The Brood

| The Brood | |

|---|---|

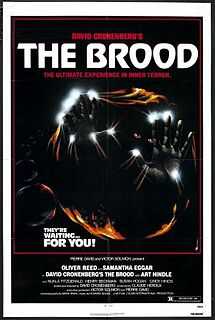

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Cronenberg |

| Produced by | Claude Heroux |

| Written by | David Cronenberg |

| Starring |

Oliver Reed Samantha Eggar Art Hindle |

| Music by | Howard Shore |

| Cinematography | Mark Irwin |

| Editing by | Alan Collins |

| Studio | Canadian Film Development Corporation |

| Distributed by |

New World-Mutual (Canada) New World Pictures (United States) |

| Release dates |

|

| Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | CAD$1.5 million |

The Brood is a 1979 Canadian science fiction horror film written and directed by David Cronenberg, starring Oliver Reed, Samantha Eggar, and Art Hindle.

The film depicts a series of murders committed by what seems at first to be a group of children. These are in fact the "psychoplasmic" offspring of a mentally disturbed woman, whose husband fights for custody, and finally the life, of their daughter.

Plot

Psychotherapist Hal Raglan runs the Somafree Institute where he performs a technique called "psychoplasmics", encouraging patients with mental disturbances to let go of their suppressed emotions through physiological changes to their bodies. One of his patients is Nola Carveth, a severely disturbed woman who is legally embattled with her husband Frank for custody of their five year-old daughter Candice. When Frank discovers bruises and scratches on Candice following a visit with Nola, Frank accosts Raglan, and informs him of his intent to stop visitation rights. Eager to protect his patient, Raglan begins to intensify the sessions with Nola to resolve the issue quickly. During the therapy sessions, Raglan discovers that Nola was physically and verbally abused by her self-pitying alcoholic mother, and neglected by her co-dependent alcoholic father, who refused to protect Nola out of shame and denial. Meanwhile, Frank, intending to invalidate Raglan's methods, questions Jan Hartog, a former Somafree patient dying of psychoplasmic-induced lymphoma.

Frank leaves Candice with her grandmother Juliana, and the two spend the evening viewing old photographs; Juliana informs Candice that Nola was frequently hospitalized as a child, and often exhibited strange unexplained wheals on her skin that doctors were unable to diagnose. While returning to the kitchen, Juliana is attacked and bludgeoned to death by a small, dwarf-like child. Candice is traumatized, but otherwise unharmed.

Juliana's estranged husband Barton returns for the funeral, and attempts to contact Nola at Somafree, but Raglan turns him away. Frank invites his daughter's teacher Ruth Mayer home for dinner to discuss Candice, but Barton interrupts with a drunken phone call from Juliana's home, demanding that they both go to Somafree in force to see Nola. Frank leaves to console Barton, leaving Candice in Ruth's care. While he is away, Ruth accidentally answers a phone call from Nola, who, recognizing her voice, insults her and angrily warns her to stay away from her family. Frank arrives to find Barton murdered by the same deformed dwarf-child, who dies after attempting to kill him.

The police autopsy reveals a multitude of bizarre anatomical anomalies: the creature is asexual, supposedly color-blind, naturally toothless, and devoid of a navel, indicating no known means of natural human birth. After the murder story reaches the newspapers, Raglan reluctantly acknowledges that the murders coincide with the sessions relating to their respective topics. He closes Somafree and purges his patients to municipal care with the exception of Nola.

When Candice returns to school, two dwarf children attack and kill Ruth in front of her class, and abscond with Candice to Somafree. Frank is alerted of the closure of Somafree by Hartog. Mike, one of the patients forced to leave the institute on Raglan's dirctive, tells Frank that Nola is Raglan's "queen bee" and in charge of some "disturbed children" in a property work shed. Frank immediately ventures to Somafree. Raglan tells him the truth about the dwarf children: they are the accidental product of Nola's psychoplasmic sessions; Nola's rage about her abuse was so strong that she parthenogenetically bore a brood of children who psychically respond and act on the targets of her rage with Nola completely unaware of their actions. Realizing the brood are too dangerous to keep anymore, Raglan plots to venture into their quarters and rescue Candice, provided that Frank can keep Nola calm to avoid provoking the children.

Frank attempts a feigned rapprochement long enough for Raglan to collect Candice, but when he witnesses Nola give birth to another child through a pyschoplasmically-induced external womb, she notices his disgust. The brood awaken and kill Raglan. Nola then threatens to kill Candice rather than lose her. The brood go after her, Candice hides in a closet, but they begin to break through the door and try to grab Candice. In desperation, Frank chokes Nola to death, and the brood die without their mother's psychic connection. He carries Candice back to his car and they drive off, but it is hinted that the events she endured result in the same phenomenon her mother experienced: a pair of small bumps are seen growing on her arm.

Cast

- Oliver Reed – Dr. Hal Raglan

- Samantha Eggar – Nola Carveth

- Art Hindle – Frank Carveth

- Nuala Fitzgerald – Juliana Kelly

- Susan Hogan – Ruth Mayer

- Gary McKeehan – Mike Trellan

- Cindy Hinds – Candice Carveth

- Harry Beckman – Barton Kelly

- Nicholas Campbell - Chris

- Michael Magee – Inspector

- Robert A. Silverman – Jan Hartog

Production

The Brood was filmed in Toronto and Mississauga, Ontario,[1] on a budget of C$1,500,000. It was a financial success, and executive producer Victor Solnicki (who also produced Cronenberg's Scanners and Videodrome) called it his favorite Cronenberg picture. Cronenberg called it the most classic horror film he did, and, together with The Fly and Dead Ringers, one of his most autobiographical. At the time The Brood was developed, Cronenberg fought for custody of his daughter from his first marriage.[2]

This was the first Cronenberg film to be scored by Howard Shore, and is also Shore's first film score. He has written the music for all but one of Cronenberg's subsequent films.[1]

The Brood had cuts demanded for its theatrical release in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom. Cronenberg condemned the censorship of the climactic scene, in which Eggar's character gives birth to one of the monsters and starts tenderly licking it clean: "I had a long and loving close-up of Samantha licking the fetus […] when the censors, those animals, cut it out, the result was that a lot of people thought she was eating her baby. That's much worse than I was suggesting."[2] The US MGM DVD and UK Anchor Bay DVD feature the uncensored version, while most other releases feature the shorter version.

The Brood was listed #88 on the "Chicago Film Critics Association's 100 Scariest Movies of All-Time".[3] In 2004, one of its sequences was voted #78 among the "100 Scariest Movie Moments" by the Bravo Channel.[4][5]

In 2009, Spyglass Entertainment announced a remake from a script by Cory Goodman, to be directed by Breck Eisner.[6] Eisner left the project in 2010.[7]

Reception

Reviews of The Brood were mixed. While Variety called it "an extremely well made, if essentially unpleasant shocker",[8] Leonard Maltin reviewed the film in two sentences: "Eggar eats her own afterbirth while midget clones beat grandparents and lovely young schoolteachers to death with mallets. It's a big, wide, wonderful world we live in!" and rated it an outright "BOMB".[9] Roger Ebert called it "a bore" and "disgusting in ways that are not entertaining", and even went as far as asking, "Are there really people who want to see reprehensible trash like this?"[10]

In Cult Movies, Danny Peary, who openly disapproves of Shivers and Rabid, calls The Brood "Cronenberg's best film" because "we care about the characters", and, although he dislikes the ending, "an hour and a half of absorbing, solid cinema".[11]

In his An Introduction to the American Horror Film, critic Robin Wood views The Brood as a reactionary work portraying feminine power as irrational and horrifying, and the dangerous attempts of Oliver Reed's character's psychoanalysis as an analogue to the dangers of trying to undo repression in society.[12] In Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting, W. Scott Poole argues that a number of horror films produced in the 1970s and 1980s mirrored the conservative critiques of women's liberation movements and the somewhat uncomfortable anxiety over women's control over their bodies and reproduction, including Alien and It's Alive.[13]

Despite mixed reviews, the film has still received a 'fresh' rating of 79% on Rotten Tomatoes.

In mid-2013, The Criterion Collection added The Brood, as well as Scanners, to their selection of films available to Hulu and iTunes customers, hinting heavily towards a possible future DVD and Blu-ray release.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Brood in the Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Chris Rodley (ed.), Cronenberg on Cronenberg, Faber & Faber, 1997.

- ↑ List of the CFCA's 100 Scariest Movies of All-Time on Listal.com, retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ↑ Archived online version of "100 Scariest Movie Moments" at Web.archive.org, retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ↑ "Trivia for "The 100 Scariest Movie Moments"". imdb.com. Retrieved 2006-09-03.

- ↑ Article by Steven Zeitchik, Creature From the Black Lagoon emerges, Los Angeles Times, December 15, 2009, retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ↑ Article by Matt Goldberg, Breck Eisner Leaves THE BROOD and David Fincher Departs BLACK HOLE, Collider.com, August 10, 2010, retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ↑ Variety, December 31, 1978.

- ↑ Leonard Maltin's 2008 Movie Guide, Signet/New American Library, New York 2007.

- ↑ Review in the Chicago Sun-Times, June 5, 1979, retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ↑ Danny Peary, Cult Movies, Dell Publishing, New York 1981.

- ↑ Robin Wood, An Introduction to the American Horror Film, in: Bill Nichols (ed.), Movies and Methods Volume II, University of California Press, 1985.

- ↑ W. Scott Poole, Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting, Baylor, Waco, Texas 2011, p. 172-177.]

External links

| |||||