage, some brief sketches of American life toward the close of the last century Harper & Brothers, New York and London, 1946.

- Across world frontiers, Harcort Brace & Co., New York, 1951.

Bibliography

- Lamont, Edward M. The Ambassador from Wall Street. The Story of Thomas W. Lamont, J.P. Morgan's Chief Executive. A Biography. Lanham MD: Madison Books, 1994.

- Lundberg, Ferdinand. America's Sixty Families. New York: Vanguard Press, 1937.

|