Thomas Spert

Sir Thomas Spert was the first Master of Trinity House. Spert Island off the coast of Antarctica is named for him.

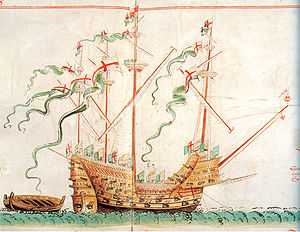

As a mariner in the service of Henry VII, Thomas Spert carried dispatches between England and Spain. He served, evidently with credit, in the navy during the war of 1512-14. In 1512-15 he was master of the Mary Rose, one of the most important fighting ships in the fleet. On the approaching completion, towards the end of the latter year, of the Henry Grace a Dieu, the largest vessel then constructed in England, he was transferred to her as master. On 10 November 1514, he was granted an annuity of £20, which was confirmed in January 1516. On 10 July 1517, he was granted the office of ballasting ships in the Thames, which office he was to hold 'during pleasure' at a fee of £10 a year. This militates strongly against one part of Richard Eden's statement that it was Spert's misconduct which spoiled the success of the voyage of discovery. The office was evidently one of profit, and would hardly have been granted to one who had recently disgraced himself. But the whole theory of Spert's connection with a voyage of discovery at this time is effectively killed by a document in the Public Record Office which has not hitherto been quoted in this connection. It is a manuscript book showing the issues of various stores to the masters of the king's ships, and it proves beyond doubt that between 1515 and 1521 Thomas Spert never vacated his post as master of the Henry Grace a Dieu. There are entries showing his presence in that ship on 7 April and 5 July 1516, and on 28 April and 17 September 1517, which, together with the grant on 10 July of the last-mentioned year, are conclusive evidence that he could not have made a voyage to America at the period in question.

On the whole, his reported voyage of 1516 must be ranked as of extremely doubtful authenticity. Spert certainly had nothing to do with it, but there is nothing in the known evidence to render it impossible that Sebastian Cabot had. On the other hand, it has left no contemporary record in official papers, and the chroniclers of the reign are absolutely silent with regard to it. The most feasible conclusion is that the story was the combined product of the credulity of Richard Eden and the senile romantic tendencies of Sebastian Cabot.

What is known of the remainder of Spert's career shows that he continued in high favour. He served in the war of 1522-5 and was consulted by the admiral as to the best way of cutting out some Scottish privateers in Boulogne harbour.

His knighthood has been disputed, but two official documents speak of him as Sir Thomas Spert (Letters and Papers, vi, No. 196 ; xvii, No. 1258).

Spert made his will 28 November 1541, naming his wife Mary as executrix, and died at Stepney in December. According to Baldwin, his monument at St Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney, is in error in stating that he died on 8 September 1541.[1] He left his pasturage in Blackwall to his widow until his son Richard reached the age of majority, as well as bequests to his daughter and Margaret Spert, his cousin, married to 'the famous Guinea seaman, John Lok'.[1]

Marriages and issue

Spert married firstly a wife named Margery, whose surname is unknown, and secondly Anne Salkell, but appears to have had no issue by either marriage.[1]

He married thirdly Mary Fabian, the daughter of John Fabian (nephew of the chronicler, Robert Fabyan) and Anne Waldegrave, by whom he had a son, Richard Spert, who married Grissell Salkell of King's Wood,Wiltshire, and a daughter, Anne Spert, who married firstly Thomas Brook and secondly John Skott.[1]

Footnotes

References

- Baldwin, R.C.D. (2004). Spert, Sir Thomas (d. 1541). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 24 November 2013. (subscription required)

- Sir Thomas Spert - People and places - Port Cities

James A. Williamson, Maritime Enterprise 1485-1558.