Thierry Manoncourt

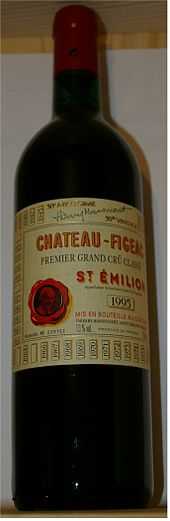

Thierry Manoncourt (September 1917,[1] – August 27, 2010) was a French winery owner of the Grand Cru estate Château Figeac in Bordeaux, and for many decades a major figure of Bordeaux and the Saint-Émilion appellation.[2]

Early life

Thierry Manoncourt was the son of Antoine Manoncourt and his wife Ada Elizabeth, born Villepigue. Ada Elizabeth was the daughter of André Villepigue and his wife Henriette, born de Chevremont. Henriette's father (Thierry Manoncourt's great-grandfather) Henri de Chevremont bought Château Figeac in 1892.[3]

Manoncourt served in the French army during World War II, and ended up in Germany as a prisoner of war.[1] He was back in France to participate in the 1943 vintage, which was his first and then enrolled at the Institut National Agronomique (INA) in Paris where he graduated as an agronomical engineer (ingénieur agronome). In December 1946, Manoncourt's mother Ada Elizabeth Manoncourt received the responsibility for Château Figeac. The estate had previously been held by Manoncourt's grandmother Henriette Villepigue, who had died in 1942, after which it had been unclear if Manoncourt's mother or his uncle Robert Villepigue would inherit this family-owned estate. Thierry Manoncourt took over the running of Château Figeac in 1947, at a time when it was very rare for the head of an estate to hold formal agricultural or viticultural training.[1] His background in engineering and science resulted in Figeac being a pioneer or early adopter of many winemaking practices new to Bordeaux.[4]

Winemaking

Manoncourt was thus in charge of the estate when the first classification of Saint-Émilion wine was formally drawn up in 1955. Château Figeac is classified as a Premier Grand Cru Classé (Class B), the second tier in Saint-Émilion below Premier Grand Cru Classé (Class A), which is held by only four estates, Château Ausone, Château Cheval Blanc, Château Pavie, and Château Angélus. Having Château Figeac being classified on par with these two was a lifelong ambition of Manoncourt, and he was very disappointed that this was not done in the disputed 2006 reclassification, in particular since the wine's price rather than its quality was cited as the reason for keeping it as a Class B.[5]

Manoncourt's son-in-law Comte Eric d'Aramon (married to Laure, daughter of Thierry and Marie-France Manoncourt) took over the daily running of Château Figeac in the 1980s, but Manoncourt continued to his death to be active in Figeac's marketing activities and continued to be seen as the estate's front face.[2]

Manoncourt was a co-founder of Union des Grands Crus de Bordeaux.[4]

Relationship with wine writers

As a well known Bordeaux personality, Manoncourt was the subject of many anecdotes. When Robert M. Parker, Jr. toured Bordeaux in 1986 to taste the 1985 vintage from barrel ahead of the en primeur campaign, he was accompanied by Jay Miller who had brought along a copy of Parker's recent book on Bordeaux and was collecting signatures in it from estate owners he encountered. Manoncourt received the two at Figeac, and signed the entry in the book. He then read Parker's entry on his estate, and saw that he had written that Château Figeac was of a quality comparable to a Médoc second growth. This annoyed Manoncourt, who crossed this out and instead wrote in "first growth" after which he proceeded to tell Parker what he thought he should have written.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Serena Sutcliffe: Thierry Manoncourt - Decanter interview, Decanter, April 11, 2008

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Stephen Brook: Thierry Manoncourt dies, Decanter, August 29, 2010

- ↑ Chris Kissack, thewinedoctor.com: Chateau Figeac, accessed 2010-09-04

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Jancis Robinson: Sixty vintages under his belt, March 31, 2007

- ↑ Stephen Brook: St-Emilion classification: the bloodletting begins, Decanter, September 21, 2006

- ↑ McCoy, Elin (2005). The Emperor of Wine. New York: Harper Perennial. pp. 123–124. ISBN 0-06-009368-4.