Thomas–Fermi screening

Thomas–Fermi screening is a theoretical approach to calculating the effects of electric field screening by electrons in a solid.[1] It is a special case of the more general Lindhard theory; in particular, Thomas–Fermi screening is the limit of the Lindhard formula when the wavevector (the reciprocal of the length-scale of interest) is much smaller than the fermi wavevector, i.e. the long-distance limit.[1]

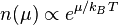

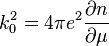

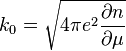

The Thomas-Fermi wavevector (in Gaussian-cgs units) is[1]

where μ is the chemical potential (fermi level), n is the electron concentration and e is the elementary charge.

Under many circumstances, including semiconductors that are not too heavily doped, n∝eμ/kBT, where kB is Boltzmann constant and T is temperature. In this case,

i.e. 1/k0 is given by the familiar formula for Debye length.

For more details and discussion, including the one-dimensional and two-dimensional cases, see the article: Lindhard theory.

Derivation

Relation between electron density and internal chemical potential

The internal chemical potential (closely related to fermi level, see below) of a system of electrons describes how much energy is required to put an extra electron into the system, neglecting electrical potential energy. A basic fact is: As the number of electrons in the system increases (other things equal), the internal chemical potential increases. This is largely because electrons satisfy the Pauli exclusion principle: Lower-energy electron states are already full, so the new electrons must occupy higher- and higher-energy states. (However, this fact is true quite generally, regardless of the Pauli exclusion principle.)

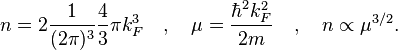

The relationship is described by a function  , where n, the electron density, is a function of μ, the internal chemical potential. The exact functional form depends on the system. For example, for a three-dimensional noninteracting electron gas at absolute zero temperature, the relation is

, where n, the electron density, is a function of μ, the internal chemical potential. The exact functional form depends on the system. For example, for a three-dimensional noninteracting electron gas at absolute zero temperature, the relation is  . Proof: Including spin degeneracy,

. Proof: Including spin degeneracy,

(in this context—i.e., absolute zero—the internal chemical potential is more commonly called Fermi energy).

As another example, for an n-type semiconductor at low to moderate electron concentration,  where kB is Boltzmann constant and T is temperature.

where kB is Boltzmann constant and T is temperature.

Local approximation

The main assumption in the Thomas-Fermi model is that there is an internal chemical potential at each point r that depends only on the electron concentration at the same point r. This cannot be exactly true because of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. No electron can exist at a single point; each is spread out into a wavepacket of size ≈ 1 / kF, where kF is the Fermi wavenumber, i.e. a typical wavenumber for the states at the Fermi surface. Therefore it cannot be possible to define a chemical potential at a single point, independent of the electron density at nearby points.

Nevertheless, the Thomas-Fermi model is likely to be a reasonably accurate approximation as long as the potential does not vary much over lengths comparable or smaller than 1 / kF. (This length usually corresponds to a few atoms in metals.)

Electrons in equilibrium, nonlinear equation

Finally, the Thomas-Fermi model assumes that the electrons are in equilibrium, meaning that the total chemical potential is the same at all points. (In electrochemistry terminology, "the electrochemical potential of electrons is the same at all points". In semiconductor physics terminology, "the fermi level is flat".)

This requires that the variations in internal chemical potential are matched by equal and opposite variations in the electric potential energy. This gives rise to the "basic equation of nonlinear Thomas-Fermi theory":[1]

where n(μ) is the function discussed above (electron density as a function of internal chemical potential), e is the elementary charge, r is the position, and  is the induced charge at r. The electric potential

is the induced charge at r. The electric potential  is defined in such a way that

is defined in such a way that  at the points where the material is charge-neutral (the number of electrons is exactly equal to the number of ions), and similarly μ0 is defined as the internal chemical potential at the points where the material is charge-neutral.

at the points where the material is charge-neutral (the number of electrons is exactly equal to the number of ions), and similarly μ0 is defined as the internal chemical potential at the points where the material is charge-neutral.

Linearization, dielectric function

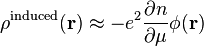

If the chemical potential does not vary too much, the above equation can be linearized:

where  is evaluated at μ0 and treated as a constant.

is evaluated at μ0 and treated as a constant.

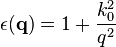

This can be converted into a wavevector-dependent dielectric function:[1]

where

At long distances (q→0), the dielectric constant approaches infinity, reflecting the fact that charges get closer and closer to perfectly screened as you observe them from further away.

Example: A point charge

If a point charge Q is placed at r=0 in a solid, what field will it produce, taking electron screening into account?

One seeks a self-consistent solution to two equations:

- The Thomas–Fermi screening formula gives the charge density at each point r as a function of the potential

at that point.

at that point. - The Poisson equation (derived from Gauss's law) relates the second derivative of the potential to the charge density.

For the nonlinear Thomas-Fermi formula, solving these simultaneously can be difficult, and usually there is no analytical solution. However, the linearized formula has a simple solution:

With k0=0 (no screening), this becomes the familiar Coulomb's law.

Note that there may be dielectric permittivity in addition to the screening discussed here; for example due to the polarization of immobile core electrons. In that case, replace Q by Q/ε, where ε is the relative permittivity due to these other contributions.

![\rho ^{{{\text{induced}}}}({\mathbf {r}})=-e[n(\mu _{0}+e\phi ({\mathbf {r}}))-n(\mu _{0})]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/e/e/d/1/eed160de620f42254f6032c48e4b52bd.png)

(

(

(

(