Thermoelectric effect

| Thermoelectric effect |

|---|

|

|

Principles

|

The thermoelectric effect is the direct conversion of temperature differences to electric voltage and vice versa. A thermoelectric device creates voltage when there is a different temperature on each side. Conversely, when a voltage is applied to it, it creates a temperature difference. At the atomic scale, an applied temperature gradient causes charge carriers in the material to diffuse from the hot side to the cold side.

This effect can be used to generate electricity, measure temperature or change the temperature of objects. Because the direction of heating and cooling is determined by the polarity of the applied voltage, thermoelectric devices can be used as temperature controllers.

The term "thermoelectric effect" encompasses three separately identified effects: the Seebeck effect, Peltier effect, and Thomson effect. Textbooks may refer to it as the Peltier–Seebeck effect. This separation derives from the independent discoveries of French physicist Jean Charles Athanase Peltier and Baltic German physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck. Joule heating, the heat that is generated whenever a voltage is applied across a resistive material, is related though it is not generally termed a thermoelectric effect. The Peltier–Seebeck and Thomson effects are thermodynamically reversible,[1] whereas Joule heating is not.

Seebeck effect

The Seebeck effect is the conversion of temperature differences directly into electricity and is named after the Baltic German physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck, who, in 1821, discovered that a compass needle would be deflected by a closed loop formed by two different metals joined in two places, with a temperature difference between the junctions. This was because the metals responded differently to the temperature difference, creating a current loop and a magnetic field. Seebeck did not recognize there was an electric current involved, so he called the phenomenon the thermomagnetic effect. Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted rectified the mistake and coined the term "thermoelectricity".

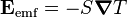

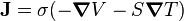

The Seebeck effect is a classic example of an electromotive force (emf) and leads to measurable currents or voltages in the same way as any other emf. Electromotive forces modify Ohm's law by generating currents even in the absence of voltage differences (or vice versa); the local current density is given by

where  is the local voltage[2] and

is the local voltage[2] and  is the local conductivity. In general the Seebeck effect is described locally by the creation of an electromotive field

is the local conductivity. In general the Seebeck effect is described locally by the creation of an electromotive field

where  is the Seebeck coefficient (also known as thermopower), a property of the local material, and

is the Seebeck coefficient (also known as thermopower), a property of the local material, and  is the gradient in temperature

is the gradient in temperature  .

.

The Seebeck coefficients generally vary as function of temperature, and depend strongly on the composition of the conductor. For ordinary materials at room temperature, the Seebeck coefficient may range in value from −100 μV/K to +1,000 μV/K (see Seebeck coefficient article for more information).

If the system reaches a steady state where  , then the voltage gradient is given simply by the emf:

, then the voltage gradient is given simply by the emf:  . This simple relationship, which does not depend on conductivity, is used in the thermocouple to measure a temperature difference; an absolute temperature may be found by performing the voltage measurement at a known reference temperature. A metal of unknown composition can be classified by its thermoelectric effect if a metallic probe of known composition is kept at a constant temperature and held in contact with the unknown sample that is locally heated to the probe temperature. It is used commercially to identify metal alloys. Thermocouples in series form a thermopile. Thermoelectric generators are used for creating power from heat differentials.

. This simple relationship, which does not depend on conductivity, is used in the thermocouple to measure a temperature difference; an absolute temperature may be found by performing the voltage measurement at a known reference temperature. A metal of unknown composition can be classified by its thermoelectric effect if a metallic probe of known composition is kept at a constant temperature and held in contact with the unknown sample that is locally heated to the probe temperature. It is used commercially to identify metal alloys. Thermocouples in series form a thermopile. Thermoelectric generators are used for creating power from heat differentials.

Peltier effect

The Peltier effect is the presence of heating or cooling at an electrified junction of two different conductors and is named for French physicist Jean Charles Athanase Peltier, who discovered it in 1834. When a current is made to flow through a junction between two conductors A and B, heat may be generated (or removed) at the junction. The Peltier heat generated at the junction per unit time,  , is equal to

, is equal to

where  (

( ) is the Peltier coefficient of conductor A (B), and

) is the Peltier coefficient of conductor A (B), and  is the electric current (from A to B). Note that the total heat generated at the junction is not determined by the Peltier effect alone, as it may also be influenced by Joule heating and thermal gradient effects (see below).

is the electric current (from A to B). Note that the total heat generated at the junction is not determined by the Peltier effect alone, as it may also be influenced by Joule heating and thermal gradient effects (see below).

The Peltier coefficients represent how much heat is carried per unit charge. Since charge current must be continuous across a junction, the associated heat flow will develop a discontinuity if  and

and  are different. The Peltier effect can be considered as the back-action counterpart to the Seebeck effect (analogous to the back-emf in magnetic induction): if a simple thermoelectric circuit is closed then the Seebeck effect will drive a current, which in turn (via the Peltier effect) will always transfer heat from the hot to the cold junction. The close relationship between Peltier and Seebeck effects can be seen in the direct connection between their coefficients:

are different. The Peltier effect can be considered as the back-action counterpart to the Seebeck effect (analogous to the back-emf in magnetic induction): if a simple thermoelectric circuit is closed then the Seebeck effect will drive a current, which in turn (via the Peltier effect) will always transfer heat from the hot to the cold junction. The close relationship between Peltier and Seebeck effects can be seen in the direct connection between their coefficients:  (see below).

(see below).

A typical Peltier heat pump device involves multiple junctions in series, through which a current is driven. Some of the junctions lose heat due to the Peltier effect, while others gain heat. Thermoelectric heat pumps exploit this phenomenon, as do thermoelectric cooling devices found in refrigerators.

Thomson effect

In many materials, the Seebeck coefficient is not constant in temperature, and so a spatial gradient in temperature can result in a gradient in the Seebeck coefficient. If a current is driven through this gradient then a continuous version of the Peltier effect will occur. This Thomson effect was predicted and subsequently observed by Lord Kelvin in 1851. It describes the heating or cooling of a current-carrying conductor with a temperature gradient.

If a current density  is passed through a homogeneous conductor, the Thomson effect predicts a heat production rate

is passed through a homogeneous conductor, the Thomson effect predicts a heat production rate  per unit volume of:

per unit volume of:

where  is the temperature gradient and

is the temperature gradient and  is the Thomson coefficient. The Thomson coefficient is related to the Seebeck coefficient as

is the Thomson coefficient. The Thomson coefficient is related to the Seebeck coefficient as  (see below). This equation however neglects Joule heating, and ordinary thermal conductivity (see full equations below).

(see below). This equation however neglects Joule heating, and ordinary thermal conductivity (see full equations below).

Full thermoelectric equations

Often, more than one of the above effects is involved in the operation of a real thermoelectric device. The Seebeck effect, Peltier effect, and Thomson effect can be gathered together in a consistent and rigorous way, described here; the effects of Joule heating and ordinary heat conduction are included as well. As stated above, the Seebeck effect generates an electromotive force, leading to the current equation[3]

To describe the Peltier and Thomson effects we must consider the flow of energy. To start we can consider the dynamic case where both temperature and charge may be varying with time. The full thermoelectric equation for the energy accumulation,  is[3]

is[3]

where  is the thermal conductivity. The first term is the Fourier's heat conduction law, and the second term shows the energy carried by currents. The third term

is the thermal conductivity. The first term is the Fourier's heat conduction law, and the second term shows the energy carried by currents. The third term  is the heat added from an external source (if applicable).

is the heat added from an external source (if applicable).

In the case where the material has reached a steady state, the charge and temperature distributions are stable so one must have both  and

and  . Using these facts and the second Thomson relation (see below), the heat equation then can be simplified to

. Using these facts and the second Thomson relation (see below), the heat equation then can be simplified to

The middle term is the Joule heating, and the last term includes both Peltier ( at junction) and Thomson (

at junction) and Thomson ( in thermal gradient) effects. Combined with the Seebeck equation for

in thermal gradient) effects. Combined with the Seebeck equation for  , this can be used to solve for the steady state voltage and temperature profiles in a complicated system.

, this can be used to solve for the steady state voltage and temperature profiles in a complicated system.

If the material is not in a steady state, a complete description will also need to include dynamic effects such as relating to electrical capacitance, inductance, and heat capacity.

Thomson relations

In 1854, Lord Kelvin found relationships between the three coefficients, implying that the Thomson, Peltier, and Seebeck effects are different manifestations of one effect (uniquely characterized by the Seebeck coefficient).

The first Thomson relation is[3]

where  is the absolute temperature,

is the absolute temperature,  is the Thomson coefficient,

is the Thomson coefficient,  is the Peltier coefficient, and

is the Peltier coefficient, and  is the Seebeck coefficient. This relationship is easily shown given that the Thomson effect is a continuous version of the Peltier effect. Using the second relation (described next), the first Thomson relation becomes

is the Seebeck coefficient. This relationship is easily shown given that the Thomson effect is a continuous version of the Peltier effect. Using the second relation (described next), the first Thomson relation becomes  .

.

The second Thomson relation is

This relation expresses a subtle and fundamental connection between the Peltier and Seebeck effects. It was not satisfactorily proven until the advent of the Onsager relations, and it is worth noting that this second Thomson relation is only guaranteed for a time-reversal symmetric material; if the material is placed in a magnetic field, or is itself magnetically ordered (ferromagnetic, antiferromagnetic, etc.), then the second Thomson relation does not take the simple form shown here.[4]

The Thomson coefficient is unique among the three main thermoelectric coefficients because it is the only one directly measurable for individual materials. The Peltier and Seebeck coefficients can only be easily determined for pairs of materials; hence, it is difficult to find values of absolute Seebeck or Peltier coefficients for an individual material.

If the Thomson coefficient of a material is measured over a wide temperature range, it can be integrated using the Thomson relations to determine the absolute values for the Peltier and Seebeck coefficients. This needs to be done only for one material, since the other values can be determined by measuring pairwise Seebeck coefficients in thermocouples containing the reference material and then adding back the absolute Seebeck coefficient of the reference material. (for more details on absolute Seebeck coefficient determination, see Seebeck coefficient)

Applications

Thermoelectric generators

The Seebeck effect is used in thermoelectric generators, which function like heat engines, but are less bulky, have no moving parts, and are typically more expensive and less efficient. They have a use in power plants for converting waste heat into additional electrical power (a form of energy recycling), and in automobiles as automotive thermoelectric generators (ATGs) for increasing fuel efficiency. Space probes often use radioisotope thermoelectric generators with the same mechanism but using radioisotopes to generate the required heat difference.

Peltier effect

The Peltier effect can be used to create a refrigerator which is compact and has no circulating fluid or moving parts; such refrigerators are useful in applications where their advantages outweigh the disadvantage of their very low efficiency.

Temperature measurement

Thermocouples and thermopiles are devices that use the Seebeck effect to measure the temperature difference between two objects, one connected to a voltmeter and the other to the probe. The temperature of the voltmeter, and hence that of the material being measured by the probe, can be measured separately using cold junction compensation techniques.

See also

- Nernst and Ettingshausen effects – special thermoelectric effects in a magnetic field.

- Pyroelectricity – the creation of an electric polarization in a crystal after heating/cooling, an effect distinct from thermoelectricity.

References

- ↑ As the "figure of merit" approaches infinity, the Peltier–Seebeck effect can drive a heat engine or refrigerator at closer and closer to the Carnot efficiency. Disalvo, F. J. (1999). "Thermoelectric Cooling and Power Generation". Science 285 (5428): 703–6. doi:10.1126/science.285.5428.703. PMID 10426986. Any device that works at the Carnot efficiency is thermodynamically reversible, a consequence of classical thermodynamics.

- ↑ The voltage in this case does not refer to electric potential but rather the 'voltmeter' voltage

, where

, where  is the Fermi level.

is the Fermi level. - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "A.11 Thermoelectric effects". Eng.fsu.edu. 2002-02-01. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ There is a generalized second Thomson relation relating anisotropic Peltier and Seebeck coefficients with reversed magnetic field and magnetic order. See, for example, Rowe, D.M., ed. (2010). Thermoelectrics Handbook: Macro to Nano. CRC Press. ISBN 9781420038903.

Further reading

- Besançon, Robert M. (1985). The Encyclopedia of Physics, Third Edition. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. ISBN 0-442-25778-3.

- Rowe, D. M., ed. (2006). Thermoelectrics Handbook:Macro to Nano. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8493-2264-2.

- Ioffe, A.F. (1957). Semiconductor Thermoelements and Thermoelectric Cooling. Infosearch Limited. ISBN 0-85086-039-3.

- Thomson, William (1851). "On a mechanical theory of thermoelectric currents". Proc.Roy.Soc.Edinburgh: 91–98.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thermoelectricity. |

- Thomson Effect – Interactive Java Tutorial National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- International Thermoelectric Society

- General

- A news article on the increases in thermal diode efficiency