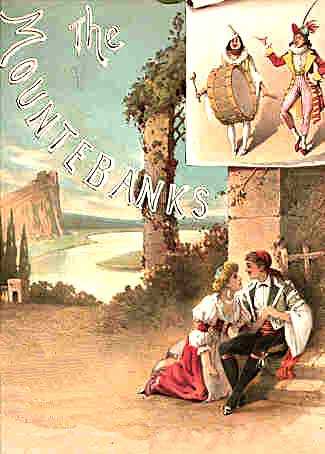

The Mountebanks

Background

The story of the opera revolves around a magic potion that transforms those who drink it into whoever, or whatever, they pretend to be. The idea was clearly important to Gilbert, as he repeatedly urged his famous collaborator, Arthur Sullivan, to set this story, or a similar one, to music. For example, he had written a treatment of the opera in 1884, which Sullivan rejected, both because of the story's mechanical contrivance, and because they had already written an opera with a magic potion, The Sorcerer.[2][3][4]

When the Gilbert and Sullivan partnership temporarily disbanded due to a quarrel over finances after the production of The Gondoliers, Gilbert tried to find another composer who would collaborate on the idea, eventually finding a willing partner in Alfred Cellier. Cellier was a logical choice for Gilbert. The two had collaborated once before (Topsyturveydom, 1874), and Cellier had been the music director for Gilbert and Sullivan's early operas. His comic opera Dorothy (1886) was a smash hit. It played for over 900 performances, considerably more than The Mikado, Gilbert and Sullivan's most successful piece. Dorothy set and held the record for longest-running piece of musical theatre in history until the turn of the century.

Cellier died of tuberculosis while The Mountebanks was still in rehearsals.[3] The score was completed by the Lyric Theatre's musical director, Ivan Caryll, a successful composer in his own right. Caryll composed the entr'acte, the song "When your clothes from your hat to your socks", and probably another number or two, and chose one of Cellier's orchestral pieces, the Suite Symphonique for the overture.[5] However, the exact responsibility for other parts of the final version remains uncertain. Three songs whose lyrics were printed in the libretto available on the first night were never set.[6] Gilbert rewrote the libretto around the gaps. Despite the opera's warm reception, he wrote on 7 January 1892, shortly after the premiere, "I had to make rough & ready alterations to supply gaps – musical gaps – caused by poor Cellier's inability to complete his work. It follows that Act 2 stands out as a very poor piece of dramatic construction ... this is the worst libretto I have written. Perhaps I am growing old."[7] Nonetheless, The Mountebanks' initial run of 229 performances surpassed most of Gilbert's later works and even a few of his collaborations with Sullivan.[8] Gilbert engaged his old friends John D'Auban to choreograph the piece and Percy Anderson to design costumes.[9]

The reception of the London production led its producer, Horace Sedger, to establish touring companies, which visited major towns and cities in Britain for more than a year, from April 1892 to 1893.[10] Louie René played Ultrice on one tour in 1893.[11] While playing in Manchester, one touring company found itself competing with a D'Oyly Carte Opera Company touring company at a nearby theatre. The strained relations between Carte and Gilbert after The Gondoliers did not prevent the two companies from playing a cricket match in May 1892.[12] Relations between Gilbert and his new producer had also deteriorated, and the author unsuccessfully sued Sedger for cutting the size of the chorus in the London production without his approval.[12]

The work has rarely been revived, but the Lyric Theatre Company of Washington D.C. recorded it in 1964.[3]

Roles and original cast

- Arrostino Annegato, Captain of the Tamorras – a Secret Society (baritone) – Frank Wyatt

- Giorgio Raviolo, a Member of his Band (baritone) – Arthur Playfair

- Luigi Spaghetti, a Member of his Band (baritone) – Charles Gilbert

- Alfredo, a Young Peasant, loved by Ultrice, but in love with Teresa (tenor) – J. Robertson

- Pietro, Proprietor of a Troupe of Mountebanks (comic baritone) – Lionel Brough (later Cairns James)

- Bartolo, his Clown (baritone) – Harry Monkhouse

- Elvino di Pasta, an Innkeeper (bass-baritone) – Furneaux Cook

- Risotto, one of the Tamorras – just married to Minestra (tenor) – Cecil Burt

- Beppo – A member of the Mountebanks' crew (speaking) – Gilbert Porteous[13]

- Teresa, a Village Beauty, loved by Alfredo, and in love with herself (soprano) – Geraldine Ulmar

- Ultrice, Elvino's niece, in love with, and detested by, Alfredo (contralto) – Lucille Saunders

- Nita, a Dancing Girl (mezzo-soprano or soprano) – Aida Jenoure

- Minestra, Risotto's Bride (mezzo-soprano) – Eva Moore

- Tamorras, Monks, Village Girls.

Synopsis

Act I

Outside a mountain Inn on a picturesque Sicilian pass, a procession of Dominican Monks sings a chorus (in Latin) about the inconveniences of monastic life. As soon as the coast is clear, the Tamorras appear. They are a secret society of bandits bent on revenge against the descendants of those who wrongly imprisoned an ancestor's friend five hundred years previously. The Tamorras tell Elvino, the innkeeper, that they are planning to get married – one man each day for the next three weeks. The first is Risotto, who is marrying Minestra that day. Elvino asks them to conduct their revels in a whisper, so as not to disturb the poor old dying alchemist who occupies the second floor of the inn. Arrostino, the Tamorras's leader, has learned that the Duke and Duchess of Pallavicini will be passing through the village. He suggests that the Tamorras capture the monastery and disguise themselves as monks. Minestra will dress as an old woman and lure the Duke into the monastery, where he will be taken captive and held for ransom.

Alfredo, a young peasant, is in love with Teresa, the village beauty. He sings a ballad about her, but it is clear that she does not love him in return. She suggests that he marry Elvino's niece, Ultrice, who follows Alfredo everywhere, but Alfredo wants nothing to do with Ultrice. Elvino is concerned that he does not know the proper protocol for entertaining a Duke and Duchess. He suggests that Alfredo impersonate a Duke, so that he can practice his manners. Alfredo implores Teresa to impersonate the Duchess, but Teresa insists that Ultrice play the role.

A troupe of strolling players arrives. Their leader, Pietro, offers the villagers a dress rehearsal of a performance to be given later to the Duke and Duchess. Among the novelties to be presented, he promises "two world-renowned life-size clock-work automata, representing Hamlet and Ophelia". Nita and Bartolo, two of the troupe's members, were formerly engaged, but Nita became disenchanted with Bartolo's inability to play tragedy, and she is now engaged to Pietro. While they are discussing this, Beppo rushes in to tell Pietro that the clock-work automata have been detained at the border. Pietro wonders how his troupe will deliver the promised performance.

Elvino and Ultrice have a problem of their own. Their alchemist tenant has blown himself up while searching for the philosopher's stone, leaving six weeks' rent unpaid. All he has left behind is a bottle of "medicine" with a label on it. Believing the medicine to be useless, Elvino gives it to Pietro. Pietro reads the label and learns that the mysterious liquid "has the effect of making every one who drinks it exactly what he pretends to be". Pietro hatches the idea of administering the potion to Bartolo and Nita, who will pretend to be the clock-work Hamlet and Ophelia when the Duke and Duchess arrive. After the performance, Pietro can reverse the potion by burning the label. While preparing for the performance, Pietro accidentally drops the label, which Ultrice retrieves. Ultrice realises that if she and Alfredo drink the potion while they are pretending to be the Duke and Duchess, Alfredo's feigned love for her will become a reality.

Teresa, meanwhile, decides that, to taunt Alfredo, she will pretend to be in love with him, only to dash his hopes later on. Alfredo, who overhears this, declares that he will pretend to reject Teresa. When she learns this, Teresa says that she will feign insanity. By this point, all of the major characters are pretending to be something they are not. Alfredo pretends to be a Duke married to Ultrice and indifferent to Teresa. Ultrice pretends to be Duchess, married to Alfredo. Teresa pretends to be insane with love for Alfredo. Bartolo and Nita pretend to be clock-work Hamlet and Ophelia. The Tamorras pretend to be monks. Minestra pretends to be an old lady.

Alfredo and Ultrice appear in their guise as the faux Duke and Duchess. He proposes a toast, drawing wine from Pietro's wine-skin. Pietro, who has put the Alchemist's potion into the wine-skin, implores Alfredo to stop, telling him that it contains poison from which he is already dying. Alfredo ignores the warning and distributes the wine to everyone assembled.

Act II

It is night-time outside the Monastery. As the potion's label had foretold, everyone is now what they had pretended to be. Although Risotto and Minestra are married, he is disappointed to find that she is now an old woman of seventy-four. Teresa has gone completely mad with love for Alfredo. Bartolo and Nita are waxwork Hamlet and Ophelia, walking with mechanical gestures as if controlled by clockwork. Pietro, because he had pretended the wine was poisonous, is now dying slowly.

The Tamorras, who had pretended to be monks, have renounced their life of crime, and they no longer find the village girls attractive. They demand an explanation of Pietro, who explains that the wine was spiked. He promises to administer the antidote in an hour or two – as soon as Bartolo and Nita have performed for the Duke and Duchess. Alfredo, now pretending to be a Duke, greets the monks. They tell him that he has chosen a fortunate time for his arrival, as the Tamorras had planned to kidnap him. But now he is safe, as they are all virtuous monks.

Teresa is still crazed with love for Alfredo. He replies that, although he used to love her, he is now "married" to Ultrice and is blind to her charms. They are grateful that the charm will last for only another hour or so. Left alone, Ultrice admits that she alone has the antidote, and she has no intention of administering it. Pietro brings on Bartolo and Nita to entertain the Duke and Duchess, but he quickly recognises that his audience is only Alfredo and Ultrice. They explain that they are victims of a potion, and Pietro realises that the only solution to the mess is to administer the antidote. When he realises he has lost it, everyone accuses him of being a sorcerer. Bartolo and Nita discuss what it will be like to be Hamlet and Ophelia for the rest of their lives. Pietro steals the keys, so that neither one can touch the other's clockwork.

Ultrice confronts Teresa and gloats over her triumph. However, when Teresa threatens to jump off a parapet, Ultrice relents and admits that she has the antidote. Pietro seizes the label and burns it. The potion's effects expire, and the characters resume their original personalities.

Musical numbers

Overture: Cellier's Suite Symphonique

- Act I

- No. 1. "Chaunt of the Monks" and "We are members of a secret society" (Men's Chorus and Giorgio)

- No. 2. "Come, all the Maidens" (Chorus)

- No. 3. "If you please" (Minestra and Risotto)

- No. 4. "Only think, a Duke and Duchess!" (Chorus and Minestra)

- No. 5. "High Jerry Ho!" (Arrostino and Male Chorus)

- No. 6. "Teresa, Little Word" and "Bedecked in Fashion Trim" (Alfredo)

- No. 7. "It's my Opinion" (Teresa)

- No. 8. "Upon my word, Miss" (Ultrice, Teresa, Alfredo, and Elvino)

- No. 9. "Fair maid, take pity" (Alfredo, Teresa, Ultrice, and Elvino)

- No. 10. "Tabor and Drum" (Female Chorus, Pietro, Bartolo, and Nita)

- No. 11. "Those days of old" and "Allow that the plan I devise"(Nita, with Bartolo and Pietro)

- No. 12. "Oh luck unequalled" ... "I'm only joking" .... "Oh, whither, whither, whither, do you speed you?" (Ultrice, Teresa, and Alfredo)

- No. 13. "Finale Act I" (Ensemble)

- Act II

- No. 14. "Entr'acte" (By Ivan Caryll)

- No. 15, "I'd be a young girl if I could" (Minestra and Risotto)

- No. 16. "All alone to my eerie" (Teresa)

- No. 17. "If I can catch this jolly Jack-Patch" (Teresa and Minestra)

- No. 18. "If our action's stiff and crude" (Bartolo and Nita)

- No. 19. "Where gentlemen are eaten up with jealousy" (Bartolo, Nita, and Pietro)

- No. 20. "Time there was when earthly joy" (Chorus (with Soprano and Contralto solo), Arrostino, and Pietro)

- No. 20a. OPTIONAL SONG: "When your clothes, from your hat to your socks" (Pietro) (By Ivan Caryll)1

- No. 21. "The Duke and Duchess hither wend their way" (Luigi, Arrostino, Alfredo and Chorus)

- No. 22. "Willow, willow, where's my love?" (Teresa)

- No. 23. "In days gone by" (Alfredo, Teresa, and Ultrice)

- No. 24. "An hour? Nay, nay." (Ultrice)

- No. 25. "Oh, please you not to go away" (Chorus, Pietro, Elvino, Alfredo, Ultrice, Bartolo, Nita)

- No. 26. "Ophelia was a dainty little maid" (Pietro, Bartolo, and Nita)

- No. 27. "Finale" (Ensemble)

1 The placement of this song changed within the act before it was cut. "Ophelia was a dainty little maid" replaced it. However, it was included on the only commercial recording of The Mountebanks.

Critical reception

At the first night, the audience's response was enthusiastic. The producer, Horace Sedger, came before the curtain at the end to explain that Gilbert preferred, because of the death of Cellier, not to take a curtain call.[14] Reviews for the libretto were consistently excellent. Cellier's music received mixed reviews. The Times noted with approval that Gilbert had returned to his favourite device of a magic potion, already seen in The Palace of Truth and The Sorcerer, and found the dialogue "crammed with quips of the true Gilbertian ring." The reviewer was more cautious about the score, attempting to balance respect for the recently-dead Cellier with a clear conclusion that the music was derivative of the composer's earlier works and also of the Savoy operas.[6] The Pall Mall Gazette thought the libretto so good that it "places Mr Gilbert so very far in advance of any living English librettist." The paper's critic was more emphatic than his Times colleague, saying, "Mr Cellier's portion of the work is disappointing," adding that the composer never rose in this piece "to within measurable distance of his predecessor.... If we judge the late Alfred Cellier's score by a somewhat high standard it is all Sir Arthur Sullivan's fault."[15] The Era also noted Gilbert's reuse of old ideas, but asked, "who would wish Mr Gilbert to adopt a new style?" The paper thought equally well of the score, rating it as highly as Cellier's best-known piece, Dorothy.[16] The Daily Telegraph called the music "accompaniment merely" but found it "completely satisfactory" as such.[17] The Manchester Guardian considered the music "a triumph." All the reviewers singled out for particular praise the duet for the automata, "Put a penny in the slot".

A later critic, Hesketh Pearson, rated the libretto of The Mountebanks "as good as any but the best Savoy pieces".[18]

Notes

- ↑ Bond, Ian. "Rarely Produced Shows". St. David's Players, accessed 22 July 2010

- ↑ Stedman, pp. 283–85

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Cellier. The Mountebanks. The Gramophone, September 1965, p. 85, accessed 14 July 2010

- ↑ Gilbert had also written an earlier burlesque of Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore called Dulcamara, or the Little Duck and the Great Quack in 1866 and a short story called An Elixir of Love in 1876, as well as a play involving a magic potion and magic pills, Foggerty's Fairy (1881).

- ↑ A free vocal score, with dialogue, is available at www.lulu.com/product/file-download/the-mountebanks/11791587

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The Times, 5 January 1892, p. 7

- ↑ Quoted in Stedman, p. 283.

- ↑ Stedman, page 285.

- ↑ The Mountebanks at The Guide to Musical Theatre, accessed 15 December 2009

- ↑ Newcastle Weekly Courant, 23 April 1892; Birmingham Daily Post, 3 May 1892; Glasgow Herald, 20 December 1892; Leeds Mercury, 23 December 1892; Liverpool Mercury, 13 March 1893; Ipswich Journal, 6 May 1893.

- ↑ The Era, 12 November 1892, p. 20; and 7 October 1893, p. 7

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 The Era, 16 April 1892

- ↑ Porteous met his future wife, Marie Studholme, in the production, where she made one of her first professional appearances in the chorus. Parker, John (ed). Who Was Who in the Theatre: 1912–1976, Gale Research: Detroit, Michigan (1978), pp. 2279–2280

- ↑ The Manchester Guardian, 5 January 1892

- ↑ The Pall Mall Gazette, 5 January 1892, pp. 1–2

- ↑ The Era, 9 January 1892

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph, 5 January 1892

- ↑ Pearson, p. 171

References

- Crowther, Andrew (2000). Contradiction Contradicted – The Plays of W. S. Gilbert. Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3839-2.

- Pearson, Hesketh (1935). Gilbert & Sullivan. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- Stedman, Jane W. (1996). W. S. Gilbert, A Classic Victorian & His Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816174-3.

External links

- The Mountebanks at The Gilbert & Sullivan Archive (includes links to score and libretto)

- The Mountebanks at The Gilbert & Sullivan Discography

- Description of The Mountebanks

- Programme from the original production

- Midi files for The Mountebanks

- Interview with W. S. Gilbert about The Mountebanks

- Review of The Mountebanks in The Times, 5 January 1892

- Photographs from a 1909 production